Introduction: The Black Box of Academic Publishing

If you are a student or researcher, you likely know the anxiety that comes after clicking the “Submit” button on a conference paper. For the next few months, your work enters a “black box.” Inside, anonymous reviewers judge your methods, debate your findings, and ultimately decide the fate of your research.

Peer review is the cornerstone of scientific integrity, yet it is notoriously fraught with challenges. It suffers from high variance (the “luck of the draw” with reviewers), potential biases against novice authors, and the opaque motives of the reviewers themselves. We know these problems exist, but studying them scientifically is incredibly difficult. Privacy concerns prevent us from seeing who reviewed what, and the sheer number of variables—from the reviewer’s mood to the Area Chair’s leadership style—makes it nearly impossible to isolate specific causes for a rejection.

What if we could simulate the entire process? What if we could create thousands of “synthetic” peer reviews using AI, tweaking variables to see exactly how a “lazy” reviewer or a “biased” Area Chair changes the outcome?

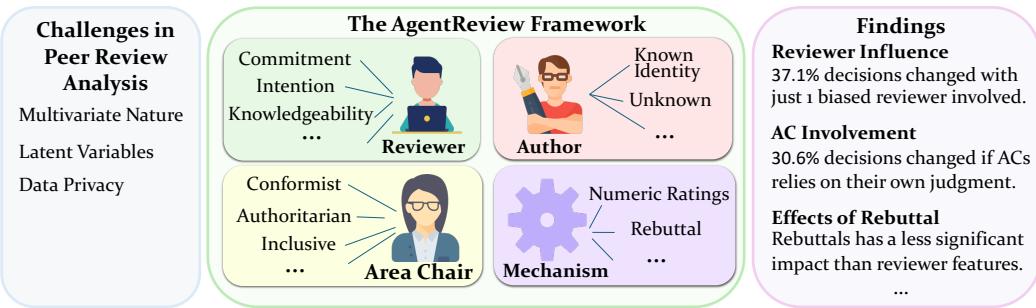

This is exactly what the authors of AGENTREVIEW have done. By leveraging Large Language Models (LLMs), they built a comprehensive framework to simulate peer review dynamics. Their work offers a fascinating, quantitative look into the sociology of science, uncovering how conformity, fatigue, and authority bias can dramatically skew the results of academic publishing.

Background: Why Simulate Peer Review?

Traditional studies of peer review rely on post-hoc analysis. Researchers look at data after a conference is over to find patterns. While useful, this approach has limits. You cannot re-run a conference to see if a paper would have been accepted if “Reviewer 2” had been less grumpy. You cannot easily disentangle the quality of the paper from the bias of the reviewer.

The AGENTREVIEW framework proposes a different approach: Agent-Based Modeling (ABM). In this setup, LLMs (specifically GPT-4) act as the participants in the review process. Because LLMs have demonstrated an impressive ability to understand academic text and simulate specific personas, they can be “cast” in different roles.

This simulation allows for controlled experiments. The researchers can take a real paper from a past conference (like ICLR) and feed it into the system, but change the “personalities” of the AI reviewers. This isolates variables in a way that is impossible in the real world, preserving privacy while generating statistically significant data.

The Core Method: Inside the AGENTREVIEW Machine

The AGENTREVIEW framework is designed to mirror the standard pipeline of top-tier Machine Learning and NLP conferences. It isn’t just about generating a summary; it simulates the social interactions and phases that define a real review cycle.

The 5-Phase Pipeline

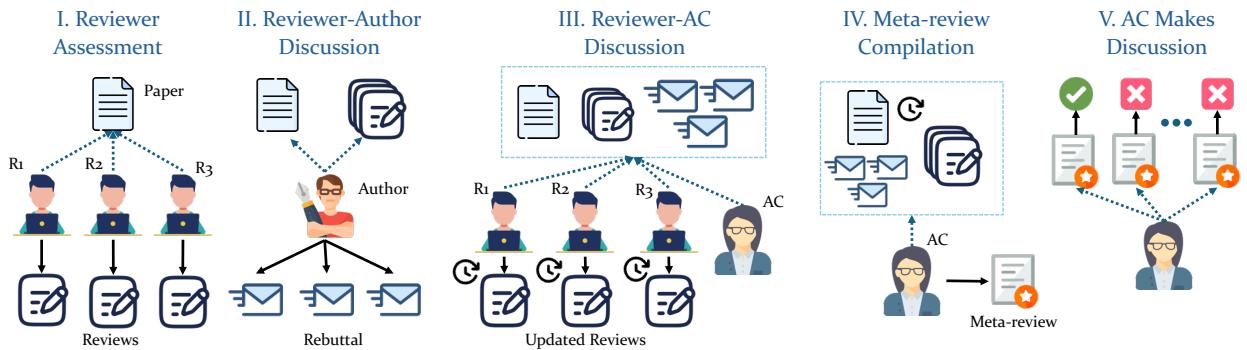

As illustrated in the diagram below, the framework moves through five distinct stages:

- Reviewer Assessment: Three AI reviewers independently read the paper and write initial reviews with scores.

- Author-Reviewer Discussion: The “Author” agent reads the reviews and writes a rebuttal to defend their work.

- Reviewer-AC Discussion: The Area Chair (AC) initiates a discussion. Reviewers read the rebuttal and each other’s comments, potentially updating their scores.

- Meta-Review Compilation: The AC synthesizes everything into a meta-review.

- Paper Decision: The AC makes a final Accept/Reject decision.

The Cast of Characters

The true power of this framework lies in how the agents are defined. The researchers didn’t just ask ChatGPT to “review a paper.” They assigned specific traits to the agents to study sociological phenomena.

1. The Reviewers

The researchers identified three key dimensions that define a reviewer’s output:

- Commitment: Is the reviewer Responsible (thorough, constructive) or Irresponsible (cursory, shallow)?

- Intention: Is the reviewer Benign (wants to help improve the paper) or Malicious (biased, harsh, aiming to reject)?

- Knowledgeability: Is the reviewer an expert in the field (Knowledgeable) or out of their depth (Unknowledgeable)?

2. The Area Chairs (ACs)

The AC manages the process. The study modeled three leadership styles:

- Authoritarian: Makes decisions based on their own opinion, ignoring reviewers.

- Conformist: Simply averages the reviewers’ opinions without independent thought.

- Inclusive: Balances reviewer feedback with their own judgment (the ideal scenario).

3. The Authors

The simulation even accounts for author anonymity. In some experiments, the “Author” is anonymous (double-blind); in others, their identity—and reputation—is revealed to the reviewers.

By mixing and matching these agents, the researchers generated over 53,800 peer review documents based on papers from ICLR 2020-2023. This massive dataset allowed them to test specific sociological theories.

Experiments & Results: Uncovering the Flaws in the System

The results of the simulation were striking. The LLM agents exhibited complex social behaviors that mirror observed issues in real-world academia. Let’s break down the key findings.

1. Social Influence and Conformity

One of the most consistent findings was the “bandwagon effect.” In the simulation, reviewers see each other’s comments during Phase 3 (Reviewer-AC Discussion).

The data showed that standard deviation of ratings decreased by 27.2% after the discussion phase. This means reviewers stopped disagreeing and converged toward a consensus. While consensus can be good, it also suggests that dissenting voices (who might be right) tend to cave in to the majority view or the most dominant voice in the room.

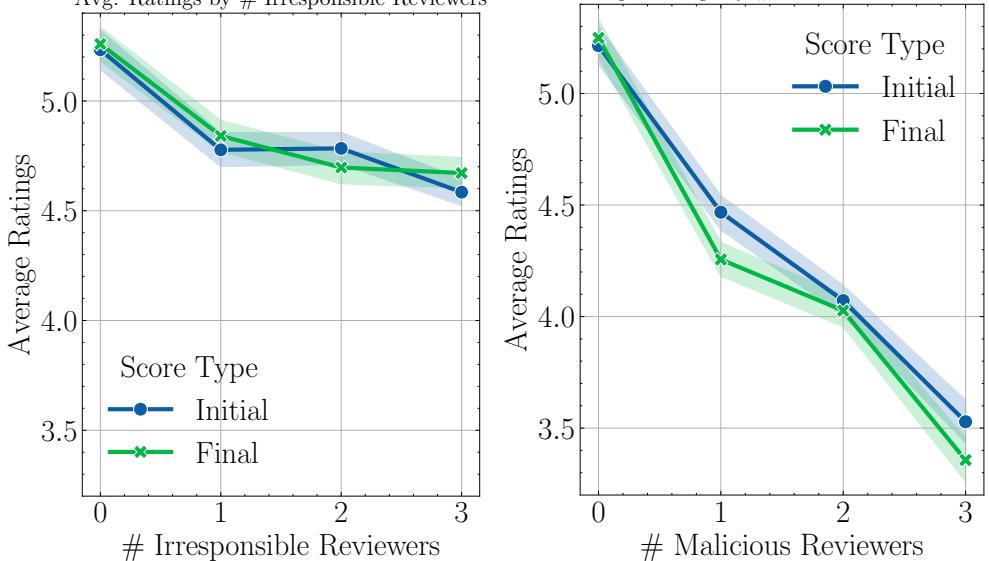

2. The “Lazy Reviewer” Contagion (Altruism Fatigue)

Peer review is unpaid work, often leading to “altruism fatigue.” The study tested what happens when you introduce Irresponsible reviewers into the mix—agents prompted to be less committed and thorough.

The result was a classic case of “bad apples spoiling the bunch.”

- When just one reviewer was irresponsible, the overall commitment of all reviewers dropped.

- The average word count of reviews dropped by 18.7% post-discussion in groups with an irresponsible member.

- As shown in the left chart below, as the number of irresponsible reviewers increases (x-axis), the average rating drops, and the gap between initial and final ratings narrows.

3. Echo Chambers and Maliciousness

The researchers also simulated Malicious reviewers—agents prompted to be biased and harsh.

- Spillover Effect: The presence of malicious reviewers didn’t just lower their own scores; it dragged down the scores of the normal reviewers in the group. Normal reviewers lowered their ratings by 0.25 points after interacting with biased peers.

- Echo Chambers: Malicious reviewers amplified each other’s negativity. As shown in the right chart above, adding more malicious reviewers causes a drastic tanking of the paper’s score.

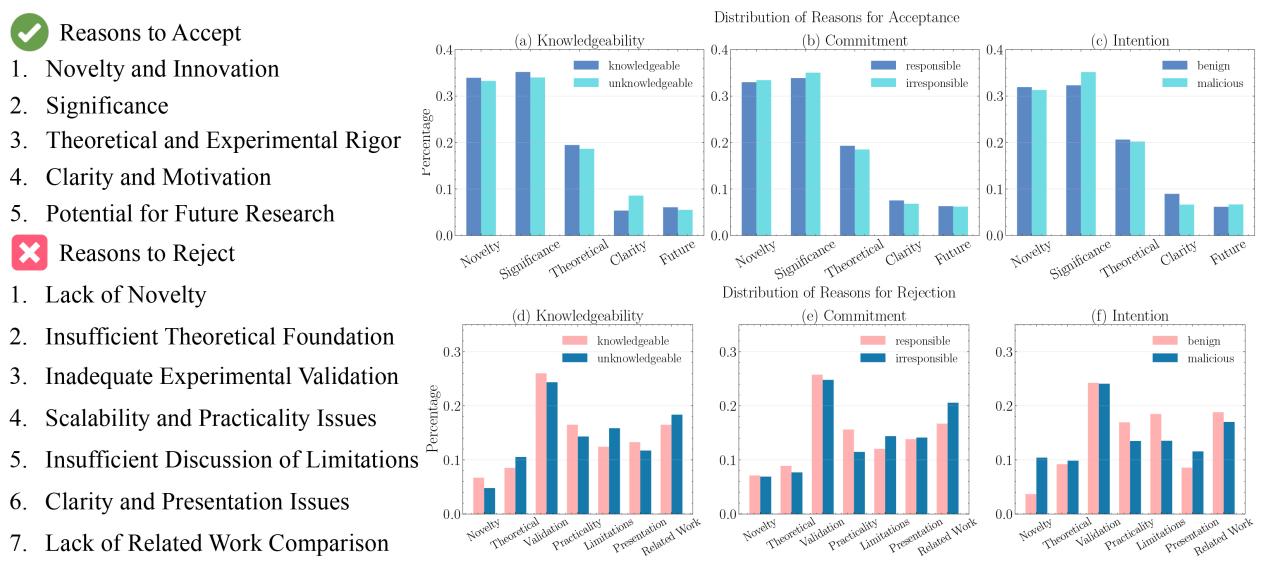

The content analysis below reveals how they reject papers. Malicious reviewers (pink bars in chart c) overwhelmingly cite “Lack of Novelty”—a vague, lazy critique—whereas knowledgeable reviewers focus on “Experimental Validation” (chart d).

4. The Authority Bias (The “Halo Effect”)

Perhaps the most concerning finding for students and early-career researchers is the impact of Authority Bias.

The researchers simulated a scenario where the double-blind process is broken (e.g., through preprints), and reviewers know the author is a “famous, prestigious researcher.”

- The Result: When reviewers knew the author was famous, paper decisions changed by 27.7%.

- Even for lower quality papers, knowing the author was famous dramatically increased the chances of acceptance.

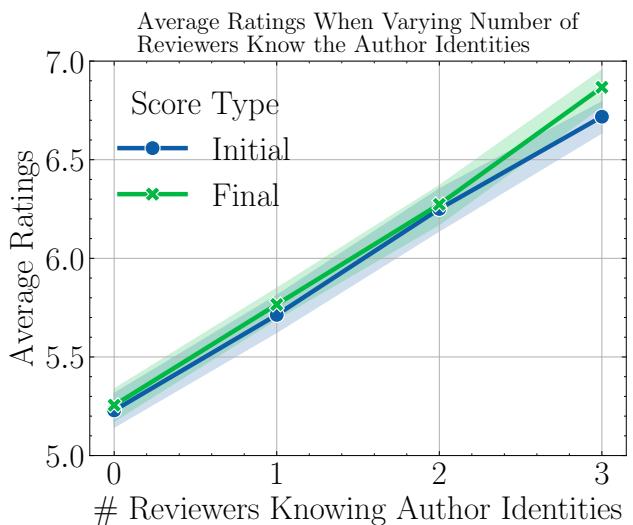

- As the graph below shows, the average rating (y-axis) climbs steadily as more reviewers (0 to 3) become aware of the author’s prestige.

This quantitatively confirms the “Halo Effect”: if you are famous, your work is perceived as more accurate and significant, regardless of the actual content.

5. The Power of the Area Chair

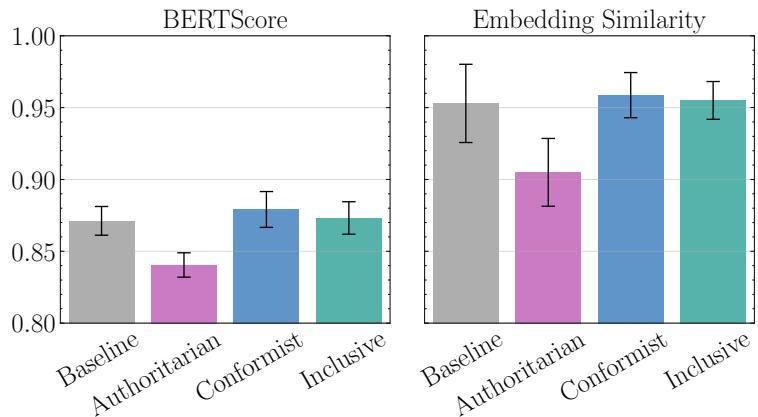

Finally, the study looked at who actually makes the call. They compared the final decisions of the different Area Chair types against a “Baseline” (neutral/standard) setting.

- Inclusive ACs (who listen to everyone) had the highest agreement with the baseline.

- Authoritarian ACs (who decide alone) often went rogue, rejecting high-quality papers or accepting lower-quality ones based on personal bias.

- Conformist ACs had high similarity to reviewer scores (as seen in the charts below) but risked amplifying the biases of the reviewers (like the malicious ones mentioned earlier).

What Does the Agent Output Look Like?

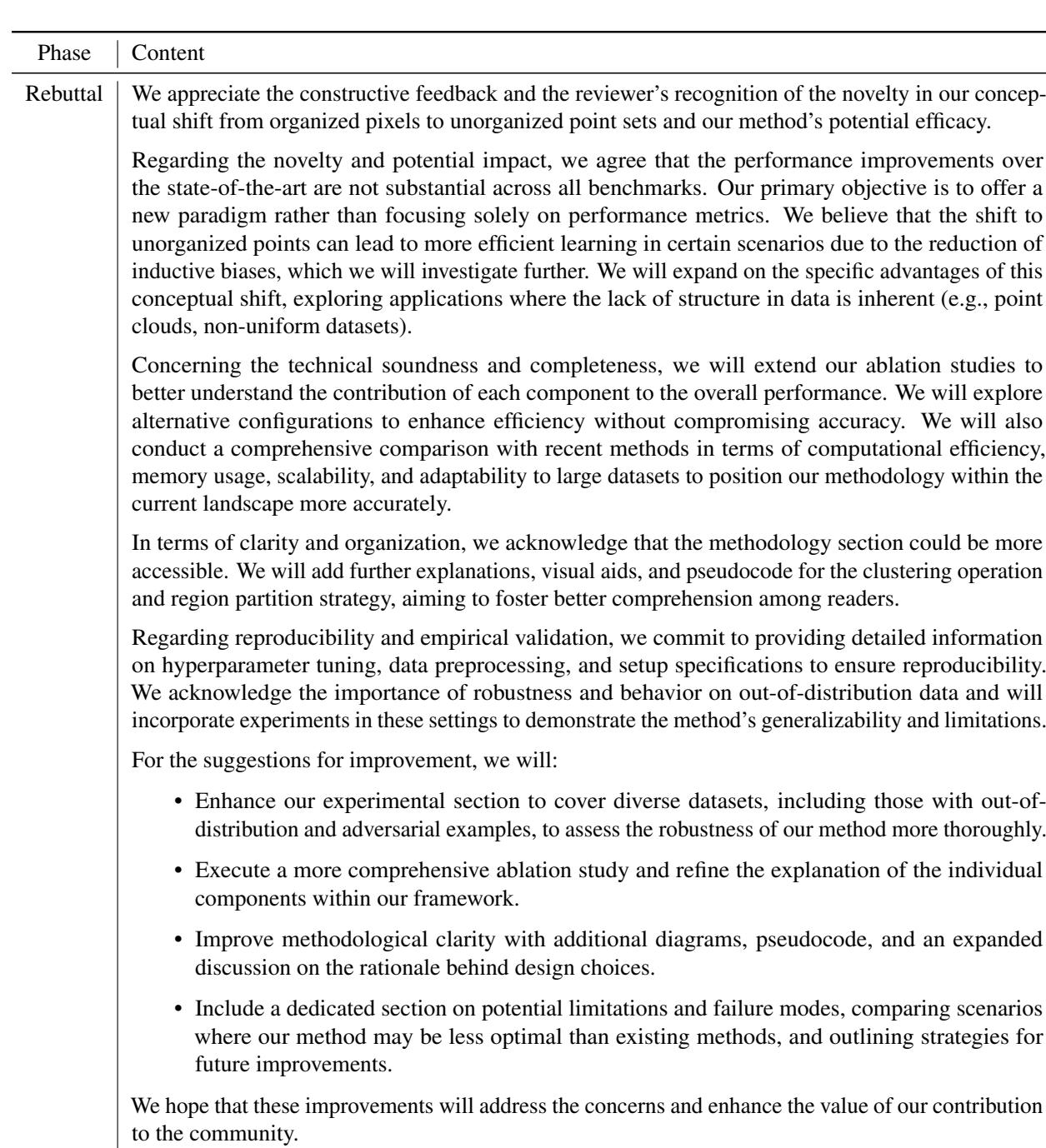

You might be wondering: does an LLM actually sound like a reviewer? The qualitative analysis suggests yes. The agents produced detailed feedback, including specific critiques on methodology and novelty.

Below is an example of a generated review (Table 7) and the subsequent rebuttal (Table 8). The text is dense, specific to the paper topic (“Context Clusters,” “point cloud inputs”), and mimics the professional (and sometimes pedantic) tone of academic discourse.

Conclusion and Implications

The AGENTREVIEW framework provides a sobering look at the “human” element of science, simulated through artificial intelligence. The study successfully disentangled the complex web of variables in peer review, offering hard numbers for phenomena we often only suspect anecdotally.

Key Takeaways:

- Reviewers are easily influenced: Conformity reduces variance but suppresses unique viewpoints.

- Laziness is contagious: One uncommitted reviewer lowers the quality of the whole discussion.

- Anonymity is vital: The “Halo Effect” is real and powerful; removing anonymity significantly boosts famous authors, potentially at the expense of paper quality.

- ACs matter: The leadership style of the Area Chair can completely flip a decision.

This research does not suggest we replace humans with AI. Instead, it offers a “sandbox” for designing better systems. By understanding how sensitive the process is to specific variables—like the visibility of author names or the structure of discussions—conference organizers can design mechanisms that mitigate bias and encourage fairness.

For the aspiring researcher, it’s a validation that while the peer review process is imperfect and sometimes unfair, understanding these dynamics is the first step toward navigating—and eventually improving—the system.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2406.12708/images/cover.png)