Introduction

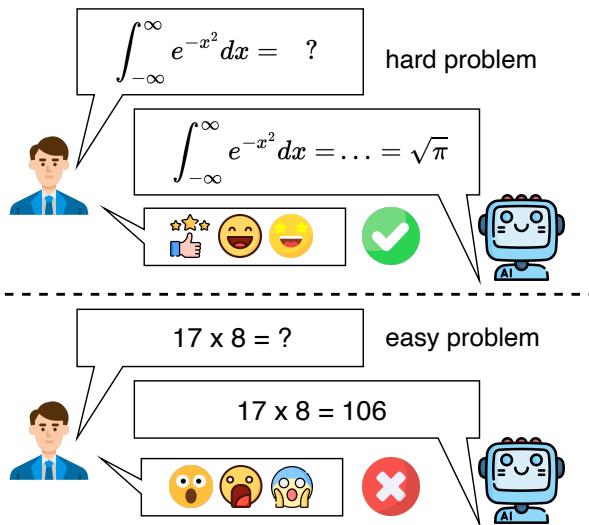

Imagine you are tutoring a student in calculus. They effortlessly solve a complex Gaussian integral, showing a deep understanding of advanced mathematical concepts. Impressed, you ask them a follow-up question: “What is 17 times 8?” The student stares blankly and answers, “106.”

You would be baffled. In human cognition, capabilities are generally hierarchical; if you have mastered advanced calculus, it is taken for granted that you have mastered basic arithmetic. This is the essence of consistency.

However, Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 and Llama do not think like humans. While they have demonstrated expert-level capabilities in law, medicine, and coding, they suffer from a peculiar lack of robustness. A new research paper titled “Can Large Language Models Always Solve Easy Problems if They Can Solve Harder Ones?” explores a specific and counter-intuitive type of failure: the Hard-to-Easy Inconsistency.

As illustrated above, an LLM might correctly solve a complex integral yet fail a simple multiplication task. This blog post dives deep into this research, explaining how the authors quantified this paradox, the benchmark they created, and what this implies for the future of AI trustworthiness.

Background: The Consistency Problem

Before dissecting the new method, we must understand the landscape of LLM reliability. We know LLMs can be sensitive. Previous research has shown that:

- Semantic Inconsistency: Rephrasing a question slightly can flip the model’s answer.

- Order Sensitivity: Changing the order of options in a multiple-choice question changes the prediction.

- Logical Inconsistency: A model might agree with a statement but disagree with its logical negation.

The authors of this paper argue that there is a more fundamental inconsistency that has been overlooked. It is the violation of the difficulty hierarchy. In a rational system, the set of skills required to solve an easy problem is a subset of the skills required for a harder version of that problem. Therefore, failing the easy problem while passing the hard one is a sign of a fundamental reasoning flaw.

The Core Method: ConsisEval

To study this phenomenon scientifically, the researchers couldn’t rely on random questions. They needed a controlled environment where “Easy” and “Hard” were rigorously defined. They introduced ConsisEval, a benchmark designed specifically to test Hard-to-Easy consistency.

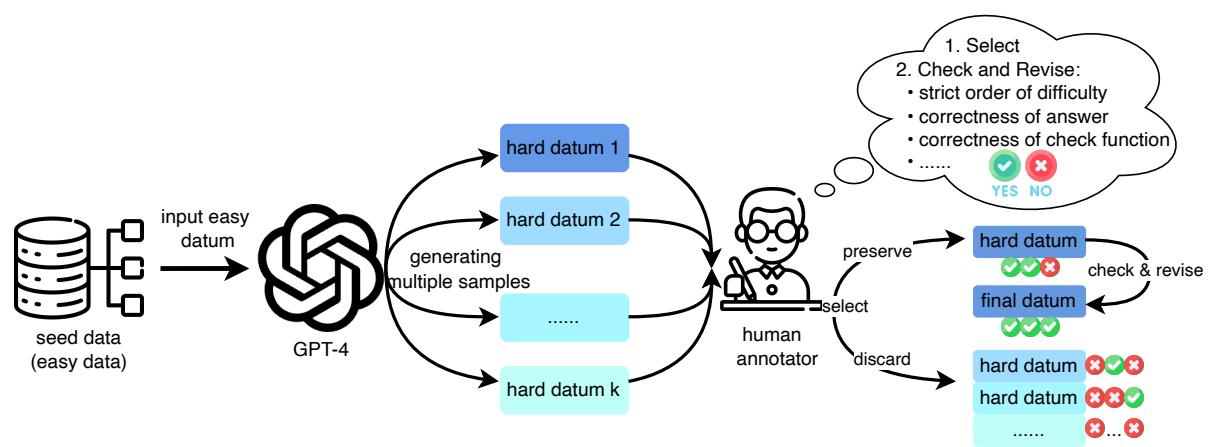

1. Constructing the Dataset

The ConsisEval benchmark covers three critical domains: Code, Mathematics, and Instruction Following.

Unlike traditional benchmarks where questions are independent, ConsisEval uses pairwise data. Each entry contains an Easy Question (\(a\)) and a Hard Question (\(b\)).

- Strict Order of Difficulty: The hard question is derived strictly from the easy one. It often contains the easy question as a sub-step or adds additional constraints. This ensures that mathematically, if you can solve \(b\), you possess the logic to solve \(a\).

The creation process was a hybrid of AI generation and human oversight:

- Seed Data: Easy questions were taken from established datasets (like GSM8K for math or HumanEval for code).

- GPT-4 Synthesis: The researchers prompted GPT-4 to take an easy question and “make it harder” by adding constraints or steps, ensuring the original logic remained a subset of the new problem.

- Human Verification: Annotators rigorously checked the pairs to guarantee the difficulty hierarchy and correctness.

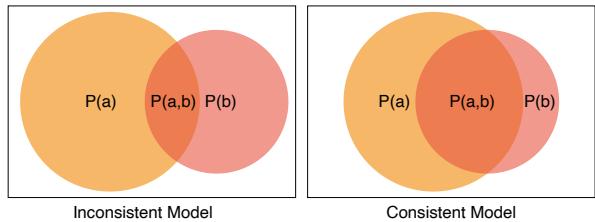

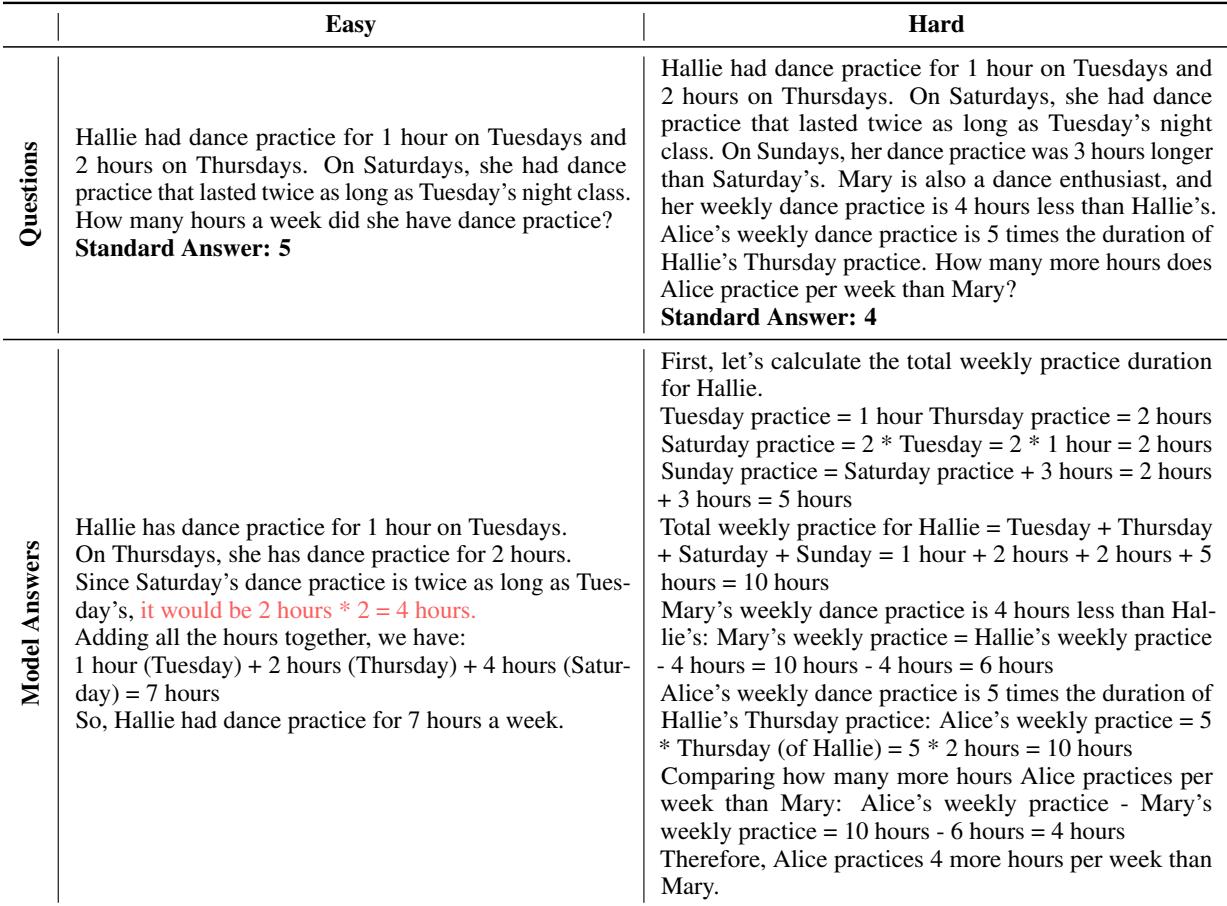

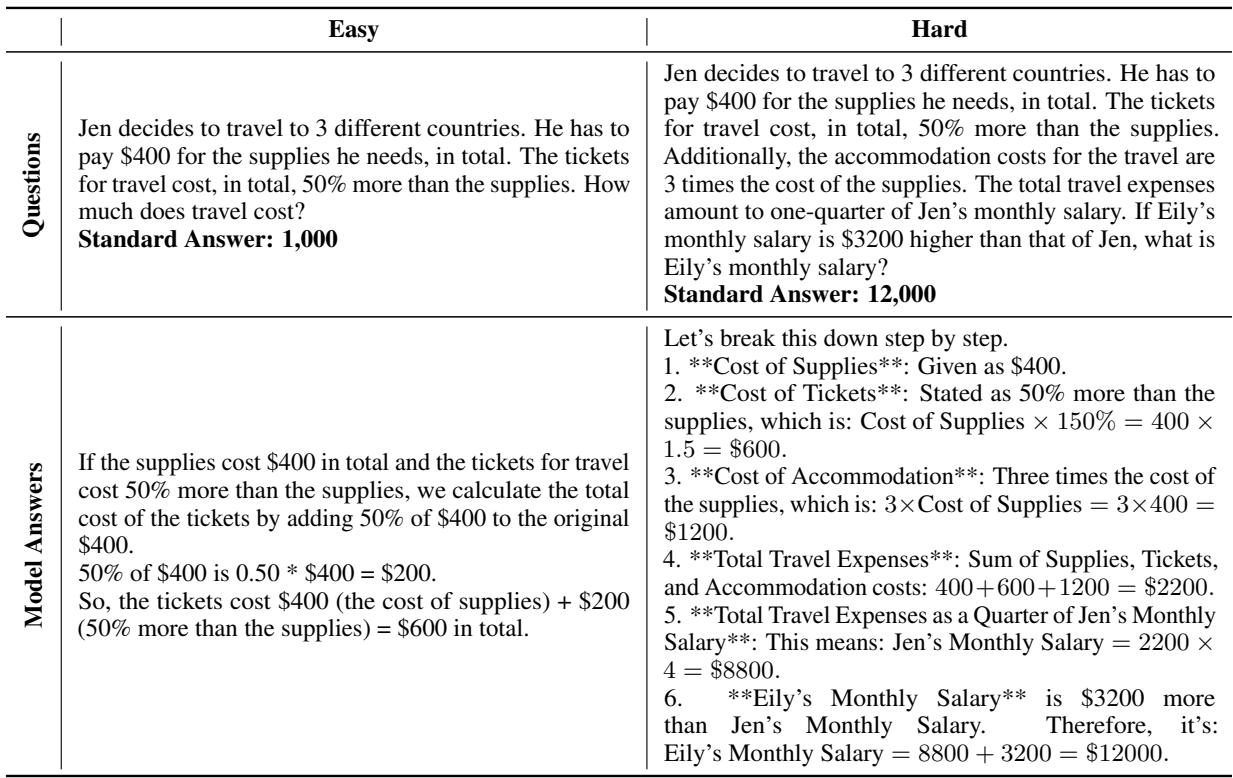

The result is a dataset where the relationship between questions is explicit. For example, in the table below, notice how the “Hard” question (blue text) is simply the “Easy” question (green text) with an added layer of complexity.

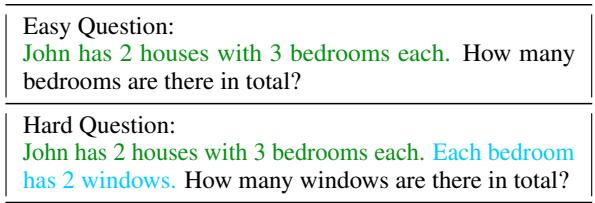

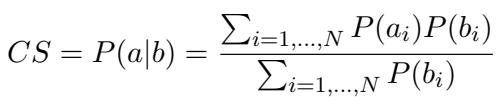

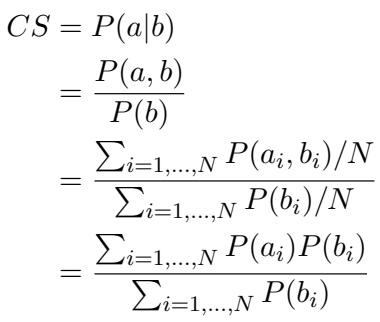

2. Defining the Consistency Score (CS)

How do we measure if a model is consistent? Accuracy alone isn’t enough. We need to look at the conditional probability.

The researchers define the Consistency Score (CS) as the probability that a model answers the easy question correctly, given that it has already answered the hard question correctly.

Visually, we can imagine this using a Venn diagram. In a consistent model (right side of the image below), the circle representing “Solving Hard Problems” is almost entirely contained within the circle of “Solving Easy Problems.” In an inconsistent model (left), there is a large area where the model solves the hard problem but misses the easy one.

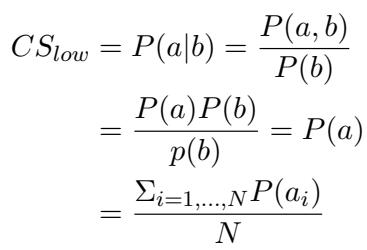

Mathematically, the Consistency Score is calculated as:

Or, expressed conceptually as conditional probability:

Here, \(P(a|b)\) represents the likelihood of success on the easy task (\(a\)) given success on the hard task (\(b\)).

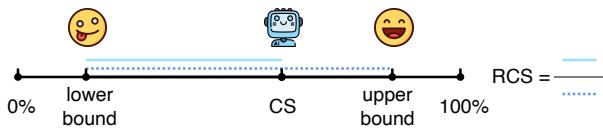

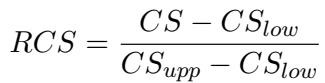

3. The Relative Consistency Score (RCS)

There is a catch with the raw Consistency Score. A model that is terrible at everything (0% accuracy on both easy and hard) would technically have a high consistency score because it never encounters the “pass hard / fail easy” paradox. But that’s not useful.

To address this, the authors introduce the Relative Consistency Score (RCS). This metric contextualizes a model’s consistency against its raw capability.

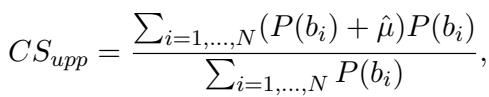

The RCS measures where a model sits between a theoretical “Lower Bound” (the worst possible consistency for its accuracy level) and an “Upper Bound” (the best possible consistency).

The formula normalizes the score:

To calculate this, they derived mathematical bounds based on the model’s performance on the dataset. The lower bound (\(CS_{low}\)) assumes the model’s success on easy and hard questions is independent (random):

The upper bound (\(CS_{upp}\)) assumes the model is as consistent as theoretically possible given the difficulty gap:

4. Estimating Probabilities

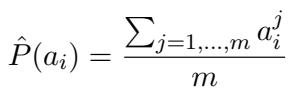

In standard benchmarks, we usually ask an LLM a question once (greedy decoding) and check if it’s right or wrong. However, LLMs are probabilistic engines. To get an accurate Consistency Score, we need the true probability (\(P\)) that a model solves a problem.

The researchers used sampling techniques. For open-source models, they sampled answers 20 times to estimate the probability:

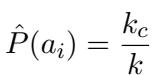

For expensive closed-source models (like GPT-4), they used an Early Stopping technique to save costs while retaining statistical validity. They stop sampling as soon as a correct answer is found (since high-performance models usually get it right quickly), estimating the probability as:

Experiments and Results

The researchers tested a wide array of models, including GPT-4, GPT-3.5, Claude-3 Opus, Llama-2/3, and Qwen. The results provide a fascinating snapshot of the current state of AI reliability.

Main Findings

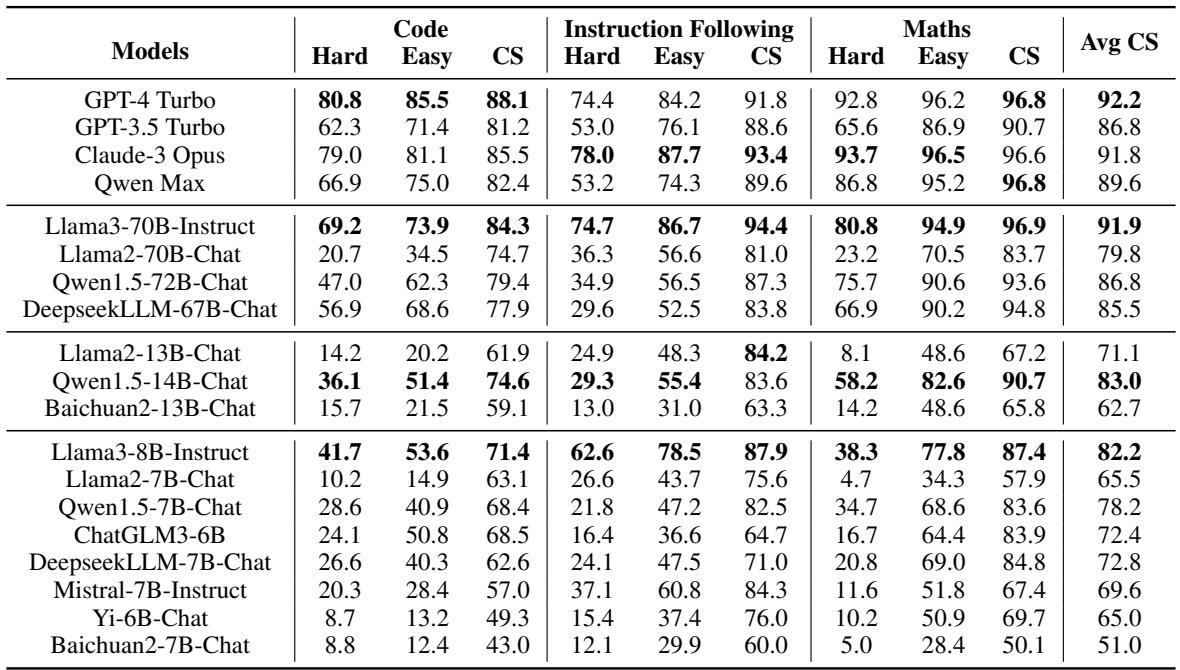

The table below summarizes the performance across all three domains (Code, Instructions, Math).

Key Takeaways from the Data:

- GPT-4 Turbo is the Consistency King: It achieved the highest average Consistency Score (92.2%). This suggests that stronger models are generally more rational in their problem-solving hierarchy.

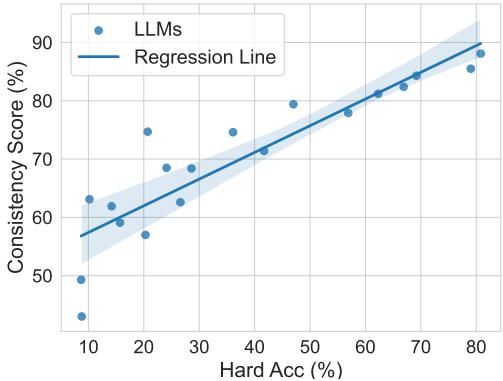

- Capability Correlates with Consistency: There is a strong positive relationship between a model’s raw accuracy on hard problems and its consistency score. As models get smarter, they tend to make fewer “stupid” mistakes.

- Exceptions Exist: Interestingly, Claude-3 Opus, despite being a very strong model (sometimes outperforming GPT-4 on specific math tasks), had a slightly lower Consistency Score. This proves that high accuracy does not automatically guarantee high consistency.

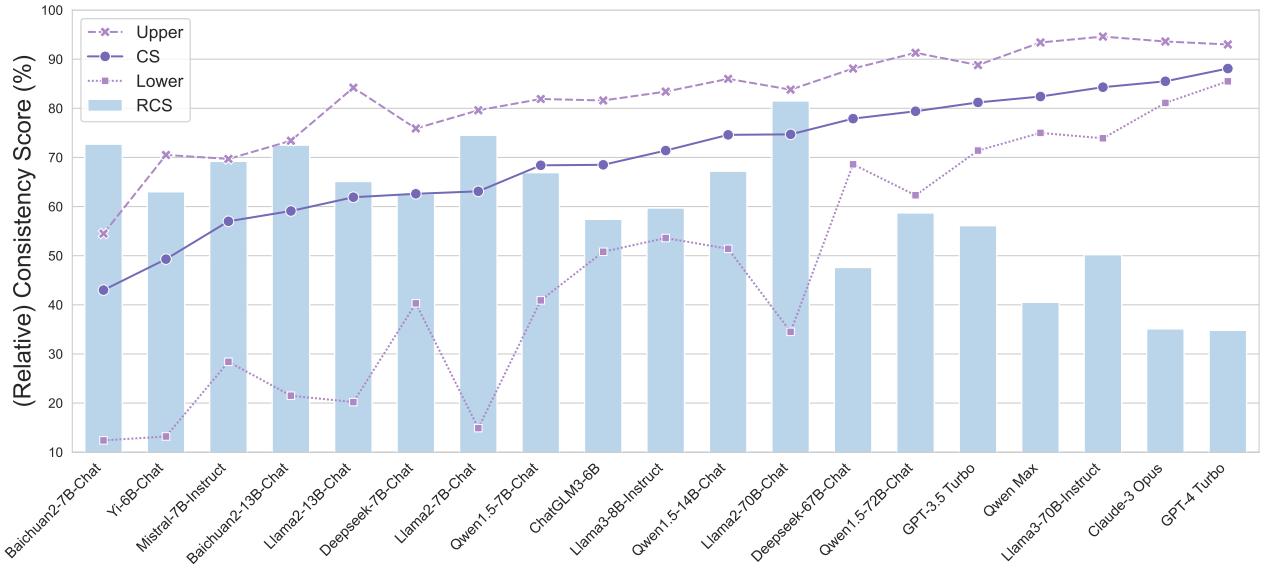

Relative Consistency Analysis

When applying the Relative Consistency Score (RCS), we see that even the best models have room for improvement.

In the Code domain (shown below), GPT-4 Turbo has a high raw CS (88.1%), but its RCS is only 34.8%. This means that relative to its massive intelligence, it is still underperforming in consistency. It should be doing even better. Conversely, some weaker models like Llama-2-70B have high RCS, meaning they are very consistent despite being less capable overall—they know what they know, and they know what they don’t.

Why Do LLMs Fail Easy Problems?

The numbers tell us that they fail, but the qualitative analysis tells us why. The authors conducted case studies to analyze specific instances where GPT-4 solved a hard problem but failed the easy version.

1. Distraction by Redundant Information

LLMs often struggle when easy problems contain “fluff” or extra details. In the example below, the model gets confused by the mention of “Thursday” in the easy prompt, misapplying it to the calculation.

2. Overthinking and Misinterpretation

Sometimes, the model anticipates complexity that isn’t there. In this travel cost example, the model correctly calculates the complex scenario (Hard) but misinterprets the simple request in the Easy scenario, calculating only ticket costs instead of the total.

3. Simple Computational Errors

Paradoxically, the “Hard” questions often force the model into a deeper reasoning mode (like Chain-of-Thought), which acts as a guardrail against errors. Easy questions might trigger a quicker, less careful generation path, leading to basic arithmetic fails.

Implications: How Do We Fix It?

The paper concludes with two significant experiments regarding how to improve consistency.

1. Train on Harder Data

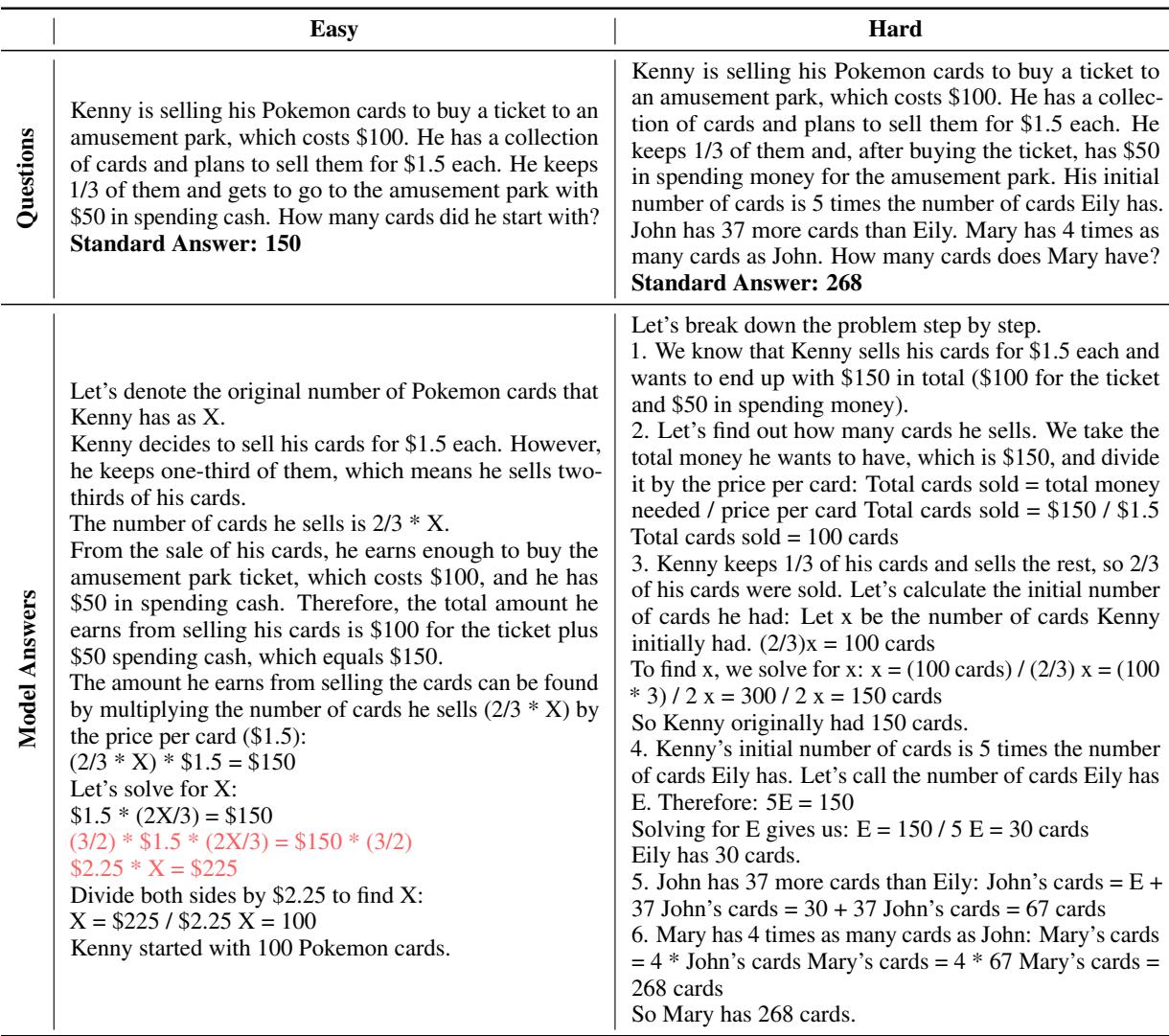

The researchers fine-tuned models on datasets with varying ratios of easy vs. hard data. The results were clear: Hard data enhances consistency.

As shown in Figure 6, as the proportion of hard data in the training set increases (x-axis), the Consistency Score (CS) rises. This suggests that exposing models to difficult reasoning patterns generalizes downwards to easier tasks better than the reverse.

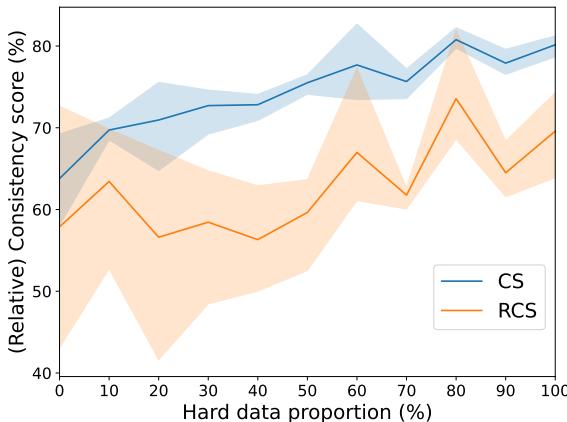

2. Use Hard Examples in Prompts

For users who can’t retrain models, the solution lies in In-Context Learning (ICL). When providing “few-shot” examples in a prompt, using hard examples yields better consistency than using easy examples.

Conclusion

The research presented in “Can Large Language Models Always Solve Easy Problems if They Can Solve Harder Ones?” highlights a critical gap between artificial and human intelligence. While humans build knowledge like a pyramid—where a broad base of simple skills supports a peak of advanced capability—LLMs are more like a Jenga tower. They can reach dizzying heights of performance, but missing blocks near the bottom make them surprisingly unstable.

The introduction of ConsisEval and the Consistency Score gives the AI community a new lens through which to view model evaluation. It forces us to ask not just “How many questions did the model get right?” but “Does the model’s performance make logical sense?”

The findings offer a clear path forward: to build more trustworthy AI, we shouldn’t just focus on solving the hardest riddles. We must ensure that in the pursuit of genius, the models don’t lose their common sense. By training on harder data and rigorously testing against consistency benchmarks, we can move closer to AI that is not just powerful, but reliable.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2406.12809/images/cover.png)