The Rise of the AI Judge

In the rapidly evolving landscape of Artificial Intelligence, we face a bottleneck: evaluation. As Large Language Models (LLMs) become more capable, evaluating their outputs has become prohibitively expensive and time-consuming for humans. If you are developing a new model, you cannot wait weeks for human annotators to grade thousands of responses.

The industry solution has been “LLM-as-a-Judge.” We now rely on powerful models, like GPT-4, to grade the homework of smaller or newer models. These “Evaluator LLMs” decide rankings on leaderboards and influence which models get deployed. But this reliance rests on a massive assumption: that the Evaluator LLM actually knows what a good (or bad) answer looks like.

What if the judge is blind to specific types of errors? What if an evaluator gives a perfect score to an answer that is factually wrong or mathematically incoherent?

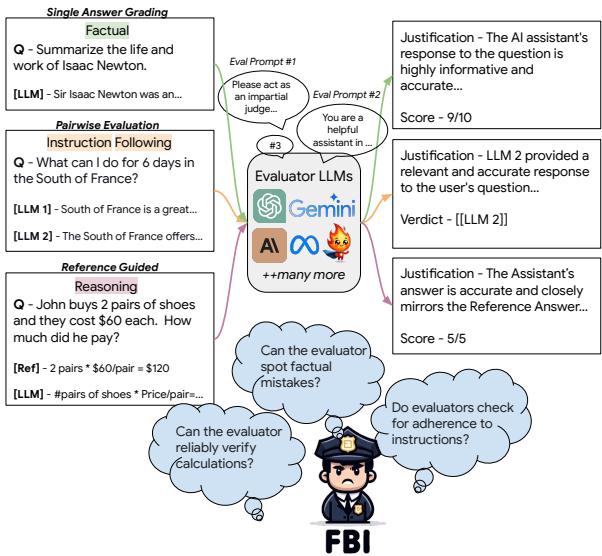

In the paper “Finding Blind Spots in Evaluator LLMs with Interpretable Checklists,” researchers from AI4Bharat and IIT Madras propose a novel framework called FBI. No, not the federal agency—it stands for Finding Blind spots with Interpretable checklists. Their work creates a rigorous stress test for AI judges, revealing that even our most advanced models often fail to notice when an answer is fundamentally broken.

The Problem with Current Evaluation

Before diving into the FBI framework, we must understand the status quo. Currently, when researchers want to know if their model is good, they often use metrics that correlate with human judgment. If GPT-4 gives a response a high score, and a human gives it a high score, we assume GPT-4 is a reliable judge.

However, correlation is not enough. As LLMs are tasked with complex jobs—writing code, reasoning through math, or following multi-step instructions—we need “fine-grained” assessment. A generic “9/10” score is useless if the model failed to follow a negative constraint (e.g., “do not use the word ‘happy’”).

The researchers argue that we need to treat LLM evaluation like software testing. In software engineering, we use “unit tests” to break code and see if it fails gracefully. The FBI framework applies this logic to Evaluator LLMs.

The FBI Framework: Stress-Testing the Judge

The core intuition behind FBI is simple but powerful: If I take a perfect answer and deliberately break it in a specific way, the Evaluator LLM should lower the score. If the score remains the same, the evaluator has a “blind spot.”

As shown in Figure 1 above, the framework operates by presenting an Evaluator LLM with questions and responses. The system utilizes different prompting strategies (like providing rubrics or asking for reasoning) to see if the evaluator can detect quality drops.

To systematize this, the researchers focused on four critical capabilities that any robust LLM should possess:

- Factual Accuracy: Does the answer contain true information?

- Instruction Following: Did the model follow all constraints?

- Long-Form Writing: Is the text coherent, grammatical, and consistent?

- Reasoning Proficiency: Are the math and logic correct?

Constructing the Dataset: The Art of Perturbation

To test these capabilities, the researchers didn’t just collect bad answers; they manufactured them. They started with high-quality “Gold Answers” generated by GPT-4-Turbo. Then, they introduced “perturbations”—targeted modifications designed to introduce a specific error while keeping the rest of the answer intact.

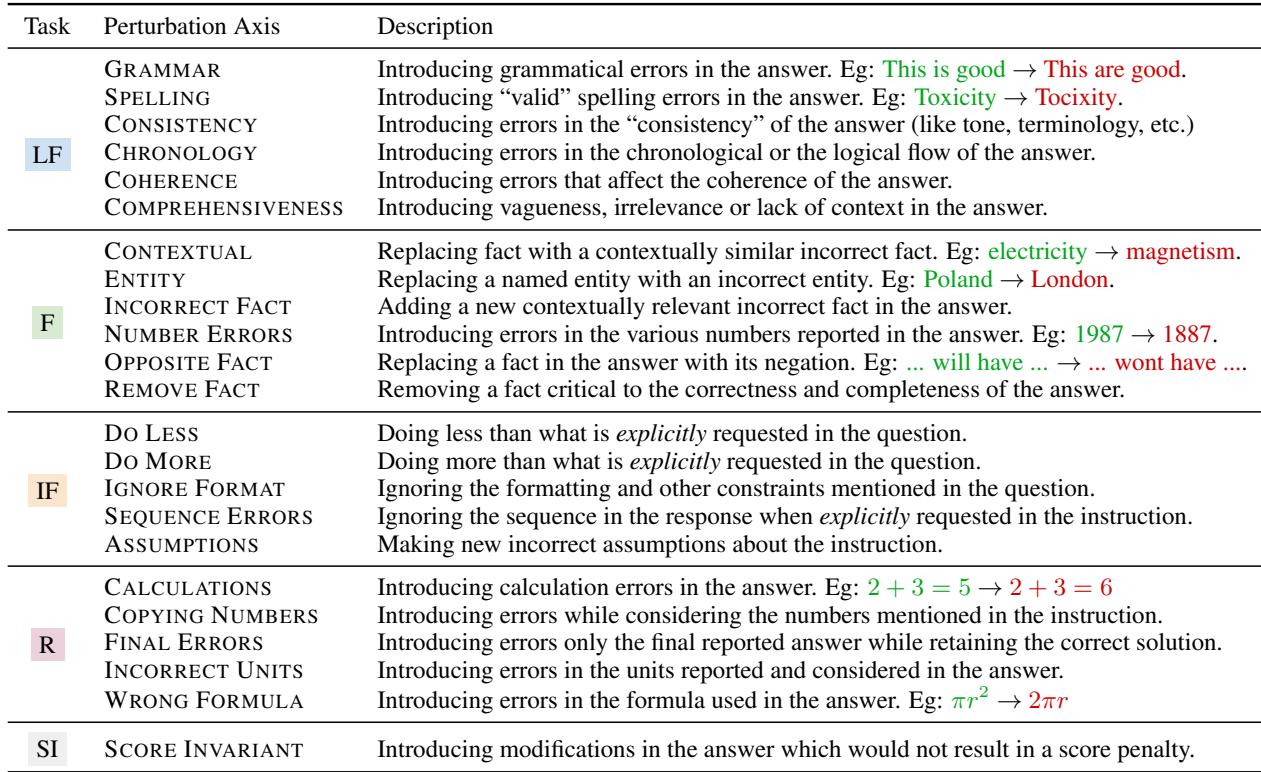

They defined 22 distinct perturbation categories. This granularity is what makes the FBI framework “interpretable.” If an evaluator fails, we know exactly why (e.g., it can’t spot calculation errors, or it ignores spelling mistakes).

The table above details these categories. For example:

- Factual (Opposite Fact): Changing a sentence to claim the exact opposite (e.g., “will have” becomes “won’t have”).

- Reasoning (Calculation): Changing a math step like \(2+3=5\) to \(2+3=6\).

- Instruction Following (Do Less): Deliberately ignoring a part of the prompt.

- Long Form (Coherence): Scrambling the logical flow of a paragraph.

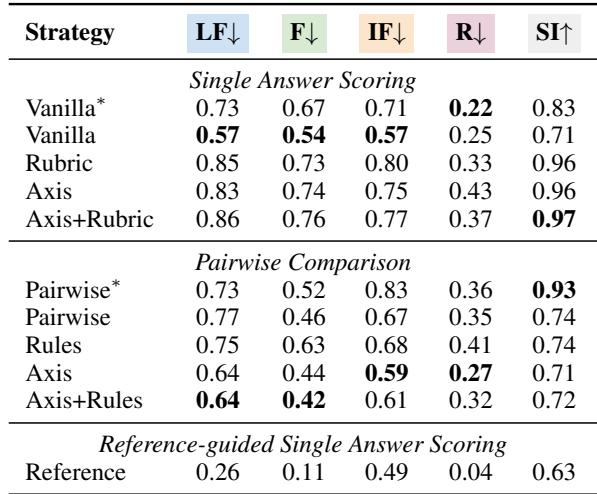

The researchers generated 2,400 of these perturbed answers. Crucially, they used a Human-in-the-Loop process. Automated perturbation isn’t perfect, so graduate students manually verified these perturbed answers to ensure they were indeed incorrect and that the error was relevant to the category.

They also created “Score Invariant” perturbations—changes that shouldn’t lower the score (like paraphrasing). This acts as a control group to ensure the evaluator isn’t just penalizing any change.

How the Judges Were Judged

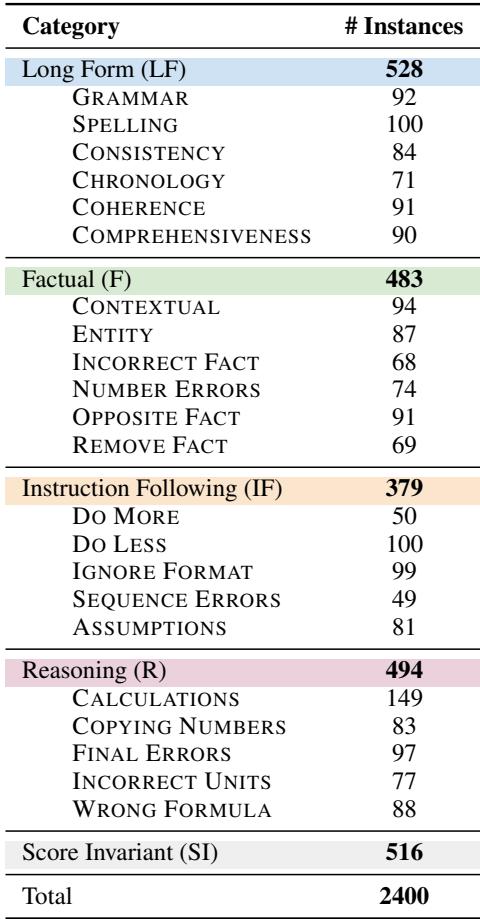

With this dataset of 2,400 flawed answers, the researchers tested five prominent LLMs often used as evaluators, including GPT-4-Turbo, Gemini-1.5-Pro, Claude-3-Opus, and Llama-3-70B.

They tested them across three different evaluation paradigms commonly used in the industry:

- Single-Answer Scoring: The model looks at one answer and gives it a score (e.g., 1-10).

- Pairwise Comparison: The model looks at the “Gold” answer and the “Perturbed” answer and decides which is better.

- Reference-Guided Scoring: The model scores the answer while looking at a “Gold” reference key.

They also experimented with different prompting strategies, such as Vanilla (just ask for a score), Rubric (provide a grading guide), and Axis (tell the model to focus specifically on “Factuality” or “Grammar”).

The Results: A Crisis of Confidence

The results were stark. The study found that Evaluator LLMs are currently far from reliable. On average, even the best models failed to identify quality drops in over 50% of cases.

1. GPT-4-Turbo Struggles with Basics

Let’s look at the performance of GPT-4-Turbo, widely considered the state-of-the-art evaluator.

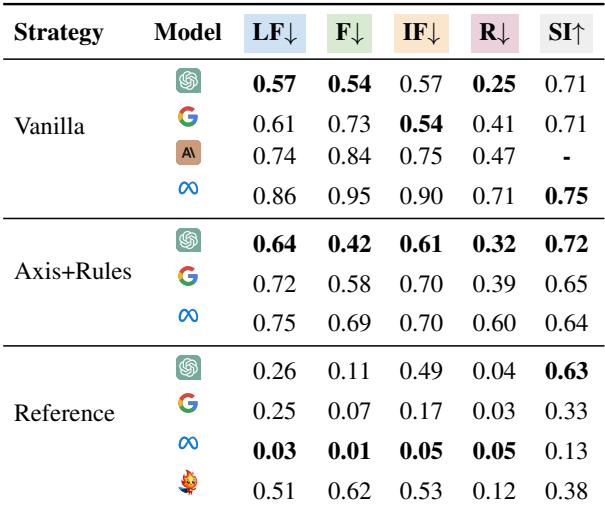

In the table above, the numbers represent the percentage of times the evaluator failed to penalize the perturbed answer (lower is better).

- Factual Accuracy: In single-answer scoring, GPT-4 failed to penalize factual errors roughly 67-76% of the time depending on the strategy.

- Instruction Following: It missed instruction violations 57-80% of the time.

- Reasoning: It performed best here, but still missed 22-43% of errors.

These aren’t subtle errors. These are answers where a “not” was deleted, or a math equation was deliberately broken. If a human teacher missed 70% of factual errors in a student’s essay, they would be fired.

2. Complexity Doesn’t Always Help

The researchers found a surprising trend regarding prompting strategies. You might assume that giving the model a detailed rubric (the Rubric or Axis+Rubric strategies) would improve performance.

However, looking at the Single Answer Scoring section of the table above, the Vanilla strategy (simply asking for a score) often outperformed the complex Rubric strategies. Adding more instructions sometimes seemed to confuse the model or dilute its focus, making it less sensitive to errors.

However, in Pairwise Comparison (choosing between two answers), the opposite was true: having detailed Rules helped the models make better decisions.

3. Comparing the Models

Is this just a GPT-4 issue? Unfortunately, no. The researchers compared GPT-4 against other heavyweights.

As shown in Table 4, GPT-4-Turbo generally outperformed Llama-3 and others in reference-free evaluation. However, Llama-3-70B-Instruct showed surprising strength in Reference-Guided evaluation (where the correct answer is provided to the judge).

A fascinating quirk appeared here: Llama-3 was extremely strict. While it caught almost all errors when given a reference, it also penalized the “Score Invariant” (correct) answers heavily. It seems Llama-3 struggles to differentiate between a wrong answer and an answer that is correct but phrased differently from the reference key.

4. The “I See It, But I Don’t Care” Phenomenon

One of the most concerning findings was the disconnect between the evaluator’s explanation and its score.

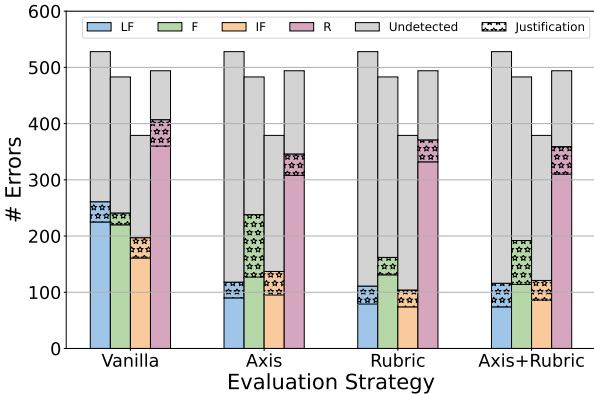

Most “LLM-as-a-Judge” prompts ask the model to explain its reasoning before assigning a score (Chain-of-Thought). The researchers analyzed these explanations to see if the model noticed the error but refused to deduct points.

The chart above illustrates this gap. The striped purple sections represent cases where the model’s explanation explicitly mentioned the error (e.g., “The user asked for a list, but the model wrote a paragraph”), yet the numerical score remained perfect.

While checking explanations helps catch a few more errors, the vast majority (the grey bars) remain completely undetected by both the score and the text generation.

Blind Spots by Category

The FBI framework revealed specific weaknesses inherent to these models:

- Fluency is Overrated: Evaluators are easily charmed by confident, fluent writing. A perturbed answer that is grammatically smooth but factually wrong often gets a pass.

- Instruction Following: “Negative constraints” (e.g., “Do not use bullet points”) are frequently ignored by evaluators. If the answer looks helpful, the evaluator forgives the formatting violation.

- Math Blindness: While reasoning was the strongest category, models still struggled to penalize “Wrong Formula” or “Incorrect Units” if the final text looked authoritative.

Conclusion: The Verdict on the Judges

The FBI paper delivers a sobering reality check for the AI community. As we race to build more powerful models, our yardsticks—the Evaluator LLMs—are warped.

The key takeaways from this research are:

- Don’t Trust the Score: An automated score of 10/10 does not guarantee factual accuracy or instruction adherence.

- Pairwise is Flawed: Even when directly comparing a correct answer against a broken one, models often fail to pick the winner accurately.

- References are Crucial: Evaluators perform significantly better when provided with a Gold Reference answer, though this is difficult in open-ended generation tasks where a single “right” answer doesn’t exist.

The FBI framework provides a necessary toolkit for “meta-evaluation.” Before using an LLM to grade your dataset, you should run it through a checklist like FBI to understand its biases and blind spots. Until Evaluator LLMs improve, we must remain cautious, keeping humans in the loop for high-stakes decisions and viewing AI leaderboards with a healthy dose of skepticism.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2406.13439/images/cover.png)