Have you ever read a comment thread on the internet and thought, “Wow, this is actually a productive conversation”? It’s rare. Most online disagreements devolve into shouting matches. But for researchers in Natural Language Processing (NLP) and social science, understanding what makes a conversation “constructive”—where participants open their minds, reach consensus, or simply disagree politely—is a massive, complex puzzle.

To solve this, we generally have two toolkits. On one side, we have feature-based models. These are the “old reliable” tools (like logistic regression) that use specific, hand-crafted rules. They are easy to interpret—you know exactly why the model made a decision—but they often require expensive human annotation to label data.

On the other side, we have Neural Models, specifically Pre-trained Language Models (PLMs) like BERT or GPT-4. These are the powerhouses. They digest raw text and often achieve higher accuracy. But they come with a catch: they are “black boxes.” We don’t know how they reach their conclusions. Worse, they are prone to “shortcut learning,” where they memorize superficial patterns (like specific keywords) rather than understanding the actual dynamics of a conversation.

In the paper “An LLM Feature-based Framework for Dialogue Constructiveness Assessment,” researchers from the University of Cambridge and Toshiba propose a way to break this dichotomy. They introduce a framework that combines the interpretability of feature-based models with the raw power of Large Language Models (LLMs).

In this post, we will tear down their methodology, explore how they use LLMs as “feature extractors” rather than final predictors, and look at why this hybrid approach might just be better than throwing a massive neural network at the problem.

The Problem with Current Approaches

Before diving into the solution, we need to understand the specific limitations the authors address.

1. The Cost of Interpretability

If you want to know why a conversation failed, you need features. Did the user use insults? Did they hedge their claims (e.g., “I think that maybe…”)? Did they ask questions? Traditional feature-based models require these inputs. Historically, getting high-quality features meant hiring humans to read thousands of comments and label them as “hostile” or “cooperative.” This is slow and expensive.

2. The Trap of Shortcut Learning

Neural networks are lazy learners. If you train a model to detect “constructive” debates, and your training data features a lot of polite discussions about veganism, the model might just learn that the word “tofu” equals “constructive.” It ignores the structure of the argument and focuses on the topic. This is called shortcut learning. When you test that same model on a debate about Brexit, it fails miserably because the “tofu” shortcut doesn’t exist there.

The Solution: The LLM Feature-Based Framework

The authors propose a “best of both worlds” approach. Instead of using an LLM to predict the final outcome directly, they use the LLM to extract features. These features are then fed into a simple, interpretable model (like Ridge or Logistic Regression).

Here is the high-level workflow of their framework:

As shown in Figure 1, the process splits into two parallel streams of feature extraction:

- Simple Algorithmic Heuristics: Code-based rules to count things like pronouns or politeness markers.

- Prompting an LLM: Using GPT-4 to analyze complex linguistic behaviors like dispute tactics or argument quality.

These two streams merge to create a statistical profile of the dialogue, which is then fed into a transparent classifier.

Step 1: Feature Extraction

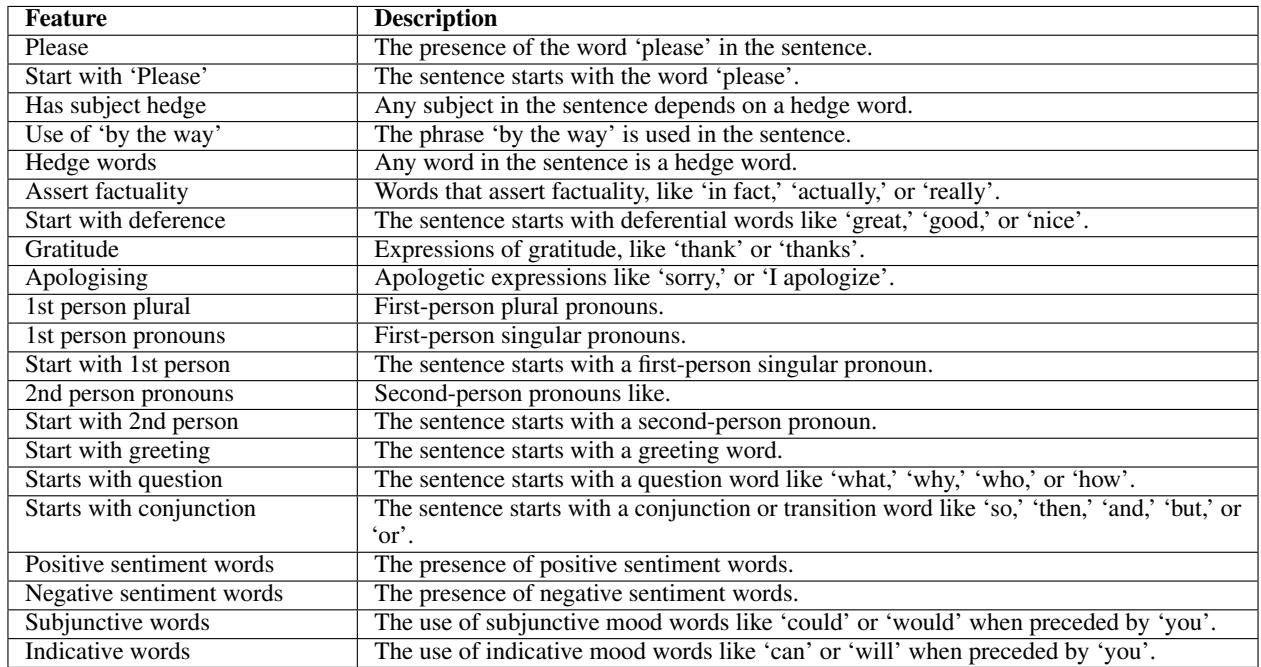

The core of this paper is the rich set of linguistic features the authors curate. They don’t just dump text into a model; they look for specific signals known to influence human interaction.

They organize these signals into six dataset-independent sets.

Let’s break down these feature sets, as they are the “senses” the model uses to understand the world.

The Heuristic Features (The “Old School” Stream)

These are features that can be extracted with code libraries like Convokit. They are fast and deterministic.

- Politeness Markers: Does the speaker use “please,” “thank you,” or “sorry”? Do they start with a greeting?

- Collaboration Markers: This looks for signs of working together. It counts things like “hedging” terms (indicating humility/uncertainty) or how often participants reference the same concepts.

The LLM-Generated Features (The “New School” Stream)

This is where the innovation lies. Some concepts are too subtle for simple code. Identifying “condescension” or “counter-arguments” requires semantic understanding. The authors prompt GPT-4 to act as an annotator for these features.

- Dispute Tactics: How are the participants fighting? Are they “name-calling”? Are they “derailing” the conversation? Or are they offering a “refutation” based on evidence?

- Quality of Arguments (QoA): This is a novel feature introduced in this paper. The LLM is asked to grade the quality of arguments on a scale of 0-10.

- Style and Tone: Is the text formal? Is the sentiment negative? Is there “epistemic uncertainty” (e.g., “I believe this might be true” vs. “This is true”)?

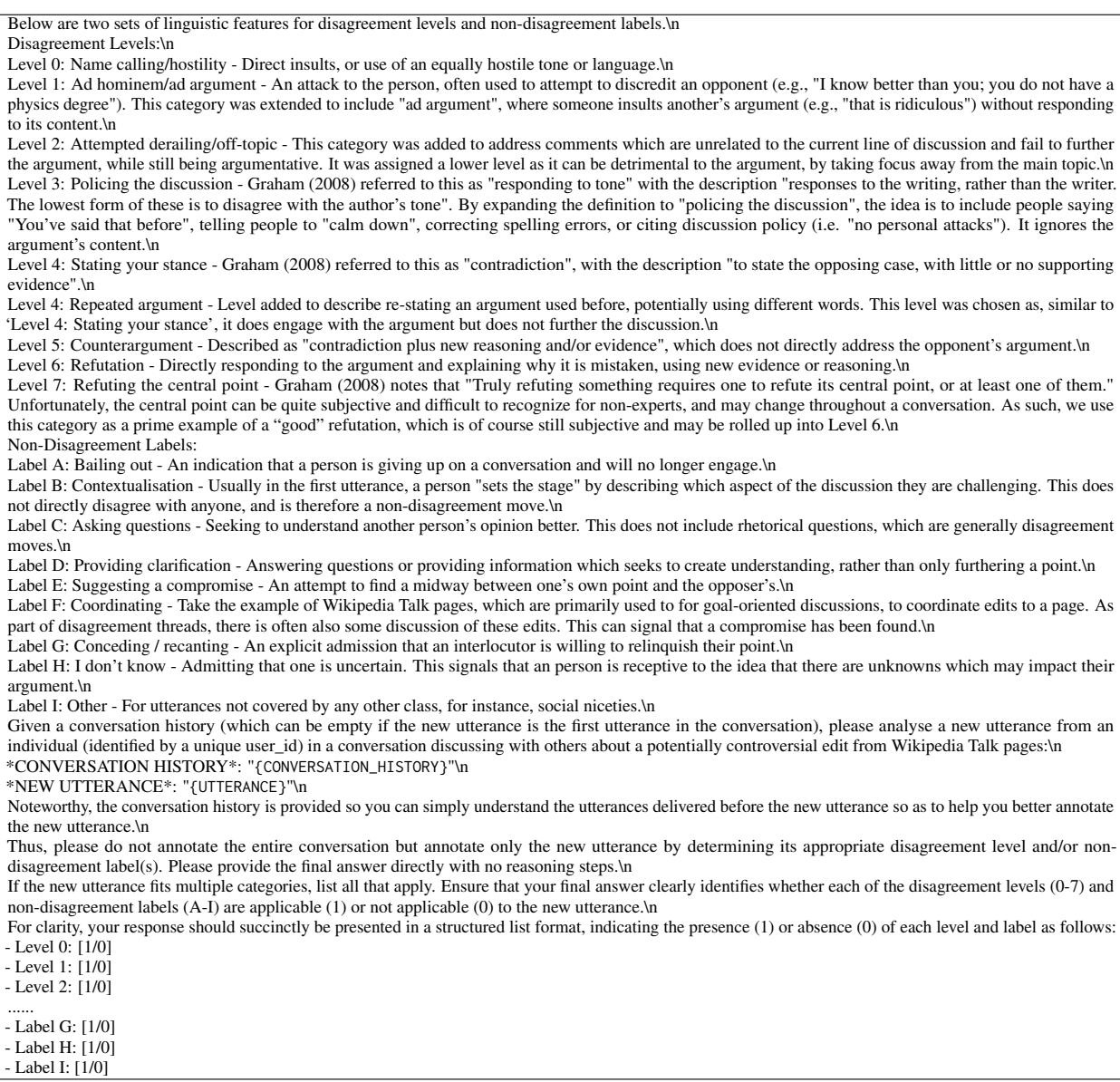

To get these features, the researchers design specific prompts. For example, to extract Dispute Tactics, they feed the conversation history to the LLM and ask it to categorize the latest utterance.

By asking the LLM to output a structured list (0 or 1 for each category), they convert unstructured text into structured data that a regression model can use.

Step 2: From Utterance to Dialogue

A conversation is a sequence of turns. The features above are extracted at the utterance level (per sentence/comment). To classify the entire dialogue, the framework computes statistics across the whole exchange:

- Average (\(\bar{x}\)): e.g., “What was the average level of politeness in this conversation?”

- Gradient (\(\nabla\)): e.g., “Did the politeness increase or decrease as the conversation went on?”

This captures not just the state of the conversation, but its trajectory.

Experimental Setup

To prove this framework works, the authors tested it on three very different datasets:

- Opening-Up Minds (OUM): Dialogues about controversial topics (Brexit, Veganism, COVID-19). The goal is to predict if a participant became more open-minded after the chat.

- Wikitactics: Wikipedia Talk Page disputes. The goal is to predict if the dispute escalated (bad) or was resolved (good).

- Articles for Deletion (AFD): Debates on whether a Wikipedia article should be deleted. The goal is to predict the “Keep” vs. “Delete” outcome.

They compared their LLM Feature-based Model against heavy hitters:

- Baselines: Bag-of-Words, GloVe Embeddings.

- Neural Models: Longformer (a version of BERT designed for long text), and GPT-4o (zero-shot and few-shot prompting).

Results: Accuracy and Performance

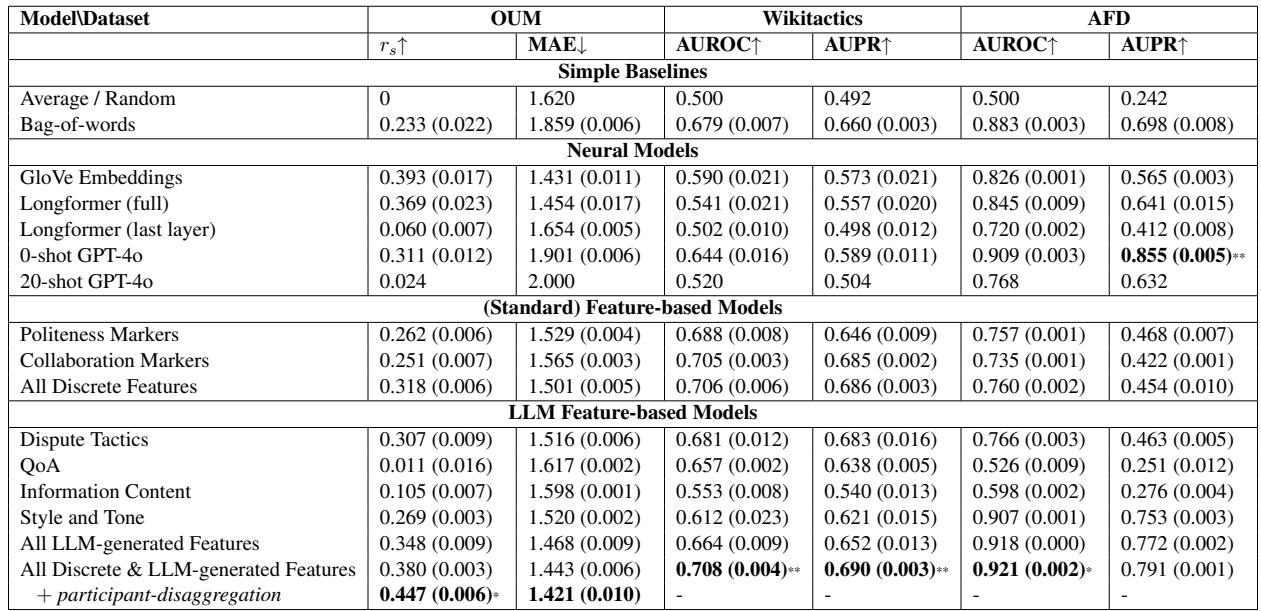

The results were surprising. In the era of Deep Learning dominance, one might expect the massive neural networks to crush the simpler regression models. That didn’t happen.

Look at the “LLM Feature-based Models” section at the bottom of Table 4.

- Wikitactics: The combined model (All Discrete & LLM-generated Features) achieves an AUROC of 0.708, significantly outperforming the best neural model (GloVe at 0.590) and even GPT-4o (0.644).

- OUM: The feature-based model achieves a correlation (\(r_s\)) of 0.380, which is comparable to the best neural baselines. When they added participant-level aggregation, it jumped to 0.447, beating everything else.

- AFD: The model performed comparably to GPT-4o zero-shot.

Key Takeaway: You don’t need a black box to get state-of-the-art results. A simple regression model, fed with high-quality, LLM-extracted features, can perform as well as or better than massive end-to-end neural networks.

The “Shortcut Learning” Test

Here is the most critical part of the analysis. High accuracy is good, but robustness is better.

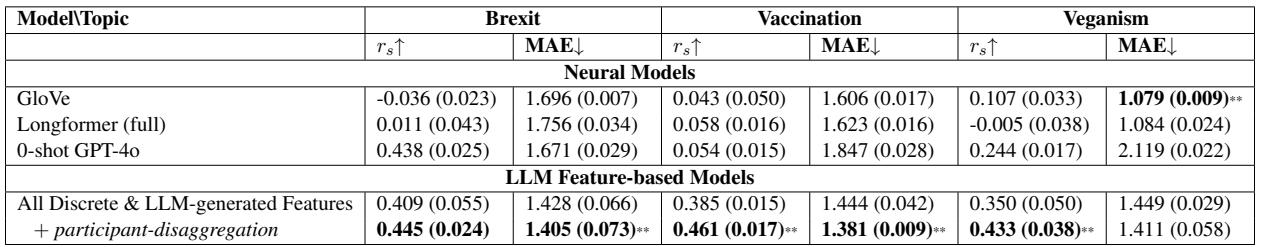

The authors hypothesized that the Neural Models (Longformer, GloVe) were “cheating”—memorizing topic-specific words rather than learning how arguments work. To test this, they took the models trained on the OUM dataset and evaluated them on specific sub-topics (Brexit vs. Vaccination vs. Veganism).

If a model truly understands “constructiveness,” it should work regardless of the topic. If it’s just looking for keywords, its performance will fluctuate wildly between topics.

Table 5 reveals the fragility of the neural models:

- GloVe & Longformer: Their performance collapses on individual topics. For Brexit, GloVe has a correlation of -0.036 (basically random guessing).

- LLM Feature-based Model: It maintains steady performance across all topics (0.409 for Brexit, 0.385 for Vaccination, 0.350 for Veganism).

This proves that the Neural Models were indeed learning shortcuts (biases) related to the topics. The LLM Feature-based framework, because it relies on linguistic features (like “politeness” or “reasoning”) rather than raw text, learned robust prediction rules that apply universally.

Explainable AI: What Actually Matters?

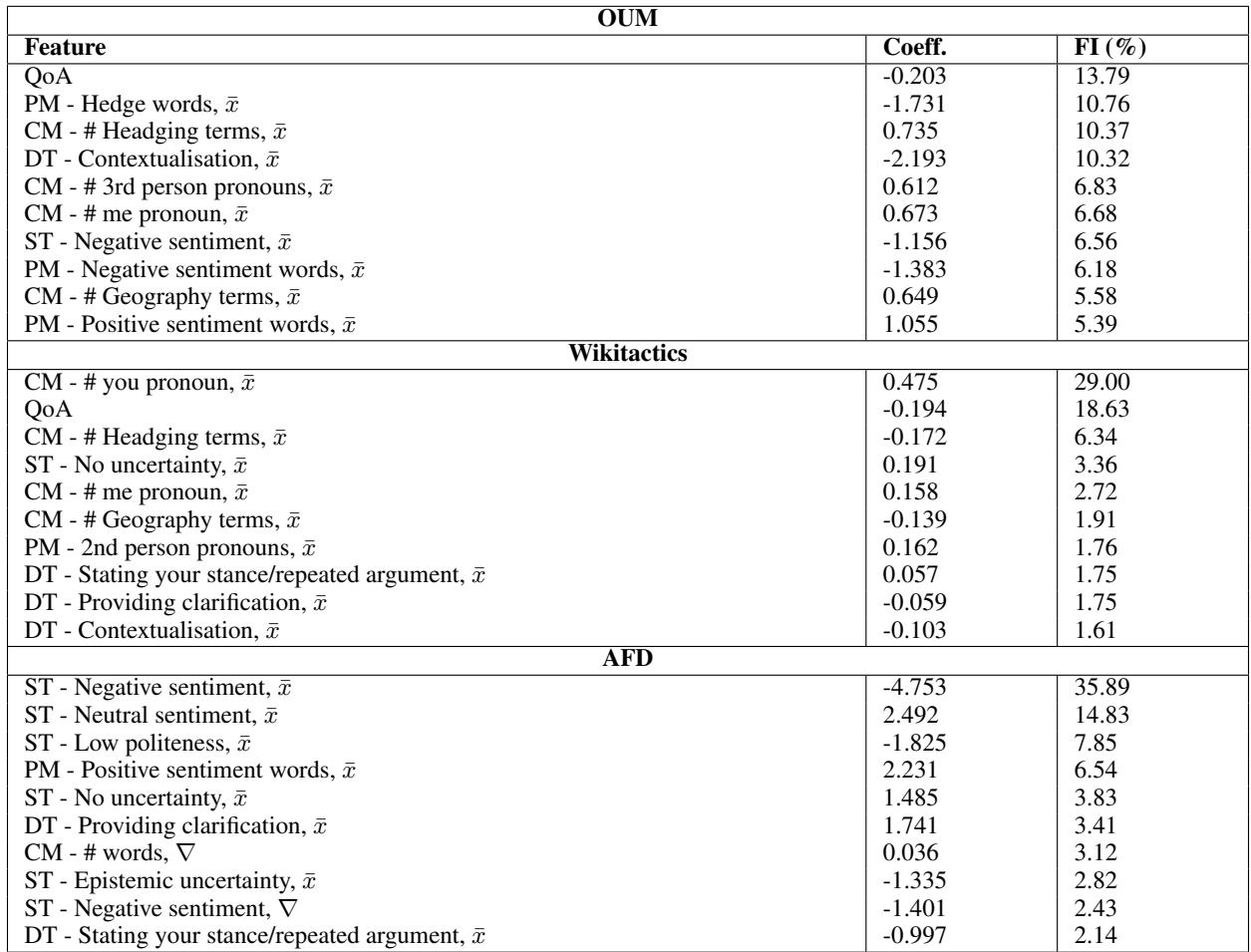

Because the researchers used interpretable regression models, they could look at the coefficients to see exactly which features drove the predictions. This gives us psychological and linguistic insights into what makes a dialogue constructive.

Here are some fascinating insights from Table 18:

1. The “You” Problem (Wikitactics)

In Wikipedia disputes, the most important feature (29% importance) was the use of second-person pronouns (“You”). The coefficient is positive for escalation. This aligns with psychological research: saying “You are wrong” feels like an attack or blame, leading to unconstructive outcomes.

2. Quality of Arguments (OUM)

For the “Opening-Up Minds” dataset, Quality of Arguments (QoA) was the top feature. Surprisingly, it had a small negative coefficient. Why? The analysis showed that high QoA scores often occurred in debates where participants were fiercely arguing back. People who simply asked questions (a “constructive” behavior) had lower QoA scores because they weren’t making arguments—they were listening. This highlights the nuance of “constructiveness”: sometimes, a high-quality debate is actually less likely to change someone’s mind than a gentle, low-stakes conversation.

3. Hedging Reduces Escalation

Across datasets, “Hedging” (using words like “possibly,” “it seems,” “I assume”) was a strong predictor of positive outcomes. It signals that the speaker is open to correction, which de-escalates conflict.

4. Sentiment on Wikipedia (AFD)

For deleting articles, Negative Sentiment was the massive driver (FI = 35%). If people are angry or negative, the article is likely to be deleted. Conversely, positive sentiment protects articles.

Conclusion

The research paper makes a compelling argument for a “middle path” in NLP. We often assume that to get better results, we need bigger, more complex neural networks. But this work shows that:

- Hybrid is Healthy: Using LLMs to extract structured features (like “Dispute Tactics”) is more robust than asking the LLM to make the final prediction.

- Interpretability isn’t Free, but it’s Cheaper Now: We no longer need armies of human annotators. LLMs can generate the expensive features for us.

- Robustness Matters: “State-of-the-art” accuracy is meaningless if the model crashes the moment the conversation topic changes. Feature-based models are naturally resistant to the topic-based biases that plague neural networks.

For students and practitioners, this framework offers a practical blueprint. If you are building systems to analyze social media, customer support, or political debate, consider stopping the “end-to-end” madness. Break the problem down into features. Use LLMs to categorize those features. And then, use a simple model to make your prediction. You’ll likely get a system that is not only accurate but one you can actually explain.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2406.14760/images/cover.png)