Social media platforms have become the de facto town squares of the 21st century. They are repositories of public opinion, offering researchers a massive dataset on how society feels about critical issues. However, for social scientists, this scale presents a paradox: the data is abundant, but understanding it at a granular level is incredibly difficult.

Take the issue of homelessness in the United States. It is a complex, sensitive topic that evokes a wide spectrum of emotions—from sympathy and calls for aid to anger and resentment. Traditional Natural Language Processing (NLP) tools, like sentiment analysis (positive vs. negative) or toxicity detection, are often too blunt for this job. A tweet criticizing the government’s housing policy might be “negative,” but it’s not necessarily “toxic.” Conversely, a tweet making a subtle, harmful stereotype about people experiencing homelessness (PEH) might slip past a toxicity filter entirely.

In a recent paper, researchers from the University of Southern California introduced a new framework called OATH-Frames (Online Attitudes Towards Homelessness). Their work does two important things: it establishes a sophisticated typology for categorizing these attitudes, and it proposes a collaborative method between human experts and Large Language Models (LLMs) to annotate data at scale.

The Limitation of Current Tools

Before diving into the solution, we must understand the problem. Why can’t we just use existing tools to analyze tweets about homelessness?

The researchers found that standard toxicity classifiers (like the Perspective API) and sentiment analysis models often mischaracterize the discourse. For example, a post might say, “You look like a homeless person.” A toxicity classifier might rate this as safe because it doesn’t use explicit slurs or threats. However, this is a Harmful Generalization—a specific type of stigmatizing language.

To truly understand public opinion, the researchers needed to move beyond “positive/negative” and map out the specific frames people use when discussing homelessness.

Step 1: Discovery and the OATH Typology

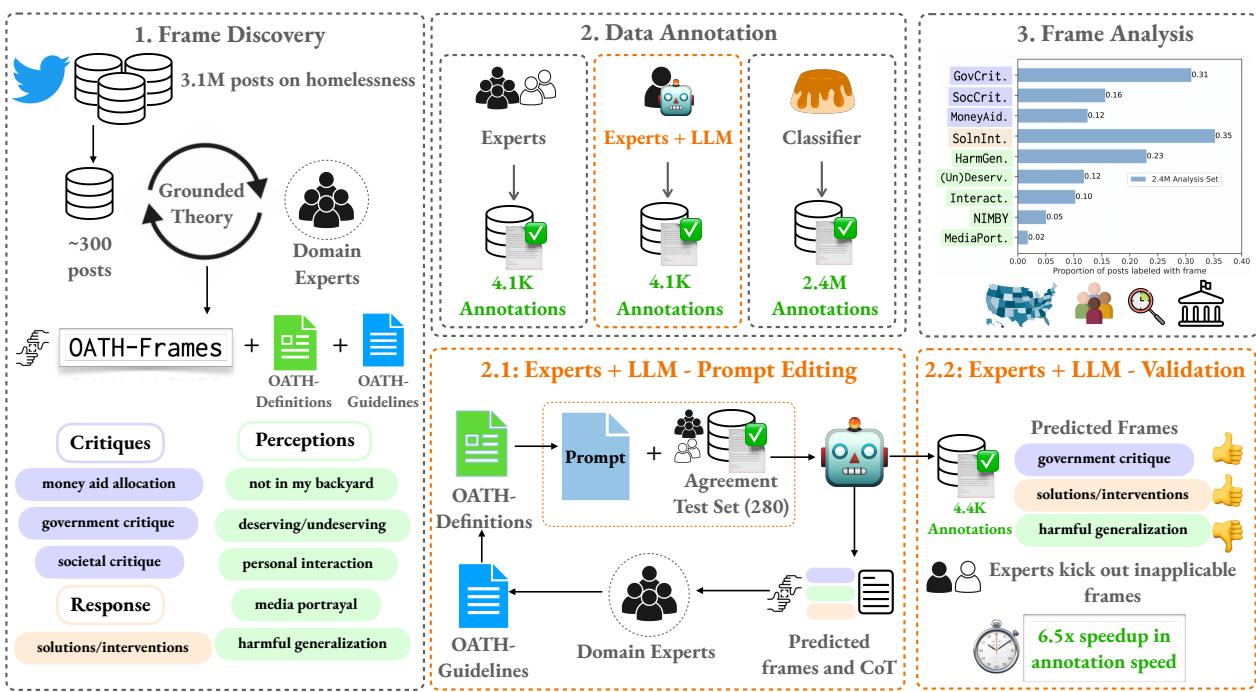

The first phase of the research involved Frame Discovery. The team collected 3.1 million tweets containing the keyword “homeless” and used a method called grounded theory. This involves expert annotators reading through samples of data to let the categories emerge organically, rather than imposing a pre-defined list.

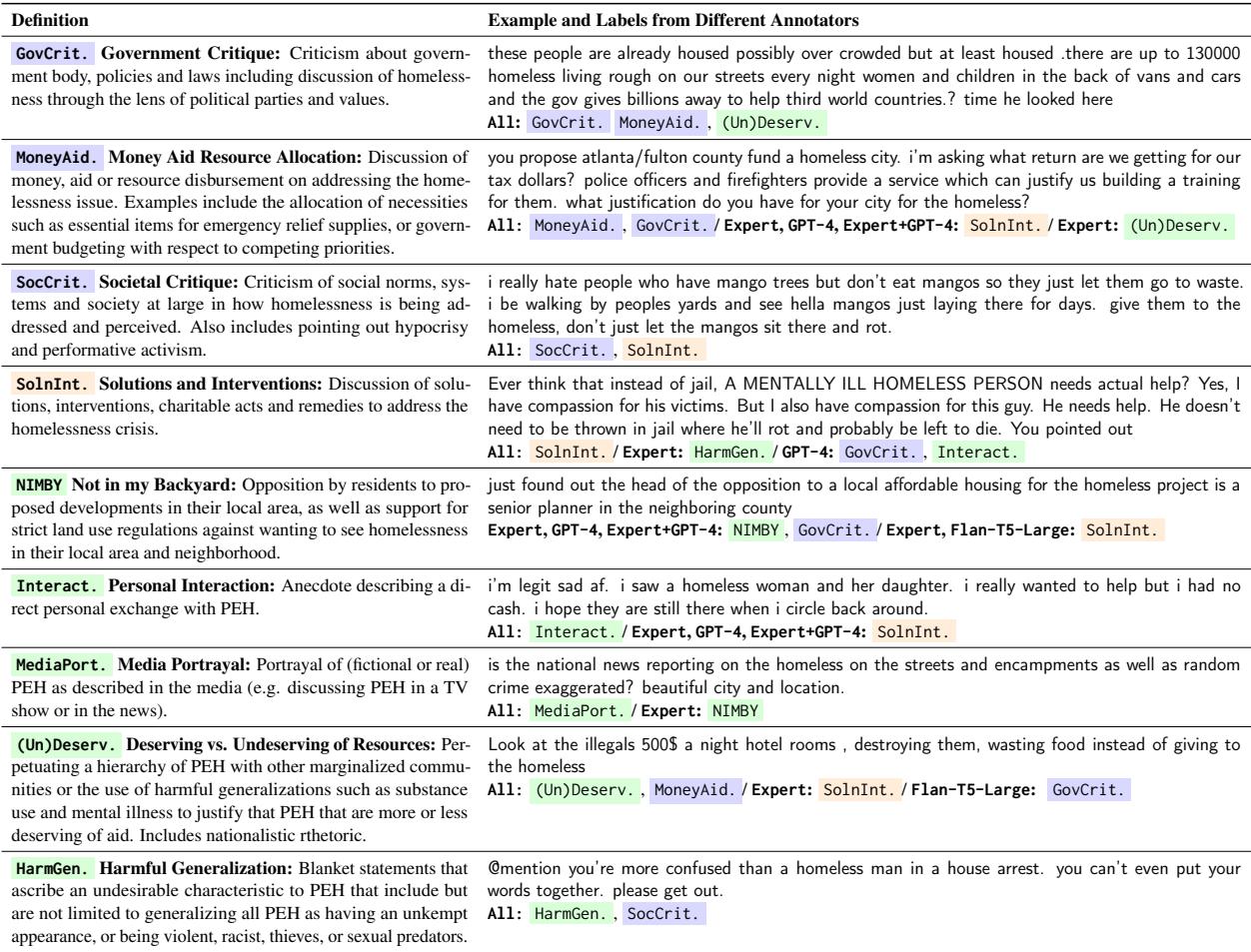

Through iterative rounds of discussion and refinement, the experts identified nine distinct “Issue-specific frames.” These frames fall under three broader themes: Critiques, Perceptions, and Responses.

As shown in the table above, the nuance here is significant:

- GovCrit (Government Critique): Blaming institutions or policies.

- NIMBY (Not In My Backyard): Opposition to housing projects in local neighborhoods.

- HarmGen (Harmful Generalization): Stereotyping PEH (e.g., associating them with crime or substance abuse).

- (Un)Deserv (Deserving vs. Undeserving): Framing the issue as a competition for resources (e.g., “Why help immigrants when we have homeless veterans?”).

This typology provides a much richer vocabulary for analyzing social discourse than simple sentiment scores.

Step 2: The Annotation Pipeline

Defining the frames is only the first step. The challenge is applying these labels to millions of posts. Human experts are accurate but slow and expensive. LLMs are fast but can be prone to “hallucinations” or missing subtle social cues.

The researchers proposed a hybrid pipeline that leverages the best of both worlds.

The process, illustrated in the figure above, follows a specific flow:

- Frame Discovery: Experts define the OATH frames.

- Expert + LLM Annotation: This is the core innovation. Instead of just letting an LLM loose on the data, or relying solely on humans, they created a collaborative loop.

- Scaling with Classifiers: The high-quality data generated by the Expert+LLM phase is then used to train a smaller, efficient model (Flan-T5-Large) to label the remaining millions of posts.

The Art of LLM-Assisted Annotation

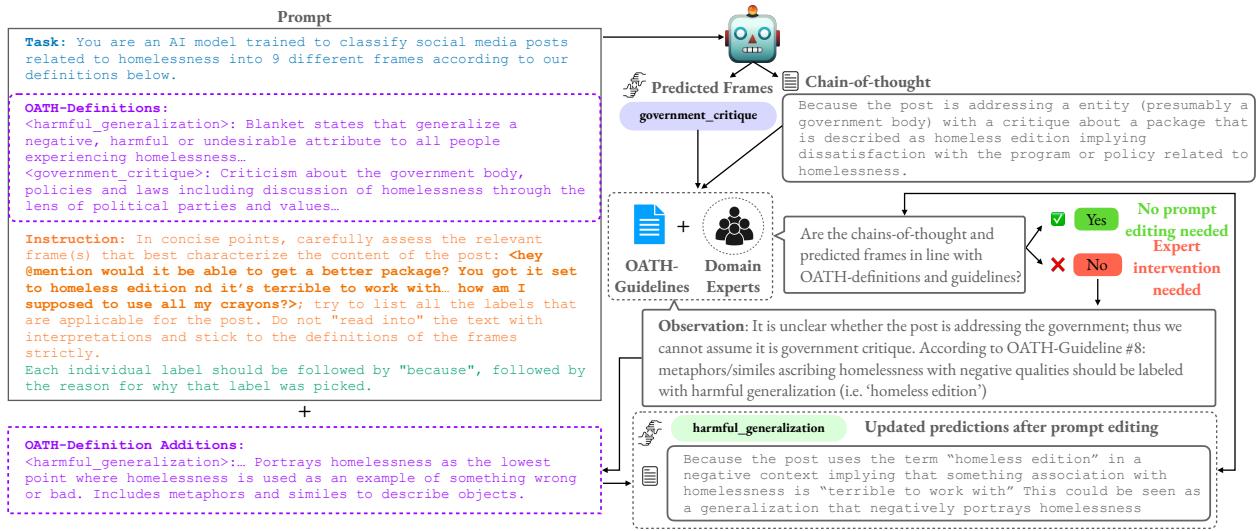

The researchers didn’t simply ask GPT-4 to “label this tweet.” They used an iterative prompt engineering strategy involving Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning.

In this setup, the LLM is asked to provide its reasoning (the “chain of thought”) before giving a final label. Human experts then review these predictions. If the LLM consistently misunderstands a definition, the experts don’t just correct the label; they refine the prompt and the guidelines based on the LLM’s reasoning errors.

Figure 3 demonstrates this feedback loop. By analyzing why the model made a mistake (e.g., confusing a metaphor for a literal statement), experts can update the OATH definitions and guidelines fed into the prompt.

The results of this collaboration were impressive. The Expert+LLM approach resulted in a 6.5x speedup in annotation time compared to humans alone. While there was a slight reduction in F1 score (a measure of accuracy) compared to purely human annotation, the efficiency gains made it possible to tackle a dataset of this magnitude.

Step 3: Analyzing 2.4 Million Posts

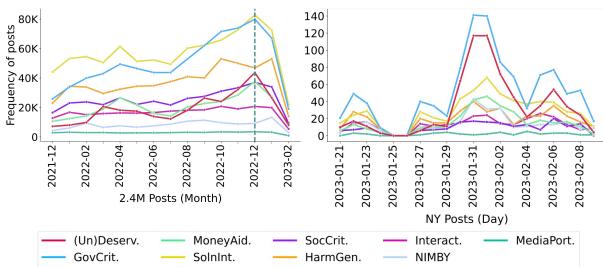

With a trained model ready, the researchers applied OATH-Frames to 2.4 million tweets spanning from 2021 to 2023. The analysis revealed trends that would have been invisible to standard analytics tools.

The Failure of Toxicity Detectors

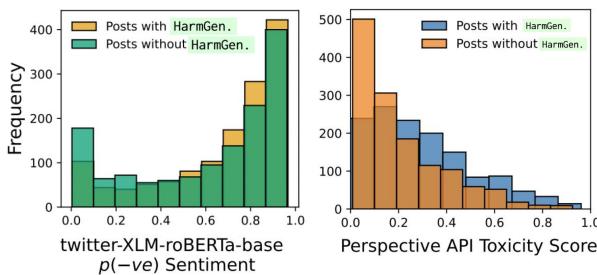

One of the most striking findings was the disconnect between OATH-Frames and standard toxicity detection.

As shown in the graph above (right side), the majority of posts labeled as HarmGen (Harmful Generalization) had very low toxicity scores (below 0.5). This confirms that existing safety tools on social media platforms are likely failing to catch stigmatizing language against vulnerable populations because the language used is often subtle or uses stereotypes rather than overt aggression.

Political Events Drive Discourse

The study also mapped how attitudes shift over time in response to real-world events.

In Figure 6 (Left), we see a significant spike in late 2022. The researchers correlated this with the U.S. Congress considering a $44.9 billion aid package for Ukraine.

This geopolitical event triggered a specific combination of frames: GovCrit (criticizing the spending) and (Un)Deserv (comparing the “deserving” homeless veterans to the “undeserving” foreign aid recipients). This highlights how homelessness is often used as a rhetorical vehicle to discuss other political issues, a nuance that a simple “negative sentiment” label would miss completely.

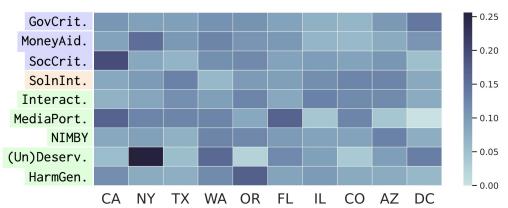

Geography of Attitudes

Finally, the researchers looked at how attitudes varied by U.S. state. They found that the discourse changes based on the local socio-economic context.

The heatmap above reveals distinct regional “fingerprints”:

- California (CA): High prevalence of HarmGen. With a large unsheltered population, the discourse often focuses on the visibility of homelessness and negative stereotypes.

- New York (NY): High prevalence of (Un)Deserv and MoneyAid. This correlates with local political clashes regarding the housing of migrants and asylum seekers, leading to discourse that pits different vulnerable groups against each other.

The researchers further supported this with regression analysis, showing that a high “Cost of Living Index” in a state correlates strongly with GovCrit—suggesting that when rent is high, people blame the government for homelessness.

Conclusion and Implications

The OATH-Frames paper offers a blueprint for the future of Computational Social Science. It demonstrates that we don’t have to choose between the deep, qualitative understanding of human experts and the massive scale of AI. By designing systems where experts guide and validate LLMs, researchers can create nuanced datasets that reflect the complexity of societal issues.

For students and practitioners in NLP and Social Work, this study highlights several key takeaways:

- Definitions Matter: You cannot analyze what you cannot define. The rigorous creation of the 9 OATH frames was just as important as the coding.

- Beyond Toxicity: We need better taxonomies to catch subtle harms like stereotyping.

- Human-in-the-Loop: The most effective AI systems for social science are those that treat LLMs as assistants to human expertise, not replacements.

By characterizing these online attitudes at scale, advocacy groups and policymakers can gain better insight into public sentiment, potentially guiding more effective communication strategies and policy reforms to help those experiencing homelessness.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2406.14883/images/cover.png)