Introduction

In the rapidly evolving world of Information Retrieval (IR), the introduction of Large Language Models (LLMs) has been a double-edged sword. On one hand, LLMs possess a remarkable ability to understand nuance, context, and intent, allowing them to rank search results with unprecedented accuracy. On the other hand, they are computationally expensive and slow.

Traditionally, when we ask an LLM to rank a list of documents (a process called listwise reranking), the model acts like a writer. It reads the documents and then generates a sequence of text output, such as “Document A is better than Document C, which is better than Document B.” This generation process is sequential and time-consuming.

But what if the model essentially “knows” the ranking the moment it starts generating? What if we could extract the entire ranking from the very first token the model predicts, rather than waiting for it to write out the whole list?

This is the premise behind FIRST (Faster Improved Re-ranking with a Single Token), a novel approach introduced by researchers from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and IBM Research. In this post, we will dissect their research paper, exploring how they managed to cut inference latency by 50% without sacrificing—and often improving—ranking performance.

Background: The Bottleneck in Neural Search

To understand the significance of FIRST, we first need to look at the current state of neural search. Modern search systems typically operate in a two-stage pipeline:

- Retriever: A fast, lightweight model (like BM25 or a dense retriever like Contriever) sifts through millions of documents to find a small set of potentially relevant candidates (e.g., the top 100).

- Reranker: A more powerful, computationally intensive model examines these top candidates and reorders them to push the most relevant ones to the top.

From Cross-Encoders to Listwise LLMs

For a long time, the “Reranker” stage was dominated by Cross-Encoders. These models take a query and a single document, process them together, and output a relevance score. While effective, they are limited because they score documents in isolation. They cannot compare Document A directly against Document B.

Enter Listwise LLM Reranking. Recent approaches, such as RankZephyr, feed the query and a list of multiple documents (e.g., 20 at a time) into an LLM. The LLM is instructed to output the document identifiers in decreasing order of relevance.

This allows the model to perform global comparisons, leading to better rankings. However, it treats the problem as a text generation task. The model must generate a sequence of tokens representing the document IDs (e.g., [Doc1] > [Doc3] > [Doc2]).

The problem? Latency. LLM generation is autoregressive—it generates one token at a time. The more documents you have, the longer the output sequence, and the slower the system becomes. Furthermore, the standard training for these models treats every error equally. If the model swaps the 1st and 2nd documents, the penalty is often the same as swapping the 19th and 20th documents, even though the former is catastrophic for search experience and the latter is negligible.

The Core Insight: The “Aha!” Moment

The researchers behind FIRST began with a hypothesis: LLM rerankers implicitly judge relevance before they explicitly generate the sequence.

When an LLM predicts the next token, it calculates a probability distribution (logits) over its entire vocabulary. If the model is about to generate the identifier for the top-ranked document, the logits for all document identifiers should ideally reflect their relative relevance.

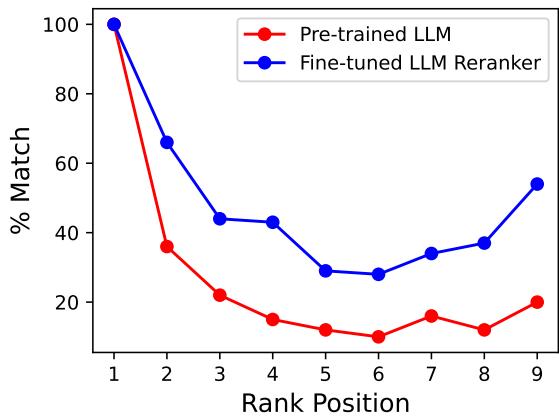

To validate this, the researchers compared a pre-trained LLM against RankZephyr (an LLM fine-tuned for ranking). They checked if the ranking implied by the logits of the first token matched the ranking of the fully generated text sequence.

As shown in Figure 2, the blue line represents RankZephyr. We can see a high degree of similarity between the ranking implied by the first token’s logits and the final generated sequence. This confirms that the model essentially “knows” the order of relevance at the very first step of generation. The sequence generation that follows is arguably redundant.

Methodology: FIRST (Faster Improved Re-ranking with a Single Token)

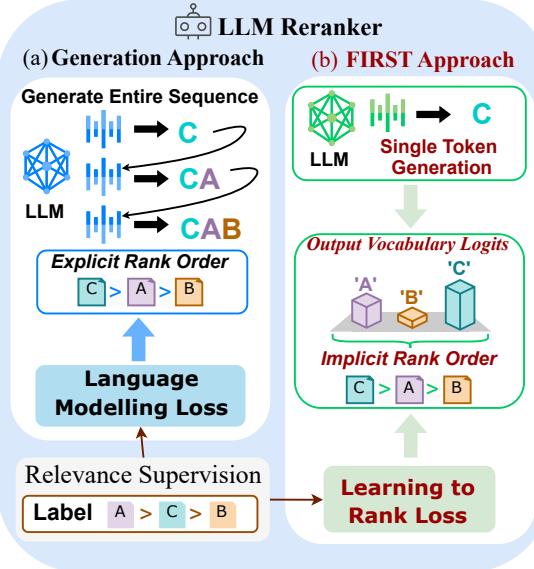

Based on this insight, the authors propose a new architecture that shifts from a “Generation Approach” to the “FIRST Approach.”

1. Single Token Decoding

The mechanism is elegant in its simplicity. Instead of asking the model to generate a string like “A > B > C,” FIRST inputs the query and documents and looks strictly at the output logits for the document identifiers (A, B, C, etc.) at the first generation step.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the Generation Approach (a) relies on the slow process of generating the full sequence. The FIRST Approach (b) halts immediately after the first pass. It extracts the logits corresponding to the document IDs (A, B, C) and sorts the documents based on these scores.

Note on Identifiers: The researchers use alphabetic identifiers (A, B, C…) rather than numbers. This is because LLM tokenizers often break multi-digit numbers (like “10” or “100”) into multiple tokens, which would complicate the single-token decoding strategy.

2. A Better Training Objective

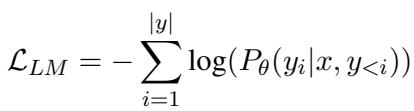

While a standard LLM can be used for FIRST inference, it isn’t optimized for it. Standard LLMs are trained with a Language Modeling (LM) objective, which minimizes the error of predicting the next token.

This standard loss (Equation 1 above) has two major flaws for ranking:

- Uniformity: It treats all positions in the sequence equally.

- Hard Targets: It usually forces the model to maximize the probability of only the correct next token, pushing all other probabilities to zero. This destroys the rich relative information we want to capture in the logits (i.e., we want the model to say A is best, but B is second best, not just “A is 100%, everything else is 0%”).

To fix this, the authors introduce a Learning-to-Rank (LTR) objective specifically designed for the logits of the first token. They use a weighted version of RankNet.

Let’s break down the equation above:

- \(s_i\) and \(s_j\): These are the output logits for document \(i\) and document \(j\).

- Log-sigmoid term: This encourages the model to give a higher score to the more relevant document (\(r_i < r_j\)).

- \(\frac{1}{i+j}\): This is the crucial weighting term. It is the inverse mean rank of the pair.

Why the weighting matters: If the model confuses the 1st document with the 2nd, \(i+j = 1+2 = 3\), so the weight is \(1/3\). If it confuses the 19th and 20th documents, the weight is \(1/39\). This means the loss function penalizes errors at the top of the list much more heavily than errors at the bottom. This aligns perfectly with search engine goals: users rarely look past the top few results.

Finally, the researchers combine the standard Language Modeling loss (to maintain the model’s linguistic capabilities) with this new Ranking loss:

The hyperparameter \(\lambda\) controls the balance between the two objectives.

Experiments and Results

The researchers fine-tuned a Zephyr-7B model using this new objective on the MS MARCO dataset and evaluated it on the comprehensive BEIR benchmark.

Does the Training Strategy Work?

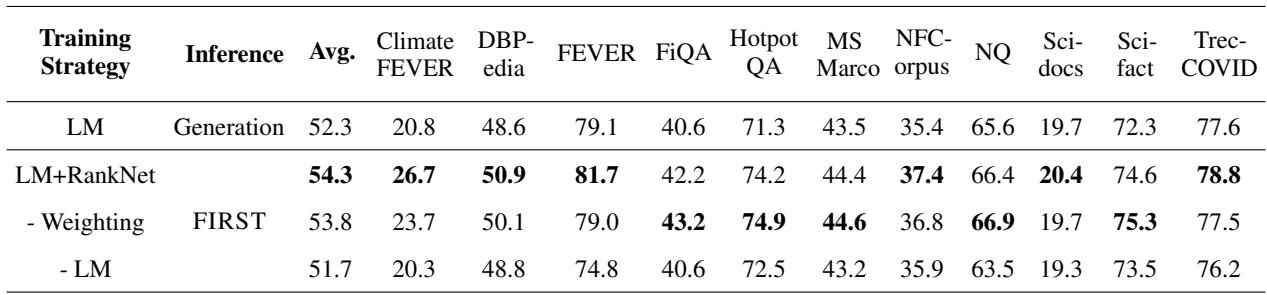

The first question is whether the new loss function actually helps. The table below compares different training strategies using nDCG@10 (a standard metric for ranking quality).

The results in Table 2 are clear:

- LM (Standard Generation): 52.3% average.

- FIRST (LM + RankNet): 54.3% average.

By adding the ranking loss, the model not only becomes compatible with single-token decoding but actually outperforms the sequence generation baseline. The ablation study also shows that the weighting mechanism (prioritizing top ranks) is essential; without it, performance drops.

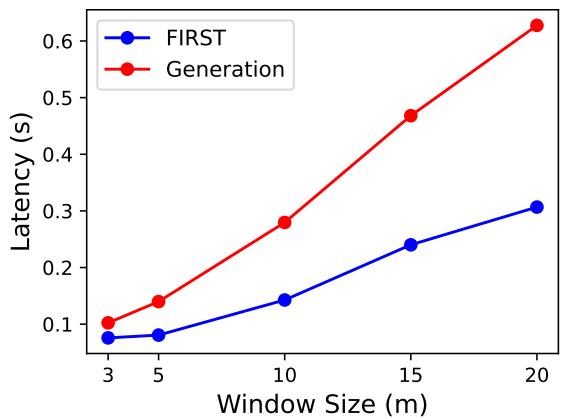

Is it Faster?

This is the primary motivation behind FIRST. Since the model generates only one token instead of a sequence of length \(N\), the latency reduction should be significant.

Figure 4 confirms this. As the window size (number of candidates) increases, the latency of the generation approach skyrockets because it has to write out more identifiers. FIRST, however, remains much flatter. The only cost increase for FIRST comes from processing a longer input prompt, not from generation.

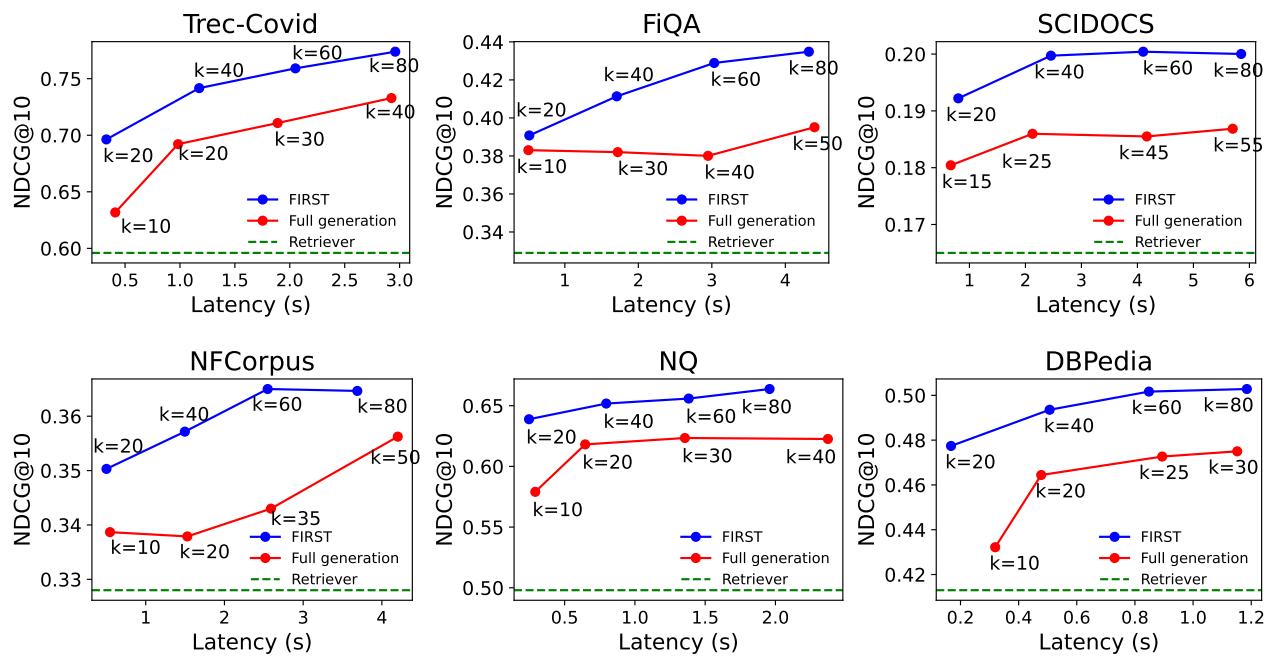

The Latency-Accuracy Trade-off

In real-world systems, we often have a “latency budget” (e.g., “return results in 200ms”). A faster model allows us to rerank more documents within the same time budget.

Figure 3 is perhaps the most compelling visualization in the paper. It plots accuracy (y-axis) against latency (x-axis).

- Blue Line (FIRST): Rises steeply and reaches high accuracy quickly.

- Red Line (Full Generation): Rises slowly.

Because FIRST is so efficient, you can rerank a larger list of candidates (increasing \(k\)) in the same amount of time it takes the standard model to rerank a small list. This results in consistently higher accuracy at any given latency threshold.

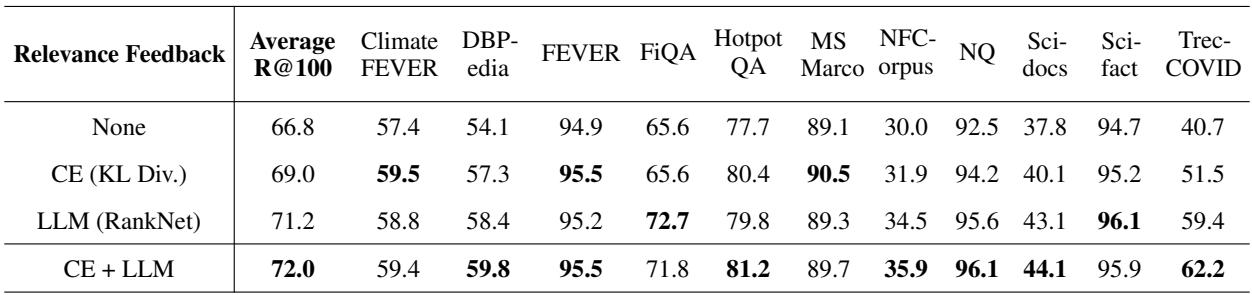

Advanced Application: Relevance Feedback

The authors explore one final, fascinating application: Relevance Feedback.

In this setup, the output of the reranker is used to “teach” or update the query vector of the initial retriever (like Contriever) during inference. The idea is to distill the intelligence of the heavy reranker back into the fast retriever to find documents that might have been missed in the first pass.

Standard methods use the scores from Cross-Encoders (CE) to do this. However, the authors found that using the ranking signals from their Listwise LLM provided much better supervision.

Table 4 shows the Recall@100 (how many relevant docs were found).

- None (Original Retriever): 66.8%

- CE Feedback: 69.0%

- LLM (FIRST) Feedback: 71.2%

- CE + LLM: 72.0%

The LLM reranker, trained with the FIRST objective, provides a stronger signal for refining the search query than traditional cross-encoders, leading to a substantial jump in recall.

Conclusion

The “FIRST” paper presents a convincing argument for rethinking how we use Large Language Models in search. By recognizing that the model’s internal state (logits) contains the ranking information long before the text is generated, the authors unlocked a 50% speed increase.

Furthermore, by moving away from generic Language Modeling losses and adopting a Learning-to-Rank objective, they proved that we can train models that care about what truly matters in search: getting the top results right.

For students and practitioners in NLP and Information Retrieval, FIRST highlights an important trend: we are moving beyond simply applying “out-of-the-box” LLMs to specific tasks. We are now opening up the black box, inspecting the logits, and designing custom loss functions to mold these powerful models into efficient, domain-specific tools.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2406.15657/images/cover.png)