When you are faced with a complex problem that requires multiple steps to solve, how do you approach it?

Psychological research suggests that humans often start with “heuristics”—mental shortcuts or shallow associations. If you are looking for your keys, you might first look on the kitchen counter simply because “keys often go there,” not because you remember putting them there. However, as you eliminate options and get closer to the solution, your thinking shifts. You become more rational, deducing exactly where you must have been last.

Do Large Language Models (LLMs) behave the same way?

We often think of LLMs as either “smart” or “hallucinating,” but recent research suggests their reasoning process is more dynamic than that. A fascinating paper titled “First Heuristic Then Rational” by researchers from Tohoku University, RIKEN, and MBZUAI investigates this very question.

Their findings reveal a systematic strategy in how models like GPT-4 and PaLM2 reason: they rely heavily on lazy shortcuts in the early stages of a problem, but switch to rational, logic-based reasoning as they get closer to the answer.

In this post, we will break down their methodology, the concept of “reasoning distance,” and what this means for the future of AI.

The Problem with Multi-Step Reasoning

Multi-step reasoning is the holy grail of current AI development. Techniques like “Chain-of-Thought” (CoT) prompting—where the model is asked to “think step-by-step”—have significantly improved performance. However, models still frequently fail on tasks that require long chains of logic. They often get distracted by irrelevant information or superficial patterns.

The researchers hypothesized that this failure isn’t random. They proposed that LLMs have a limited “lookahead” capacity. When the path to the solution is long and the goal is distant, the model cannot effectively plan the whole route. So, it panics and grabs the nearest heuristic (a shortcut). As the reasoning progresses and the distance to the goal shrinks, the model “wakes up” and begins to act rationally.

Defining the Heuristics

To test this, the researchers focused on three specific types of heuristics—superficial biases that often trick models:

- Lexical Overlap (OVERLAP): The tendency to select information simply because it shares words with the question. If the question asks about “Judy,” the model might grab a sentence about “Judy’s mother,” even if it’s irrelevant.

- Position Bias (POSITION): The tendency to focus on information based on where it appears in the text, such as the very first sentence.

- Negation (NEGATIVE): A bias related to how models process (or avoid) negative words like “not.”

The researchers wanted to see if models would fall for these traps more often at the start of a reasoning chain than at the end.

The Experimental Setup: Arithmetic Reasoning

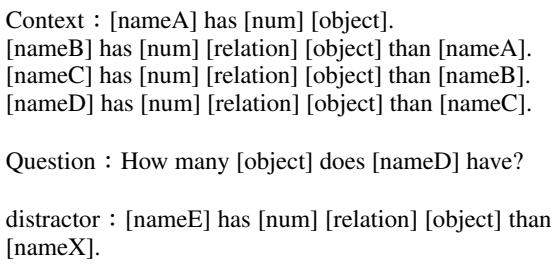

To measure this phenomenon rigorously, the team used arithmetic reasoning tasks. These are logic puzzles where you must track variables (like the number of apples people have) across several statements to answer a final question.

They utilized two datasets:

- GSM8K: A standard dataset of grade-school math word problems.

- Artificial Controlled Data: A custom-generated dataset that allows for precise control over the logic chain.

Understanding the “Distance” (\(d\))

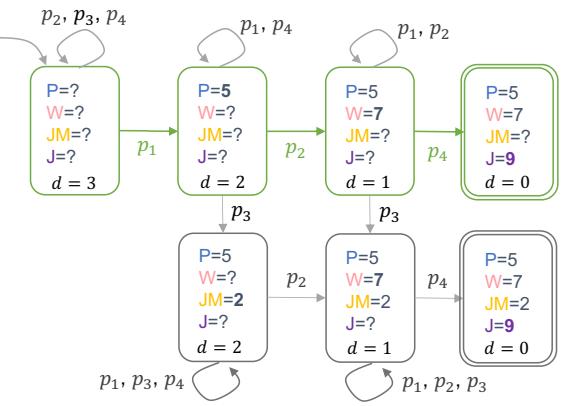

The core innovation of this paper is the concept of distance (\(d\)). In a step-by-step solution, \(d\) represents the number of remaining steps required to reach the answer.

- High \(d\) (e.g., \(d=4\)): You are at the beginning of the problem. The answer is far away.

- Low \(d\) (e.g., \(d=1\)): You are almost there. One more step and you solve it.

The researchers modeled the reasoning process as a graph search. At each step, the model looks at the available premises (\(P\)) and paraphrases or combines them to create a new fact (\(z\)).

As shown in Figure 2 above, the model starts with a set of facts (left). As it selects the correct premises (the green path), the state of knowledge changes, and the distance (\(d\)) to the goal decreases. The researchers wanted to know: At which value of \(d\) does the model step off the green path and follow a red, heuristic path?

The Trap: Distractors

To test the models, the researchers injected distractors into the problems. A distractor is a fake premise that looks relevant based on heuristics but is actually useless for solving the problem.

For example, they might construct a problem where the correct next step involves “Peggy,” but they insert a distracting sentence about “Peggy” that matches the Overlap heuristic.

If the model chooses the distractor, it is “thinking heuristically.” If it chooses the correct premise despite the distractor, it is “thinking rationally.”

Phase 1: Do Models Use Heuristics?

First, the researchers simply established whether models are susceptible to these distractors at all. They tested four models: PaLM2, Llama2-13B, GPT-3.5, and GPT-4.

The results were clear: Yes, they do.

When distractors were added, the models frequently picked them up. For instance, in the Overlap condition (where a useless sentence shared a name with the question), models like PaLM2 and Llama2 picked the wrong sentence significantly more often than in a baseline random control. Even GPT-3.5 showed a high susceptibility.

Interestingly, GPT-4 was the most robust, showing very low reliance on heuristics compared to the others. It seems that as models get larger and more advanced, they naturally become more rational. However, the bias wasn’t zero.

Phase 2: The Dynamic Shift (The Core Discovery)

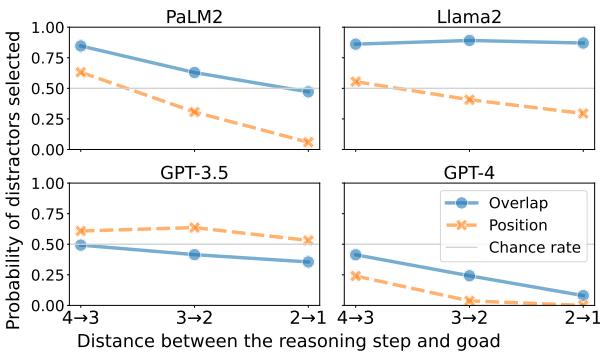

This is the most critical part of the study. The researchers analyzed when the distractors were selected. They plotted the probability of selecting a distractor against the distance to the goal (\(d\)).

The Hypothesis: The curve should be downward sloping. High error rate at high \(d\), low error rate at low \(d\).

The Results:

Figure 3 above tells the story beautifully. Look at the graphs for PaLM2 and GPT-4 specifically:

- The X-Axis (\(d\)): Represents the reasoning progress. The far left (\(4 \to 3\)) is the start of the problem. The right (\(2 \to 1\)) is near the end.

- The Y-Axis: The probability of falling for the trap (selecting the distractor).

Observations:

- PaLM2 (Top Left): Look at the solid line with circle markers (Overlap). At the start of the problem (\(d=4 \to 3\)), the probability of picking the distractor is nearly 90%. The model is almost guaranteed to take the shortcut. But as the reasoning progresses to the final steps (\(d=2 \to 1\)), the probability drops significantly.

- GPT-4 (Bottom Right): While GPT-4 is much smarter overall, it exhibits the exact same shape. At the start, it has a moderate chance of being distracted. By the end, the error rate drops to nearly zero.

This confirms the “First Heuristic, Then Rational” theory. When the model looks at a problem and sees a long road ahead, it cannot compute the full path. Lacking a plan, it falls back on simple text matching (heuristics). Once it stumbles closer to the solution—perhaps by luck or because the heuristic pointed in the vague general direction—the “computational load” of the remaining path becomes manageable, and the model switches to strict logic.

Visualizing the Volume of Reasoning

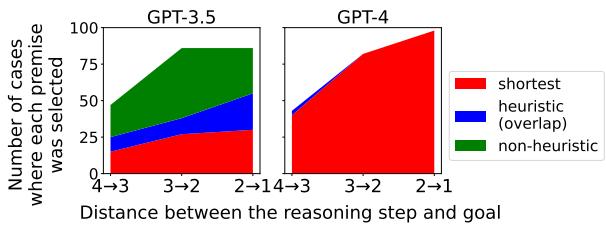

The researchers also visualized this by counting the raw number of times premises were selected.

In Figure 4, we see the breakdown for the Overlap heuristic:

- Red Area: The model chose the correct, rational step (Shortest Path).

- Blue Area: The model chose the heuristic distractor.

For GPT-3.5 (Left), notice how the Red area is small at the beginning (left side of the chart) and grows larger toward the right. The model literally becomes more “correct” as it gets closer to the answer. For GPT-4 (Right), the Red area dominates, proving its superior reasoning capabilities, but the small slivers of other colors still appear mostly at the beginning.

Why Does This Happen?

The paper posits that this behavior is similar to a bounded lookahead in search algorithms.

Imagine you are playing Chess. If you are a Grandmaster, you can see 15 moves ahead. If you are a beginner, you can maybe see 2 moves ahead.

- When the game is complex (early game), the beginner can’t calculate the win. They just make moves that “look good” (controlling the center, protecting pieces)—these are heuristics.

- When the game is nearly over (endgame) and there are only a few pieces left, even the beginner can calculate the “mate in 2” perfectly. They become rational.

LLMs appear to function like the beginner chess player. They have a limited “contextual buffer” for future planning. When the reasoning chain exceeds that buffer, they revert to surface-level patterns found in their training data (like “words usually appear near similar words”).

Conclusion and Implications

The “First Heuristic Then Rational” strategy highlights a fundamental limitation in current Large Language Models. While they can perform impressive logical feats, their ability to plan over long horizons is fragile. They are not consistently rational agents; they are dynamic agents that oscillate between laziness and logic depending on the complexity of the current step.

Key Takeaways:

- Dynamic Strategy: LLMs do not use a single strategy. They switch gears from heuristic to rational as the goal comes into view.

- Distance Matters: The further away the solution is, the more likely the model is to hallucinate or be distracted by irrelevant keywords.

- Model Evolution: Larger, stronger models (like GPT-4) rely less on heuristics, suggesting that scaling up models improves their “lookahead” capacity.

For students and engineers working with LLMs, this suggests that prompt engineering techniques that break problems down are vital. By forcing the model to solve smaller sub-problems, we effectively reduce the “distance” \(d\) for each individual step, keeping the model in its rational “green zone” and preventing it from falling back on lazy heuristics.

The transition from heuristic to rational thinking is a deeply human trait. It turns out, our AI models might be a little more like us than we thought—prone to taking shortcuts until the deadline is right in front of them.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2406.16078/images/cover.png)