Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 and Qwen have revolutionized how we interact with text. They can write poetry, generate code, and summarize complex documents. Yet, there is a specific, seemingly simple task where these giants often stumble: Chinese Spell Checking (CSC).

It seems counterintuitive. How can a model capable of passing the Bar Exam fail to correct a simple homophone error in a Chinese sentence?

In this deep dive, we are exploring a fascinating research paper, “C-LLM: Learn to Check Chinese Spelling Errors Character by Character.” We will uncover why the standard architecture of modern LLMs creates a fundamental bottleneck for spelling correction and how a new method, C-LLM, proposes a structural shift—changing how the model “sees” text—to achieve state-of-the-art results.

If you are a student of NLP or computer science, this analysis will take you through the journey from problem formulation to tokenization mechanics, and finally to a novel solution that outperforms existing benchmarks.

The Paradox of LLMs in Spell Checking

Chinese Spell Checking (CSC) is a task with very specific constraints. Unlike grammatical error correction, which might involve rewriting whole phrases, CSC usually involves detecting and correcting individual erroneous characters.

The task generally adheres to two strict rules:

- Equal Length Constraint: The corrected sentence must have the exact same number of characters as the source sentence.

- Phonetic Constraint: Approximately 83% of Chinese spelling errors are homophones or phonetically similar characters (e.g., typing “dà” instead of a different “dà”).

Why Do General LLMs Fail Here?

You might expect an LLM to excel at this via few-shot prompting. However, researchers found that models like GPT-4 often hallucinate changes that violate these constraints.

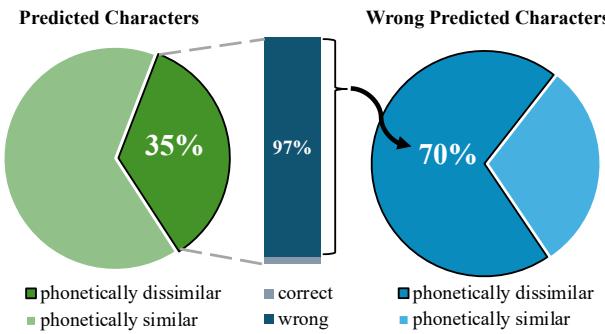

When tested, GPT-4 produced output where 10% of predicted sentences did not match the source length. Even worse, 35% of the predicted characters were phonetically dissimilar to the original characters. This means the model wasn’t just correcting spelling; it was often rewriting the sentence entirely or guessing characters that sounded nothing like the original.

As shown in Figure 2, a massive chunk of the model’s errors comes from these phonetically dissimilar predictions (the blue section). If a model guesses a character that sounds completely different, it’s not performing “spell check”—it’s performing semantic rewriting, which is not what we want.

The researchers identified that the root cause isn’t the model’s intelligence—it’s the tokenization.

The Root Cause: Mixed Character-Word Tokenization

To understand C-LLM, we first need to understand how standard LLMs consume text. Modern models use Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) or similar sub-word tokenization strategies. This is efficient because it groups common characters into single tokens (words).

For example, in English, “unbelievable” might be one token. In Chinese, common multi-character words like “胆量” (courage/guts) or “图片” (picture) are grouped into single tokens.

The Alignment Problem

This grouping creates a “Mixed Character-Word” scenario that destroys the one-to-one mapping required for CSC.

Let’s look at a concrete example provided by the researchers.

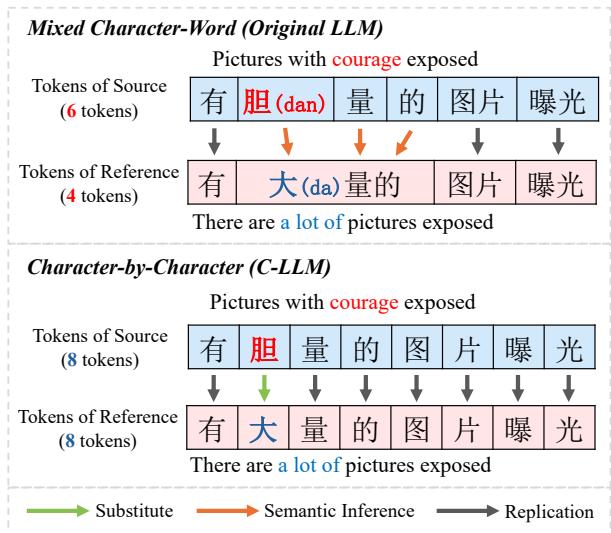

In the top half of Figure 1, we see the “Original LLM” approach.

- Source: The input contains the characters “有 胆量 的…” (Has courage…).

- Reference (Target): The correction should be “有 大量 的…” (Has [a] large amount of…).

Here is the problem: The tokenizer sees “胆量” (dǎn liàng) as one token. But the correction requires changing “胆” to “大” (dà). The model effectively has to:

- Take the token “胆量”.

- Internally break it down into “胆” and “量”.

- Realize “胆” is wrong.

- Find a new word “大量” (Large amount) or a combination of tokens “大” and “量” to replace it.

This complex reasoning requires the model to infer implicit alignments. It cannot simply say “Replace Character 2 with Character X.”

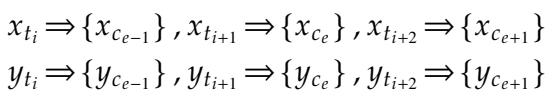

The Mathematical View of Misalignment

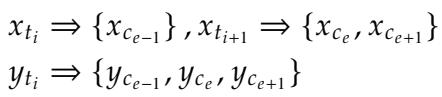

We can formalize this misalignment. Let \(x_t\) be the source tokens and \(y_t\) be the reference (corrected) tokens.

In a standard LLM, one source token might map to multiple characters, or multiple tokens might merge into one word.

In the equation above:

- \(x_{t_{i+1}}\) is a single token containing two characters \(\{x_{c_e}, x_{c_{e+1}}\}\).

- The target \(y_{t_i}\) groups three characters together.

This creates a “many-to-one” or “one-to-many” mapping problem. The model struggles to learn the Equal Length Constraint because the number of tokens changes even if the number of characters should stay the same.

Even in the scenario above, where the token count matches, the boundaries of the tokens might shift, confusing the phonetic mapping. The model essentially loses track of which specific character sounds like which other character.

The Solution: C-LLM (Character-by-Character)

To fix this, the researchers propose C-LLM. The core idea is elegant in its simplicity: Force the LLM to process text Character-by-Character.

If the model reads one character at a time, the CSC task simplifies from a complex reasoning problem to a straightforward sequence labeling task: “Copy this character, copy that character, replace this one.”

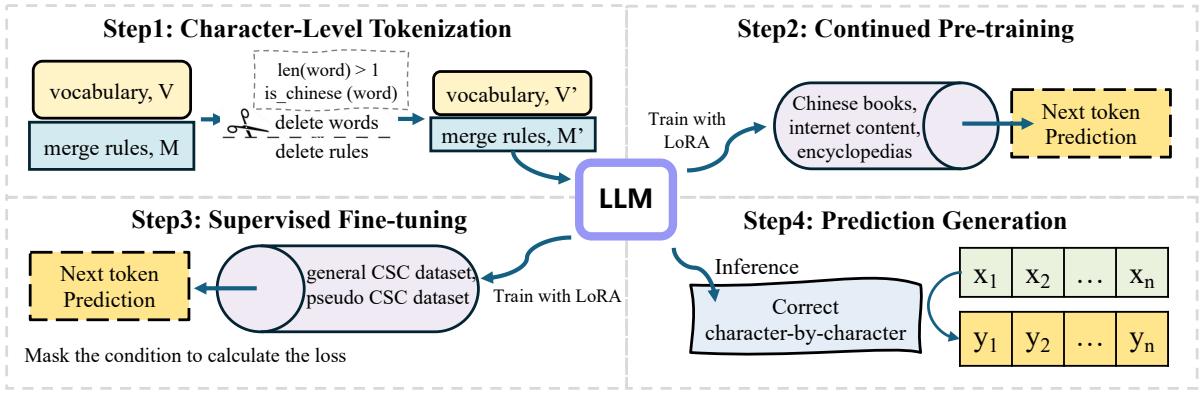

Here is the overview of the C-LLM pipeline:

The methodology consists of three distinct phases:

- Character-Level Tokenization

- Continued Pre-training

- Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT)

Let’s break these down.

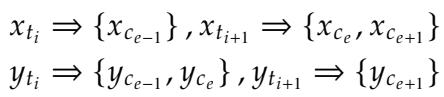

Step 1: Character-Level Tokenization

The first step is to modify the model’s vocabulary. The researchers took the standard vocabulary (from QWEN, in this experiment) and filtered it.

They removed any token that represented a multi-character Chinese word. They adjusted the merge rules to ensure that any Chinese string would be split into individual characters.

The result is a clean, one-to-one alignment:

As seen in the equation above, every source token \(x_{t_i}\) corresponds to exactly one character, and exactly one target token \(y_{t_i}\). This explicitly enforces the length constraint at the architectural level.

Step 2: Continued Pre-training

You cannot simply change a tokenizer and expect the model to work. The model was trained to understand “words.” By chopping everything into characters, we have effectively disrupted its internal language model—its “perplexity” (a measure of how surprised a model is by text) skyrockets.

To fix this, the researchers perform Continued Pre-training. They take the model with the new character-only vocabulary and train it on a massive corpus of general Chinese text (books, encyclopedias, internet content).

This step allows the model to adapt to the new granular input. As noted in the paper, before this step, the perplexity was very high (meaning the model was confused). After pre-training, the perplexity dropped back down to levels comparable to the original model.

Step 3: Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT)

Finally, the model is taught the specific task of spell checking. The researchers used LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation), a parameter-efficient fine-tuning method.

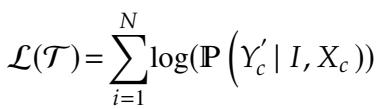

The loss function used is standard for generative models:

The model is fed pairs of (Input Sentence with Errors, Corrected Sentence) and learns to predict the correct sequence. Because of Step 1, this learning process is now much easier for the model: it mostly just learns to “copy” tokens, only activating its “correction” logic when it detects a phonetic or visual mismatch.

Experimental Results

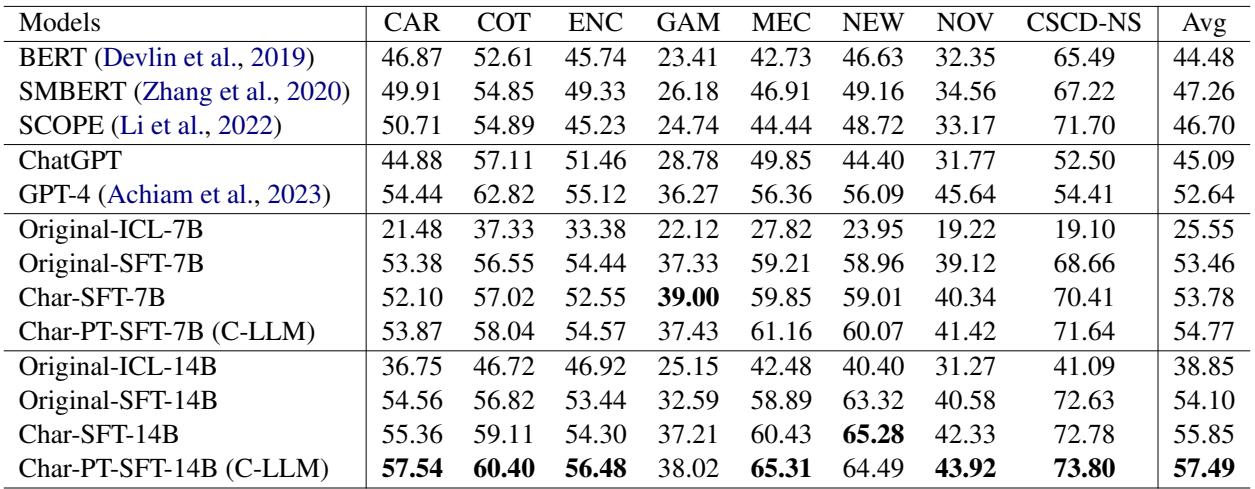

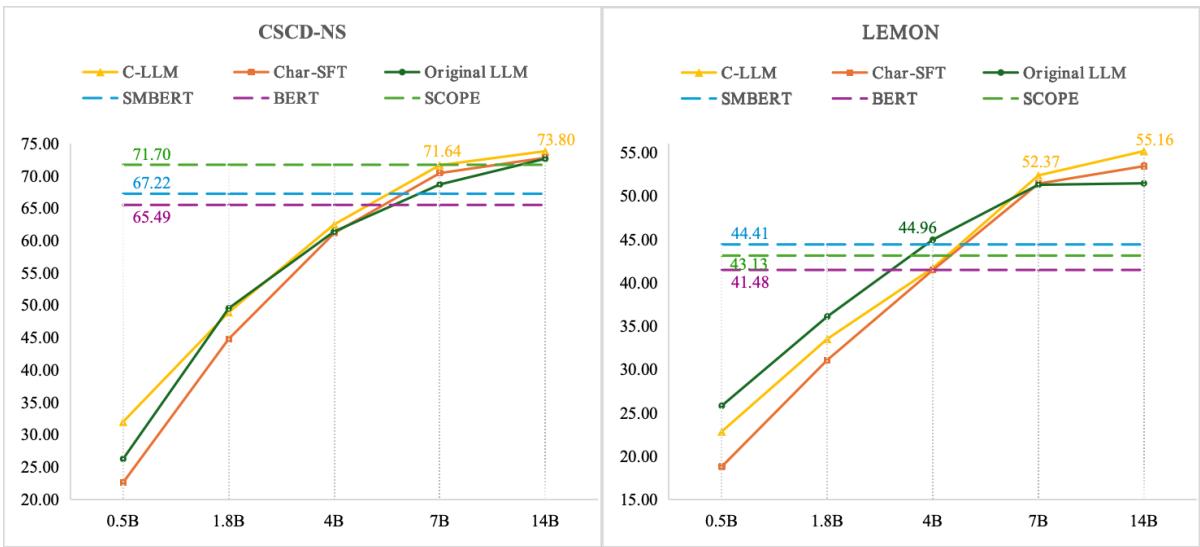

The researchers evaluated C-LLM on two major benchmarks: CSCD-NS (general spelling errors) and LEMON (a difficult, multi-domain dataset covering medical, gaming, car, and news domains).

They compared C-LLM against:

- BERT-style models: The previous state-of-the-art (e.g., PLOME, SCOPE).

- Original LLMs: QWEN, ChatGPT, and GPT-4 using standard tokenization.

Performance Comparison

The results were decisive. C-LLM significantly outperformed both the BERT-based models and the standard LLMs.

In Table 3, look at the Avg column on the far right:

- BERT-style models averaged between 44% and 47% F1 score.

- GPT-4 achieved 52.64%.

- Original QWEN (14B) achieved 54.10%.

- C-LLM (14B) achieved 57.49%, setting a new state-of-the-art.

The improvement is even more drastic in specific verticals. For example, in the Car (CAR) and Medical (MEC) domains, C-LLM showed substantial gains over the baselines.

Scaling Trends

One of the most important questions in modern AI is: “Does it scale?” If we make the model bigger, does this method still help?

Figure 4 shows the scaling trends. The Red Line represents C-LLM.

- On the left graph (CSCD-NS dataset), C-LLM consistently stays on top as the model size grows from 0.5B to 14B parameters.

- The gap between C-LLM and the “Original LLM” (Blue Line) suggests that the character-level approach unlocks performance that raw parameter count alone cannot easily achieve.

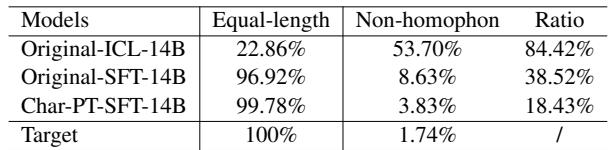

Analyzing the “Why”: Length and Phonetics

Did the method actually solve the specific constraints we discussed in the introduction?

Table 4 confirms the hypothesis:

- Equal-length: The original model only maintained the correct sentence length 96.92% of the time. C-LLM boosted this to 99.78%—almost perfect.

- Non-homophonic Errors: The original model made “random” guesses (non-phonetic errors) 8.63% of the time. C-LLM reduced this to 3.83%.

This proves that by forcing the model to operate character-by-character, it became much more “conservative” and precise, adhering to the strict rules of Chinese spelling.

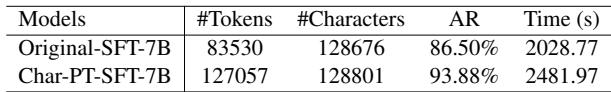

The Trade-Off: Inference Speed

No method is perfect. By splitting words into individual characters, the sequence length of the text increases. Since LLMs generate output one token at a time, generating a sentence character-by-character takes longer than generating it word-by-word.

As shown in Table 5, the number of tokens (#Tokens) increased from 83k to 127k for the test set. Consequently, the inference time increased by approximately 22%.

However, the authors note an interesting side effect: the Acceptance Rate (AR) for speculative decoding increased. Because the task is simpler (mostly copying characters), “Draft Models” (smaller models used to speed up generation) are much more accurate at guessing the next token, which helps mitigate some of the speed loss.

Conclusion

The paper “C-LLM: Learn to Check Chinese Spelling Errors Character by Character” provides a compelling lesson in architectural design. It reminds us that “bigger is not always better”—sometimes, “structural alignment” is better.

Standard LLMs, despite their reasoning power, are handicapped in Chinese Spell Checking because their tokenizer abstracts away the very unit (the character) that needs correcting. By reverting to a simpler, character-level view, C-LLM aligns the model’s perception with the task’s reality.

Key Takeaways:

- Granularity Matters: Tokenization isn’t just a preprocessing step; it fundamentally defines what the model can easily manipulate.

- Constraints are Key: CSC is difficult because of length and phonetic constraints. Character-level tokens enforce the length constraint naturally.

- Adaptability: We can retrofit powerful general-purpose LLMs to specific granularities through continued pre-training and fine-tuning.

For students and researchers, C-LLM serves as a great example of how analyzing the specific errors of a model (like the phonetic mismatch in Figure 2) can lead to a targeted, architectural solution that advances the state of the art.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2406.16536/images/cover.png)