In the rapidly evolving world of Artificial Intelligence, we are often told that “transparency” is the key to trust. As models become more complex—evolving into the “black boxes” of Deep Learning—users, developers, and regulators alike are demanding to know why an AI made a specific decision. This demand has given rise to the field of Explainable AI (XAI). The prevailing assumption is simple: if an AI can explain its reasoning, users can better understand its capabilities and, crucially, identify its limitations.

But what if explanations do the exact opposite? What if a well-worded explanation masks an AI’s failure, tricking the user into thinking the system is smarter than it actually is?

A fascinating research paper titled “The Illusion of Competence” by Sieker et al. tackles this question head-on. By designing a clever experiment involving Visual Question Answering (VQA) systems, the researchers tested whether explanations help users diagnose a fundamental flaw in an AI’s vision, or if they merely act as a polished veneer over a broken system. For students of machine learning and human-computer interaction, this paper serves as a critical warning: plausible explanations does not equal faithful reasoning.

The Problem: Black Boxes and Mental Models

Before diving into the experiment, we must understand the cognitive gap XAI tries to fill. When humans interact with a system, they form a mental model—an internal representation of how that system works, what it can do, and what it cannot do.

If you drive a car and the engine creates a high-pitched whine when you accelerate, you update your mental model: “The transmission might be slipping.” You now know the car has a limitation. In AI, however, the “engine” is a neural network with billions of parameters. When an AI makes a mistake, it is rarely obvious why.

The goal of XAI is to provide evidence that allows users to build an accurate mental model. If an AI classifies a Husky as a Wolf, and the explanation highlights the snow in the background, the user correctly diagnoses the flaw: “The AI is relying on the background, not the animal’s features.”

The researchers behind this paper argue that we need to distinguish between two types of explanation quality:

- Faithfulness: Does the explanation accurately reflect the model’s internal reasoning?

- Plausibility: Does the explanation sound convincing and logical to a human?

The danger arises when an explanation is highly plausible (it sounds right) but not faithful (it doesn’t reflect the system’s actual broken process). This discrepancy can lead users to build a dysfunctional mental model, leading to unwarranted trust.

The Experimental Setup: Inducing “Colorblindness”

To test whether explanations help users spot errors, the researchers needed a controlled environment where the AI had a specific, undeniable limitation. They chose the domain of Visual Question Answering (VQA). In this task, an AI is given an image and a question (e.g., “What color is the bus?”), and it must generate an answer.

However, modern AI is often too good. To test user perception of limitations, the researchers had to artificially break the AI. They did this through a manipulation of the visual input.

The Manipulation

The researchers set up two pipelines for the AI models:

- Full Color: The AI sees the original image.

- Grayscale: The AI sees a black-and-white version of the image.

Here is the catch: The human participants always saw the full-color image.

This setup created a perfect trap. If the AI is shown a grayscale image of a red ball and asked “What color is the ball?”, it physically cannot “see” the redness. If it answers correctly, it is likely guessing based on context or bias (e.g., knowing that fire trucks are usually red). If it answers incorrectly, the user should ideally be able to look at the explanation and realize, “Oh, the AI didn’t perceive the color.”

The researchers used two datasets:

- VQA-X: Real-world images from the COCO dataset.

- CLEVR-X: Synthetic images of geometric shapes (cylinders, cubes, spheres) where properties like color, shape, and material are strictly defined.

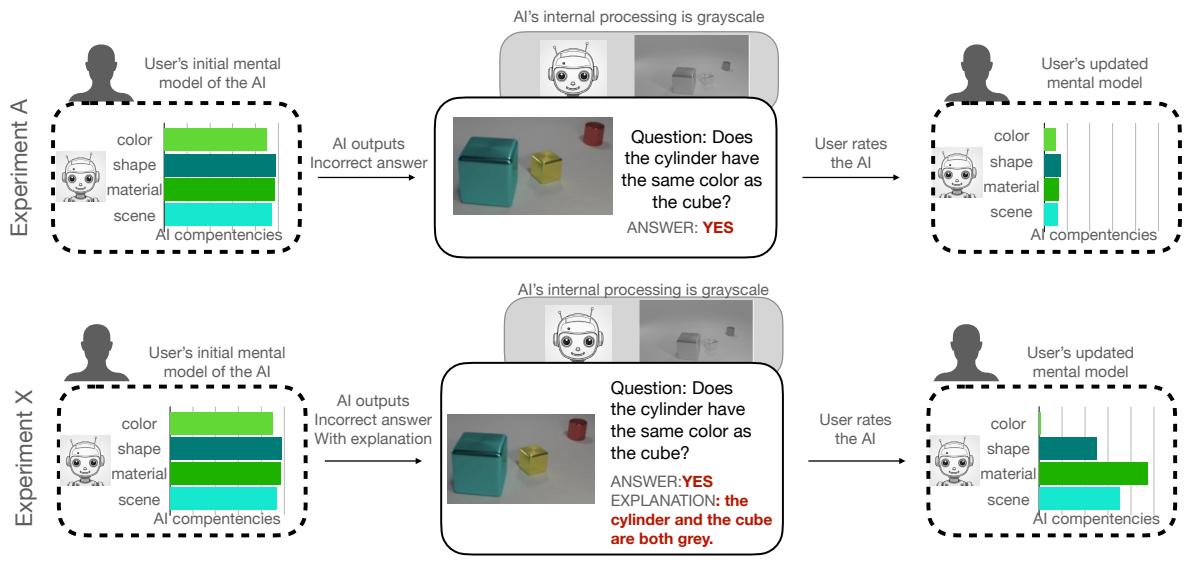

As shown in Figure 1, the models generate natural language explanations. Look closely at the top example (VQA-X). The user asks, “What season is it?”

- Color Input: The AI says “Summer” because the grass is green.

- Grayscale Input: The AI effectively hallucinates. It might guess correctly or incorrectly, but its reasoning cannot be based on the green grass because it only received grayscale pixel data.

In the bottom example (CLEVR-X), the grayscale model attempts to answer a question about “yellow shiny objects.” Despite not seeing yellow, it constructs a confident explanation claiming there is a “large yellow shiny cylinder.”

The Two Experiments

The researchers divided the study into two groups to isolate the effect of explanations:

- Experiment A (Answer Only): Participants saw the image, the question, and the AI’s answer.

- Experiment X (Answer + Explanation): Participants saw the image, the question, the AI’s answer, and the AI’s explanation.

The participants were then asked to rate the AI on several competencies:

- Color recognition

- Shape recognition

- Material recognition

- Scene understanding

- Overall competence

Figure 2 visualizes the hypothesis. In Experiment A, if the AI gets a color question wrong, the user should lower their trust in the AI’s color capability. In Experiment X, the researchers hypothesized that the explanation would make the error transparent. If the AI explains a color choice based on faulty logic (or hallucinates a color that isn’t there), the user should realize, “This AI is guessing,” and rate its color competence even lower, while perhaps maintaining trust in other areas like shape recognition.

The Hypotheses: What Should Happen?

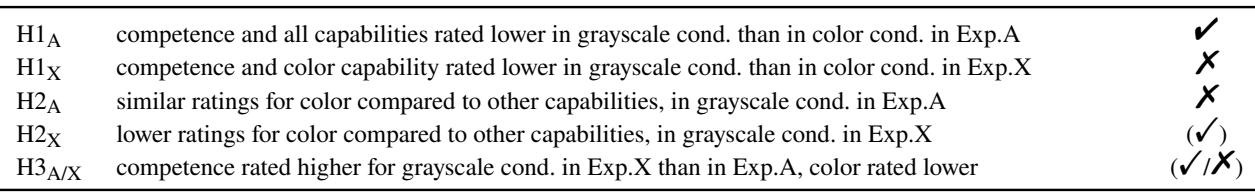

The researchers formulated specific hypotheses (H1-H3) regarding how users would react. The most critical were:

- H1 (Differentiation): In both experiments, users should rate the AI lower when it is in “grayscale mode” compared to “color mode” because the answers will be worse.

- H2 (Diagnosis): In the grayscale condition, users provided with explanations (Exp.X) should specifically rate the Color capability lower than other capabilities (like Shape or Material). This would indicate they successfully diagnosed the specific “colorblindness” of the system.

- H3 (Transparency vs. Illusion): Competence ratings might be higher overall with explanations, but the color rating specifically should be lower or the same as the no-explanation group.

The Results: The Halo Effect of Explanations

The results of the study were striking and contradicted the optimistic view of Explainable AI. Instead of acting as a diagnostic tool, the explanations acted as a “competence amplifier,” regardless of whether the AI was actually right or wrong.

1. Did users notice the drop in performance?

Yes. When the AI was fed grayscale images, its performance naturally dropped (since the researchers selected items where grayscale inputs led to incorrect answers). Users in both groups noticed the answers were wrong and rated the systems lower than the full-color systems.

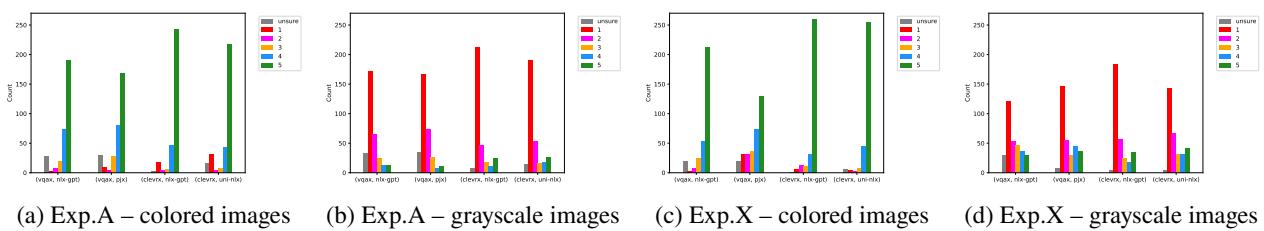

Figure 3 shows the distribution of ratings for Color Recognition.

- Charts (a) and (c) show the “Color” condition (AI sees color). The green bars are high—users trust the AI.

- Charts (b) and (d) show the “Grayscale” condition. The ratings shift left (lower trust).

However, look at the difference between (b) and (d). The drop in trust is less severe in Exp.X (d). Even when the AI was wrong because it couldn’t see color, the presence of an explanation made users judge it less harshly.

2. Did explanations help users diagnose the “Colorblindness”?

No. This is the most crucial finding.

The researchers expected that in the grayscale condition, users would say: “Okay, this AI understands shapes and materials, but it is terrible at colors.”

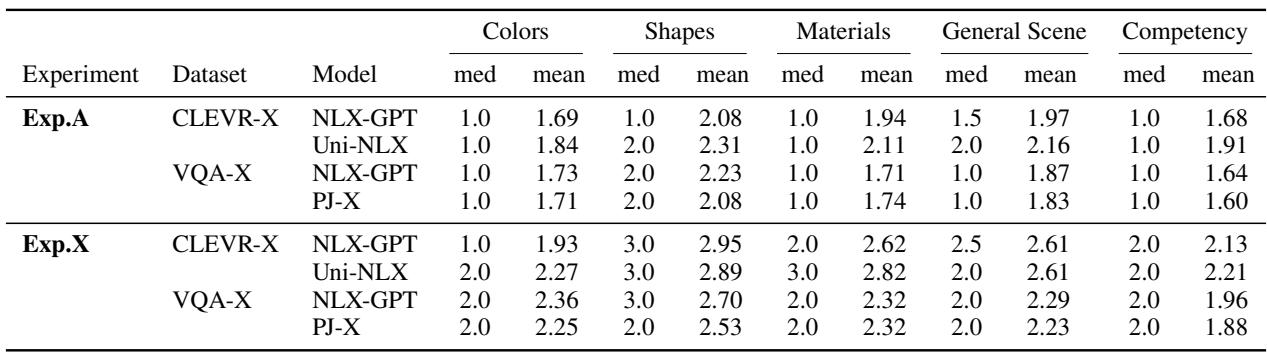

Table 1 reveals the reality. In Exp.A (No Explanation), the mean rating for “Colors” (1.69 for NLX-GPT on CLEVR-X) is low. But look at Exp.X (With Explanation). The mean rating jumps to 1.93.

More importantly, look at the spread across capabilities. Users did not punish the “Color” capability significantly more than “Material” or “Shape.” They simply rated the AI as “generally competent” or “generally incompetent.” The explanations did not help them isolate the specific fault.

3. The Illusion of Competence

The researchers found a broad “illusion of competence.” When an explanation was present, users rated the AI significantly higher on all capabilities—Color, Shape, Material, and Scene Understanding—even though the AI was actually failing the task.

Table 2 provides a stark summary. Hypothesis H2 and H3 were largely rejected.

- H2X (Diagnostic ability): Failed. Users did not rate color capability significantly lower than other capabilities relative to the no-explanation group.

- H3 (Transparency): Failed. Explanations increased the perceived competence of color recognition, rather than revealing the flaw.

The explanation text essentially successfully “bluffed” the users. By using fluent, grammatical sentences and mentioning relevant concepts (even incorrectly), the AI convinced users that it “knew” what it was doing.

Analyzing the “Why”: Plausibility over Truth

Why did this happen? The paper suggests that state-of-the-art VQA models are optimized for language modeling, which means they are very good at sounding plausible.

In the grayscale condition, the AI might answer a question about a “red sphere” by guessing. If it generates an explanation like, “Because it is a round object that is red,” the explanation is consistent with the answer, but it is not faithful to the visual input (which was gray).

Users, seeing a coherent sentence, attribute a higher level of reasoning to the system. They might think, “Well, it got the answer wrong, but it clearly knows what a red sphere is, so it must be smart.” They fail to realize the system is hallucinating the attribute “red” entirely.

Automated Metrics vs. Human Perception

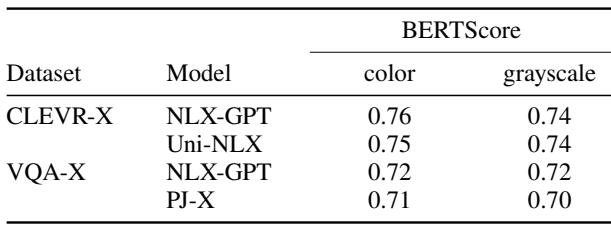

To further highlight the disconnect, the researchers compared their human findings with standard automated metrics used to evaluate these models, such as BERTScore.

Table 3 shows that BERTScore (which measures text similarity between the AI’s explanation and a ground-truth human explanation) found almost no difference between the Color and Grayscale conditions (e.g., 0.76 vs 0.74).

According to the automated metric, the AI was performing just fine in grayscale mode. This demonstrates a dangerous flaw in how we build AI: we optimize for metrics that reward fluent, human-like text, not necessarily factual grounding. The AI learned to produce high-scoring text, even when it was functionally blind.

Broader Implications

This study, while focused on a simple visual task, has profound implications for the deployment of Large Language Models (LLMs) and complex decision-support systems.

- The Danger of Eloquence: We are entering an era where AI systems are incredibly eloquent. They can write code, legal briefs, and medical advice. This paper suggests that eloquence is a confounding variable for trust. If a legal AI cites a non-existent case but explains its reasoning in perfect legalese, lawyers might be tricked into trusting it.

- Faithfulness is Hard: Creating explanations that truly reflect the “broken” parts of a model is difficult. If the model relies on a correlation (e.g., “grass implies green”), the explanation will sound correct (“I see green”) even if the perception is absent.

- User Training: Users are currently ill-equipped to audit AI explanations. We tend to trust fluent language. The study participants were not experts, but they represent the general public who will be using these tools.

Conclusion

The paper “The Illusion of Competence” provides a sobering reality check for the field of Explainable AI. The researchers demonstrated that providing natural language explanations does not automatically lead to better mental models. In fact, when an AI system has a specific defect—such as the inability to perceive color—explanations can mask this limitation by projecting a false sense of reasoning capability.

For students and future practitioners, the takeaway is clear: Do not confuse the output of an explanation module with the actual reasoning of the model. As we build the next generation of AI, we must move beyond plausibility and strive for explanations that are brutally honest about the system’s limitations—even if that makes the AI look a little less smart.

Key Takeaways:

- Explanations can mislead: They can increase trust even when the system is failing.

- Fluency \(\neq\) Competence: A grammatically correct explanation does not imply correct visual perception.

- Diagnostics are difficult: Users struggle to isolate specific failures (like color blindness) when distracted by confident explanations.

- Metrics need an update: Automated scores like BERTScore may validate “hallucinated” explanations, failing to capture the breakdown in grounding.

References within the blog post refer to the experimental items and results provided in the image deck.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2406.19170/images/cover.png)