The rise of Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 and Gemini has revolutionized how we interact with information. We ask complex questions, and these models generate fluent, human-like responses. However, there is a ghost in the machine: Hallucination. LLMs are notorious for confidently stating falsehoods as facts.

For English speakers, we have developed sophisticated tools to catch these lies. One of the gold standards is FActScore (Fine-grained Atomic Evaluation of Factual Precision), a metric designed to break down long generated texts into individual facts and verify them.

But the world doesn’t just speak English. As multilingual LLMs proliferate, a critical question arises: Does our ability to check for truth hold up when we switch languages?

In the research paper “An Analysis of Multilingual FActScore,” researchers from KAIST, Kensho Technologies, and Adobe Research take a deep dive into this problem. They dismantle the FActScore pipeline to see how it performs in Spanish, Arabic, and Bengali. Their findings reveal a stark reality: the tools we rely on to police AI truthfulness are significantly weaker in non-English settings, largely due to a lack of high-quality resources.

This post will walk you through their analysis, explaining how FActScore works, why it breaks down in low-resource languages, and what we can do to fix it.

1. The Core Problem: Factuality in a Multilingual World

Before diving into the methodology, we need to understand the stakes. When an LLM generates a biography of a famous person in English, it has access to a massive amount of training data. When we want to verify that biography, we have access to high-quality automated tools and a comprehensive English Wikipedia.

However, languages are generally categorized by “resource levels”—the amount of digital data available for that language:

- High-Resource: English, Spanish, French, Chinese.

- Medium-Resource: Arabic, Hindi.

- Low-Resource: Bengali, Swahili, Urdu.

The researchers hypothesized that the reliability of fact-checking metrics correlates with these resource levels. If an LLM generates a biography in Bengali, and our automated fact-checker also relies on Bengali data, will it catch a hallucination? Or will it hallucinate itself?

To test this, the authors focused on three distinct languages to represent the spectrum:

- Spanish (es): High-resource.

- Arabic (ar): Medium-resource.

- Bengali (bn): Low-resource.

2. Background: How FActScore Works

To understand the paper’s critique, you first need to understand the tool they are critiquing. FActScore is not a simple binary “True/False” label for a whole document. It is a granular pipeline.

The Equation of Truth

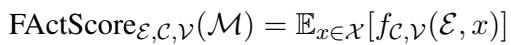

The core idea of FActScore is to measure precision: what percentage of the atomic claims made by the model are supported by a knowledge source?

Mathematically, it looks like this:

Here, \(A^{\mathcal{E}}(x)\) represents the set of “atomic facts” extracted from the text \(x\). The function returns an average of how many of those facts are true (indicated by the indicator function \(\mathbb{1}\)).

When evaluating a model (like GPT-4) overall, we take the expected value over a set of prompts:

The Four-Step Pipeline

This mathematical definition translates into a concrete software pipeline consisting of four components. The researchers scrutinized each one:

- Subject Model Generation: The LLM (e.g., GPT-4) generates a long-form text, such as a biography.

- Atomic Fact Extraction: A separate model breaks that text down into short, single-statement sentences (atoms).

- Example: “Barack Obama was born in Hawaii in 1961” \(\rightarrow\) “Barack Obama was born in Hawaii” AND “Barack Obama was born in 1961.”

- Retrieval: The system searches a Knowledge Source (usually Wikipedia) to find passages relevant to each atomic fact.

- Fact Scoring: An automated judge (usually another LLM) reads the retrieved passages and decides if the atomic fact is supported or not.

The authors’ goal was to find the “bottleneck”—which of these four steps causes the system to fail in multilingual settings?

3. Methodology: Native vs. Translated Data

One of the major contributions of this paper is the creation of a new dataset. Previous works often assessed multilingual performance by simply translating English datasets into other languages. The authors argue this is flawed because it introduces “cascading errors” from the translation process itself.

To get a true baseline, they created two datasets:

R1: The Translated Annotation

They took the original English FActScore dataset and used Google Translate to convert the atomic facts and knowledge sources into the target languages. This serves as a control group but is not the gold standard.

R2: The Native Annotation

This is the novel contribution. They hired native speakers of Spanish, Arabic, and Bengali. They selected biographies relevant to those specific cultures (local politicians, artists, etc.) rather than just translating biographies of Western figures.

- Subject Models Used: GPT-4 and Gemini-Pro-1.0 (GemP).

- Annotators: Native speakers who manually verified the generated facts to create a “Ground Truth.”

This “Native” dataset allows the researchers to see how FActScore behaves when operating entirely within the cultural and linguistic context of the target language.

4. Deep Dive: Analyzing the Components

The researchers systematically tested every gear in the FActScore machine. Let’s look at what they found for each component.

Component 1: Atomic Fact Extraction

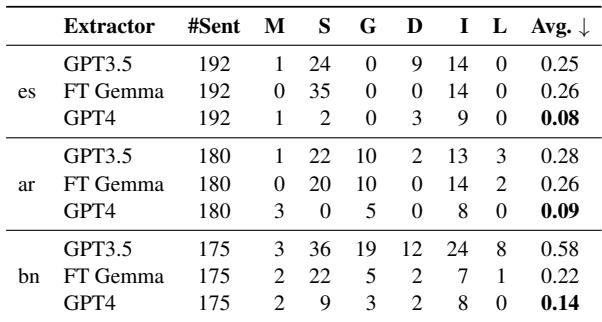

The first step is breaking a complex sentence into simple facts. If this fails, the whole evaluation fails. The researchers compared three models on this task: GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and a fine-tuned version of the open-source model Gemma.

They found that while GPT-4 is excellent, performance degrades as language resources drop. The types of errors change, too. In English, errors are usually just about splitting sentences poorly. In Arabic and Bengali, the models start making grounding errors—meaning the extracted fact claims something that wasn’t even in the original sentence.

Key Takeaway from Table 2: Notice the “Avg” (Average errors per sentence) column.

- GPT-4 is incredibly robust (0.08 - 0.14 error rate).

- GPT-3.5 struggles significantly in Bengali (0.58 error rate), making more than twice as many errors as it does in Spanish.

- Finetuned Gemma: Surprisingly, a smaller, open-source model that was specifically fine-tuned for this task (FT Gemma) actually outperformed GPT-3.5 in Bengali. This suggests that for specific tasks in low-resource languages, a specialized small model can beat a generalist giant.

Component 2: Fact Scoring

Once facts are extracted and evidence is retrieved, an “LLM-as-a-Judge” must decide: True or False?

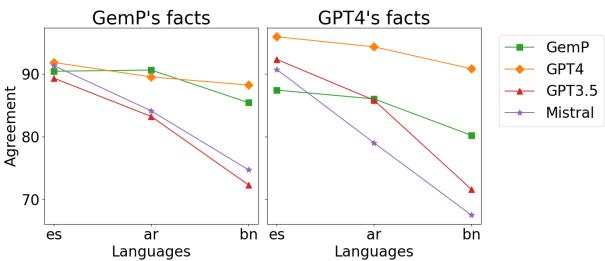

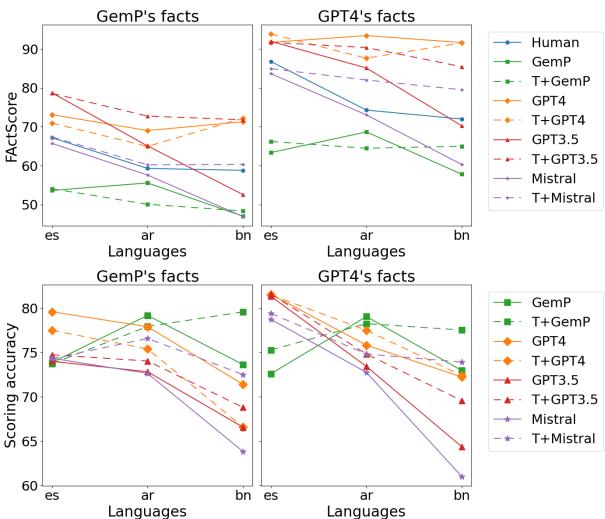

The researchers compared human ratings (Ground Truth) against judgments made by GPT-4, Gemini Pro (GemP), GPT-3.5, and Mistral.

Interpreting Figure 1:

- Upper Charts (FActScore): These show the estimated factuality score. Look at the Spanish (es) column vs. the Bengali (bn) column.

- GPT-4 (Orange line): Consistently overestimates factuality. It is too lenient.

- GemP (Green line): Consistently underestimates factuality. It is too strict.

- Lower Charts (Accuracy): This is the most damning metric. It measures how often the LLM agrees with the human.

- For Spanish (

es), accuracy is high (around 80%). - For Bengali (

bn), accuracy drops significantly for GPT-3.5 and Mistral. - Even the strongest models (GPT-4) show a decline in reliability as the resource level drops.

This proves that we cannot blindly trust an LLM to grade another LLM in low-resource languages.

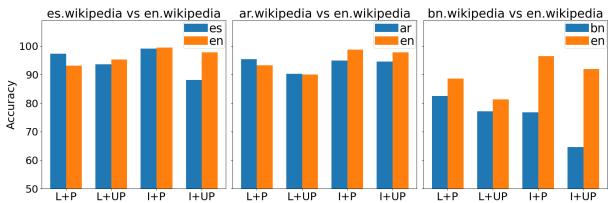

Component 3: The Knowledge Source

Perhaps the most insightful part of this paper is the critique of Wikipedia. The standard FActScore pipeline uses Wikipedia as the source of truth.

- Hypothesis: Wikipedia in Bengali is much smaller and less detailed than Wikipedia in English. Therefore, many true facts will be marked “False” simply because they aren’t in the Bengali Wikipedia.

To test this, they categorized entities into “Locally Popular” (e.g., a famous Bengali writer) vs. “Internationally Popular” (e.g., Barack Obama).

Insights from Figure 2:

- Blue Bars (Native Wiki): Accuracy using the native language Wikipedia.

- Orange Bars (English Wiki): Accuracy using the English Wikipedia.

Look at the Bengali (bn) section on the far right. The Orange bars are almost always higher than the Blue bars, even for local figures. This indicates that the Bengali Wikipedia is so sparse that it is often better to check English Wikipedia, even for Bengali-specific topics. This is a major limitation for automated evaluation in developing nations.

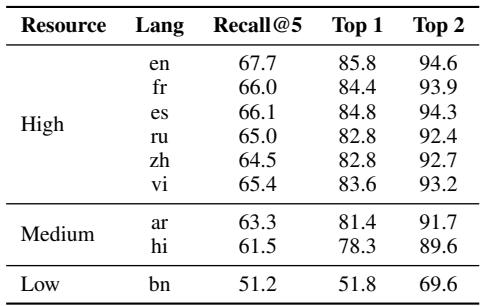

Component 4: The Retriever

The retriever is the search engine that finds relevant paragraphs. If the retriever fails to find the evidence, the scorer will incorrectly mark a fact as false.

Table 3 Analysis: The table measures Recall@5 (finding the right paragraph in the top 5 results).

- High Resource (es, fr, ru): Recall is around 66%.

- Low Resource (bn): Recall drops to 51%.

This 15% drop means that for Bengali, the system is flying blind half the time. It cannot find the evidence even if it exists.

5. Is Translation the Answer?

A common workaround in Natural Language Processing (NLP) is “Translate-Test.” Why not just translate the Bengali text into English and run the evaluation there?

The researchers tested this using their R1 and R3 (translated) datasets.

Figure 3 shows the agreement between evaluations done on native text vs. translated text.

- For GemP and GPT-4, the lines are relatively flat, meaning they are consistent regardless of translation.

- For GPT-3.5 and Mistral, performance falls off a cliff for Bengali (

bn).

Figure 4 offers a nuance. The dashed lines (Translation) sometimes perform better than the solid lines (Native), particularly for weaker models like GPT-3.5 in Arabic and Bengali (lower-left chart).

Why? Because the English tools (retrievers, scorers) are so much better that they outweigh the errors introduced by translation. However, relying on translation is risky because it introduces cultural nuances that literal translation might miss or distort.

6. Error Analysis: When Models Hallucinate the Grade

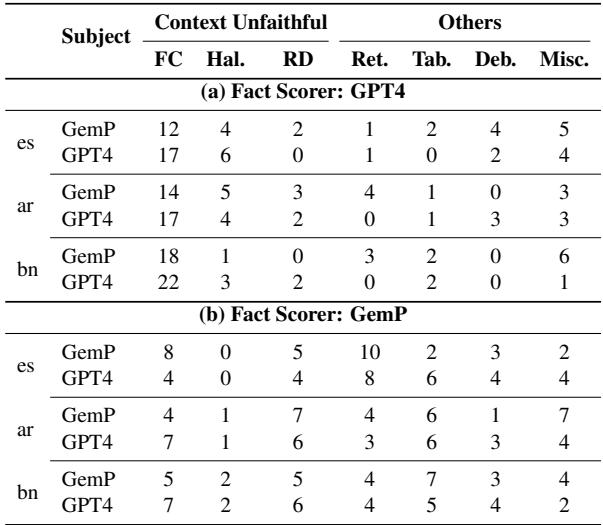

Why does GPT-4 overestimate factuality (as seen in Figure 1)? The researchers performed a qualitative error analysis to find out.

They discovered that GPT-4 suffers from Contextual Unfaithfulness.

- The Rule: The Scorer should only judge based on the retrieved Wikipedia passage.

- The Reality: GPT-4 ignores the passage and uses its own internal training memory.

If GPT-4 “knows” a fact is true, it marks it as “Supported,” even if the retrieved passage says nothing about it. While this might seem helpful, it ruins the purpose of the metric, which is to verify grounding in a source.

Table 4 highlights that Context Unfaithfulness is the dominant error for GPT-4 (first row), while Retrieval Error is a major issue for GemP.

7. Mitigations: How Do We Fix It?

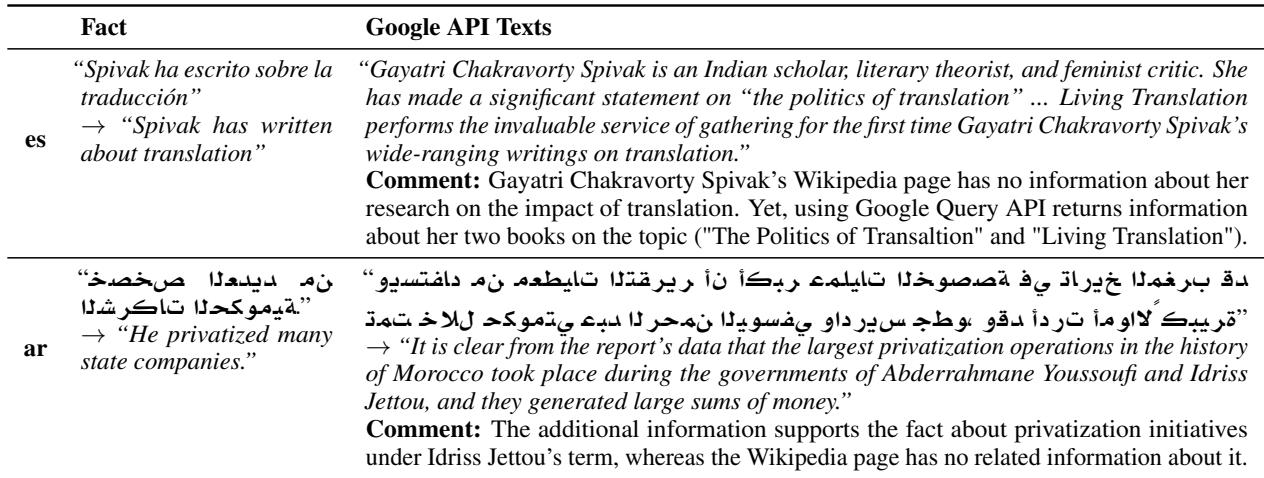

The paper doesn’t just present problems; it offers solutions. The authors recognize that the bottleneck is the Knowledge Source (sparse Wikipedia) and the Retriever.

They proposed three mitigation strategies to improve FActScore in low-resource languages:

- Expand Context (k=20): Retrieve 20 passages instead of just 8.

- Google Search (Internet): Instead of Wikipedia, use the entire internet via Google API.

- LLM Generation (GPT-4’s IK): Use GPT-4 to generate a background article about the entity, and use that as the evidence. (Basically, using GPT-4’s internal knowledge as a document).

The Results of Mitigation

The results were transformative.

Table 22 provides concrete examples. In the Spanish example, Wikipedia didn’t mention Spivak’s writings on translation. However, the Google Query API found books she wrote on the topic, allowing the model to correctly mark the fact as True.

The quantitative results (discussed in the paper’s Table 5 & 6) showed:

- Expanding Context helped slightly.

- LLM Generation helped significantly in high/medium resource languages.

- Google Search was the ultimate winner. It improved accuracy in Bengali from ~60% to 86.8%.

This proves that the “intelligence” of the models isn’t the only problem; the availability of information is the bottleneck. When we give the models access to the open internet rather than a limited Wikipedia, they become competent fact-checkers even in low-resource languages.

8. Conclusion & Implications

The paper “An Analysis of Multilingual FActScore” serves as a reality check for the AI community. As we rush to deploy multilingual models, our evaluation metrics remain Anglo-centric.

Key Takeaways:

- Inequality in Evaluation: Current tools penalize low-resource languages. A factual Bengali text might receive a low FActScore simply because the Bengali Wikipedia is small or the retriever is weak.

- The Wikipedia Ceiling: Wikipedia is not a sufficient knowledge base for global fact-checking. We must integrate the broader web or verified local databases.

- Internal Knowledge Bias: Strong models like GPT-4 often ignore the provided evidence, making them unreliable judges for strict “grounding” tasks unless carefully prompted.

- The Fix is Available: By moving from static Wikipedia dumps to dynamic internet search (Google API), we can drastically improve the fairness and accuracy of multilingual evaluation.

For students and researchers entering the field, this paper highlights that building the model is only half the battle. Validating it requires a deep understanding of the data ecosystem in which the model lives. As AI becomes global, our benchmarks must become global too—not just in translation, but in their fundamental design.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2406.19415/images/cover.png)