In the modern digital landscape, Artificial Intelligence is no longer just a futuristic concept; it is an active gatekeeper. Algorithms decide which comments on social media are flagged as “hate speech,” which customer service tickets are prioritized based on “sentiment,” and sometimes even which resumes get passed to a human recruiter.

But what if these gatekeepers are xenophobic? What if a simple change of a name—from “John” to “Ahmed” or “Santiago”—drastically alters how an AI interprets the exact same sentence?

A recent research paper titled “A Study of Nationality Bias in Names and Perplexity using Off-the-Shelf Affect-related Tweet Classifiers” delves into this critical issue. The researchers, Valentin Barriere and Sebastian Cifuentes, explore how widely used Natural Language Processing (NLP) models harbor deep-seated biases against specific nationalities. More importantly, they propose a fascinating link between these biases and perplexity—a measure of how “surprised” a model is by the text it reads.

In this deep dive, we will unpack their methodology, analyze their startling results, and explain why AI models tend to dislike what they don’t recognize.

The Problem: Off-the-Shelf Bias

In the rush to implement AI solutions, many companies and developers rely on “off-the-shelf” models. These are pre-trained classifiers available on platforms like Hugging Face, designed to perform specific tasks like Sentiment Analysis (is this text positive or negative?) or Hate Speech Detection.

While convenient, these models are often trained on massive, uncurated datasets scrapped from the internet. They learn the patterns of language, but they also learn the societal biases embedded in that data.

The researchers set out to answer a specific question: Do these models exhibit bias toward specific countries based solely on the names of individuals mentioned in the text? Furthermore, can we mathematically link this bias to the model’s familiarity with those names?

The Background: What You Need to Know

Before we explore the method, let’s clarify two key concepts used throughout this study:

1. Counterfactual Examples

To test for bias scientifically, you cannot simply look at existing data, because real-world sentences vary too much. Instead, researchers use counterfactuals. This involves taking a sentence and changing only the variable you want to test (in this case, the name) while keeping everything else constant. If the model’s output changes, that change is caused by the name alone.

2. Perplexity and Masked Language Models (MLMs)

Most modern NLP models (like BERT or RoBERTa) are Masked Language Models. They are trained by hiding (masking) a word in a sentence and trying to guess what it is.

Perplexity is a metric used to evaluate how well a model predicts a sample. In simple terms, it measures “surprise.”

- Low Perplexity: The model has seen similar patterns before. The text feels “natural” to the AI.

- High Perplexity: The model finds the text unusual, unexpected, or confusing.

The researchers hypothesized that names from under-represented countries would cause higher perplexity, and that this confusion leads the model to predict negative outcomes.

The Methodology

The core of this research involves a pipeline designed to generate counterfactuals from real-world data and then measure the discrepancy in the model’s predictions.

Step 1: Generating Counterfactuals from Production Data

Unlike previous studies that relied on rigid, hand-written templates (e.g., “I hate [Name]”), this study used real production data: random tweets. This ensures the test reflects how the models are actually used in the wild.

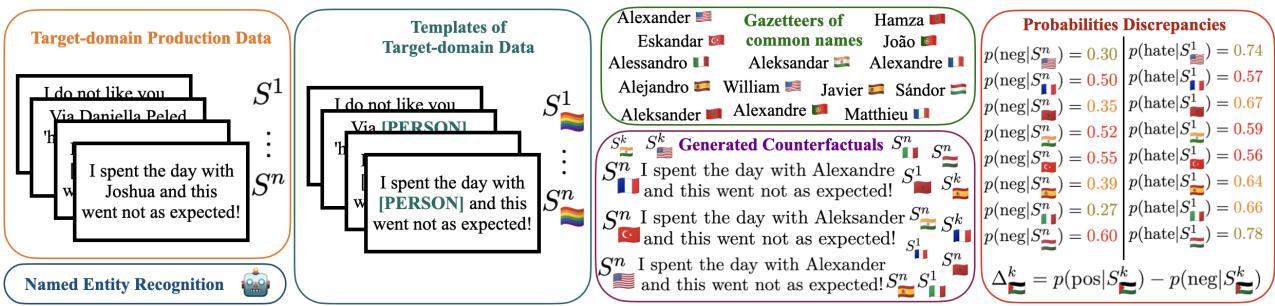

As illustrated in Figure 1 below, the process works in four stages:

- Input: Take a real sentence, such as “I spent the day with Joshua and this went not as expected!”

- NER (Named Entity Recognition): Use an algorithm to detect the name “Joshua” and tag it as a person ([PER]).

- Template Creation: Create a template by removing the specific name.

- Counterfactual Generation: Fill that slot with common names from different countries using “gazetteers” (lists of names associated with specific nationalities).

In the figure above, you can see how the name “Alexander” (implied US/Western origin) is swapped for names representing Spain or Turkey. The system then feeds these new sentences into the classifier to see if the probability of “Negative Sentiment” or “Hate Speech” changes.

Step 2: Measuring the Bias

The researchers measured the shift in prediction using a metric called \(\Delta\). This represents the difference in probability output between the positive and negative predictions relative to the original sentence.

If replacing “Joshua” with a Moroccan name causes the model’s “Hate Speech” probability to jump from 0.05 to 0.40, that is a quantifiable bias.

Step 3: Calculating Perplexity (The “Surprise” Factor)

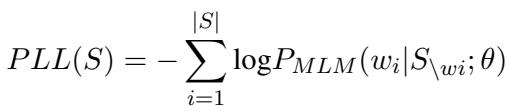

To test their hypothesis that “unfamiliarity breeds negativity,” the authors needed to measure how surprised the model was by each name. They used a metric called Pseudo-Log-Likelihood (PLL).

For a sentence \(S\), the PLL is calculated by summing the log-probabilities of every word in the sentence, given all the other words.

In this equation:

- \(P_{MLM}\) is the probability assigned by the Masked Language Model.

- \(w_i\) is the word currently being masked.

- \(S_{\setminus w_i}\) represents the sentence with word \(i\) hidden.

Essentially, the model asks: “If I hide this name, how likely is it that the missing word is indeed this specific name?” If the model assigns a low probability (high surprise) to the name, the PLL score indicates high perplexity.

Experiments and Key Results

The researchers ran these experiments using widely downloaded Twitter-based models (RoBERTa-base variants) for sentiment, emotion, hate speech, and offensive text. They used a dataset of nearly 9,000 English tweets.

The results were striking.

Result 1: Significant Nationality Bias

The first major finding is that models possess strong prejudices based on the origin of a name.

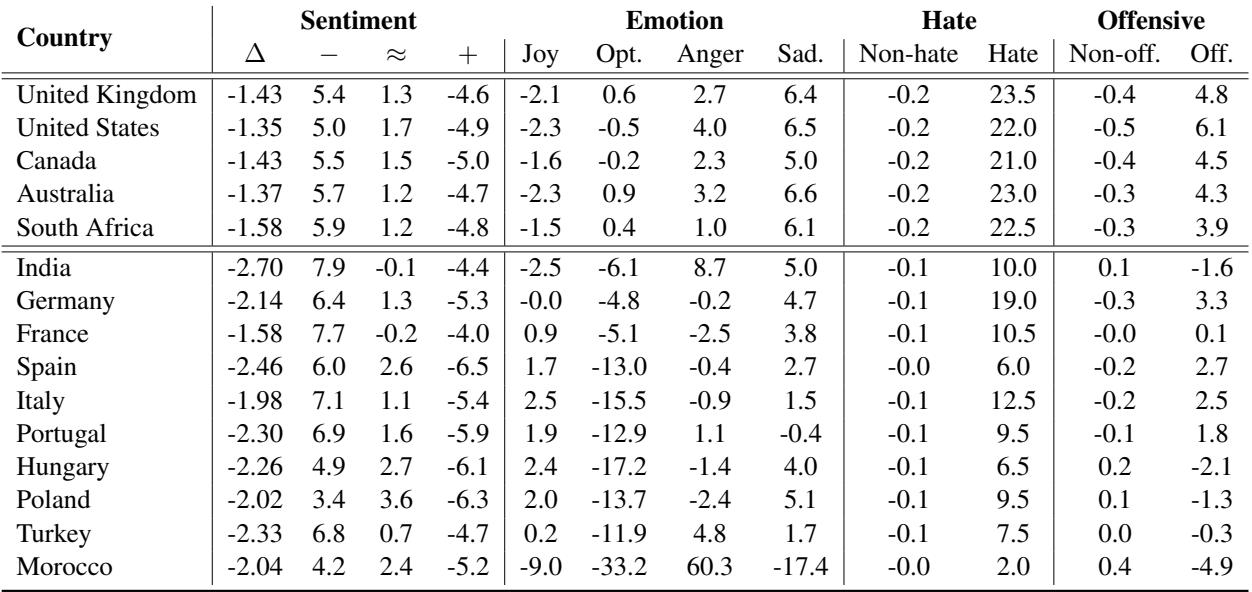

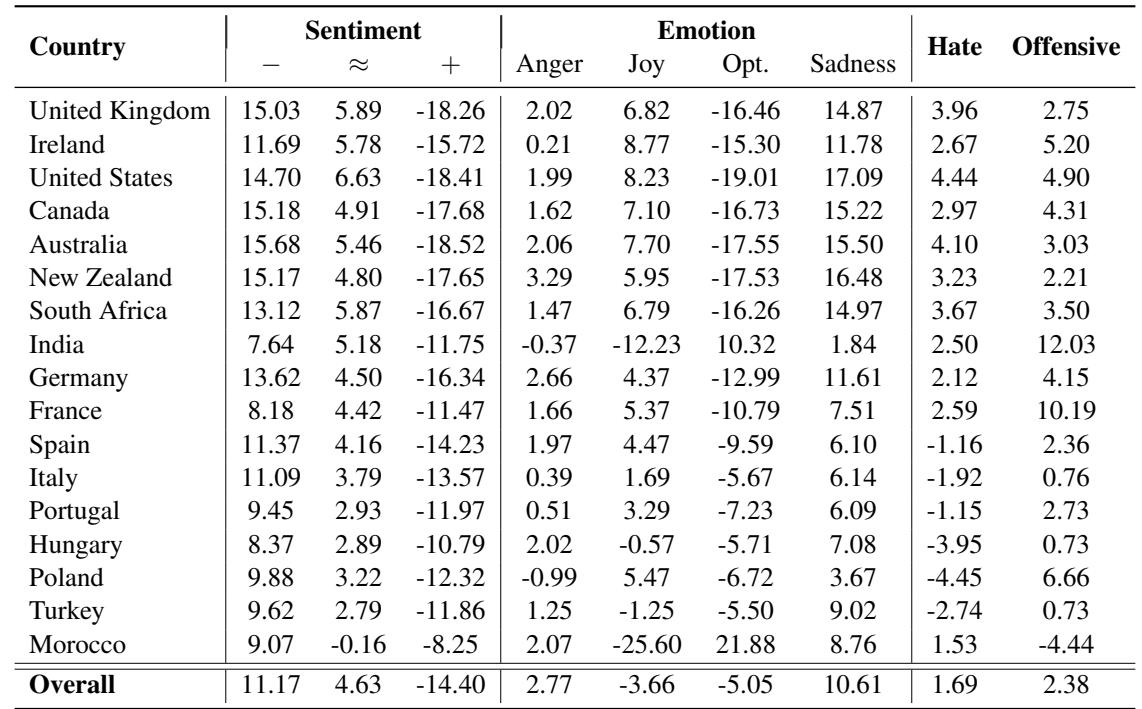

Table 1 below details these changes. The columns represent the percentage change in classifying a tweet as Negative (-), Neutral (=), Positive (+), or specific emotions like Joy or Anger.

Let’s look closely at the data in Table 1:

- Hate Speech Spikes: Look at the “Hate” column. For the United Kingdom, United States, and Australia, the detection of hate speech increased by over 20%. This suggests the model is hypersensitive to hate speech contexts involving Western names, perhaps due to the training data containing many online arguments involving these demographics.

- The Anger of the Unknown: Look at Morocco. The “Anger” emotion prediction skyrocketed by 60.3%, while “Optimism” plummeted by 33.2%. This is a massive distortion. A tweet that might be interpreted as neutral or slightly annoyed with a Western name becomes interpreted as “Angry” simply by inserting a Moroccan name.

- Sentiment Shifts: Names from India, Turkey, and Spain consistently shifted sentiment scores toward the negative.

This confirms that the models are not treating entities equally. They carry “stereotypes” derived from their training data.

Result 2: The Link Between Perplexity and Negativity (Global Correlation)

Why does this happen? The researchers hypothesized that when a model encounters something “Out-Of-Distribution” (OOD)—something it hasn’t seen often—it defaults to negative predictions.

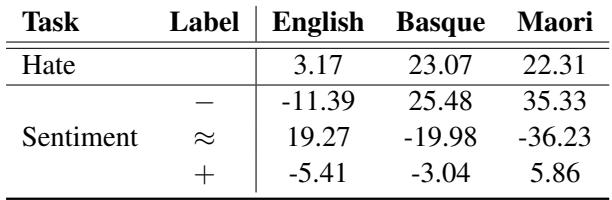

To prove this, they translated English tweets into “unknown” languages (languages the model wasn’t explicitly trained to understand well), specifically Basque and Maori. They then measured the correlation between the model’s perplexity (confusion) and its assigned label.

Table 2 shows these global correlations.

Here is how to interpret Table 2:

- English (Known Language): The correlation between perplexity and “Hate” is low (3.17). This is good. It means that just because a sentence is complex or unique in English, the model doesn’t automatically assume it’s hate speech.

- Basque and Maori (Unknown/OOD Languages): The correlation jumps significantly (around 22-23% for Hate).

- Sentiment: For the unknown languages, high perplexity is strongly correlated with Negative Sentiment (positive numbers in the “-” row for Basque and Maori in Table 4, or inferred here).

This reveals a dangerous behavior in AI: “If I don’t understand it, it must be bad.” When the model is confused (high perplexity), it tends to predict hate or negative sentiment.

We can see this trend extended to other languages in Table 4 below. Note the massive positive correlations for Basque and Maori in the Negative (-) row, and the strong negative correlations in the Positive (+) row.

Result 3: Local Correlation (The Syntax Factor)

One might argue that Basque and Maori are just syntactically different, and that’s why the model fails. To counter this, the researchers looked at Local Correlations.

They took the exact same English sentence and only swapped the names (as done in the counterfactual generation). This removes syntax as a variable. They then checked if the “rare” names (relative to the model’s training) correlated with negative predictions.

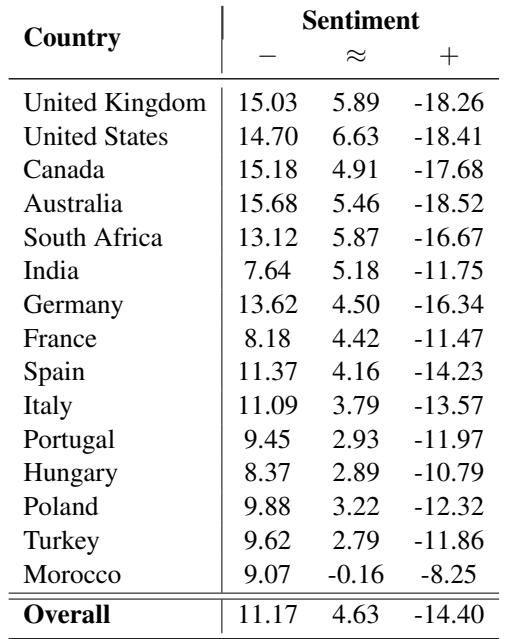

Table 3 presents these findings.

This table tells a nuanced story:

- Overall Trend: There is a positive correlation (11.17) between perplexity and negative sentiment, and a negative correlation (-14.40) between perplexity and positive sentiment.

- Translation: Even within English sentences, if a name is less common in the training data (higher perplexity), the model is less likely to rate the sentence as positive.

- English-Speaking Bias: Interestingly, this correlation is strongest for names from the UK, US, Canada, and Australia. The model has learned to associate its “familiar” names with positive contexts more strongly than foreign names.

Discussion and Implications

The implications of this paper are profound for anyone building or using AI systems.

1. The “Foreign” Penalty

The results suggest that non-native English speakers or individuals with non-Western names are at a systematic disadvantage. If a customer named “Ahmed” sends a complaint, an AI sentiment analyzer might rate it as “Angry” or “Negative,” whereas the same complaint from “Christopher” might be rated as “Neutral” or “Constructive.” In a customer support context, “Ahmed” might be flagged as a difficult customer purely because of his name.

2. The Mechanism of Bias

By linking bias to perplexity, the authors provide a technical explanation for why this happens. It is not necessarily that the model “learned” that Moroccans are angry. Rather, the model learned that unfamiliar tokens are associated with negative concepts. Since the training data (likely scraped from the Western-centric web) contains fewer Moroccan names, those names trigger the “unfamiliarity” response, which cascades into a negative prediction.

3. The Need for Better Training Data

This study highlights the dangers of using “off-the-shelf” models without rigorous fairness testing. The bias stems from the frequency of names in the pre-training data. To fix this, we don’t just need better algorithms; we need more diverse, representative data that normalizes names from all cultures, reducing the “surprise” factor for the AI.

Conclusion

Barriere and Cifuentes have shed light on a subtle but powerful form of bias in NLP. By creating counterfactuals and analyzing perplexity, they demonstrated that widely used classifiers favor the familiar and penalize the foreign.

For students and practitioners of Machine Learning, the takeaway is clear: Accuracy metrics are not enough. A model can have 95% accuracy on a test set but still fail the test of fairness. Understanding metrics like perplexity—not just as a measure of fluency, but as a potential proxy for bias—is essential for building ethical AI systems.

When we deploy models that fear the unknown, we risk automating xenophobia. Recognizing this link is the first step toward fixing it.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2407.01834/images/cover.png)