Introduction

In the rapidly evolving world of Artificial Intelligence, we have reached a point where generating text is easy. We have models that can write poetry, code in Python, and summarize legal documents in seconds. However, we have hit a new, arguably more difficult bottleneck: Evaluation. How do we know if the text the model generated is actually good?

Traditionally, the gold standard for evaluation has been human judgment. You show a human two summaries and ask, “Which one is more accurate?” But as Large Language Models (LLMs) scale, human evaluation becomes prohibitively expensive, slow, and sometimes subjective. This has led to the rise of the “LLM-as-a-Judge” paradigm, where powerful models like GPT-4 are used to grade the work of smaller models.

But this approach has flaws. Relying on proprietary, closed-source models for evaluation creates a “black box” problem. Furthermore, using synthetic data (data generated by AI) to train evaluators can create feedback loops where models reinforce their own biases.

Enter FLAMe, a new family of Foundational Large Autorater Models introduced by researchers at Google DeepMind and Google. In their paper, Foundational Autoraters: Taming Large Language Models for Better Automatic Evaluation, the authors propose a robust solution: training evaluator models on a massive, highly curated collection of human judgments—not AI-generated ones.

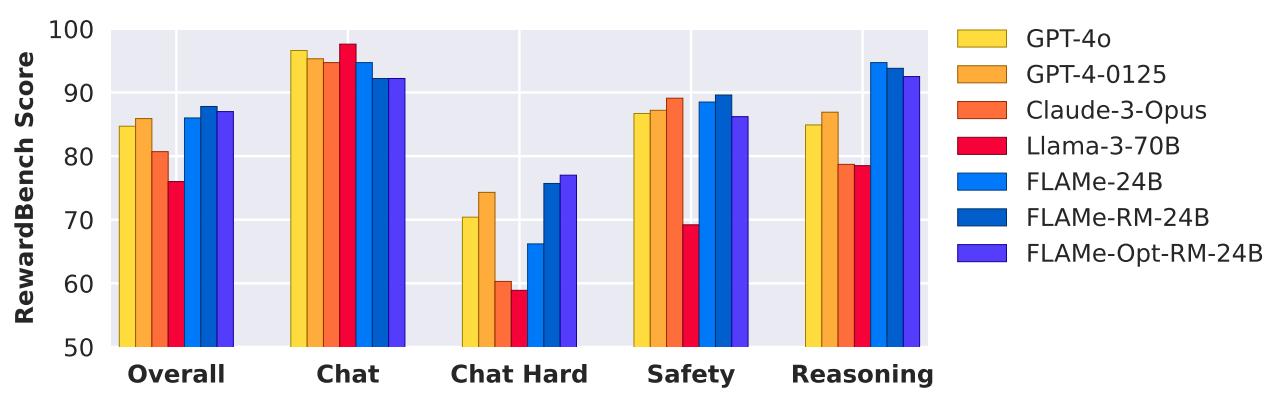

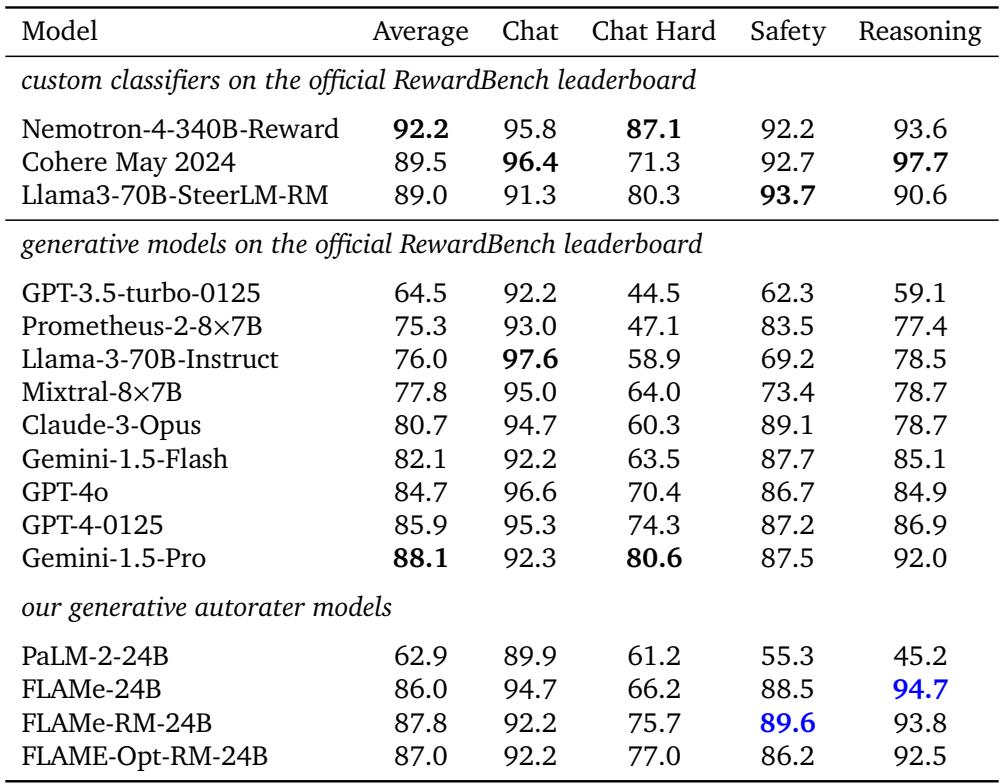

As shown in the figure below, their results are striking. Their specialized model, FLAMe-RM, outperforms industry heavyweights like GPT-4-0125 and GPT-4o on the RewardBench leaderboard, despite being trained solely on permissively licensed, open data.

In this post, we will tear down the methodology behind FLAMe, explore how the authors curated 5.3 million human judgments, and examine the novel “tail-patch” fine-tuning strategy that makes these models so efficient.

The Background: Why Do We Need Autoraters?

Before diving into the architecture of FLAMe, it is essential for students to understand the landscape of LLM evaluation.

The Limits of Heuristics

In the past, Natural Language Processing (NLP) relied on overlap metrics like BLEU or ROUGE. These metrics simply counted how many words in the machine-generated text overlapped with a human-written reference. While useful for simple tasks, these metrics fail miserably for complex, open-ended tasks. A sentence can be perfectly factual and fluent without sharing a single word with a reference sentence.

The Rise of LLM-as-a-Judge

To solve this, researchers started prompting LLMs to act as judges. You might feed a prompt to GPT-4: “Please rate the following summary on a scale of 1 to 5 for helpfulness.”

While effective, this method introduces bias. LLMs often prefer longer answers (verbosity bias), prefer answers that appear first (positional bias), or simply prefer their own output (egocentric bias). Moreover, relying on GPT-4 for evaluation is expensive and violates the Terms of Service of many proprietary models if used to train competitors.

The FLAMe Hypothesis

The researchers behind FLAMe hypothesized that the best way to build a fair, general-purpose judge is to go back to the source: Human data. By aggregating a massive diversity of human evaluation tasks, they believed they could train a model to understand the underlying principles of quality, regardless of the specific task at hand.

The Core Method: Building FLAMe

The creation of FLAMe is a masterclass in data engineering and transfer learning. The process can be broken down into three pillars: Data Collection, Unified Formatting, and Model Training.

1. The Data: 5.3 Million Human Judgments

The foundation of this work is a new data collection. The authors didn’t just scrape the web; they meticulously curated 102 distinct quality assessment tasks from publicly available, permissively licensed research.

Crucially, they adhered to strict principles:

- No Synthetic Data: Every label in the dataset comes from a human annotator.

- Permissive Licensing: Only open-source data was used to ensure the resulting model could be released without legal gray areas.

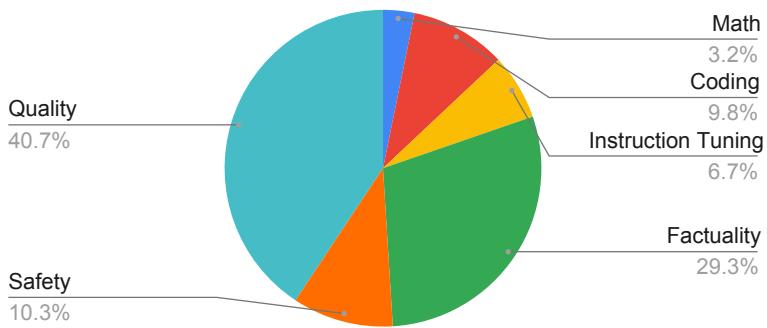

- Diversity: The data isn’t just about “helpfulness.” It covers distinct LLM capabilities.

As you can see in the breakdown below, the dataset covers the pillars of modern AI evaluation:

This diversity is vital. A model trained only to check for grammar (Quality) would be useless at detecting dangerous content (Safety) or incorrect code (Coding). By mixing 5.3 million judgments across these categories, the model learns a generalized representation of “what humans prefer.”

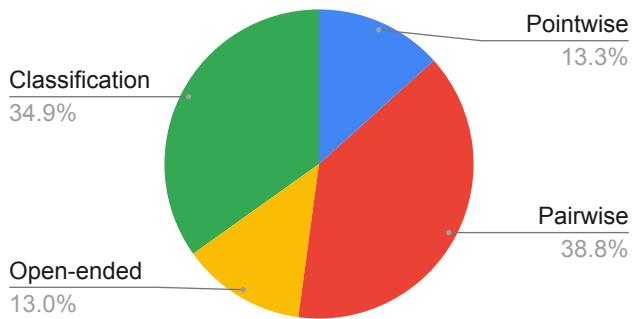

The authors also ensured a variety of Task Types. It is not enough to just ask “Is this good?” The data includes pairwise comparisons (A vs. B), pointwise ratings (Scale of 1-5), and classification (Yes/No).

2. The Unified Text-to-Text Format

One of the biggest challenges in multitask learning is that every dataset looks different. One dataset might have columns for “Prompt” and “Response,” while another has “Article” and “Summary.”

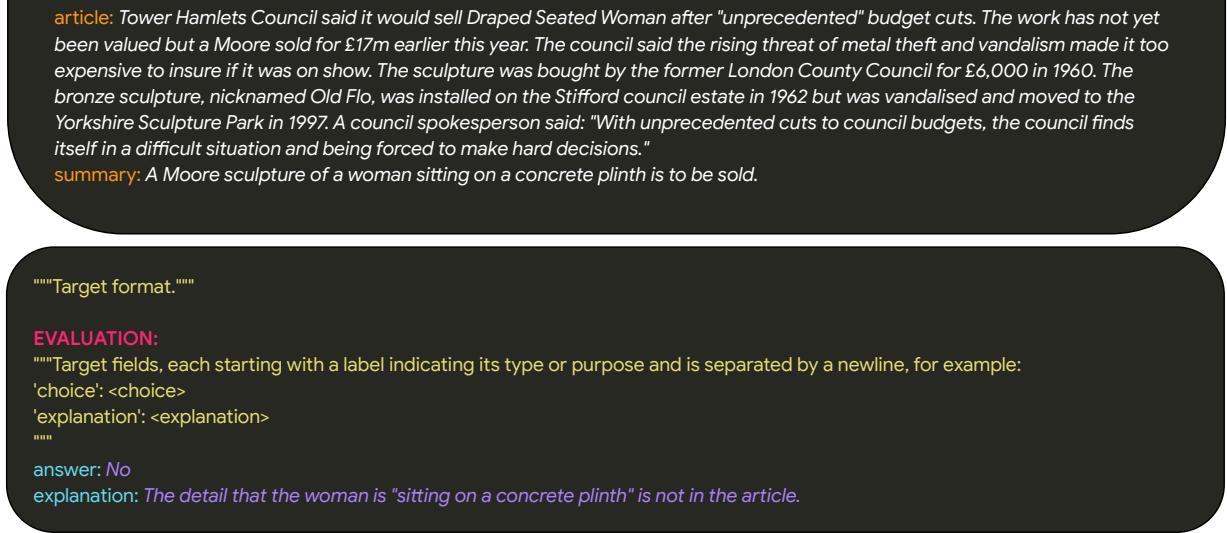

To solve this, the authors converted all 102 tasks into a single text-to-text format. They treated evaluation as a translation problem: translating a context into a judgment.

They manually crafted instructions for every single task. This means the model isn’t just seeing data; it is seeing the definition of the task every time.

Take a look at the architecture of a training example below:

In this figure, you can see the structure:

- Instructions: A clear definition of what “attributable” means.

- Context: The source article and the summary to be evaluated.

- Evaluation (Target): The human label (No) and the explanation.

By standardizing the input, the model can seamlessly switch between grading a Python script and checking a news summary for hallucinations.

3. The Three Model Variants

The authors trained a PaLM-2-24B model (an instruction-tuned base) in three different ways to test their hypothesis.

Variant A: FLAMe (The Generalist)

This model was trained on the entire collection of 102 tasks using supervised multitask training for 30,000 steps. The data was mixed proportionally, meaning larger datasets appeared more often (capped to prevent one dataset from dominating).

Result: This produced a strong general-purpose evaluator that generalized well to new, unseen tasks.

Variant B: FLAMe-RM (The Specialist)

The authors wanted to see if they could beat proprietary models on Reward Modeling (specifically the RewardBench benchmark). They took the base FLAMe model and fine-tuned it further for just 50 steps on a balanced mixture of four specific datasets related to chat, reasoning, and safety.

Result: This slight “nudge” in training resulted in state-of-the-art performance for open-weight models.

Variant C: FLAMe-Opt-RM (The Efficient Engineer)

This is perhaps the most technically interesting contribution. The authors recognized that training on everything isn’t always efficient if you have a specific target in mind (like RewardBench).

They introduced a Tail-Patch Fine-Tuning Strategy. Here is how it works:

- Take a model that is partially trained.

- Fine-tune it exclusively on one specific task for a short time (a “tail-patch”).

- Measure if that specific task helped or hurt performance on the target benchmark.

- Assign weights to tasks based on this analysis (Helpful tasks get high weights; harmful tasks get low or zero weights).

This allows the researchers to mathematically determine the “perfect recipe” of data mixture for a specific goal.

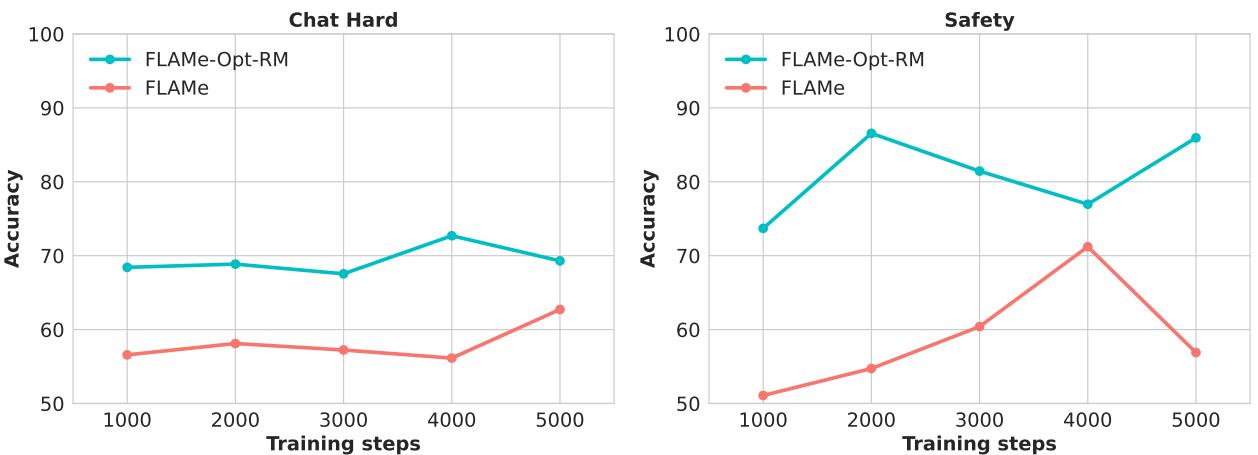

As shown in Figure 5, the optimized model (FLAMe-Opt-RM) learns much faster. It reaches high accuracy on “Chat Hard” and “Safety” tasks in a fraction of the steps compared to the standard FLAMe model (the red line), which actually degrades on safety tasks over time due to suboptimal data mixing.

Experiments & Results

The authors evaluated FLAMe against a suite of 12 benchmarks, but the most significant comparisons were against proprietary “LLM-as-a-Judge” models like GPT-4, Claude-3, and Llama-3-70B.

RewardBench Dominance

RewardBench is a comprehensive benchmark that evaluates how well a model can distinguish between good and bad responses across Chat, Reasoning, and Safety categories.

The results for FLAMe-RM are impressive. It achieved an overall accuracy of 87.8%.

Looking at the table above, compare the FLAMe-RM-24B row to the GPT-4-0125 row.

- Overall: FLAMe-RM (87.8) > GPT-4-0125 (85.9).

- Chat Hard: FLAMe-RM (75.7) > GPT-4-0125 (74.3).

- Safety: FLAMe-RM (89.6) > GPT-4-0125 (87.2).

This is a massive achievement for open science. A 24-billion parameter model, trained on public data, outperformed the massive, proprietary GPT-4 on evaluating response quality.

Generalization to Held-Out Tasks

It is easy to overfit to one benchmark. To prove FLAMe is a true generalist, the authors tested it on 11 other benchmarks that were not in the training set (held-out tasks).

FLAMe outperformed the proprietary models on 8 out of 12 total benchmarks. Specifically, it excelled in:

- Factuality: On the LLM-AggreFact benchmark, FLAMe-24B scored 81.1%, beating GPT-4’s 80.6%.

- Code Re-ranking: When asked to pick the best Python code snippet from a list of generated options (HumanEval), FLAMe significantly improved the success rate of code generation models, proving it can “read” code quality better than many competitors.

The Bias Check: CoBBLEr

A major criticism of using LLMs as judges is bias. The authors tested FLAMe on the CoBBLEr benchmark, which measures:

- Egocentric Bias: Does the model prefer its own outputs?

- Length Bias: Does it just pick the longer answer?

- Order Bias: Does it always pick option “A”?

The analysis revealed that FLAMe is significantly less biased than GPT-4. Because it was trained on a diverse set of human judgments (which naturally vary), it learned to look at the content rather than superficial features like length or sentence order.

Conclusion & Implications

The FLAMe paper presents a compelling argument: we do not need to rely on black-box, proprietary models to evaluate our AI systems. By meticulously curating diverse, human-labeled data and converting it into a unified format, we can train “Foundational Autoraters” that are transparent, permissible, and highly effective.

Key Takeaways for Students:

- Data Quality over Quantity: FLAMe’s success wasn’t due to having more data than GPT-4, but having better, specific data (human evaluations) for the task of judging.

- Format Matters: The unified text-to-text format allowed the model to transfer knowledge across vastly different domains (e.g., learning about safety helped it understand reasoning).

- Efficiency through Optimization: The “Tail-Patch” method shows that you can scientifically engineer your training data mixture to achieve better results with less compute.

As LLMs continue to grow, the models that grade them must grow alongside them. FLAMe demonstrates that open research and public data can go toe-to-toe with closed industry giants, paving the way for more democratized and reliable AI evaluation.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2407.10817/images/cover.png)