Introduction

In the rapidly evolving world of Large Language Models (LLMs), engineers and researchers often face a dilemma when trying to improve performance: should they spend their time engineering better prompts, or should they collect data to fine-tune the model weights?

Conventionally, this is viewed as an “either/or” decision. Prompt engineering is lightweight and iterative, while fine-tuning is resource-intensive but generally more powerful. However, recent research suggests that we might be looking at this the wrong way. What if these two distinct optimization strategies aren’t competitors, but rather complementary steps in a unified pipeline?

A fascinating new paper from Stanford University, “Fine-Tuning and Prompt Optimization: Two Great Steps that Work Better Together,” proposes a novel approach: BetterTogether. The researchers demonstrate that by alternating between optimizing the prompt templates and fine-tuning the model weights, we can achieve results that significantly outperform either method in isolation.

This article explores how getting an LLM to “teach itself” through this alternating process can lead to massive performance gains—up to 60% in some complex reasoning tasks.

Background: The Rise of LM Programs

To understand why this approach is revolutionary, we first need to look at how modern NLP systems are built. We have moved past simple “chatbot” interactions where a user asks a question and the model answers immediately. Today, we build LM Programs.

An LM Program is a pipeline where a language model acts as a distinct module for various sub-tasks. The most common example is Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG). In a RAG pipeline, the system might first generate a search query, retrieve documents, filter those documents, and finally answer the user’s question based on the retrieved context.

The Optimization Challenge

Optimizing these pipelines is notoriously difficult. In a standard neural network, we have “labels” for every step and can use backpropagation (gradient descent) to update weights. In a modular LM pipeline:

- No Intermediate Labels: We usually only know if the final answer is correct. We don’t have ground truth data for the intermediate steps (e.g., was the search query perfect? We don’t know).

- Discrete Steps: The communication between modules is natural language (text), which breaks the gradient flow. You can’t easily backpropagate errors through a sentence.

Traditionally, developers use frameworks like DSPy to optimize the prompts (\(\Pi\)) for these modules. Others might try to fine-tune the weights (\(\Theta\)) of the underlying model. The authors of this paper argue that to truly maximize performance, we must optimize both \(\Theta\) and \(\Pi\) in tandem.

The Core Method: BetterTogether

The core hypothesis of the BetterTogether approach is simple yet profound: an LLM can teach itself to be better at a task, and a better model can utilize more complex prompts.

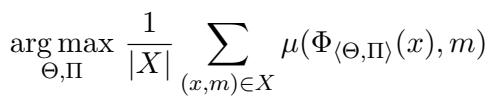

The researchers treat the optimization problem as maximizing a metric (like accuracy) over a dataset \(X\), by tweaking both the model weights \(\Theta\) and the prompts \(\Pi\).

As shown in the equation above, the goal is to find the configuration of Weights (\(\Theta\)) and Prompts (\(\Pi\)) that maximizes the average performance metric \(\mu\) across all examples.

The Algorithm: Alternating Optimization

The BetterTogether algorithm avoids the complexity of trying to optimize everything at once. Instead, it alternates between two specific operations: BootstrapFewShotRS (for prompts) and BootstrapFinetune (for weights).

Here is the step-by-step logic of how the system improves itself:

- Initial Prompt Optimization (\(\Pi\)): The system starts with a base model. It runs the training examples through the pipeline. It looks for “successful” runs—instances where the pipeline arrived at the correct final answer. It takes the intermediate steps from these successful runs and turns them into “few-shot” examples to include in the prompt.

- Weight Fine-Tuning (\(\Theta\)): Once the prompts are optimized, the system generates a new set of training data. It records the input/output of every module during successful runs. This creates a high-quality, synthetic dataset generated by the model itself. The model weights are then fine-tuned (using LoRA) on this data.

- Second Round Prompt Optimization (\(\Pi\)): Now that the model weights are tuned, the model behaves differently. It is smarter and more aligned with the task. The algorithm runs the prompt optimization step again. Because the underlying model is better, it can generate even higher-quality few-shot examples, further refining the prompts.

This cycle (\(\Pi \rightarrow \Theta \rightarrow \Pi\)) creates a positive feedback loop. The prompt optimization filters out bad reasoning, creating clean data for fine-tuning. The fine-tuning bakes that reasoning capability into the weights. The final prompt optimization polishes the interaction.

Deep Dive: The Modules

To visualize how this works in practice, let’s look at the specific programs used in the research. The authors implemented this strategy on three distinct tasks: HotPotQA (Multi-hop reasoning), GSM8K (Math), and Iris (Classification).

Multi-Hop Reasoning (HotPotQA)

HotPotQA is a complex task requiring the model to find information across multiple documents. It isn’t just one question; it’s a sequence of reasoning steps.

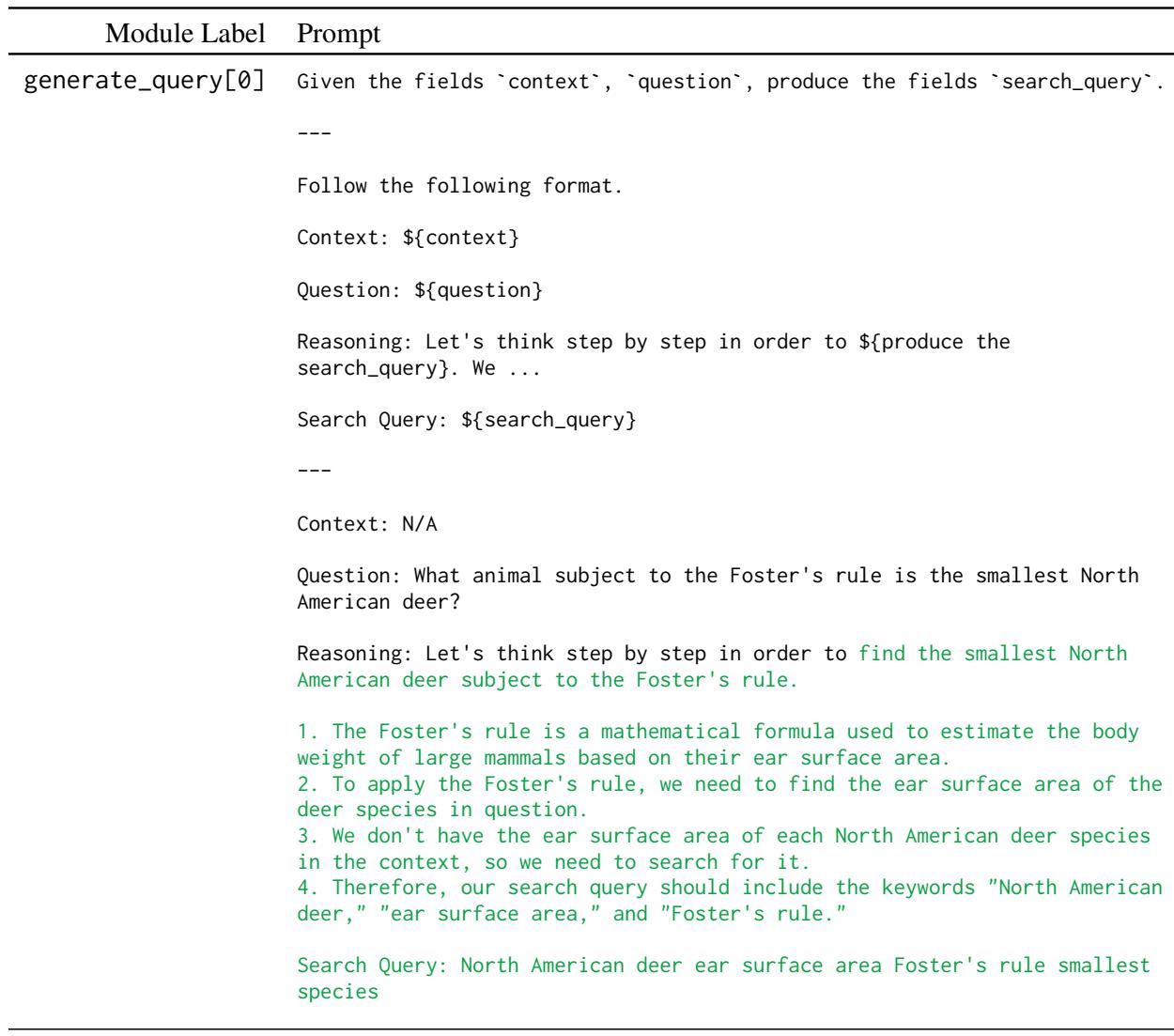

In Figure 1 (above), you can see the complexity of the “Prompt” (\(\Pi\)). It isn’t just a single instruction. It consists of multiple modules: generate_query (to search Wikipedia) and generate_answer.

- Step 1: The model generates a search query based on the question.

- Step 2: It reads the context and generates another query if needed (multi-hop).

- Step 3: It synthesizes the final answer.

Optimizing this manually is a nightmare. By using the BetterTogether approach, the system automatically finds the best examples to put into these prompt templates (the “Reasoning” sections in green), and then fine-tunes the model to be better at following those patterns.

Arithmetic Reasoning (GSM8K)

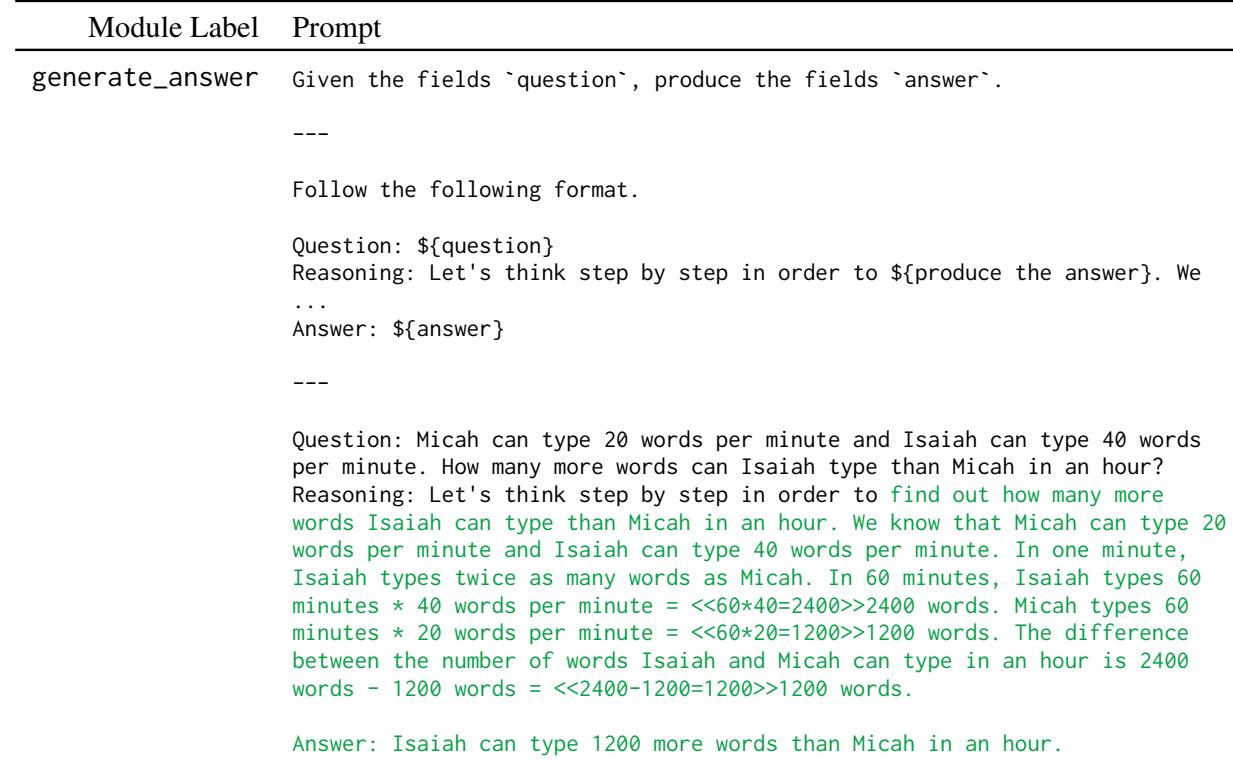

Mathematical reasoning requires a different type of precision. The model must follow a strict chain of thought to arrive at the correct number.

As shown in the figure above, the module generate_answer is optimized to produce a step-by-step reasoning trace. In the “BetterTogether” pipeline, the fine-tuning step ensures the model learns the arithmetic logic, while the prompt optimization ensures the model structures its output correctly for the parser.

Classification (Iris)

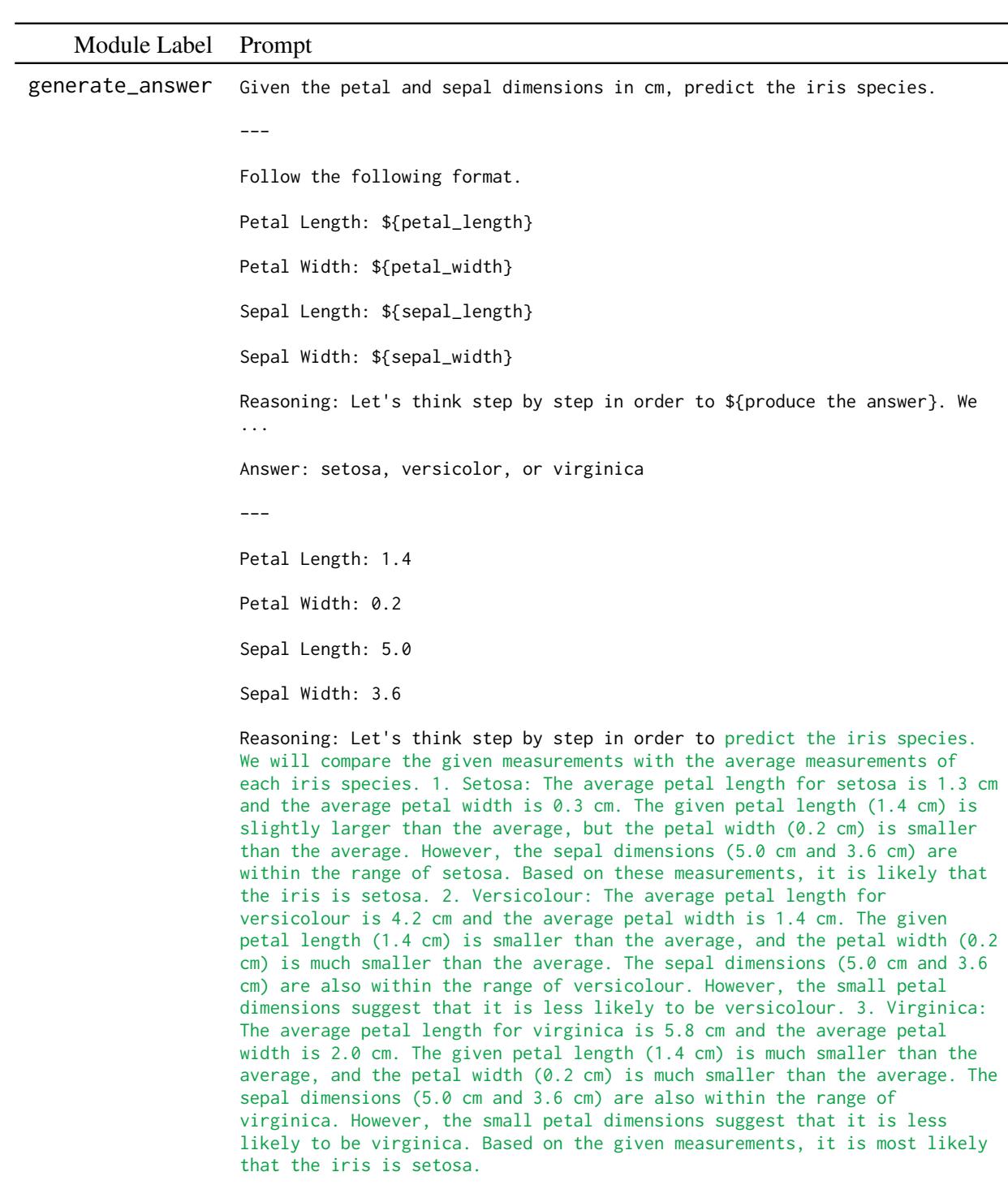

Interestingly, the researchers also tested this on the standard Iris classification dataset to see if the method holds up on non-language tasks (predicting flower species from measurements).

Even here, treating classification as a language program allows the model to “reason” about petal lengths and widths (as seen in the generated green text), improving accuracy over standard methods.

Experiments & Results

The researchers evaluated their method using three different Large Language Models: Mistral-7b, Llama-2-7b, and Llama-3-8b. They compared the “BetterTogether” strategy against three baselines:

- Zero-shot: The model out of the box.

- Prompt Opt Only (\(\Pi\)): Only optimizing prompts.

- Weight Opt Only (\(\Theta\)): Only fine-tuning.

The dominance of combined strategies

The results were compelling. Across almost all tasks and models, combining prompt optimization and fine-tuning beat the individual strategies.

Key Findings:

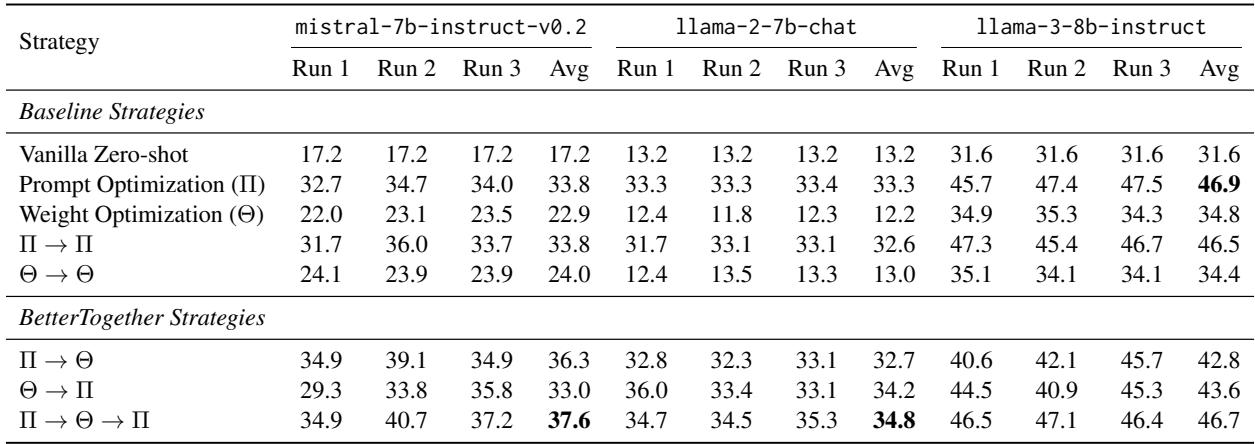

- HotPotQA: This task saw the most dramatic gains. For example, on Llama-2-7b, the “BetterTogether” strategy (\(\Pi \rightarrow \Theta \rightarrow \Pi\)) achieved nearly 35% accuracy, compared to just 12.2% for weight optimization alone.

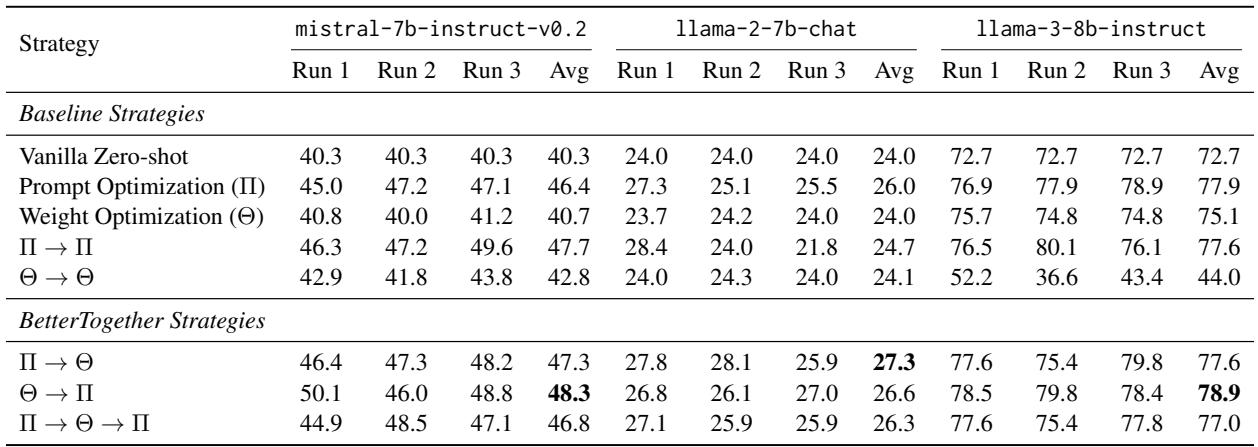

- GSM8K: While math is generally harder to improve via prompts alone, the combined approach squeezed out additional gains, pushing accuracy higher than fine-tuning alone.

We can see the detailed breakdown of these runs below.

The table above (HotPotQA results) highlights the consistency of the method. Notice the row \(\Pi \rightarrow \Theta \rightarrow \Pi\). It consistently performs at the top tier across different models. This validates the “sandwich” approach: optimize prompts to get good data, fine-tune the model, then optimize prompts again to fit the new model.

Similarly, for GSM8K (above), the combined strategies consistently hover at the top performance levels. It is worth noting that for math, simply fine-tuning (\(\Theta\)) is very effective, but adding prompt optimization layers (\(\Theta \rightarrow \Pi\)) pushes the boundary further, specifically for the Llama-3-8b model.

Why does this work?

The authors suggest that prompt optimization acts as a filter. When we train a model (fine-tuning), we want to train it on correct reasoning. If we just run a raw model, it might produce many wrong answers or correct answers with bad reasoning.

By optimizing the prompt first, we increase the likelihood of the model generating high-quality, correct reasoning traces. When we then fine-tune on these traces, we are effectively distilling the model’s “best self” into its weights.

Conclusion

The “BetterTogether” paper provides a practical roadmap for the future of NLP system engineering. It moves us away from the binary choice of “prompting vs. fine-tuning” and toward a unified optimization lifecycle.

For students and practitioners, the takeaways are clear:

- Don’t settle for one: If you have a modular pipeline, you leave performance on the table if you only optimize prompts or only fine-tune.

- Let the model teach itself: You don’t always need massive external datasets. You can bootstrap your own training data by prompting the model to succeed and then training on those successes.

- Order matters: The \(\Pi \rightarrow \Theta \rightarrow \Pi\) sequence is particularly powerful because it cleans the data before training and refines the interface after training.

As LLMs continue to be integrated into complex software pipelines, strategies like BetterTogether that automate the optimization of the entire system—weights and code alike—will likely become the industry standard.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2407.10930/images/cover.png)