Introduction

In the rapidly evolving landscape of Artificial Intelligence, Multimodal Large Models (MLLMs)—AI capable of processing and generating text, images, and video simultaneously—have taken center stage. From GPT-4 to Sora, these models are pushing the boundaries of creativity and functionality. However, beneath the surface of these impressive capabilities lies a persistent engineering bottleneck: the “chicken and egg” problem of data and model development.

Historically, the paths to improving AI have been bifurcated. You have model-centric development, where researchers obsess over architecture tweaks and training algorithms, often assuming the data is a fixed variable. Then, you have data-centric development, where engineers clean and curate massive datasets, often relying on intuition or heuristics without knowing exactly how that data will interact with a specific model until the expensive training run is finished.

This siloed approach is inefficient. It leads to wasted computational resources and suboptimal models. What if you spend weeks cleaning a dataset based on a rule that actually hurts your specific model’s performance? What if a model architecture requires a specific type of data diversity that your cleaning script filtered out?

In this post, we will dive deep into a new research paper that proposes a solution: the Data-Juicer Sandbox. This feedback-driven suite is designed to bridge the gap between data and models, enabling a systematic “co-development” workflow. We will explore how this sandbox allows researchers to probe, analyze, and refine their data recipes using real model feedback, ultimately achieving state-of-the-art results—including topping the VBench video generation leaderboard—while using a fraction of the computational resources.

The Problem: Isolated Development Trajectories

To understand why the Data-Juicer Sandbox is significant, we first need to understand the current friction in MLLM development.

Training a large model is incredibly expensive. Because of the high cost of “full training,” developers often treat data processing as a preprocessing step that happens before the model gets involved. They might apply filters to remove “low quality” images or text based on general statistics (like image resolution or text length).

However, “quality” is subjective and model-dependent. A dataset optimized for a CLIP model (image-text matching) might need different characteristics than a dataset optimized for a Diffusion Transformer (text-to-video generation). When these two development tracks—data and model—don’t talk to each other, you get:

- Inefficient Resource Utilization: Training on data that doesn’t actually help the model learn.

- Suboptimal Outcomes: Missing out on performance gains because the data recipe wasn’t tuned to the model’s specific needs.

The researchers behind Data-Juicer Sandbox argue that we need a “sandbox laboratory”—a safe, cost-controlled environment where we can run many small experiments to understand the interplay between data operators (OPs) and model performance before scaling up.

The Solution: The Sandbox Laboratory Architecture

The Data-Juicer Sandbox acts as a middleware layer. It sits between raw data processing (handled by the Data-Juicer system) and model training frameworks (like PyTorch or specific model implementations like LLaVA or EasyAnimate).

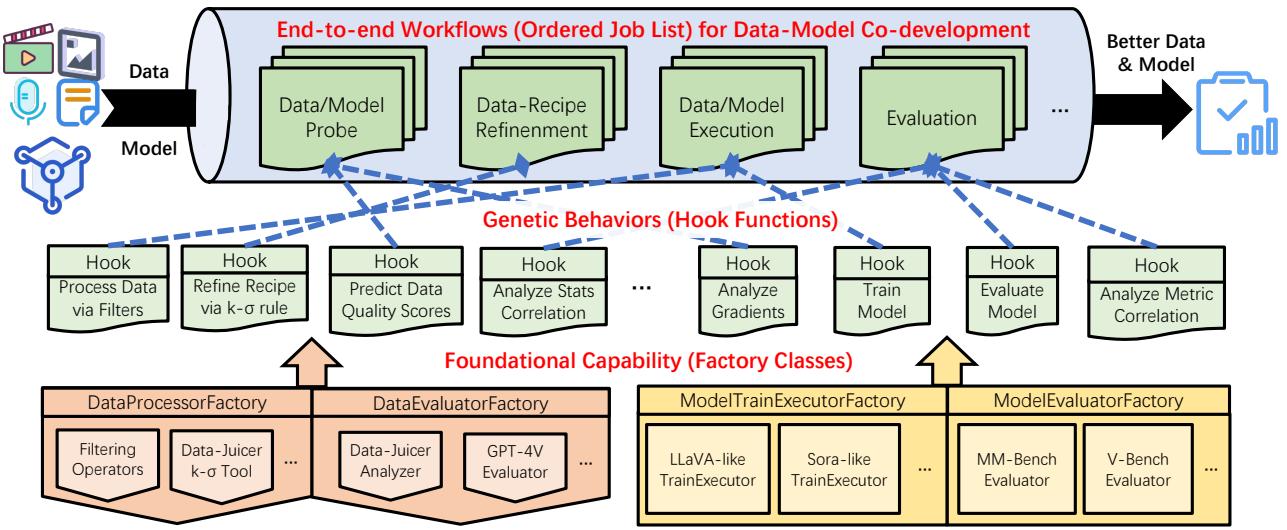

As shown in the architecture diagram above, the Sandbox is orchestrated in layers:

- Workflows (Top Level): Defined sequences of jobs, such as “Probe Data” \(\rightarrow\) “Refine Recipe” \(\rightarrow\) “Train Model” \(\rightarrow\) “Evaluate.”

- Behaviors (Middle Level): These are hook functions that define specific actions, like calculating correlations between data stats and model loss, or applying specific filters.

- Capabilities (Bottom Level): The factory classes that do the heavy lifting—filtering data, calculating metrics (like perplexity or aesthetic scores), and executing training loops.

This structure allows users to “plug and play” different models and data strategies without rewriting the entire codebase.

The Core Method: Probe-Analyze-Refine

The heart of the paper is the Probe-Analyze-Refine workflow. This is the scientific method applied to AI training. Instead of guessing which data is good, the sandbox systematically tests hypotheses.

Let’s break down this workflow step-by-step, as illustrated in the figure above.

Stage 1: Probing with Single-Operator Data Pools

The first question a developer usually asks is: “Which data processing operators (OPs) actually matter?”

There are dozens of ways to filter data: by text length, by image aspect ratio, by “aesthetic score,” by how well the text matches the image (CLIP score), etc. To find out which ones drive performance, the Sandbox creates Single-OP Data Pools.

- Take the full raw dataset \(\mathcal{D}\).

- Select a specific operator (e.g.,

Image NSFW Filter). - Process the data and split it into buckets based on the operator’s statistics: Low, Middle, and High.

- Train small “probe” models on these specific buckets (and a random control group).

- Evaluate the models.

If the model trained on the “High Aesthetic Score” pool performs significantly better than the random baseline, you know that aesthetic quality is a crucial factor for this specific model task. If it performs worse, you might be filtering out necessary diversity.

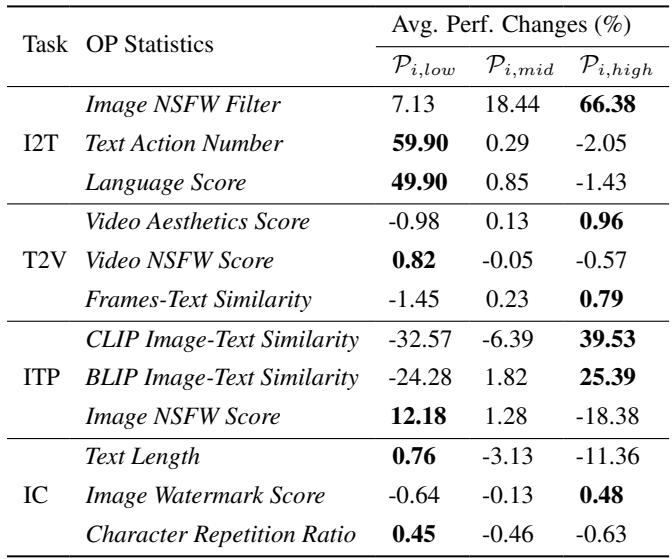

The researchers ran this probing phase across various tasks. The results, summarized in the table below, reveal that different tasks require vastly different data recipes.

Key Insight: Notice how for Image-to-Text (I2T) tasks, the Image NSFW Filter (High) gave a massive +66.38% improvement relative to baseline in some metrics. However, for other tasks, the impact varies. This confirms that “one size fits all” data cleaning does not exist.

Stage 2: Analyzing Multi-Operator Recipes

Once you know which individual operators work, the next temptation is to just combine all the “good” ones. However, the researchers found that combining top operators does not always yield better results.

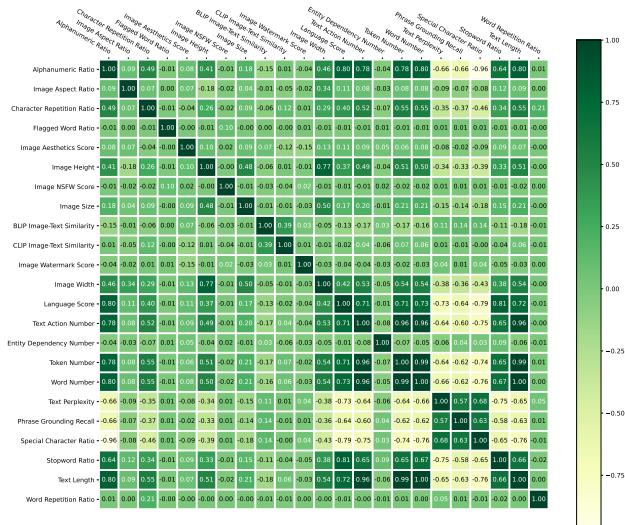

Sometimes, two filters might be redundant (filtering out the same data). Other times, they might be contradictory. To solve this, the Sandbox uses Correlation Analysis.

By calculating the Pearson correlation coefficients between different data statistics and model metrics, the system can identify which operators are orthogonal (independent) and which are correlated.

In the correlation matrix above, green indicates positive correlation and red indicates negative. The Sandbox uses this data to cluster operators. The strategy is to pick the best-performing operator from different clusters to ensure you are improving the data along multiple, non-overlapping dimensions (e.g., one operator for visual quality, one for text complexity, one for alignment).

The researchers tested this by creating “recipes.” Interestingly, they found that simply stacking the Top-3 performing operators sometimes hurt performance compared to using just the Top-1. This highlights the complexity of data interactions—filtering too aggressively with multiple criteria can reduce data diversity to the point where the model fails to generalize.

Stage 3: Refining and Scaling (The Data Pyramid)

After identifying the optimal combination of operators (the “Recipe”), the final step is scaling. But there’s a trade-off: as you apply more filters to get higher quality, you are left with less data.

The Sandbox tackles this with a Pyramid-Shaped Data Pool approach:

- Top of Pyramid: Very high quality, strict filtering, small volume.

- Bottom of Pyramid: Lower quality, loose filtering, massive volume.

The researchers posed a critical question: Is it better to train on a huge amount of mediocre data, or to repeat high-quality data multiple times?

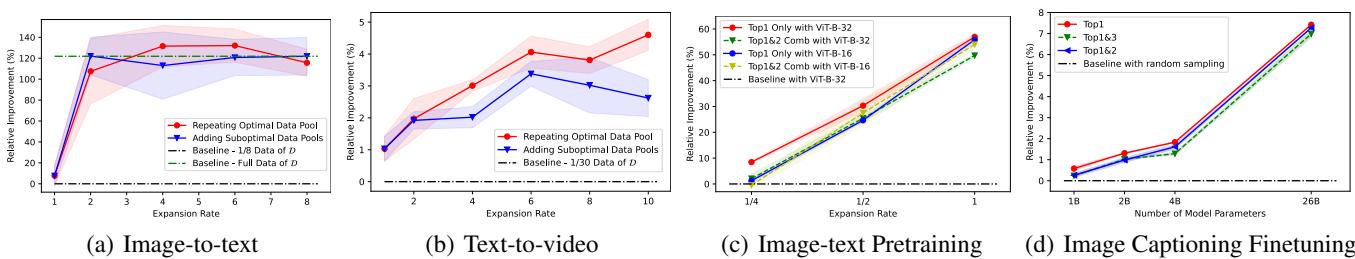

The results (shown in Figure 3 above) were striking.

- Image-to-Text (a): Repeating the high-quality data (red line) significantly outperformed adding suboptimal data (blue line) and the full baseline dataset (green line).

- Scaling Laws: For Image-Text Pretraining (c), they observed clear power-law scaling. As they increased compute (training for more epochs) on the high-quality subset, performance continued to rise linearly.

This implies that data quality is often more important than data quantity, provided you are willing to train on that high-quality data for longer (multiple epochs).

Case Studies and Key Results

To prove the Sandbox works in the real world, the authors applied it to three distinct, high-difficulty multimodal tasks.

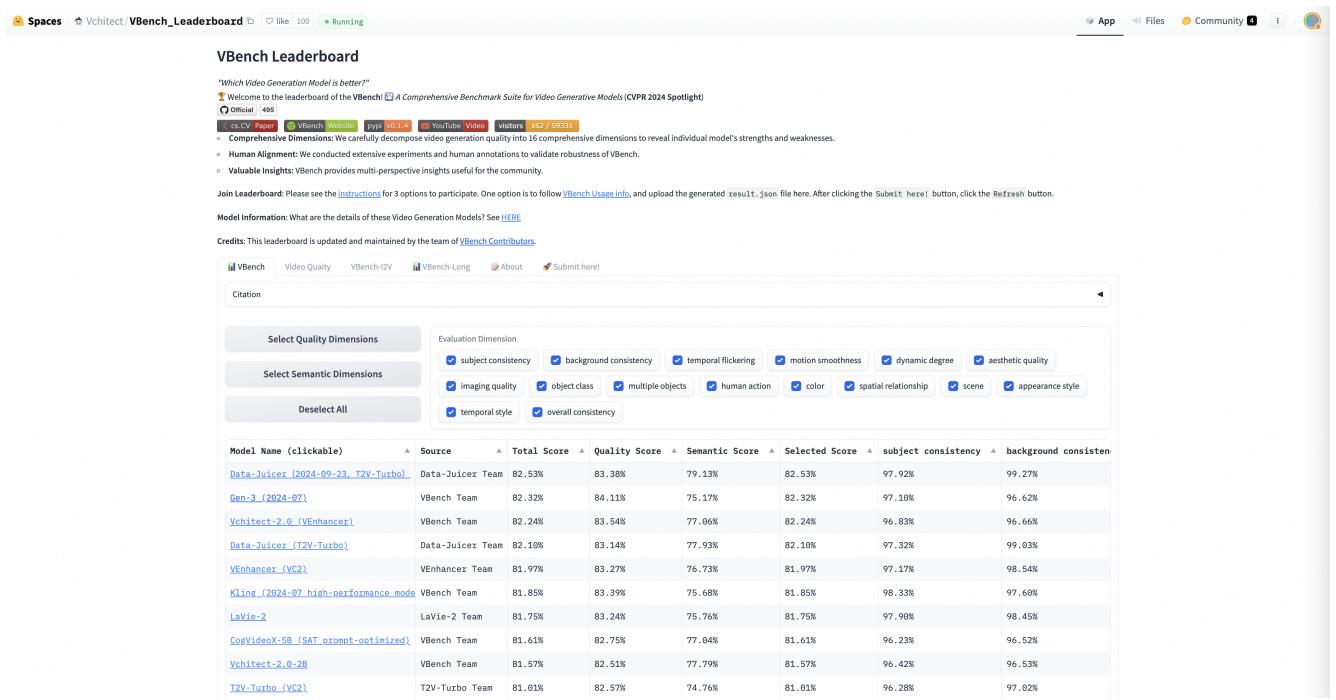

1. Text-to-Video Generation: Topping the Leaderboard

The most impressive result came from the Text-to-Video (T2V) experiments. Video generation is notoriously difficult and computationally expensive.

The team started with a base model (T2V-Turbo/VideoCrafter-2) and applied the Sandbox workflow.

- Probe: They found that video-specific operators (like

Video Motion ScoreandVideo Aesthetics) were far more critical than text operators. - Refine: They created a dataset of just 228k high-quality videos (a tiny fraction of typical training sets).

- Result: They trained a model called “Data-Juicer (DJ)” that achieved Rank 1 on the VBench Leaderboard, beating commercial and proprietary models like Gen-3 and Kling.

This victory wasn’t just about raw performance; it was a victory of efficiency. By using the Sandbox to identify exactly which videos to train on, they achieved state-of-the-art results with significantly less compute than their competitors.

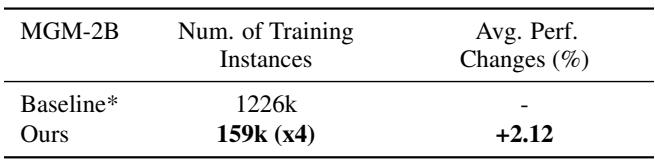

2. Image-to-Text: The MGM Model

For Image-to-Text generation (e.g., “describe this image”), they experimented with the Mini-Gemini (MGM) model.

Using the insights from the Sandbox, they constructed a training set that was only 1/10th the size of the original distinct instances. By training on this high-quality subset (and repeating it), they outperformed the baseline model trained on the full, massive dataset.

This result challenges the prevailing “Big Data” wisdom. It suggests that a significant portion of the data we currently feed into MLLMs might actually be noise that distracts the model.

3. Image-Text Pretraining: Scaling Laws

Finally, they looked at CLIP models (used for connecting text and images). They confirmed that the insights from small-scale “probe” experiments transfer to larger scales. A recipe that worked for a small ViT-B-32 model also worked when scaled up to larger architectures and longer training runs. This “transferability” is crucial because it validates the core premise of the Sandbox: you can learn cheap lessons on small models and apply them to expensive large models.

Beyond Filtering: Diversity and Generative Refinement

The Sandbox isn’t just about deleting bad data. It also provides tools to analyze diversity.

Using the analysis tools, the researchers generated word clouds to visualize the content of their data pools based on NSFW scores.

They found that “High NSFW” pools didn’t just contain explicit content; they contained specific semantic categories (like beauty, tattoos, and art) that were otherwise rare. This explains why Image-to-Text models (which need to recognize everything) benefited from “High NSFW” data—it added diversity. In contrast, Text-to-Video models (which need to generate aesthetically pleasing content) suffered when trained on this data.

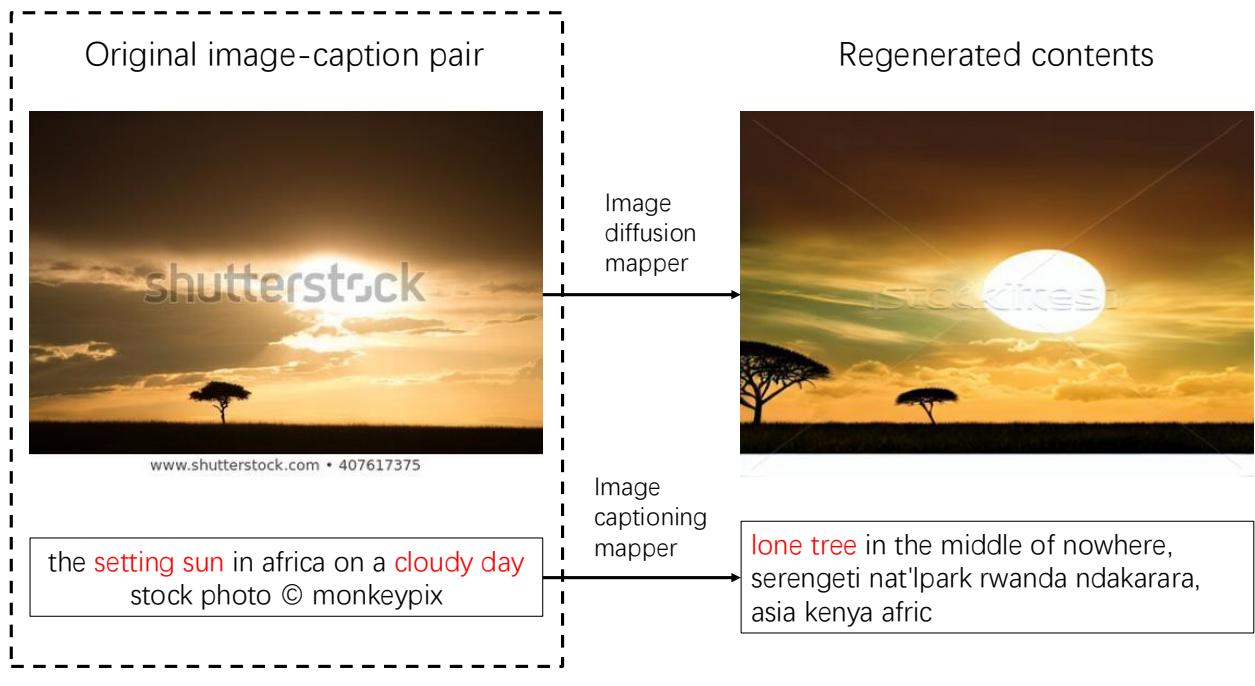

Furthermore, the Sandbox supports Generative Mappers. These are operators that don’t just filter data but change it. For example, using a diffusion model to regenerate a noisy image based on its caption, or using a captioning model to rewrite a bad description.

As shown above, the Sandbox can take a low-quality input and “upcycle” it into a high-quality training sample, effectively creating better data out of thin air.

Conclusion

The Data-Juicer Sandbox represents a shift from intuition-based AI development to evidence-based co-development. By providing a structured environment to probe, analyze, and refine data recipes, it turns the “black art” of data curation into a rigorous engineering discipline.

The key takeaways from this work are:

- Data-Model Coupling: There is no “perfect dataset” in a vacuum. The best data depends entirely on the model architecture and the target task.

- Efficiency Wins: You don’t always need more data. You need better data. Repeating high-quality data often beats adding more low-quality data.

- Transferable Insights: Lessons learned from small, cheap experiments in the Sandbox can reliably scale up to state-of-the-art model training.

As multimodal models continue to grow in size and complexity, tools like the Data-Juicer Sandbox will be essential. They allow researchers to navigate the infinite search space of data possibilities, ensuring that the massive compute resources of the future are spent learning from the signal, not the noise.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2407.11784/images/cover.png)