Lost in Translation? Why Machine Translation Might Be the Secret Weapon of Multilingual AI

If you have been following the explosion of Natural Language Processing (NLP) over the last few years, you are likely familiar with the heavy hitters: BERT, GPT, and T5. These models have revolutionized how machines understand human language. Recently, the focus has shifted toward multilingual models—systems capable of understanding and generating text in dozens, sometimes hundreds, of languages simultaneously.

However, there is a scientific “crisis of comparison” in this field. When a new multilingual model is released, it often differs from previous models in every conceivable way: it has a different architecture, it was trained on a different dataset, it has a different number of parameters, and it uses a different training objective. When Model B outperforms Model A, is it because the architecture is better? Or was it just trained on more data?

In the paper “A Comparison of Language Modeling and Translation as Multilingual Pretraining Objectives,” researchers from the University of Helsinki and Université Bretagne Sud set out to solve this “apples-to-oranges” comparison problem. They created a strictly controlled environment to answer a fundamental question: Does teaching a model to translate between languages create a better “understanding” of language than standard monolingual modeling?

In this post, we will break down their methodology, explore the specific architectures they compared, and analyze why “Machine Translation” might be an underappreciated powerhouse for pretraining foundation models.

The Problem: Apples, Oranges, and Pears

To understand why this paper is important, we first need to look at how modern Language Models (LMs) are usually pretrained. Generally, they fall into two camps regarding their objective (what the model tries to achieve during training):

- Monolingual Objectives: The model looks at text in Language A and tries to predict missing words or the next word in Language A. It might do this for many languages, but it rarely sees explicit links between languages during training.

- Cross-lingual Objectives: The model is explicitly shown how Language A relates to Language B (e.g., via translation pairs).

The hypothesis is that translation (an explicit cross-lingual signal) should force the model to learn deeper semantic representations. If a model knows that “chat” in French and “cat” in English refer to the same concept, it has learned something profound about the world, not just about French or English grammar.

However, proving this hypothesis is difficult because existing models like mBERT (Masked Language Model) and mT5 (Encoder-Decoder) are too different to compare fairly. This paper removes those variables.

The Controlled Environment

The researchers focused on two primary variables: Model Architecture and Pretraining Objectives. To ensure a fair fight, they controlled for everything else:

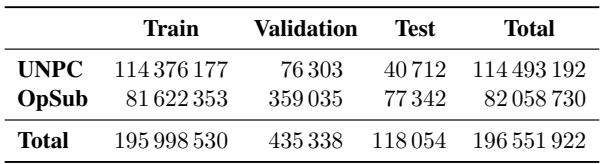

- Same Data: All models were trained on the exact same dataset, a combination of the UNPC (United Nations Parallel Corpus) and OpenSubtitles.

- Same Size: All models utilized 12 layers, 512 hidden dimensions, and 8 attention heads.

- Same Tokenization: A shared vocabulary of 100k BPE (Byte Pair Encoding) pieces.

- Same Compute: All models were trained for 600k steps.

The languages selected for this study were Arabic (AR), Chinese (ZH), English (EN), French (FR), Russian (RU), and Spanish (ES).

The Data Constraint

It is worth noting the rigor of their data selection. To compare translation objectives against monolingual objectives, you need bitexts (sentences aligned in two languages).

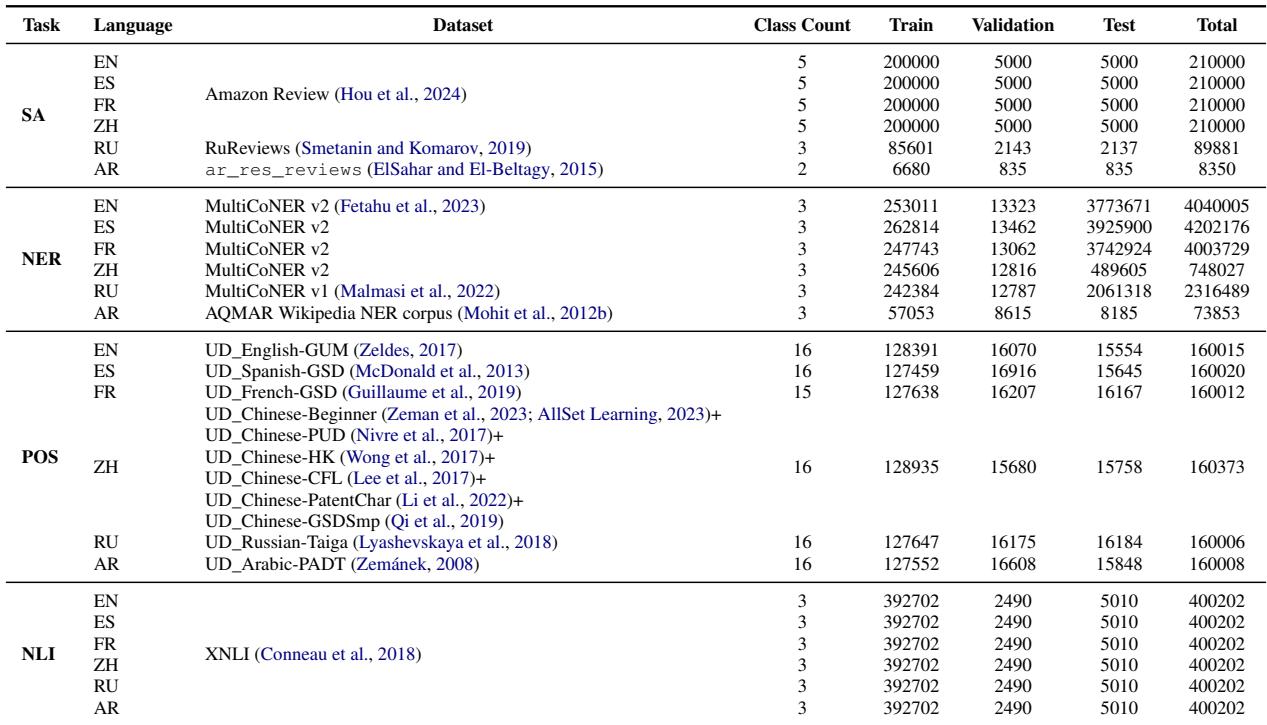

As shown in Table 4, the researchers used a massive amount of sentence pairs—over 196 million total lines. Crucially, they ensured that every document used for the translation models was also available for the monolingual models. If a document existed in three languages, they greedily assigned it to the least represented language pair to balance the data, ensuring no model had an unfair data advantage.

The Contestants: Five Models, Two Categories

The researchers categorized their models into Double-Stack (Encoder-Decoder architectures like BART or T5) and Single-Stack (Encoder-only like BERT or Decoder-only like GPT).

Let’s look at the five specific objectives they compared.

1. Double-Stack Models (Encoder-Decoder)

These models consist of two main blocks: an encoder that processes the input and a decoder that generates the output.

- 2-LM (BART Denoising): This uses the standard BART objective. The input text is corrupted (words are masked or shuffled), and the model must reconstruct the original clean text. It operates within a single language at a time.

- 2-MT (Machine Translation): The model is given a sentence in a source language (e.g., French) and must generate the translation in a target language (e.g., English). This provides a strong, explicit cross-lingual signal.

2. Single-Stack Models

These models consist of just one transformer stack.

- MLM (Masked Language Modeling): An Encoder-only model (like BERT). Some tokens in the input are hidden with a

[MASK]token, and the model must guess what they are based on the context. - CLM (Causal Language Modeling): A Decoder-only model (like GPT). The model reads a sequence and predicts the next word. It can only “see” words to the left of the current position.

- TLM (Translation Language Model): This is a variation of the CLM. The model is fed a sentence and its translation concatenated together. It then performs causal language modeling (predicting the next word) across this long, dual-language sequence.

Visualizing the Objectives

The difference between these objectives can be abstract, so let’s look at exactly what the models see during training.

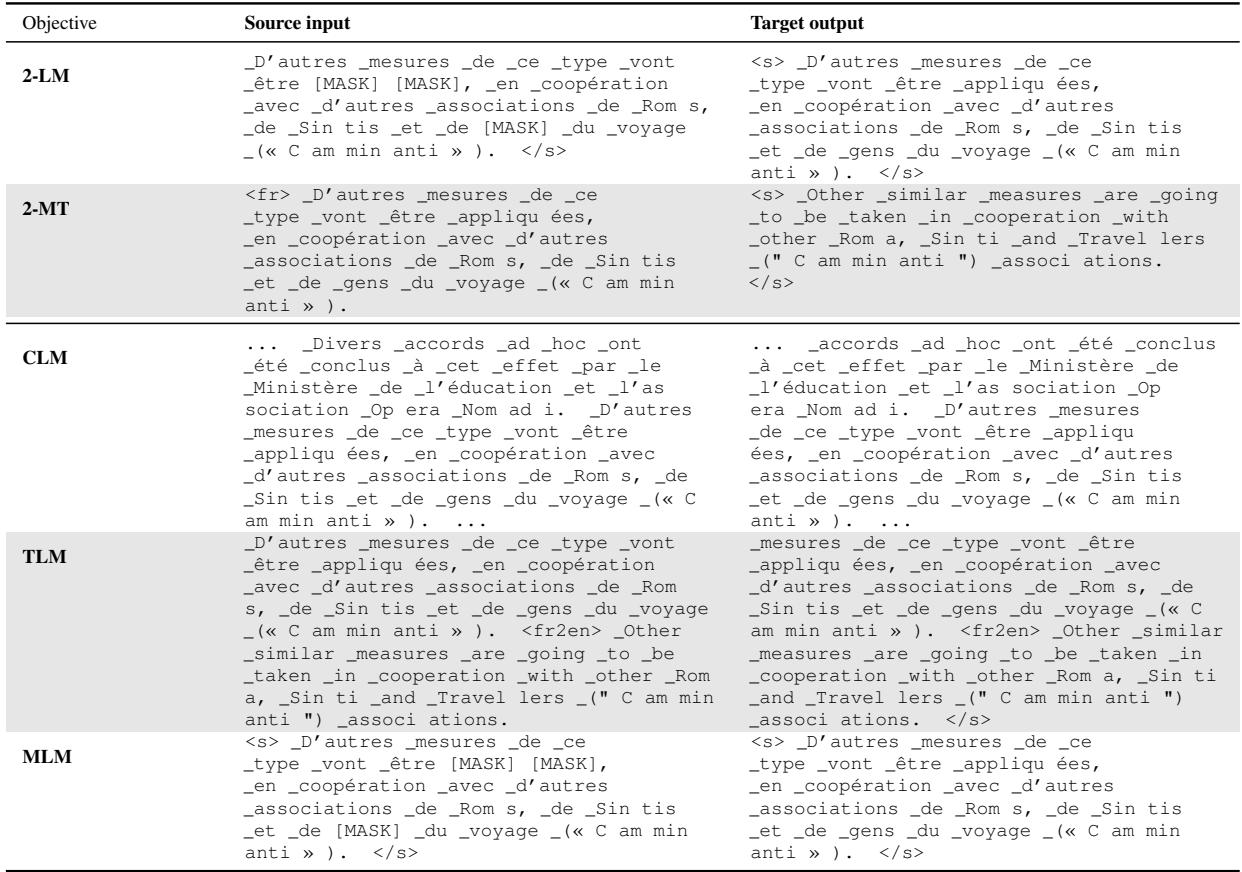

Table 3 provides a concrete example of how the same underlying data is formatted for each objective:

- 2-LM: Notice how the input has

[MASK]tokens. The target output is the clean, original French sentence. - 2-MT: The input is French; the target output is English. The model must understand the meaning to succeed.

- MLM: Similar to 2-LM, but this is an encoder-only architecture. It predicts the masked words directly rather than generating a whole new sequence.

- CLM: The model reads a continuous stream of text and predicts the next token.

- TLM: The model reads the French sentence, then a separator token, then the English sentence, predicting tokens one by one.

Evaluation Strategy: Probing vs. Fine-tuning

How do you determine which model is “better”? The researchers used two distinct evaluation methods on downstream tasks (Sentiment Analysis, NER, POS Tagging, and NLI):

- Probing: You “freeze” the pretrained model. You do not allow the model’s weights to change. You only train a small classifier on top of the model’s output.

- What this tests: The raw quality of the representations the model learned during pretraining. Does the model naturally understand sentiment or grammar without extra help?

- Fine-tuning: You allow all the parameters in the model to update during training on the new task.

- What this tests: The model’s adaptivity. Can the model effectively reconfigure itself to solve a specific problem?

Key Results

The results revealed a fascinating interplay between architecture and objective. It turns out there is no single “best” objective—it depends entirely on what architecture you are using.

Finding 1: For Encoder-Decoders, Translation is King

When looking at the Double-Stack models (the BART-style architectures), the results were decisive.

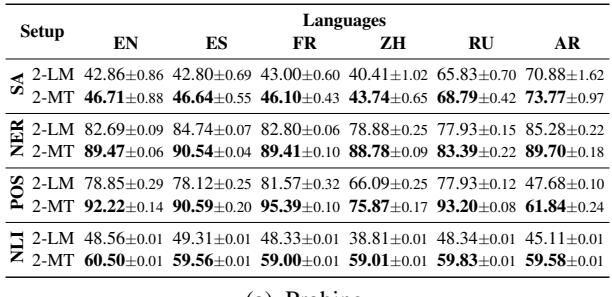

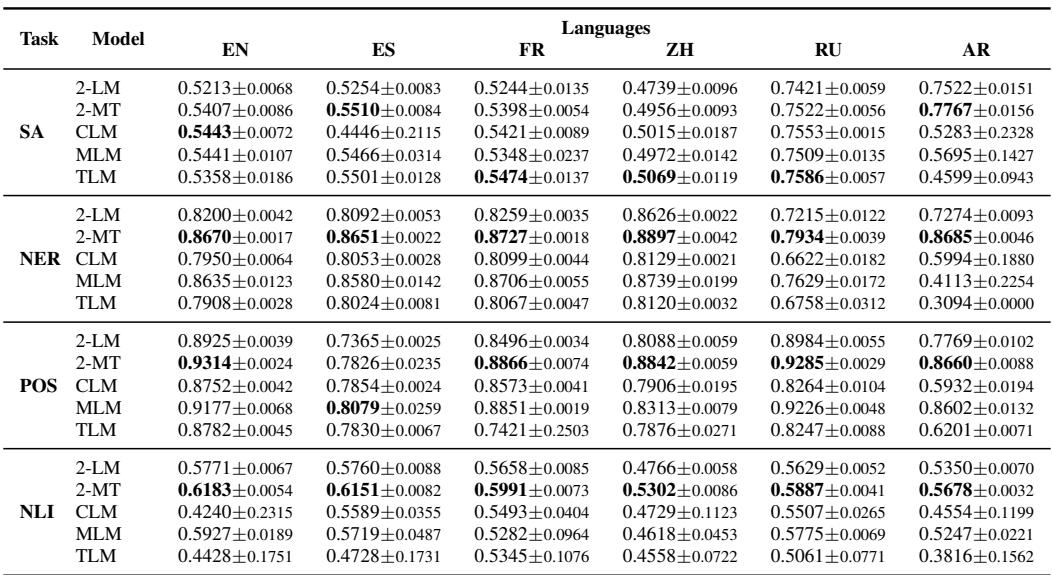

Table 1 shows the accuracy for probing experiments. The 2-MT model (trained on translation) consistently outperforms the 2-LM model (trained on denoising) across almost every language and task.

- Interpretation: The explicit signal of translation forces the encoder-decoder to align representations of different languages more effectively than simply denoising text. If you are building an encoder-decoder model for multilingual tasks, translation data is incredibly valuable.

Finding 2: The Single-Stack Surprise

The results for Single-Stack models were more nuanced and challenged conventional wisdom.

Table 2 highlights the probing accuracy for single-stack models.

- The CLM Shock: The Causal Language Model (GPT-style) performed surprisingly well in probing scenarios, often beating the Masked Language Model (BERT-style). This is counter-intuitive because BERT models are bidirectional (they see the whole sentence), which usually helps with understanding tasks like NER or POS tagging.

- The TLM Disappointment: Despite having access to translation data, the TLM (Translation Language Model) did not dominate the single-stack category. It did not consistently outperform the standard CLM.

Finding 3: Fine-Tuning Levels the Playing Field

While probing tells us about the raw knowledge of the model, fine-tuning tells us about its practical utility.

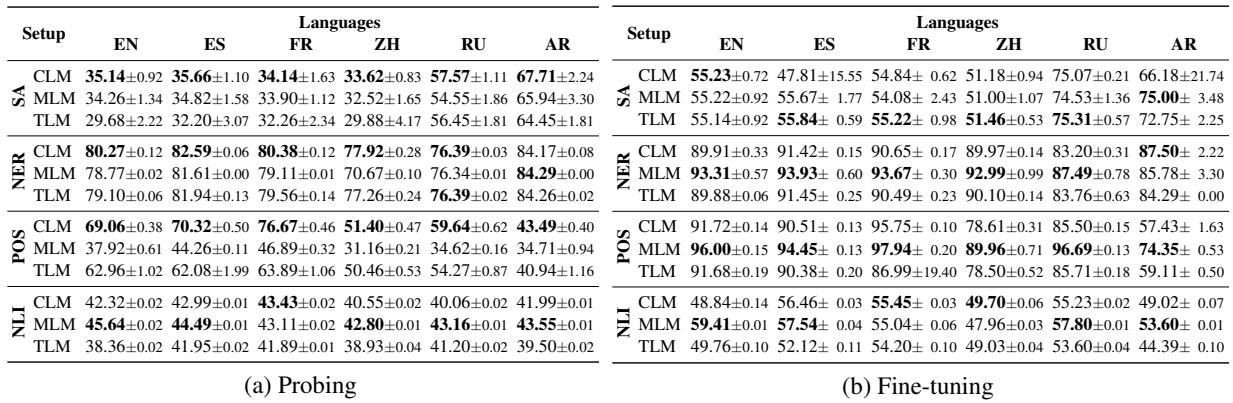

Table 7 shows the Macro F1 scores after fine-tuning. Here, the landscape shifts:

- MLM Resurgence: While the MLM (BERT) struggled in probing compared to CLM, it becomes highly effective when fine-tuned, particularly for Part-of-Speech (POS) tagging and Named Entity Recognition (NER).

- 2-MT Dominance: The Machine Translation model (2-MT) remains a top performer even after fine-tuning. It achieves the highest scores in many categories, suggesting that the “translation intuition” it learned during pretraining provides a robust foundation that is easy to adapt to specific tasks.

Why Does This Matter?

This paper offers several critical takeaways for students and researchers in NLP:

1. Architecture Dictates Objective

You cannot simply say “Translation is the best pretraining objective.” It is the best objective if you are using an Encoder-Decoder architecture. If you are using a Decoder-only architecture, standard Causal Language Modeling might be sufficient. This coupling between architecture and objective is often overlooked in broader discussions.

2. The Power of Translation

The most significant finding is the strength of the 2-MT model. In the era of “Foundation Models” trained on massive piles of monolingual web text (CommonCrawl), this research suggests we might be under-utilizing parallel data. A model that learns to translate is forced to learn semantics. It cannot just rely on statistical patterns of which words sit next to each other; it has to understand that “bank” in a financial context translates differently than “bank” in a river context.

3. The Importance of Control

Finally, this paper serves as a tutorial on good experimental design. By rigorously controlling the dataset size and overlap (as seen in Table 4 and Table 5 below), the authors ensured that their conclusions were mathematically valid.

If they had simply compared a pre-downloaded mBERT against a pre-downloaded mT5, the results would have been meaningless because the training data would have been different.

Conclusion

The researchers conclude that Multilingual Translation is a highly effective, yet under-explored, pretraining objective. While the industry races toward larger and larger monolingual models, this paper suggests that the explicit cross-lingual signal found in translation tasks builds superior representations, particularly for Encoder-Decoder models.

For students designing their own models: if you have access to parallel data (bitexts), using a translation objective might give your model a “semantic boost” that simple denoising or language modeling cannot match. The future of multilingual AI might not just be about reading more text, but about learning to translate it.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2407.15489/images/cover.png)