Imagine you have trained a massive Large Language Model (LLM) on the entire internet. It’s brilliant, capable, and fluent. But there’s a problem: it memorized the private medical records of a random citizen, or it knows the copyrighted plot twists of a book series you no longer have the rights to use.

You can’t simply hit “delete” on a specific file inside a neural network. The information is diffused across billions of parameters. Retraining the model from scratch effectively removes the data, but it costs millions of dollars and takes months.

This is the challenge of Machine Unlearning.

In this post, we are going to dive deep into a fascinating research paper titled “Revisiting Who’s Harry Potter: Towards Targeted Unlearning from a Causal Intervention Perspective.” The authors revisit a quirky but promising method called “Who’s Harry Potter” (WHP) and reconstruct it using the rigorous mathematics of Causal Inference. By doing so, they not only explain why the method works but also drastically improve it, allowing us to surgically remove specific knowledge from an LLM without giving it a lobotomy.

The Problem: Targeted Unlearning

Before we fix the model, we must define what “fixing” means. In the context of LLMs, we are looking for Targeted Unlearning.

Most current attempts at unlearning are blunt instruments. They often use techniques like Gradient Ascent—essentially running training in reverse to maximize the error on the specific data we want to forget. While this erases the data, it often destroys the model’s ability to speak coherently or causes it to forget unrelated information (a phenomenon known as “catastrophic forgetting”).

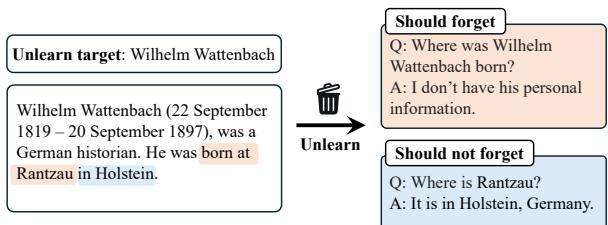

Targeted unlearning has a more nuanced goal. If we want the model to forget a specific person, say, the German historian Wilhelm Wattenbach, we want three things to happen:

- Forget the Target: If asked “Where was Wattenbach born?”, the model should not know.

- Retain Related Knowledge: If the training data mentioned that Wattenbach was born in the town of Rantzau, the model should still know that Rantzau is a town in Germany. It should just forget the link between Wattenbach and Rantzau.

- Maintain General Utility: The model should still be able to write code, summarize poetry, and answer questions about Elon Musk.

As shown in Figure 2, the goal is precise. We want to sever the connection between the entity (Wattenbach) and his biographical facts, without deleting the facts themselves from the model’s “worldview.”

Background: Who is Harry Potter?

To solve this, the researchers looked back at a pioneering method introduced by Microsoft researchers Eldan and Russinovich, famously dubbed “Who’s Harry Potter” (WHP).

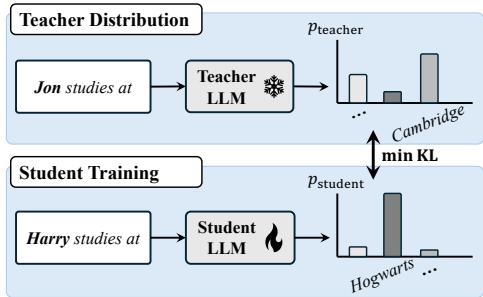

The intuition behind WHP is surprisingly simple. To make an LLM forget Harry Potter, you don’t just punish it for saying “Harry Potter.” Instead, you create a “Teacher” model that has a distorted view of reality. You take the original training text, replace the name “Harry Potter” with a generic name (like “Jon”), and see what the model predicts for “Jon.”

Because the model doesn’t know “Jon” is a wizard who goes to Hogwarts, it predicts generic completions. You then train a “Student” model (the one you want to unlearn) to mimic this generic behavior whenever it sees “Harry Potter.”

Figure 1 illustrates this dynamic. The Teacher distribution (top) sees the name “Jon” and predicts a generic location (like Cambridge). The Student (bottom) originally associates “Harry” with “Hogwarts.” The unlearning process forces the Student to align its probability distribution with the Teacher.

While WHP was a breakthrough, it was heuristic—a clever trick without a solid mathematical explanation. Because of this, it had flaws. The unlearned models often hallucinated or gave inconsistent answers. The authors of the paper we are discussing today decided to formalize this process using Causal Intervention, turning a “clever trick” into a principled algorithm.

The Core Method: Unlearning via Causal Intervention

This is the heart of the paper. To understand how to remove knowledge, we have to model how the knowledge got there in the first place. The authors propose a Structural Causal Model (SCM).

1. The Causal Graph

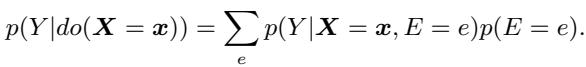

Let’s imagine the process of generating a sentence about a person as a causal graph. We have three variables:

- \(X\) (Input): The prompt given to the LLM (e.g., “Wilhelm Wattenbach was born in…”).

- \(Y\) (Output): The completion generated by the LLM (e.g., “…1819”).

- \(E\) (Knowledge): The underlying “fact” or entity knowledge stored in the model (e.g., the biographical data of Wattenbach).

In a standard LLM generation, the Knowledge (\(E\)) acts as a confounder. It influences both the Input (we ask about Wattenbach because he exists) and the Output (we get the correct date because the model knows it).

In Figure 3, look at the arrows. There is a direct path from \(X\) to \(Y\) (language structure) and an indirect path through \(E\) (factual knowledge). The “link” we want to break is the influence of \(E\) on \(Y\).

2. The Intervention (\(do\)-calculus)

In causal inference, if we want to see what happens when we remove the influence of a variable, we use the \(do\)-operator. We want to estimate \(P(Y | do(X=x))\).

Conceptually, asking for \(P(Y | do(X=x))\) means: “What would the model predict for this input \(x\), if we forced the input to be \(x\) but severed the connection to the specific entity \(E\)?”

If we sever the link to the specific knowledge of Wattenbach, the model should rely only on the direct path—the general statistics of the English language. It should predict whatever is most likely for any generic person, not specifically for Wattenbach.

Mathematically, this uses the backdoor adjustment formula:

This equation says: To get the “unlearned” distribution, we sum over all possible values of knowledge \(e\) (e.g., the biographies of all random people), weighted by their probability.

3. Creating “Parallel Universes” with Name Swapping

Here is the brilliant practical implementation of that math. We can’t access the abstract variable \(E\) inside the black box of a neural network. However, we can simulate different values of \(E\) by changing the name of the subject.

If we replace “Wilhelm Wattenbach” with “Alan Turing” in the input, we are effectively sampling a different \(e\) (different knowledge). If we replace it with “Jon Doe,” we sample another.

The authors propose a three-step process to construct the Teacher Distribution that the Student should mimic:

Step 1: Name Change (The Counterfactual Input) Take the unlearning document (e.g., Wattenbach’s Wikipedia page). Replace every instance of “Wilhelm Wattenbach” with a different name, say “Paul Marston.”

- Input: “Paul Marston was born in…”

Step 2: Counterfactual Prompting Feed this modified text into the frozen, original LLM. Crucially, explicitly prompt the model to treat this as a bio of Paul Marston. This forces the model to use its internal knowledge of “Paul Marston” (or generic knowledge if the name is unknown) rather than Wattenbach.

Step 3: The Reverse Swap (The Correction) This is a critical innovation over the original WHP method. The model will generate a prediction for Paul Marston.

- Prediction: “…London.” (Because maybe the model thinks Paul Marstons are usually born in London).

- Correction: In the output probability distribution, we take the probability assigned to “Paul” and move it back to “Wilhelm.”

Why swap back? If we don’t, the unlearned model might get confused about who the subject is. We want the model to say, “Wilhelm Wattenbach was born in London” (a generic, incorrect fact), not “Paul Marston was born in London” when asked about Wilhelm.

4. Aggregating Multiple Teachers

The original WHP used just one replacement name. The causal framework suggests we should sum over many \(e\)’s (many different people).

The authors run the procedure above with \(N\) different names (e.g., 20 random names) and average the resulting probability distributions.

- Name 1: Predicts London.

- Name 2: Predicts New York.

- Name 3: Predicts Berlin.

When you average these, you get a “flat” distribution. The model becomes unsure. It doesn’t confidently lie; it just doesn’t know. This simple aggregation step turns out to be the key to preventing hallucinations.

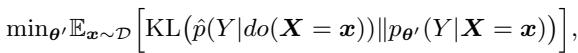

5. Training the Student

Finally, we train the Student LLM (parameterized by \(\theta'\)) to minimize the difference (KL Divergence) between its own predictions and this aggregated Teacher distribution.

This equation essentially says: “Tune the student model \(\theta'\) so that when it sees the original text \(x\), it outputs the same confused, generic probabilities as the Teacher.”

Experiments and Results

To prove this works, the authors constructed a new, rigorous benchmark called WPU (Wikipedia Person Unlearning).

They selected 100 real people from Wikipedia (who were not super-famous celebrities) and created datasets to test:

- Forget QA: Questions about the target.

- Hard-retain QA: Questions about other entities mentioned in the target’s bio.

- General-retain QA: Questions about famous people (like Elon Musk) to ensure general utility.

Performance on WPU

They compared their method (“Ours”) against several baselines:

- GA (Gradient Ascent): Just trying to maximize loss on the target data.

- WHP: The original algorithm.

- Prompting: Just telling the model “Don’t talk about this.”

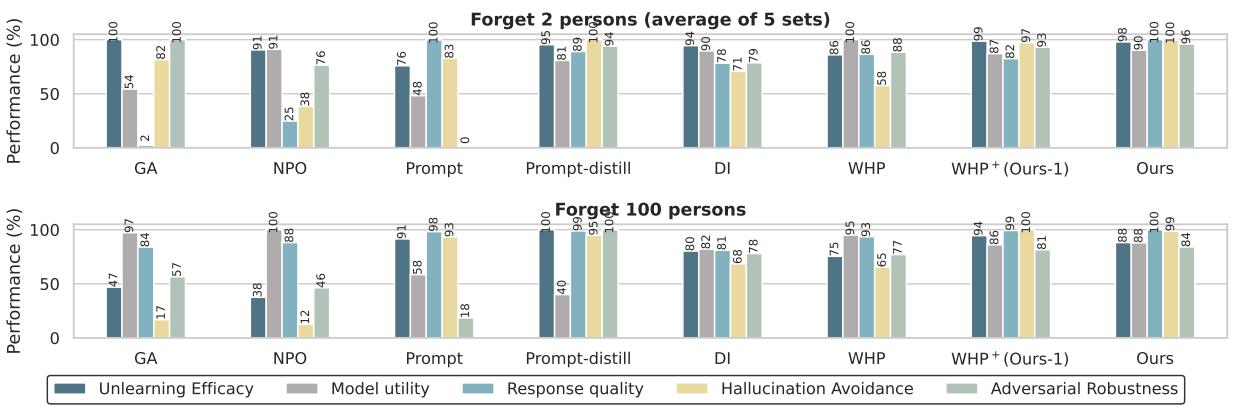

Here is the normalized performance across five critical criteria:

Key Takeaways from Figure 4:

- Unlearning Efficacy (Dark Blue): The proposed method (Ours) is nearly perfect (98%). It truly forgets.

- Response Quality (Cyan): Look at GA (Gradient Ascent). Its response quality drops significantly because maximizing loss often makes the model speak gibberish. The causal method maintains perfect quality.

- Hallucination Avoidance (Yellow): This is the big win. The original WHP (labeled WHP in the chart) struggles here, often making things up. The new method (Ours), thanks to aggregating multiple names, achieves nearly 100% avoidance. It correctly refuses to answer rather than lying.

The TOFU Benchmark

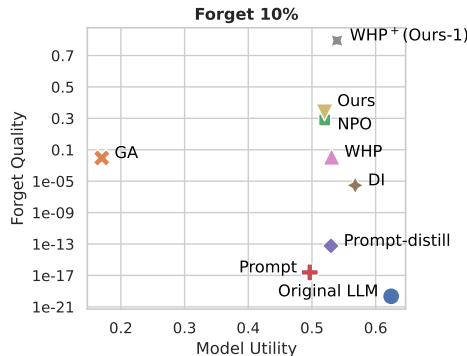

They also tested on the TOFU (Task of Fictitious Unlearning) dataset, which uses fake authors and books. This is a controlled environment where we know exactly what the “Gold Standard” (a model trained from scratch without the data) looks like.

In Figure 5, we want to be in the top-right corner: high Model Utility (smart model) and high Forget Quality (successful unlearning).

- GA (Orange X): High utility, but terrible forget quality (bottom left).

- WHP (Pink Triangle): Better, but still lagging.

- Ours (Gray/Yellow): The causal methods are distinct outliers in the best possible way. They achieve forget quality that rivals the original model while maintaining utility.

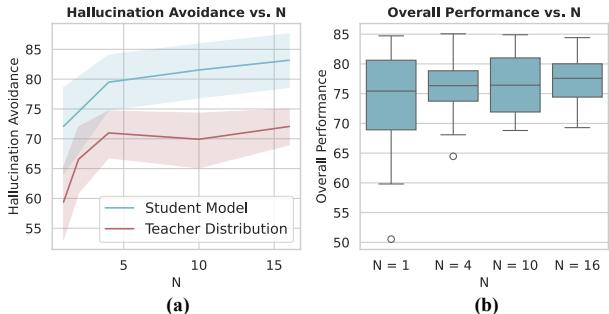

Why does “N” matter?

Recall that the method involves averaging the teacher distribution over \(N\) replacement names. Is this necessary?

The ablation study in Figure 6 shows the impact of increasing \(N\) (the number of replacement names).

As \(N\) increases (x-axis), the Hallucination Avoidance (red line in chart (a)) climbs steadily. If you only use one name (like the original WHP), the model might hallucinate specific details from that one replacement name. By averaging 10 or 15 names, the specific details cancel out, leaving the model with a “flat” knowledge base regarding the target. It effectively learns that it doesn’t know.

Conclusion & Implications

This research bridges the gap between empirical “hacks” and theoretical understanding. By viewing the unlearning problem through the lens of Causal Intervention, the authors successfully explained why replacing names works: it is a practical way to estimate the counterfactual distribution where the specific entity knowledge is removed.

The resulting algorithm is:

- Effective: It scrubs the specific data.

- Surgical: It leaves related concepts intact (Targeted Unlearning).

- Safe: It reduces the hallucinations that plagued previous methods.

As regulations around AI privacy and copyright tighten (such as the “Right to be Forgotten”), techniques like this will be essential. We cannot retrain GPT-4 every time a user wants their data removed. We need the ability to perform precise, causal surgery on the model’s brain. This paper provides the scalpel.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2407.16997/images/cover.png)