When we read a news article or follow a complex narrative, we don’t process sentences in isolation. We instinctively look for connections. We ask ourselves: Why is the author saying this? What question does this sentence answer regarding the previous one?

This cognitive process is the foundation of a linguistic framework known as Question Under Discussion (QUD). It treats discourse as a hierarchy of questions and answers. While humans do this naturally, teaching machines to parse these structures is notoriously difficult. Existing models often struggle to generate questions that make sense within the context or fail to link sentences correctly.

In this post, we will explore QUDSELECT, a novel framework introduced by researchers from UCLA and Peking University. This paper proposes a method to improve QUD parsing by moving away from rigid pipelines and toward a “selective decoding” strategy that mimics how we evaluate the quality of a question.

Understanding the Problem: What is QUD?

Before diving into the architecture, we need to understand the task. QUD parsing is a form of discourse analysis. The core idea is that every sentence in a text (except the very first one) can be viewed as an answer to an implicit question triggered by a sentence in the prior context.

Let’s break down the terminology:

- Anchor Sentence: The sentence in the previous context that triggers a question.

- Question (QUD): An implicit question connecting the anchor to the current sentence.

- Answer Sentence: The current sentence being processed, which answers the generated question.

The Three Golden Rules of QUD

For a QUD structure to be valid, it isn’t enough to just generate any question. Theoretical linguistics defines three specific criteria that must be met:

- Answer Compatibility: The “Answer Sentence” must actually answer the question.

- Givenness: The question should not introduce new information (hallucinations) or “leak” the answer. It should only contain concepts present in the context or common knowledge.

- Anchor Relevance: The question must be relevant to the anchor sentence. It should feel like a natural follow-up to what was just said.

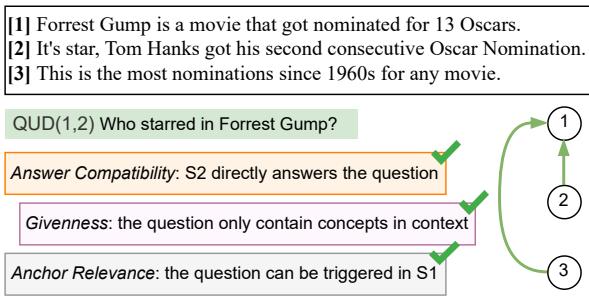

To visualize this, look at the example below involving a text about the movie Forrest Gump.

In Figure 1, notice how Sentence 3 (“This is the most nominations…”) connects to Sentence 1 (“Forrest Gump is a movie…”). The implicit question is “Which movie has the most Oscar nominations?” This structure reveals the logical flow of the argument. The diagram also highlights the validity checks: Does S2 answer the question? Yes. Does the question rely only on known context? Yes. Is it relevant to S1? Yes.

The Limitation of Previous Approaches

Prior to QUDSELECT, most attempts to automate this process used a pipeline approach.

- Step 1: Look at the context and predict which sentence acts as the anchor.

- Step 2: Given that anchor, generate a question.

The problem with pipelines is the lack of a “holistic view.” If the model picks a bad anchor in Step 1, Step 2 is doomed. Furthermore, standard language models (LLMs) often generate questions that sound fluent but fail the specific QUD criteria—for example, they might include details that haven’t been revealed yet (violating Givenness).

The QUDSELECT Framework

The researchers propose a solution that integrates these distinct steps and explicitly enforces the theoretical criteria. Their framework, QUDSELECT, consists of two main innovations: Joint Training via Instruction Tuning and Selective Decoding.

Innovation 1: Joint Training

Instead of separating anchor prediction and question generation, QUDSELECT trains the model to do both simultaneously. The researchers reformulate the task as an instruction-tuning problem.

They feed the model the context and the target “Answer Sentence.” The instruction asks the model to output a formatted string:

“Sentence [Answer ID] is anchored by sentence [Anchor ID], answering the question of [Question].”

By forcing the model to predict the anchor and the question in a single breath, the model learns the dependency between finding a good trigger and asking a good question.

Innovation 2: Selective Decoding

This is the core contribution of the paper. Even with joint training, an LLM might still generate a suboptimal question. To fix this, the authors introduce a select-then-verify inference strategy.

Instead of taking the single most likely output from the model, QUDSELECT generates multiple candidates and scores them against the three theoretical criteria we discussed earlier.

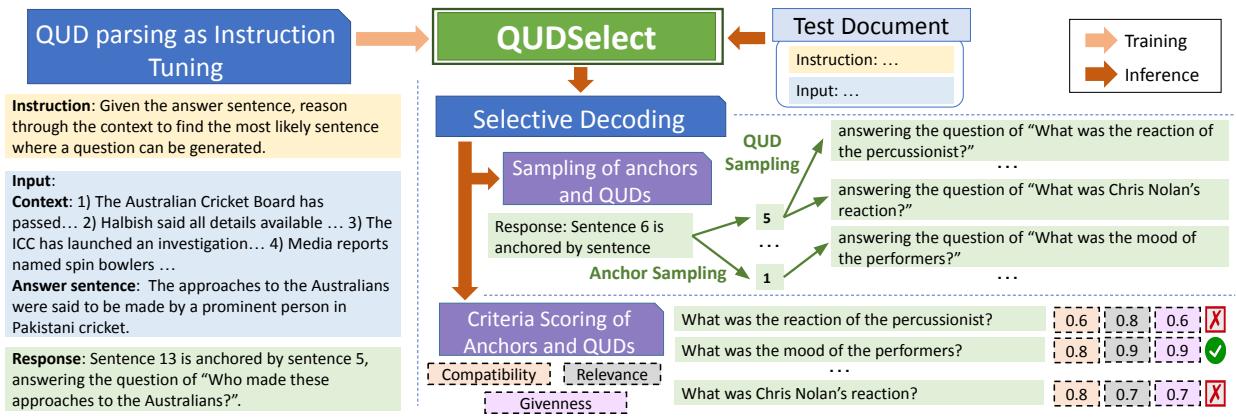

As shown in Figure 2, the process works like this:

- Sampling: The model uses beam search to generate multiple candidate pairs of (Anchor, Question). It samples different potential anchors and, for each anchor, different potential questions.

- Criteria Scoring: Each candidate pair is passed through three specific scoring functions (which we will detail below).

- Selection: The scores are summed, and the candidate with the highest total score is selected as the final QUD.

How are the Criteria Scored?

The researchers needed a way to automate the “Golden Rules” without human intervention during inference. They implemented clever, training-free scorers for each criterion:

- Answer Compatibility Scorer:

- Method: They treat this as a Natural Language Inference (NLI) task.

- Implementation: Using an off-the-shelf NLI model, they check the probability that the Answer Sentence entails the Question. If the answer implies the question is valid, the score is high.

- Givenness Scorer:

- Method: Overlap measurement.

- Implementation: They compare the content words (nouns, verbs, etc.) in the Question against the Context. If the question contains words that don’t appear in the context (and aren’t common stop words), it’s likely hallucinating or leaking the answer. The score is based on the percentage of words grounded in the context.

- Anchor Relevance Scorer:

- Method: Focus overlap.

- Implementation: They extract the “focus” of the Question (usually the main noun phrase) and check for word overlap with the Anchor sentence. If the question asks about something mentioned in the anchor, it is relevant.

Experiments and Results

To validate this framework, the authors tested QUDSELECT on the DCQA dataset, a standard benchmark for discourse comprehension containing news articles and questions. They applied their framework to open-source models (LLaMA-2-7B, Mistral-7B) and closed-source models (GPT-4).

Performance Metrics

The evaluation was rigorous, using both automatic metrics (classifiers trained to judge QUD quality) and human evaluation (expert annotators).

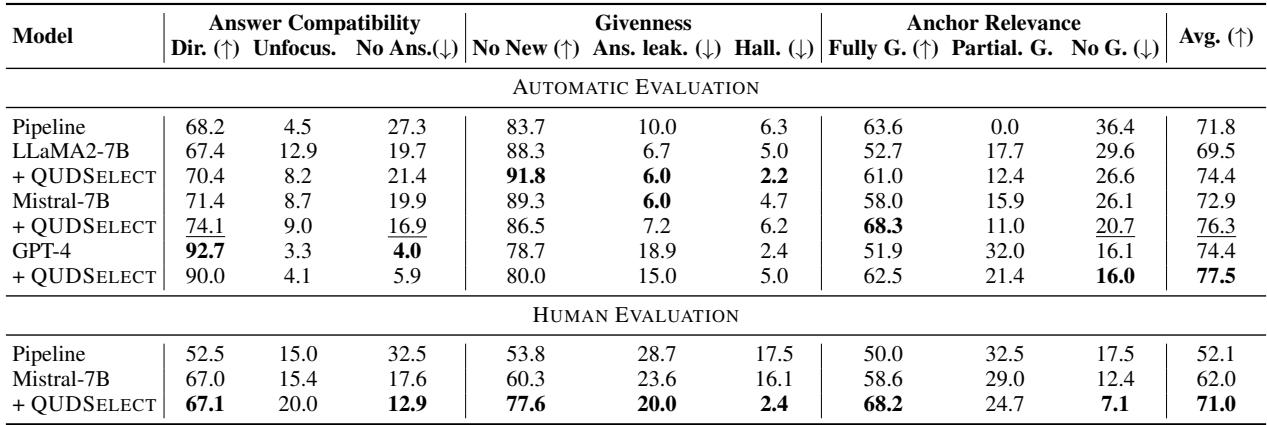

The results were impressive. As seen in Table 1 below, QUDSELECT significantly outperforms the baseline pipeline approaches and standard prompting methods.

Key Takeaways from the Results:

- Beat the Pipeline: In human evaluation, the Mistral-7B model equipped with QUDSELECT scored 71.0%, compared to just 52.1% for the Pipeline baseline.

- Better than GPT-4: Interestingly, the open-source Mistral model with QUDSELECT approached or exceeded the performance of standard GPT-4 prompting in several metrics, proving that a smaller model with a better decoding strategy can punch above its weight.

- Consistency: The improvements are visible across all three criteria: Answer Compatibility, Givenness, and Anchor Relevance.

Does Sampling More Candidates Help?

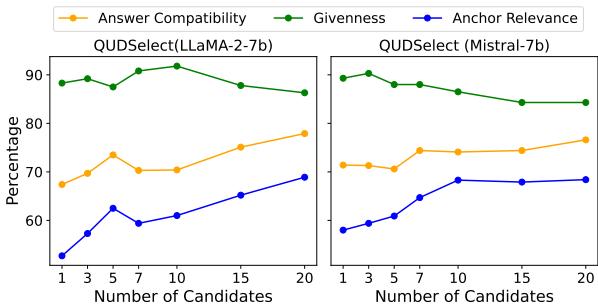

One might ask: How many candidates do we need to sample to get a good result? The researchers conducted a hyperparameter analysis, varying the number of candidates (\(k\)) from 1 to 20.

Figure 3 reveals a clear trend. As the number of candidates increases, the Answer Compatibility (orange line) and Anchor Relevance (blue line) steadily improve.

There is a slight trade-off with Givenness (green line), which dips slightly as \(k\) increases. The authors suggest that this is a minor cost for the significant gains in relevance and answerability. They settled on \(k=10\) as a sweet spot for their main experiments.

Qualitative Analysis: Seeing the Difference

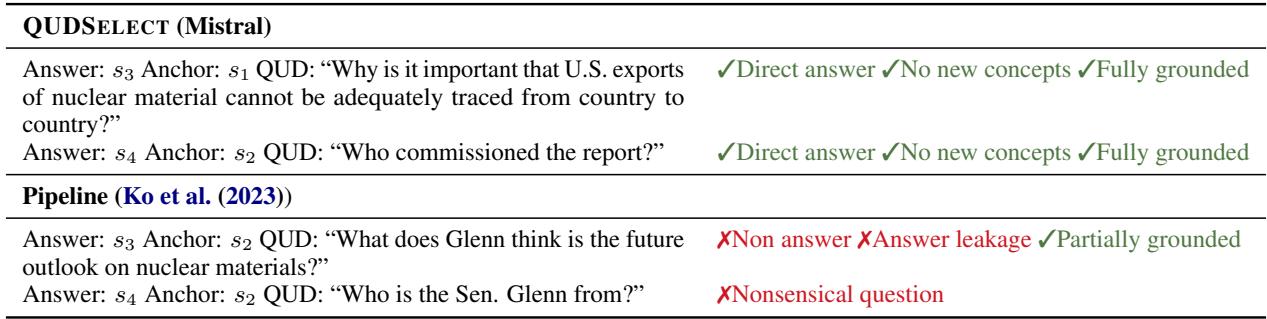

Numbers are great, but examples tell the story. Let’s look at a direct comparison between QUDSELECT and a standard Pipeline model on a real news snippet.

In Table 2, we see a clear failure mode of the Pipeline method.

- Pipeline Error: For sentence \(s_3\), the Pipeline model generates “What does Glenn think…?” The annotators marked this as “Non answer” and “Answer leakage.” It essentially hallucinated information about “Glenn” (who appears in sentence 2) even though the anchor was sentence 2, but the resulting question didn’t fit the answer in sentence 3 well.

- QUDSELECT Success: For the same sentence, QUDSELECT generated “Why is it important that U.S. exports…?” This question is directly answered by the text, uses only known concepts, and is fully grounded.

This comparison highlights how the scoring criteria filter out “hallucinated” or irrelevant questions that standard models often produce.

Conclusion and Implications

The QUDSELECT paper demonstrates a vital lesson for NLP researchers and students: Model architecture isn’t everything; inference strategy matters.

By reformulating QUD parsing as a joint task and applying Selective Decoding, the authors achieved state-of-the-art results without needing a massive model. They showed that we can “guide” LLMs to adhere to theoretical linguistic constraints (Answer Compatibility, Givenness, Relevance) by generating multiple options and algorithmically selecting the best one.

Why does this matter?

Understanding discourse structure is the next frontier for NLP. If computers can understand the questions that link sentences together, they can:

- Summarize better: By understanding the main points of discussion.

- Fact-check more accurately: By verifying if a claim actually answers the implied question of the context.

- Generate more coherent text: By ensuring every generated sentence follows logically from the previous one.

QUDSELECT offers a robust, theoretically grounded path toward these goals, proving that sometimes, the best way to get the right answer is to generate a few options and check your work.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2408.01046/images/cover.png)