If you have used a search engine recently, you have likely benefited from dense retrieval. Unlike the search engines of the 90s that looked for exact keyword matches, modern systems try to understand the meaning behind your query. They turn your words into a list of numbers (a vector) and look for documents with similar vectors.

For years, the backbone of this technology has been models like BERT and T5. They are excellent at what they do, but they have hit a ceiling. They struggle with long documents, they often fail when presented with data from a new domain (like legal or medical documents), and they require massive amounts of labeled data to train.

But recently, we have witnessed the explosion of Large Language Models (LLMs) like Llama, Qwen, and GPT. We know they are good at generating text, but are they good at finding it?

In the paper “Large Language Models as Foundations for Next-Gen Dense Retrieval: A Comprehensive Empirical Assessment,” researchers conducted a massive study to answer this question. They tested over 15 different models to see if LLMs could replace traditional encoders. The results are fascinating and suggest a paradigm shift in how we build search systems.

In this post, we will break down their methodology, the mathematics behind it, and the six key experiments that prove why bigger might actually be better.

The Bottleneck of Traditional Retrieval

Before we dive into the solution, let’s understand the problem.

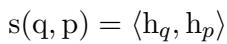

In Dense Retrieval (DR), the goal is to map a user’s query (\(q\)) and a candidate document (\(p\)) into a shared “embedding space.” If the query and the document are semantically similar, their vectors should be close together in this space.

To calculate this “closeness,” we typically use a similarity score. The math is straightforward: we take the embedding of the query (\(h_q\)) and the embedding of the document (\(h_p\)) and calculate the inner product (or dot product).

For years, the standard way to get these \(h\) vectors was using BERT. BERT processes a sequence of text tokens (\(T\)) and outputs a vector for every token. To get a single vector representing the whole sentence, we usually take the vector corresponding to the special [CLS] (classification) token at the start of the sentence.

While effective, BERT-based models are relatively small (usually under 500 million parameters). They lack the “world knowledge” required to understand complex instructions or generalize to topics they weren’t explicitly trained on.

The Core Method: Turning LLMs into Retrievers

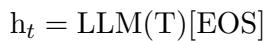

The researchers propose replacing BERT with massive Decoder-only LLMs (like Llama-2 or Qwen). However, there is a structural difference. BERT reads text bidirectionally (looking at the whole sentence at once). LLMs are causal; they read left-to-right, predicting the next word.

Because of this causal attention mechanism, the “meaning” of the sentence accumulates at the very end. Therefore, instead of using the start token, the researchers extract the embedding from the End of Sentence ([EOS]) token.

The Training Process

How do you teach an LLM—which is designed to write stories or code—to become a search engine? You use Contrastive Learning.

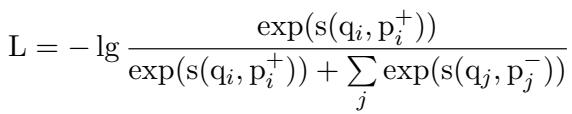

The team utilized the InfoNCE loss function. The idea is simple: given a query \(q_i\), the model should maximize the similarity score with the positive document \(p_i^+\) (the correct answer) while minimizing the score with a set of negative documents \(p_j^-\) (wrong answers).

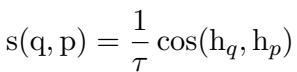

To make the scoring even more precise, they utilized a temperature-scaled cosine similarity. The temperature parameter (\(\tau\)) helps control the sharpness of the probability distribution, making the model more discriminative.

With the math established, the researchers set out to test over 15 backbone models ranging from small 100M parameter models to massive 32B parameter giants. They focused on two main questions:

- Do LLMs offer specific benefits over non-LLMs?

- Does size (parameters) and pre-training data volume matter?

Let’s look at the results.

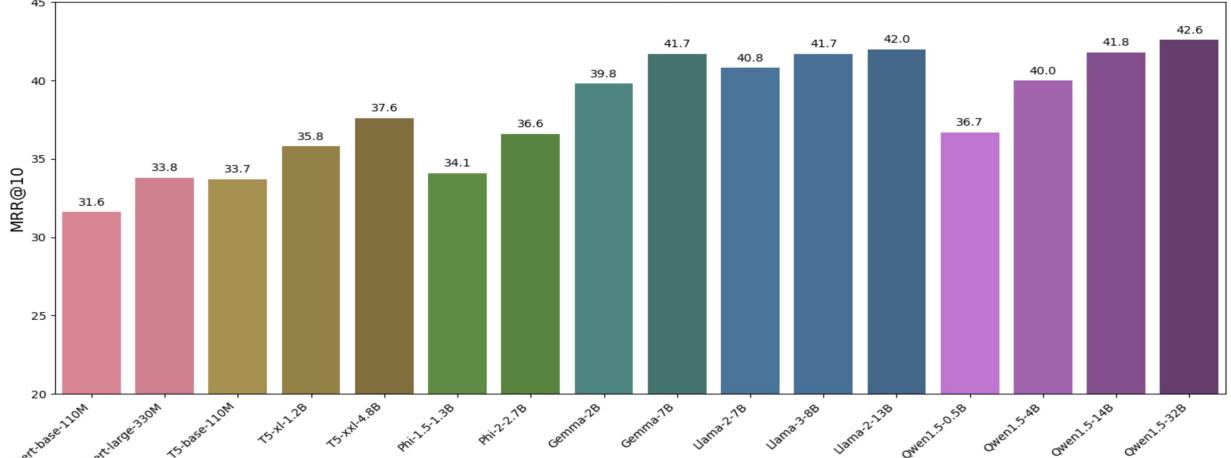

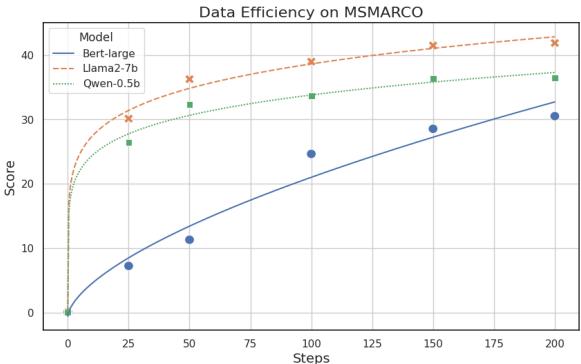

Experiment 1: In-Domain Accuracy

The first test was on the “home turf” of retrieval: the MS MARCO dataset. This is a massive collection of real web search queries. The researchers wanted to know how well these models perform when trained and tested on standard search data.

The comparison included traditional models (BERT, T5) and modern LLMs (Llama, Gemma, Qwen).

As shown in Figure 1 above, there is a clear trend: scaling up improves performance.

Look at the Qwen1.5 series (the purple bars). The tiny 0.5B model achieves a score of roughly 36.7. As you scale up to 4B, 14B, and finally 32B, the performance climbs steadily to 42.6.

Perhaps the most striking finding is that LLMs consistently outperform non-LLMs. Even the smaller LLMs (like Gemma-2B) perform better than the largest traditional models (like T5-xxl), despite having fewer parameters. This suggests that the high-quality pre-training data LLMs see (trillions of tokens) makes them fundamentally better at understanding language nuances than the older BERT generation.

For those interested in the raw numbers, the table below details the specific metrics (NDCG@10 and MRR@10) for every model tested.

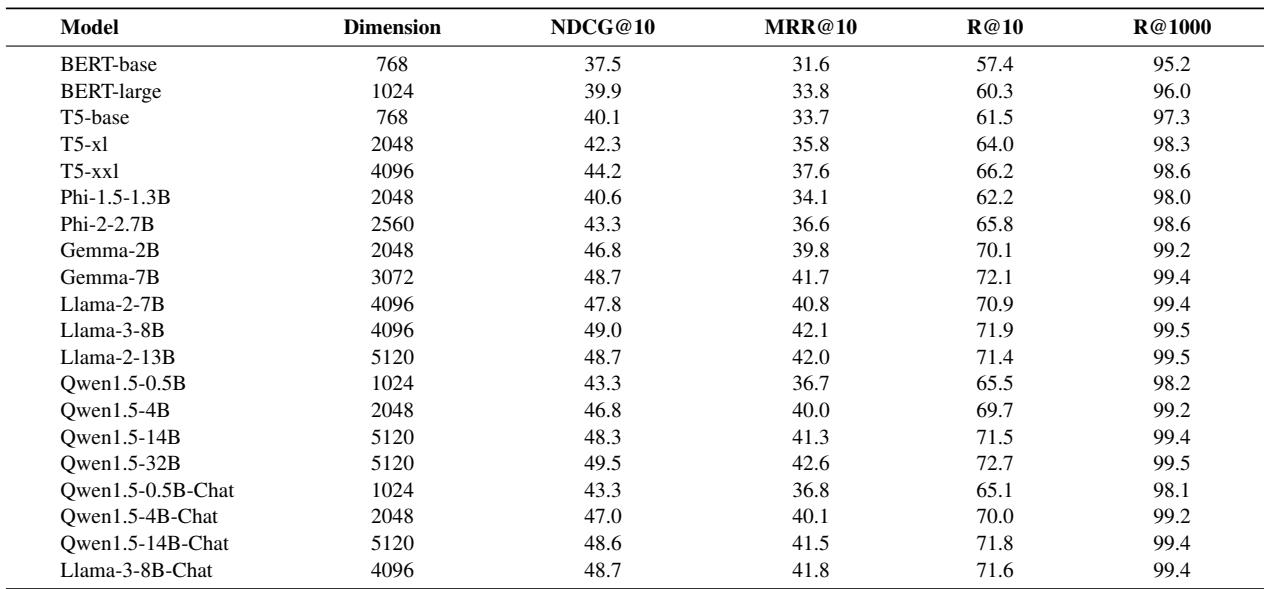

Experiment 2: Data Efficiency

One of the biggest complaints about deep learning is the need for massive labeled datasets. Can LLMs learn faster with less data?

The researchers tracked the performance of three models—BERT-large, Qwen-0.5B, and Llama-2-7B—over the course of their training steps.

Figure 2 illustrates a massive gap in learning speed.

- The Blue Line (BERT-large) struggles to climb, requiring many steps to reach a decent score.

- The Orange Line (Llama-2-7B) shoots up almost immediately.

After just 100 training steps, the Llama model is already outperforming the BERT model by a wide margin. This implies that if you have a specialized domain with very little labeled data (e.g., a proprietary internal company database), using a larger LLM backbone will likely yield good results much faster than trying to fine-tune a BERT model from scratch.

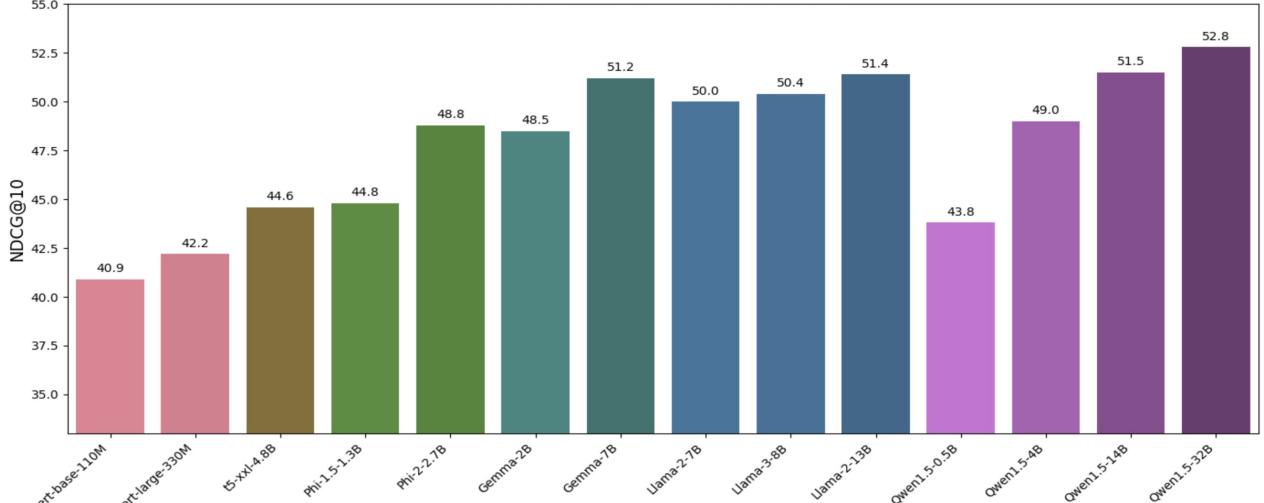

Experiment 3: Zero-Shot Generalization

It’s easy to perform well on data you’ve seen before. The real test of intelligence is Zero-Shot Generalization: performing well on tasks the model has never seen.

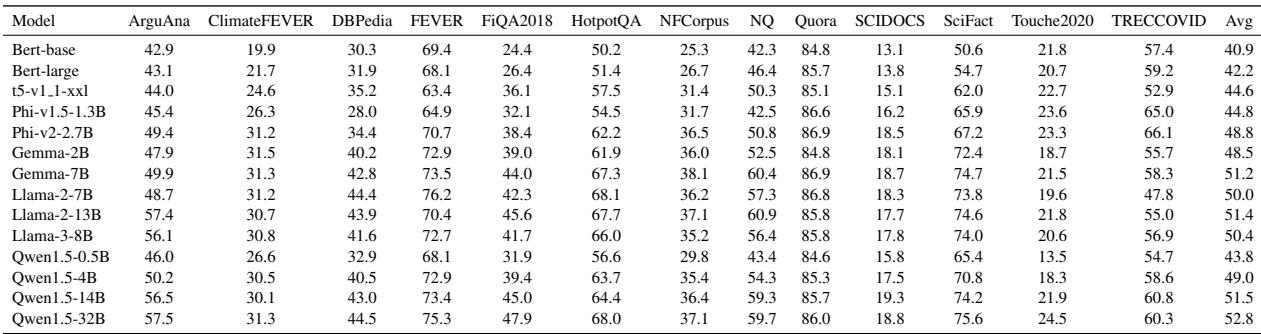

The researchers took models trained on MS MARCO (web search) and immediately tested them on the BEIR benchmark, which includes diverse tasks like retrieving medical papers, financial advice, and fact-checking claims.

Figure 4 shows the average performance across these 13 unseen tasks. The correlation between model size and performance is undeniable here.

- BERT-base scores a 40.9.

- Qwen1.5-32B scores a 52.8.

In the world of zero-shot retrieval, parameters are king. The larger models, which have likely “read” more medical, financial, and technical text during their pre-training, can generalize that knowledge to retrieval tasks without any fine-tuning.

For a granular breakdown of how these models fared on specific datasets like “ClimateFEVER” or “HotpotQA,” refer to the table below:

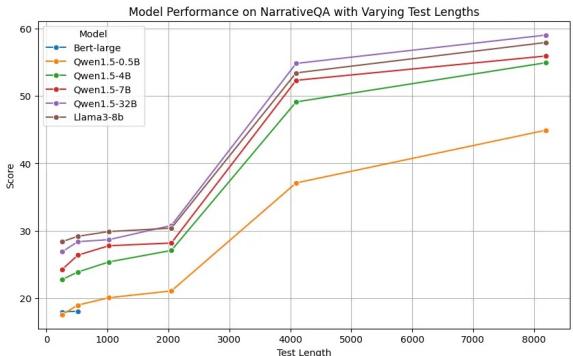

Experiment 4: Lengthy Retrieval

Traditional models like BERT have a hard limit: they can usually only process 512 tokens (words/pieces) at a time. If a document is longer than that, the model has to truncate it, potentially losing crucial information at the end of the text.

LLMs, however, are often trained with massive context windows (4096 tokens or more). The researchers tested if this pre-training capability translates to retrieval by testing on the NarrativeQA dataset, which involves finding answers in long stories.

Figure 3 reveals a distinct advantage for LLMs.

- BERT (Blue Line): Flatlines. It simply cannot handle the longer context.

- LLMs (Purple/Green Lines): As the text gets longer (up to 8000 tokens), the performance of the large LLMs (like Qwen-32B) actually improves or stays distinctively high.

This capability eliminates the need for complex “chunking” strategies that engineers usually have to build to support long-document search.

Experiment 5: Instruction-Based Retrieval

Search is rarely just “keywords.” Sometimes you want a summary; sometimes you want a fact; sometimes you want a counter-argument.

“Instruction-based retrieval” involves prepending a natural language instruction to the query, such as “Given a financial question, retrieve user replies that best answer the question.”

The study found a sharp divide here:

- LLMs: Performance improved when instructions were added. They understood the intent.

- BERT/Non-LLMs: Performance decreased. The instructions acted as “noise,” confusing the model.

This suggests that LLM-based retrievers offer a new level of flexibility. You can customize the search behavior simply by changing the prompt, without retraining the model.

Experiment 6: Multi-Task Learning

Finally, the researchers looked at Multi-Task Learning. In the past, training a single model to do web search, duplicate detection, and fact-checking simultaneously resulted in a “jack of all trades, master of none” scenario—performance usually dropped compared to single-task specialists.

The study found that while performance drops still happen, increasing the model size mitigates this issue. A massive LLM has enough capacity to learn multiple conflicting tasks without “forgetting” how to do the others. This paves the way for a single, universal embedding model that can handle every search task in an organization.

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

The transition from BERT to LLMs in dense retrieval is not just a trend; it is a significant leap forward in capability. The empirical evidence from this paper highlights three major conclusions:

- Size Matters: Increasing parameters and pre-training data volume consistently improves accuracy, data efficiency, and generalization.

- Generalization is the Killer App: The biggest advantage of LLMs isn’t just that they are slightly more accurate on web search, but that they are drastically better at zero-shot tasks and handling long documents.

- Versatility: LLMs can understand instructions and handle multiple tasks, offering a flexibility that previous generations of retrievers simply could not match.

For students and practitioners entering the field of Information Retrieval, the message is clear: the future of search is built on the foundations of Large Language Models. While computational costs are higher, the efficiency in data requirements and the superior performance make LLMs the clear choice for the next generation of search technology.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2408.12194/images/cover.png)