Introduction

We are currently living in the golden age of Large Language Models (LLMs). Systems like GPT-4 have demonstrated an uncanny ability to generate code, write poetry, and even pass bar exams. However, if you have ever tried to use an LLM for a complex logic puzzle or a multi-step deduction task, you may have noticed cracks in the façade.

LLMs act a bit like a student who tries to do complex math entirely in their head. They are brilliant at intuition and pattern matching, but when a problem requires holding five different facts in mind, applying a specific rule, and then using that result to derive a new fact, they often stumble. They hallucinate relationships or lose track of variables.

Today, we are diving deep into a fascinating research paper titled “Symbolic Working Memory Enhances Language Models for Complex Rule Application.” The researchers propose a novel “Neurosymbolic” framework that gives LLMs something they desperately need: a structured, external working memory. By combining the linguistic flexibility of LLMs with the rigid precision of symbolic logic (specifically Prolog), they have created a system that significantly outperforms standard Chain-of-Thought reasoning.

In this post, we will unpack how LLMs fail at complex deduction, what “Symbolic Working Memory” actually looks like, and how this new framework bridges the gap between neural networks and classical logic.

The Problem: When “Thinking Step-by-Step” Isn’t Enough

To understand the solution, we first need to diagnose the problem. Most current techniques for improving LLM reasoning rely on Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting. This is where we ask the model to “think step-by-step.” While effective for many tasks, CoT has a major weakness: it relies entirely on the model’s internal state to track facts.

Reasoning is composed of two main capabilities:

- Rule Grounding: Identifying which rule applies to which facts currently available.

- Rule Implementation: Actually applying that rule to derive a new conclusion.

LLMs are generally good at implementation (generating the text of a conclusion). They are surprisingly bad at grounding—specifically, tracking long lists of facts and figuring out which ones are relevant right now.

This weakness is exposed when information is presented non-sequentially. If you give an LLM a story in perfect chronological order, it does okay. But if you shuffle the facts—a scenario much closer to real-world data retrieval—performance collapses.

As shown in Figure 1 above, the researchers analyzed GPT-4’s performance on the CLUTRR dataset (a kinship reasoning task).

- Pink bars (Sequential): The facts are given in order (A is B’s father, B is C’s sister…). The model performs well.

- Blue bars (Non-Sequential): The facts are shuffled.

Notice the drastic drop-off. For reasoning that requires 5 steps, accuracy drops from over 90% (sequential) to nearly 70% (non-sequential). The model isn’t losing the ability to reason; it’s losing track of the context. It cannot effectively “ground” the rules because it is overwhelmed by the noise of unordered facts.

The Solution: External Working Memory

To solve this, the authors took inspiration from human cognition. When we solve complex logic problems, we don’t just stare at the wall; we write things down. We create a “working memory” external to our brains.

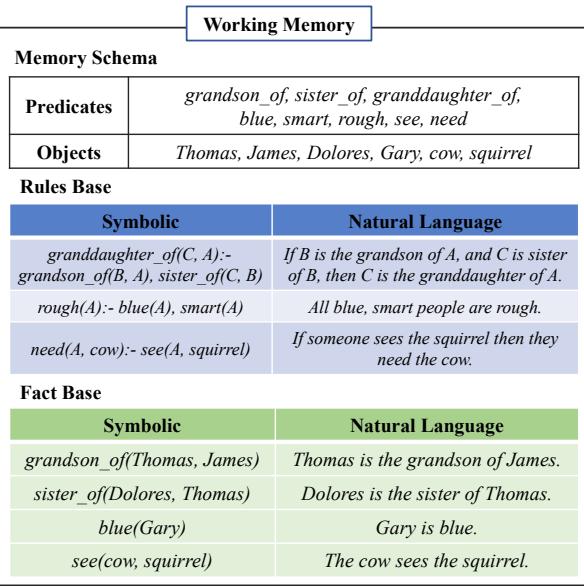

The researchers propose augmenting the LLM with a specialized Working Memory module. Unlike a simple text notepad, this memory is structured. It stores information in two formats simultaneously:

- Natural Language (NL): The readable text (e.g., “Thomas is the grandson of James”).

- Symbolic Form: A logic-friendly format, specifically Prolog predicates (e.g.,

grandson_of(Thomas, James)).

Figure 2 illustrates this dual-storage system.

The Memory Schema (top) acts as a dictionary, defining the allowed objects (people, items) and predicates (relationships like sister_of or needs).

The Rules Base and Fact Base (bottom) store the actual logic puzzle. Notice how every entry has a text version for the LLM and a symbolic version for the logic algorithms. This duality is the core innovation. It allows the system to use precise computer code to find connections (Symbolic) while using the LLM to understand and generate the content (Natural Language).

The Neurosymbolic Framework

So, how does the system actually solve a problem? It uses a cyclical process involving three main stages: Memory Initialization, Rule Grounding, and Rule Implementation.

This is a Neurosymbolic approach. “Neuro” refers to the Neural Network (the LLM), and “Symbolic” refers to the logic programming.

Figure 3 outlines the entire workflow. Let’s break down each phase.

1. Working Memory Initialization

When the system receives a problem (a context and a query), it doesn’t just start guessing. First, it parses the text. The framework breaks the context into sentences and uses an LLM to extract Facts and Rules.

- Input: “Harold bought a dress for his daughter Marie.”

- Extraction: The LLM identifies this as a fact and converts it to the symbolic form

father_of(Harold, Marie)(derived from the context of buying a dress for a daughter).

Crucially, the system builds a Memory Schema dynamically. If it encounters a new relationship, like “roommate_of,” it adds it to the schema to ensure consistent naming throughout the reasoning process.

2. Symbolic Rule Grounding (The “Symbolic” Part)

This is where the framework diverges from standard LLM prompting. Instead of asking the LLM “Which rule applies next?”, the system uses Symbolic Rule Grounding.

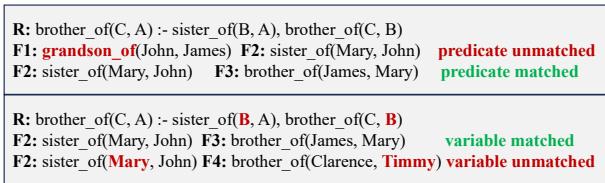

Because the facts and rules are stored as symbols (e.g., sister_of(A, B)), the system can run a deterministic algorithm to check for matches. It performs two types of matching:

- Predicate Matching: Does the rule require a “sister”? Do we have “sister” facts?

- Variable Matching: Can the specific people (objects) in our facts fit into the variables (A, B, C) of the rule without contradiction?

Figure 4 provides a clear visual of this logic check.

- Top Row (Predicate Matching): The rule requires

sister_ofandbrother_of. Fact F1 isgrandson_of, so it is discarded. Fact F2 issister_of, so it’s a match. - Bottom Row (Variable Matching): The rule requires a chain: \(A \to B \to C\). The system checks if the objects in the facts (Mary, John, James) can link together to form that chain. F4 (Clarence and Timmy) is discarded because they don’t connect to the existing chain.

This stage filters out the noise. The LLM is never distracted by irrelevant facts because the symbolic engine only feeds it the specific rule and facts that mathematically fit together.

3. LLM-based Rule Implementation (The “Neuro” Part)

Once the symbolic engine has identified Rule X and Facts Y and Z as the next logical step, it hands them over to the LLM.

Why use the LLM here? Why not just stay in code? Because real-world rules and facts are often nuanced. A purely symbolic solver might crash if there’s a slight mismatch in syntax. An LLM, however, is flexible.

The system prompts the LLM: “Given Rule X and Facts Y/Z, what is the new conclusion?” The LLM generates the new fact in both natural language and symbolic form. This new fact is written back into the Working Memory, and the cycle repeats.

Dynamic Schema Construction

A subtle but vital part of this process is how the memory schema is built. You cannot have “father” in one fact and “dad” in another—the symbolic engine won’t know they are the same.

Figure 6 shows how the system handles this. It performs a Schema Lookup before writing anything. If a concept already exists, it uses the existing symbol. If it’s new, it adds it. This ensures that the symbolic memory remains clean and connected, preventing the “fragmentation” that often confuses LLMs in long conversations.

Experimental Results

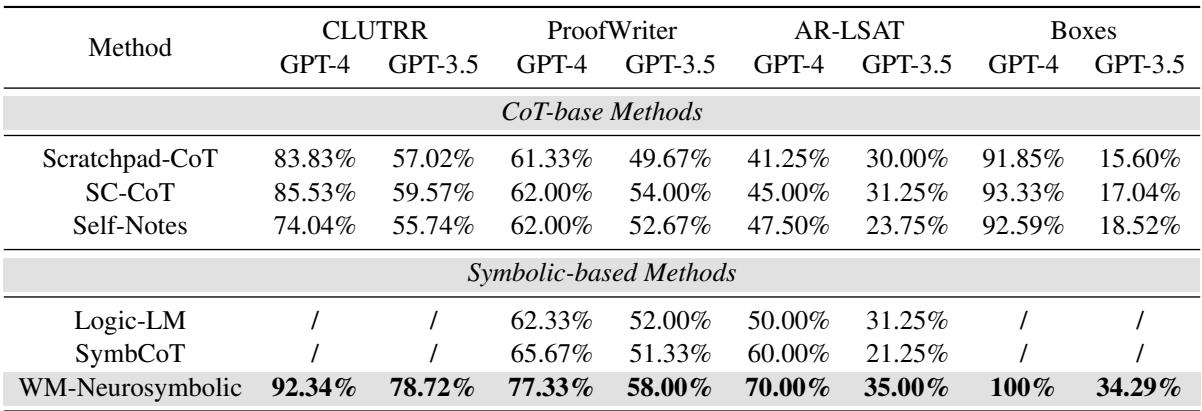

Does adding this “digital scratchpad” actually work? The researchers tested the framework against several baselines, including standard Scratchpad-CoT and other symbolic methods (like Logic-LM).

They used four datasets:

- CLUTRR: Kinship logic puzzles.

- ProofWriter: Abstract logic reasoning.

- AR-LSAT: Complex constraint satisfaction problems (from the Law School Admission Test).

- Boxes: Tracking objects moving between containers (state tracking).

Overall Performance

Table 1 presents the main results. The proposed method (WM-Neurosymbolic) is in the bottom row.

- Dominance: It significantly outperforms Chain-of-Thought (CoT) methods across the board.

- AR-LSAT: Look at the AR-LSAT column for GPT-4. Standard CoT achieves 41-45%. The Neurosymbolic method jumps to 70%. This is a massive improvement on a task known to be incredibly difficult for AI.

- Model Agnostic: The framework improves performance for both GPT-4 and the less powerful GPT-3.5, suggesting that the architecture helps weaker models “punch above their weight.”

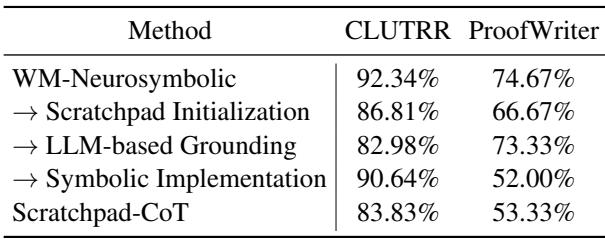

Why Does It Work? (Ablation Study)

To prove that every part of the engine is necessary, the researchers performed an ablation study (systematically removing parts of the framework to see what breaks).

Table 2 shows what happens when you strip features away:

- Scratchpad Initialization: If you use a simple scratchpad instead of the structured schema initialization, accuracy drops by ~6% on CLUTRR.

- LLM-based Grounding: This is the most telling result. If you replace the Symbolic grounding (the variable matching algorithm) with the LLM just “guessing” which rule applies, accuracy drops significantly (from 92% to 83% on CLUTRR). This confirms that LLMs are bad at finding the rule in the haystack.

- Symbolic Implementation: If you try to force the implementation to be purely symbolic (no LLM inference), performance also drops. The hybrid approach is best.

Robustness Over Long Reasoning Chains

Finally, the authors looked at how the model handles increasing complexity. As the number of reasoning steps increases, most models fall apart.

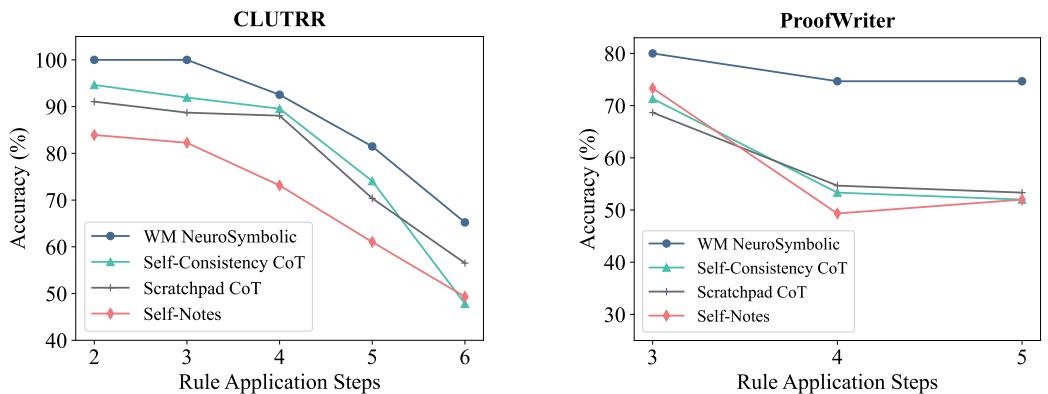

Figure 5 plots accuracy against the number of reasoning steps.

- Left Chart (CLUTRR): The blue line (WM Neurosymbolic) stays flat and high, near 90-100%, even as steps increase to 6. The other lines (standard prompting methods) dive downwards.

- Right Chart (ProofWriter): A similar trend. The framework is remarkably stable. Because the working memory offloads the cognitive load, the LLM doesn’t get “tired” or confused as the chain gets longer.

Why This Matters

This paper represents a crucial step in the evolution of AI reasoning. We are moving away from the idea that a single prompt, no matter how clever, can solve everything.

By treating the LLM not as the whole brain, but as the processing unit (CPU) connected to a structured memory (RAM) and a logic engine (ALU), we get the best of both worlds:

- Precision: The symbolic memory prevents the model from forgetting facts or applying rules to the wrong people.

- Flexibility: The LLM handles the messy translation of natural language into logic.

The “Neurosymbolic” future suggests that the path to true AI reasoning isn’t just making models bigger—it’s about giving them the right tools and architecture to organize their thoughts.

Key Takeaways

- LLMs struggle with Rule Grounding (finding the right rule) in multi-step reasoning, especially when data is unordered.

- Symbolic Working Memory stores facts in dual formats (Language + Logic) to allow precise tracking.

- The framework separates the process into Symbolic Matching (for precision) and LLM Implementation (for inference).

- This hybrid approach yields state-of-the-art results on complex logical reasoning benchmarks, significantly outperforming standard Chain-of-Thought prompting.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2408.13654/images/cover.png)