In human cognition, speaking and listening are not isolated islands. When we listen to someone, our brains actively predict what they are about to say. Conversely, when we speak, we often simulate how our words will be received by the listener to ensure clarity. This bidirectional relationship suggests that improving one skill should naturally help the other.

However, in the world of Artificial Intelligence, these two capabilities—generation (speaking) and comprehension (listening)—are often trained and treated as separate tasks.

In a fascinating paper titled “COGEN: Learning from Feedback with Coupled Comprehension and Generation,” researchers Mustafa Omer Gul and Yoav Artzi explore what happens when you tightly couple these two processes in an AI agent. They demonstrate that by linking comprehension and generation during both training and inference, an AI can learn significantly faster and communicate more naturally with humans.

This post will break down their method, the “virtuous cycle” of learning it creates, and the impressive results from their experiments with human users.

The Challenge: Learning from Interaction

The researchers situate their study in the context of continual learning. Unlike standard training, where a model consumes a massive static dataset and then stops learning, continual learning involves an agent that interacts with the world (or users), receives feedback, updates itself, and repeats the process.

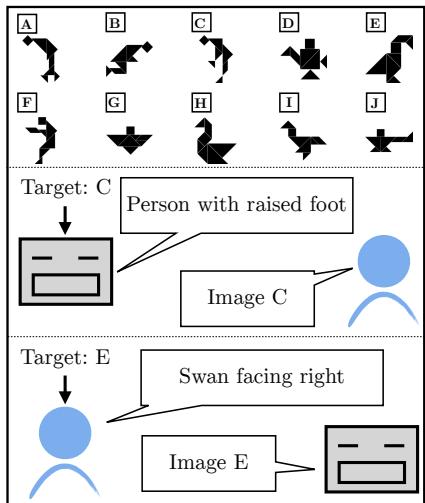

To test this, the authors used a Reference Game involving abstract visual stimuli called Tangrams.

As shown in Figure 1 above, the game involves two players:

- The Speaker: Sees a target image (e.g., Image C) and must describe it.

- The Listener: Sees a lineup of images and must identify the target based on the description.

This setup is deceptively difficult. The images are abstract shapes that don’t have standard names (unlike “cat” or “car”). Users have to be creative, describing them as “a person jumping” or “a swan facing right.” The AI model plays both roles, interacting with human partners. The goal is to see if the model can improve its communication skills over time purely based on binary feedback: Success (the partner guessed right) or Failure (they guessed wrong).

The Core Method: Coupling Comprehension and Generation

The standard approach to this problem would be to train two separate policies: one for guessing images (comprehension) and one for describing them (generation). The authors argue this is inefficient. Instead, they propose COGEN, a system that uses a single Large Language Model (LLM)—specifically IDEFICS2-8B—to handle both tasks, coupled through specific mechanisms.

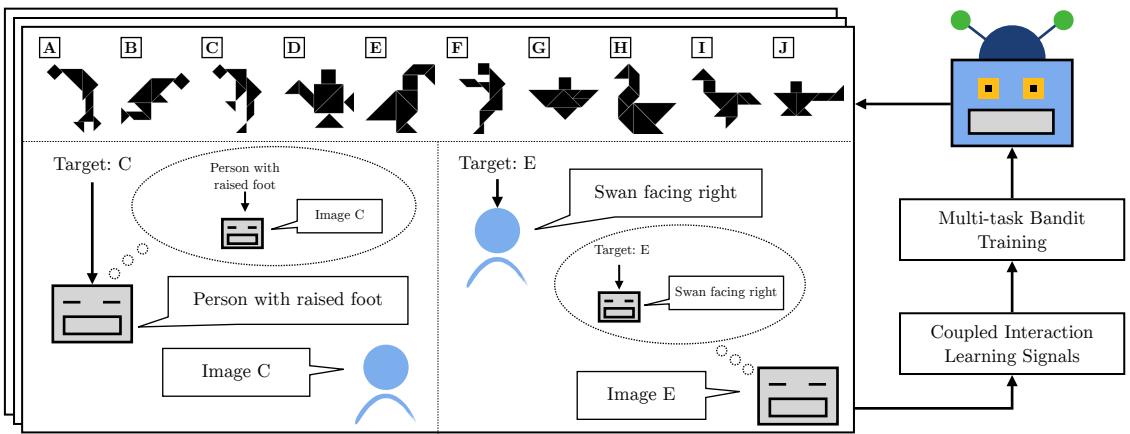

The overall workflow is a loop of interaction and training:

As Figure 2 illustrates, the model alternates between a deployment phase (playing games with humans) and a training phase. The innovation lies in how the “thought bubbles” (reasoning about the other role) and the feedback signals are used to couple the two skills.

The authors introduce two primary strategies for this coupling: Joint Inference and Data Sharing.

1. The Mathematical Foundation: Contextual Bandits

Before diving into the coupling, we need to understand how the model learns. Since the feedback is just “Success/Fail” rather than a corrected sentence, this is treated as a Contextual Bandit problem. The model optimizes its policy using the REINFORCE algorithm.

When the model receives a reward signal \(r\) (where \(r=1\) for success and \(r=-1\) for failure), it updates its parameters (\(\theta\)) using the following gradient update:

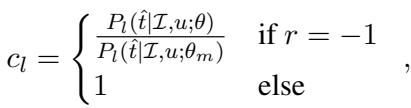

Here, \(\Delta_l\) represents the update for the comprehension (listener) task. A crucial component here is \(c_l\), a coefficient used to stabilize training. When a model fails (\(r=-1\)), simply pushing the probability down can be unstable if the probability is already low. The authors use an Inverse Propensity Score (IPS) clipping method:

This ensures that negative examples contribute to learning without destabilizing the model, a common issue in reinforcement learning with human feedback.

2. Strategy A: Data Sharing (Learning from the Partner)

The first major innovation is Data Sharing. In a standard setup, a generation model only learns from its own successful generations. If it says “weird bird” and wins, it reinforces “weird bird.”

But what if the AI is playing the Listener role? If the human partner says “dancing goose” and the AI correctly identifies the target, the AI has just received a high-quality data point: “dancing goose” is a valid description for this image.

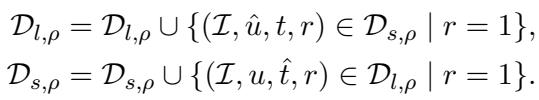

The authors formalized this by converting comprehension data into generation training data (and vice versa) whenever the interaction is successful (\(r=1\)).

In this equation:

- \(\mathcal{D}_{l, \rho}\) is the comprehension dataset at round \(\rho\).

- \(\mathcal{D}_{s, \rho}\) is the generation (speaker) dataset.

- The union operation (\(\cup\)) means effective examples from one task are added to the training set of the other.

Why this matters: This prevents the model from developing its own “alien language.” By constantly ingesting successful descriptions written by humans (during the listening phase) and using them to train its speaking ability, the model’s language remains grounded and human-like.

3. Strategy B: Joint Inference (Thinking Before Speaking)

The second strategy happens during the game, not just during training. It is based on the Rational Speech Act (RSA) framework.

When the AI acts as a Listener, it doesn’t just rely on its listener model (\(P_l\)). It also consults its internal speaker model (\(P_s\)). It asks, effectively: “If I were the speaker and wanted to describe image \(t\), how likely is it that I would have said utterance \(u\)?”

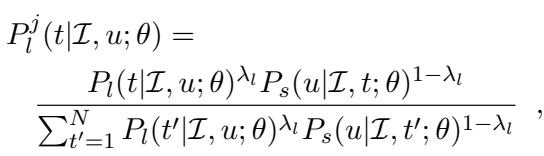

This equation shows the joint probability \(P_l^j\). It combines:

- Literal Listener probability (\(P_l\)): Does the description match the image?

- Speaker probability (\(P_s\)): Is this a description a speaker would actually use for this image?

This weighted combination (controlled by \(\lambda\)) allows the model to reason pragmatically, filtering out absurd interpretations or descriptions that technically match but are highly unlikely usage.

Experimental Results

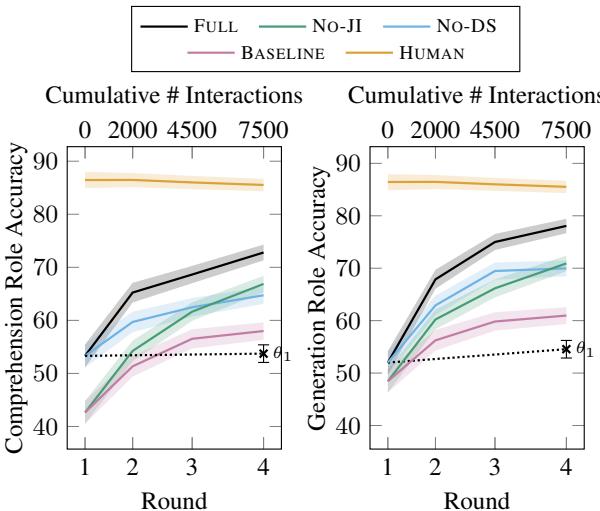

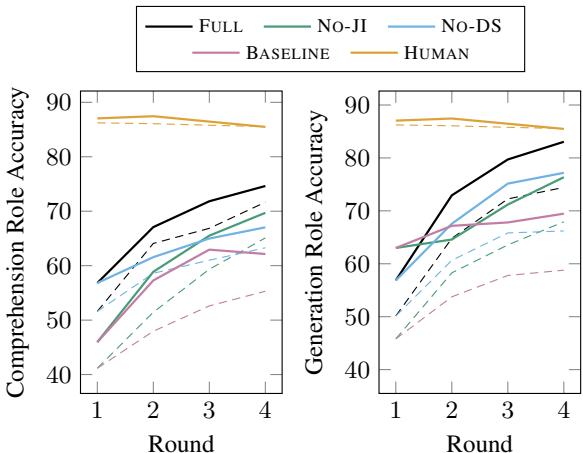

The researchers deployed this system on Amazon Mechanical Turk for four rounds of continual learning. They compared the FULL system (Joint Inference + Data Sharing) against ablated versions (No Joint Inference, No Data Sharing) and a BASELINE (neither).

Performance Gains

The results were stark. The coupled system significantly outperformed the baseline and the uncoupled variants.

In Figure 3, look at the Black Line (FULL) versus the Pink Dotted Line (BASELINE).

- Comprehension (Left): The FULL model improves steadily, ending nearly 15% higher than the baseline.

- Generation (Right): The gap is even wider. The FULL model achieves nearly 80% accuracy, while the baseline struggles to break 60%.

An interesting observation is that the No-JI (No Joint Inference) and No-DS (No Data Sharing) lines fall in the middle. This proves that both mechanisms contribute independently to the success.

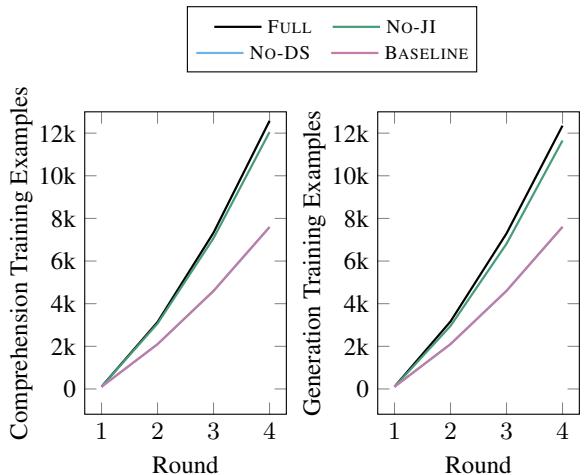

Data Efficiency

One of the most powerful benefits of Data Sharing is that it gives the model “free” data.

Figure 8 shows the volume of training examples. Because the FULL model (Black line) effectively swaps data between tasks, it accumulates training examples much faster than the baseline. This allows the model to learn more from fewer interactions—a critical factor when “interactions” cost real money and human time.

Language Quality

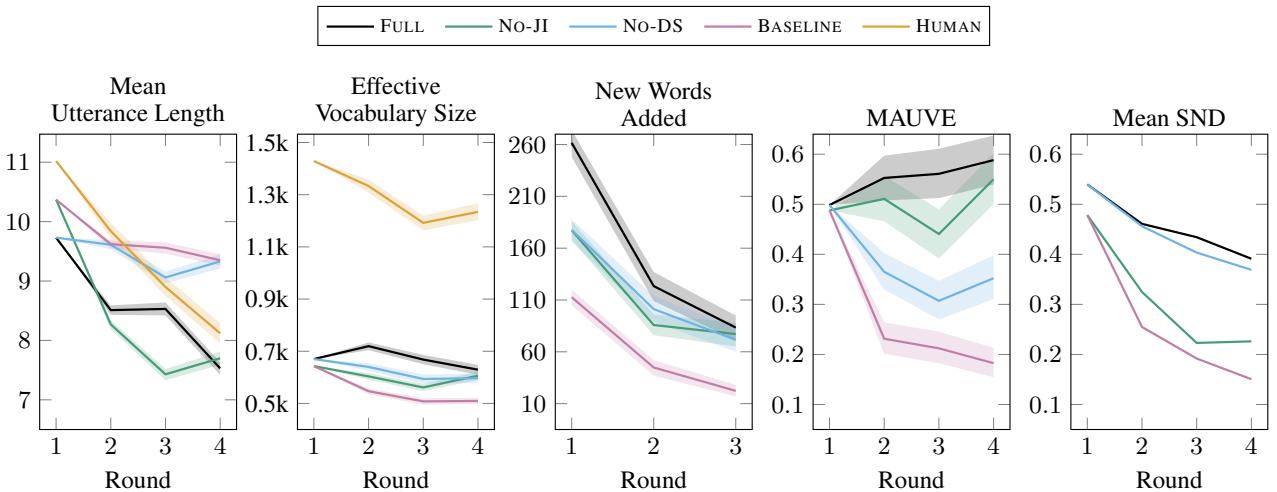

Did the model just get better at the game, or did it actually become a better communicator?

In closed-loop reinforcement learning, models often learn “gaming” strategies—using short, weird keywords that technically differentiate the images but don’t sound like human language. This is known as language drift.

The authors analyzed the language produced by the models:

Key takeaways from Figure 5:

- Utterance Length (Top Left): Humans (Orange) tend to use shorter descriptions as they become experts. The FULL model (Black) mimics this trend perfectly.

- Vocabulary (Top Center): The Baseline (Pink) collapses into a tiny vocabulary (repetitive speech). The FULL model maintains a much richer, larger vocabulary.

- MAUVE Score (Bottom Left): This metric measures how close the generated text is to human text (lower is better). The FULL model aligns closely with human distribution, while the baseline drifts far away.

The Spatial Reasoning Hurdle

Despite the success, the authors noted one persistent weakness: Spatial Reasoning.

When the target required spatial description (e.g., “The second one from the left”), performance dropped for all models (the solid lines in Figure 4). Vision-Language Models (VLMs) notoriously struggle with distinguishing “left” from “right” or “above” from “below” in complex compositions. While the coupled model still performed better than the baseline, the gap between AI and Human performance is most visible here.

Conclusion and Implications

The COGEN paper provides compelling evidence that coupling comprehension and generation creates a virtuous cycle for AI learning.

- Better Performance: By checking its own speech (Joint Inference), the model speaks more clearly.

- Faster Learning: By learning from its partner’s speech (Data Sharing), the model doubles its training signal.

- Human Alignment: By training on its partner’s language, the model resists the urge to invent its own weird dialect, staying grounded in natural language.

This work suggests that future AI agents—whether they are robots in our homes or chatbots on our screens—should not just be trained to talk or listen. They should be trained to do both, treating every interaction as an opportunity to refine both skills simultaneously. Just like humans, AI learns best when it engages in a two-way conversation.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2408.15992/images/cover.png)