Introduction: The Agony of the Untold Story

Maya Angelou once wrote, “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.” For millions of readers, this agony is compounded by a lack of representation. When you open a book, you are looking for a reflection—a character who looks like you, lives like you, and faces struggles you understand. These are called “mirror books.” They validate identity, foster belonging, and significantly improve reading engagement, especially in education.

However, the publishing industry has historically struggled to provide these mirrors for everyone. A massive gap exists between the diversity of the global population and the diversity of characters in literature.

But what if every reader could have a story written specifically for them?

In a fascinating new study titled “MIRRORSTORIES: Reflecting Diversity through Personalized Narrative Generation with Large Language Models,” researchers Yunusov, Sidat, and Emami explore whether Artificial Intelligence—specifically Large Language Models (LLMs)—can bridge this gap. They investigated whether AI can generate short stories that faithfully mirror a reader’s specific demographics and interests, and more importantly, whether readers actually prefer these stories over traditional human-written fables.

The Context: The Diversity Gap in Literature

Before diving into the AI solution, it is vital to understand the scale of the problem. Rudine Sims Bishop famously described books as “mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors.” Mirrors reflect our own lives; windows let us see others. When literature lacks diversity, minority groups are left without mirrors.

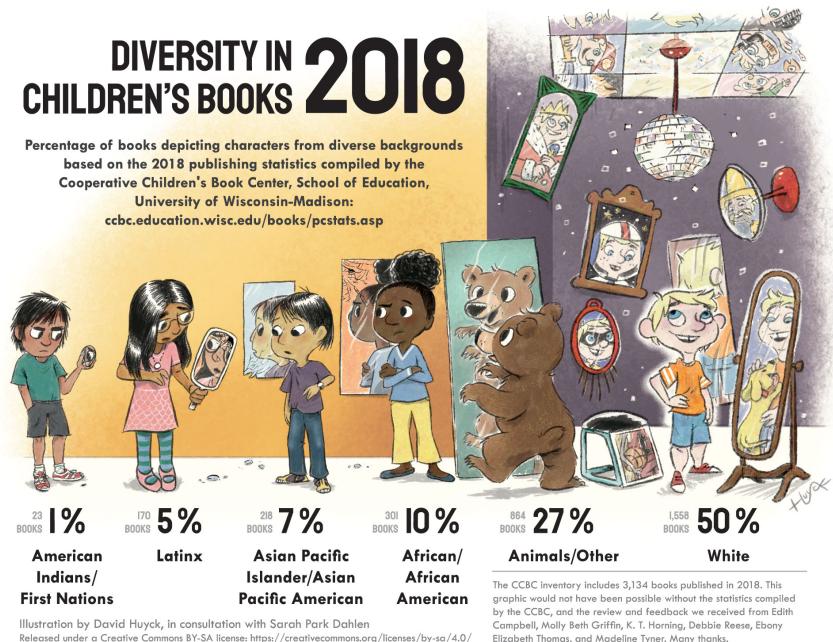

The researchers highlighted this disparity using data from the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC).

As shown in Figure 6, the statistics are stark. In 2018, a child was more likely to read a book about an animal or a truck (27%) than a book about an African American (10%), Asian (7%), Latinx (5%), or Indigenous (1%) character combined. White characters dominated the landscape at 50%.

While the publishing industry moves slowly to correct this, the authors of MIRRORSTORIES posit that LLMs (like GPT-4, Claude-3, and Gemini) offer a scalable, immediate solution to generate inclusive narratives on demand.

The Methodology: Building the MIRRORSTORIES Corpus

To test the efficacy of AI-generated personalized literature, the researchers didn’t just generate a few stories; they built a comprehensive corpus called MIRRORSTORIES. This dataset consists of 1,500 short stories designed to compare three distinct types of narrative generation.

The Three Contenders

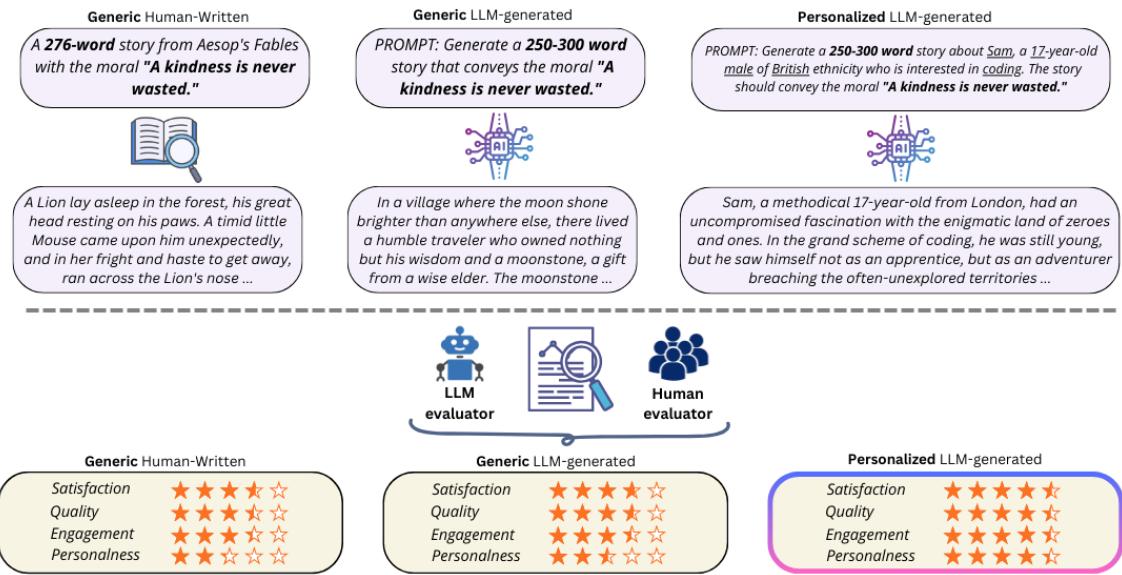

The study set up a “battle of the bards” between three categories of stories:

- Generic Human-Written: These were classic Aesop’s Fables. They are well-structured, moral-heavy, but generic in terms of character identity.

- Generic LLM-Generated: The AI was asked to write a story conveying a specific moral (e.g., “Kindness is never wasted”) without any specific personalization instructions.

- Personalized LLM-Generated: The AI was given a specific user profile (including name, age, gender, ethnicity, and interest) and asked to weave those elements into a story conveying the same moral.

Figure 1 illustrates this workflow. You can see how the prompt changes for the personalized version. Instead of a generic request, the model is fed specific “Identity Elements.” For example, the prompt might ask for a story about “Sam,” a “17-year-old British male” who likes “coding.”

The Identity Elements

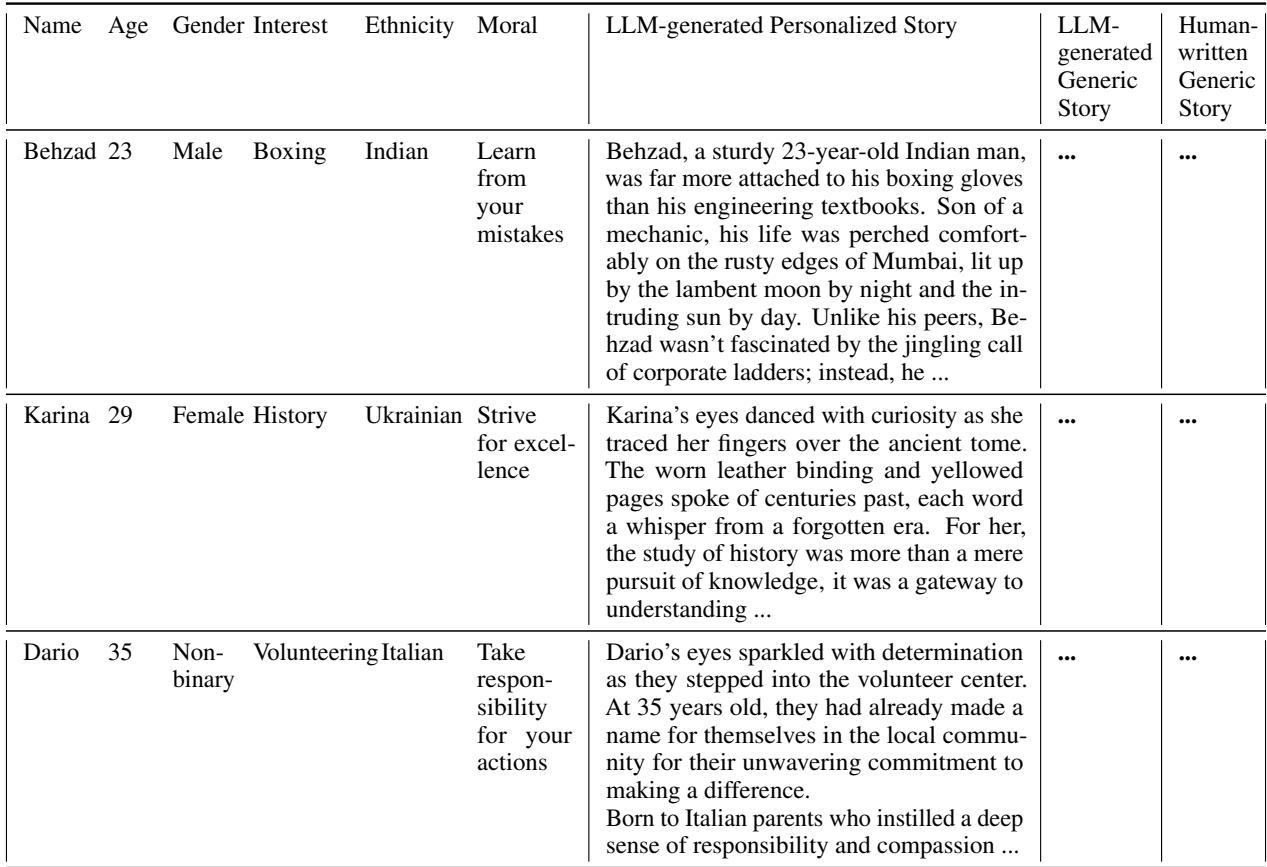

To ensure the personalized stories were truly diverse, the researchers didn’t rely on vague prompts. They structured their dataset around specific variables.

As detailed in Table 6 above, every entry in the dataset is anchored by a moral. The personalized stories then layer on specific attributes. The researchers drew from 123 unique ethnic backgrounds and 124 diverse interests, ranging from archery to coding.

This structured approach allowed them to systematically test if the AI could handle complex combinations—like a 29-year-old Ukrainian historian or a 35-year-old Italian volunteer—without losing the plot or the moral lesson.

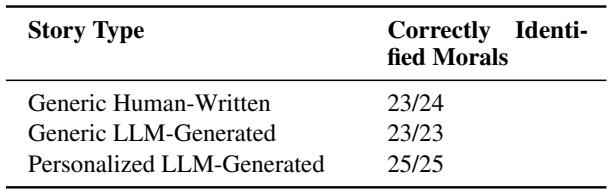

Validation: Did the AI Actually Listen?

Generating text is easy; generating accurate text that subtly incorporates personality traits is harder. Before testing user enjoyment, the researchers had to validate that the stories actually contained the requested elements.

They used both human evaluators and GPT-4 (acting as an evaluator) to read the stories and attempt to “guess” the demographics of the protagonist.

The results, shown in Figure 3, were impressive.

- Gender: Human evaluators identified the character’s gender with 100% accuracy.

- Ethnicity: Humans correctly identified ethnicity 94% of the time.

- Interests: The character’s specific hobby or interest was identified with 83% accuracy.

This confirms that current LLMs are highly capable of following complex instructions regarding character identity. They don’t just mention a name; they weave cultural markers and specific activities into the narrative texture effectively enough for readers to notice.

Visualizing the Personalization

To give you a sense of how the AI achieved this, the researchers used topic modeling (BERTopic) to analyze the most significant words in the generated stories.

Table 4 provides excellent examples of this “weaving” process.

- For Aveline, a non-binary French reader interested in reading, the story focuses on terms like library, truth, and joy.

- For Farida, an Uzbek carpenter, the top terms shift to craft, wood, and reputation.

The AI successfully shifted the vocabulary of the story to match the “world” of the reader.

The Results: Does Personalization Matter?

Now for the most critical question: Do readers actually like these stories better?

The researchers recruited a diverse group of human evaluators. They utilized a clever evaluation setup called “Personalization Impact.” Each evaluator received three stories:

- A generic Aesop fable.

- A generic AI story.

- A personalized AI story generated specifically for that evaluator based on their own demographics and interests.

They rated the stories on four metrics: Satisfaction, Quality, Engagement, and Personalness.

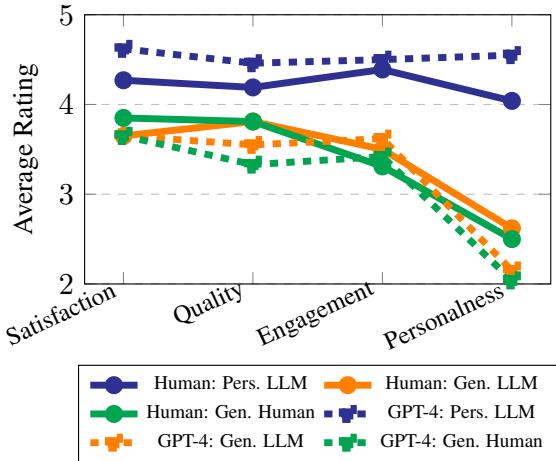

Figure 4 reveals the decisive victory for personalization.

- Generic AI vs. Human: Interestingly, generic AI stories (the purple dotted line) often scored lower or roughly equal to generic human stories. Simply using AI doesn’t guarantee a better story.

- The Personalization Boost: The personalized stories (the blue lines) scored significantly higher across the board.

- Engagement: Readers found stories about themselves much more captivating.

- Personalness: Naturally, this score skyrocketed.

- Quality & Satisfaction: Even the perceived quality of the writing was rated higher when the story was personalized.

The takeaway is clear: Personalization acts as a multiplier for engagement. Readers are willing to rate a story higher in quality simply because they feel seen by the narrative.

Bias in the Machine

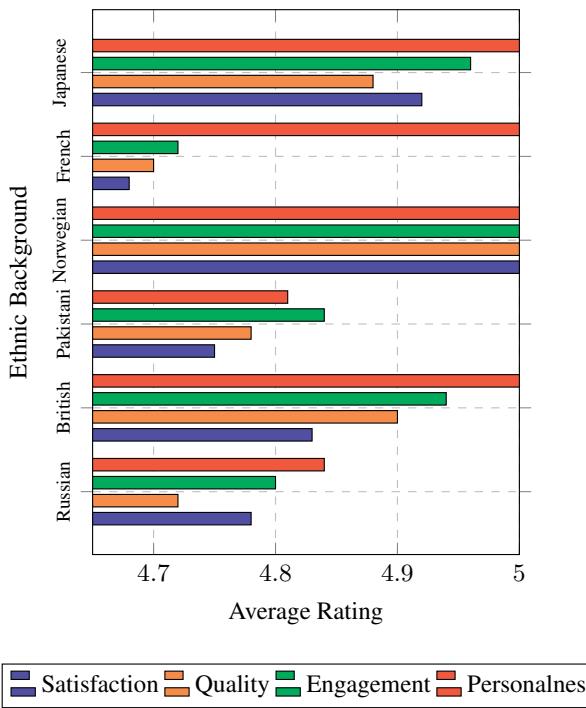

While the results were positive, the paper also serves as a cautionary tale about the inherent biases of LLMs. The researchers analyzed how GPT-4 evaluated these stories and found “preferential biases.”

Even when the quality of writing was similar, the AI evaluator tended to give higher scores to stories featuring certain demographics over others.

Figure 14 highlights a fascination within the model for specific cultures. Stories featuring Japanese and Norwegian characters consistently received higher ratings (pushing near 5.0) compared to stories featuring French or Pakistani characters.

Additionally, the researchers noted a gender bias. The model tended to rate stories with Non-binary characters higher in “Personalness” than those with Male or Female characters.

This is a crucial finding for developers. If we are to use AI to solve the diversity gap, we must ensure the AI itself doesn’t just replace one set of biases with another.

Beyond Text: Visualizing the Story

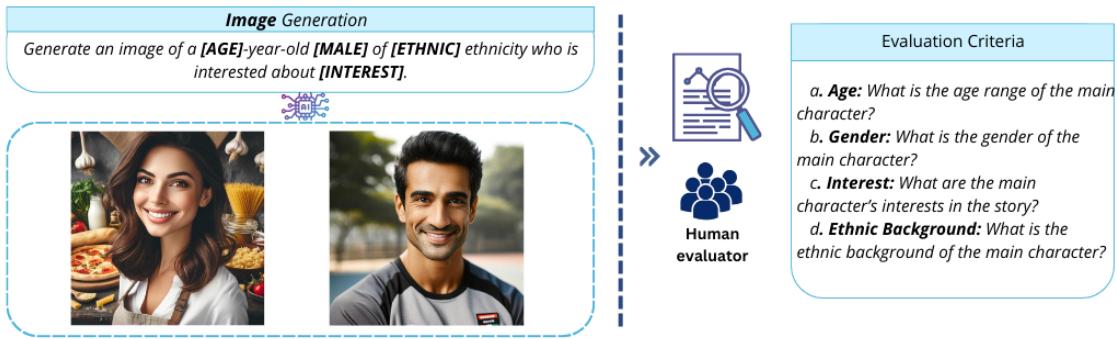

The “Mirror” experience is incomplete without illustrations. In a supplementary experiment, the researchers explored using image generation models (like DALL-E 2) to create personalized illustrations accompanying the text.

As shown in Figure 18, they used a similar prompt structure to generate images of the characters. Human evaluators were then asked to guess the age, gender, and ethnicity solely from the image.

The results were promising, particularly for Gender (100% accuracy) and Interests (95% accuracy). However, ethnicity was harder to visually represent accurately, with a lower identification rate (around 73%). This suggests that while text generation is highly mature for personalization, image generation still struggles with the nuances of specific ethnic representation without resorting to stereotypes.

Conclusion: The Future of Reading

The MIRRORSTORIES paper provides compelling evidence that we are entering a new era of literature. We are moving from a “one-to-many” model—where millions read the same book—to a potential “one-to-one” model, where narratives adapt to the reader.

The implications are profound, particularly for education. If a student is struggling with reading comprehension, a story tailored to their interest in “robotics” or “soccer,” featuring a protagonist who shares their background, could be the key to unlocking their potential.

However, the authors carefully note the limitations. These were short stories (approx. 300 words), and the evaluation was subjective. Furthermore, the preferential biases discovered in the models remind us that AI is not a neutral arbiter of culture.

Despite these challenges, MIRRORSTORIES demonstrates that AI can do more than just generate text; it can generate connection. By holding up a mirror to the reader, LLMs offer a way to make literature more inclusive, engaging, and personal than ever before.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2409.13935/images/cover.png)