Artificial Intelligence has made massive strides in seeing the world. Modern models can easily identify a cat in a photo or tell you that a car is red. This is known as visual perception. However, if you show an AI a picture of a person ironing a sandwich and ask, “Why is this funny?”, traditional models often fall apart. They might see the iron and the sandwich, but they fail to grasp the absurdity of the situation. This is the challenge of complex visual reasoning.

While Vision-Language Models (VLMs) like CLIP or BLIP are great at perception, and Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 or LLaMA are masters of reasoning, bridging the two without massive computational costs remains a hurdle. Typically, connecting vision to language requires training expensive “projection layers” on millions of image-text pairs.

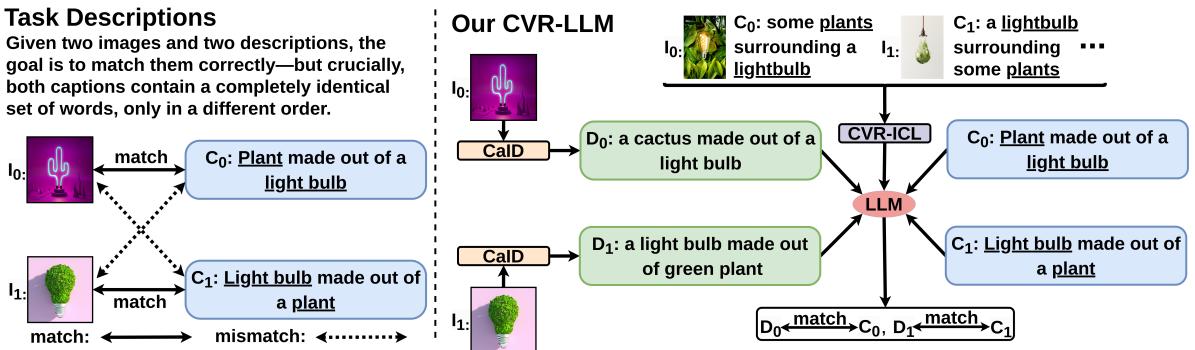

In this post, we are diving deep into a research paper from the University of Sydney that proposes a smarter, more efficient way to bridge this gap. They introduce CVR-LLM (Complex Visual Reasoning Large Language Models). Instead of retraining models to “see,” this approach translates visual information into rich, context-aware text descriptions that allow an LLM to reason about images using its existing text-based intelligence.

The Landscape of Visual Reasoning

Before dissecting the solution, we must understand the problem. Visual reasoning isn’t just about identifying objects; it’s about understanding relationships, cultural context, and common sense.

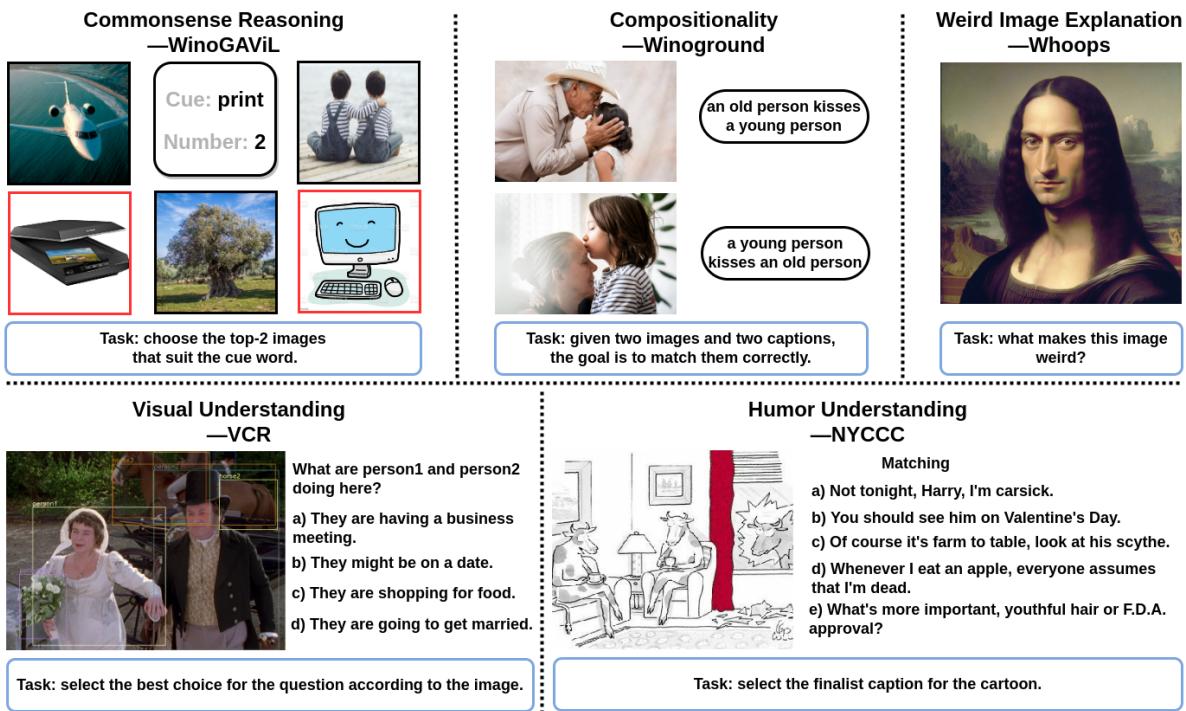

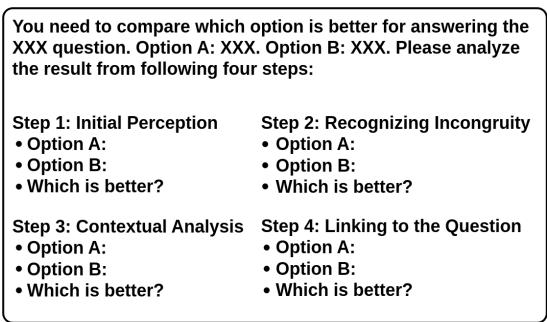

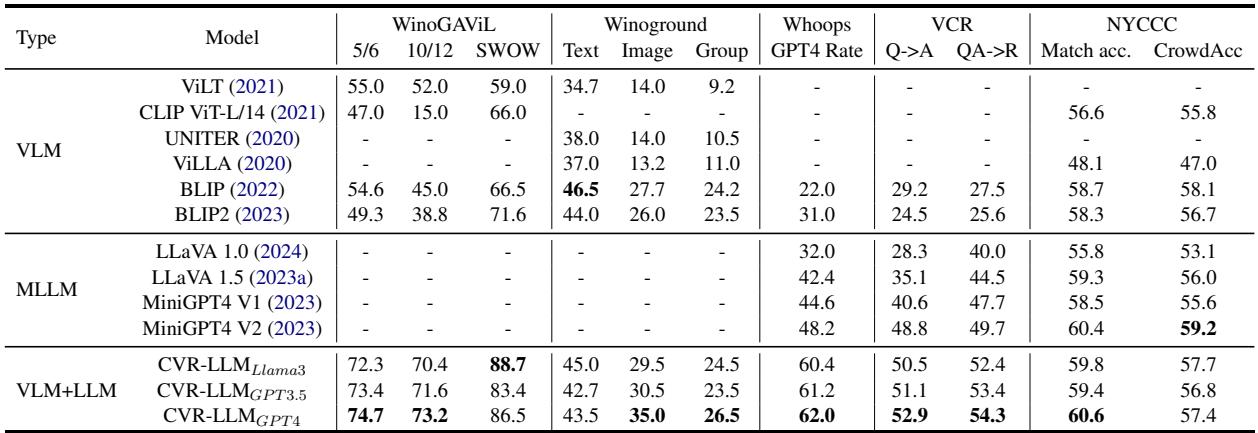

The researchers tested their model against five distinct, difficult benchmarks, as shown below:

- Commonsense Reasoning (WinoGAViL): Identifying images based on abstract associations (e.g., associating “print” with a scanner or a jet ski?).

- Compositionality (Winoground): Distinguishing between sentences where the word order changes the meaning entirely (e.g., “an old person kisses a young person” vs. “a young person kisses an old person”).

- Weird Image Explanation (Whoops): Explaining why an image is strange (e.g., the Mona Lisa with a male face).

- Visual Understanding (VCR): Inferring intent, such as why two people in suits are shaking hands.

- Humor Understanding (NYCCC): Matching a caption to a cartoon to make it funny.

Most Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) struggle here because they lack the specific “reasoning” layer to connect what they see with what they know about the world.

The Core Philosophy: VLM + LLM

The central thesis of CVR-LLM is simple yet profound: We don’t need to teach LLMs to see; we need to teach VLMs to describe things better.

Current state-of-the-art MLLMs (like LLaVA or MiniGPT-4) rely on a projection layer that translates visual features into a language format the LLM can digest. This works, but it is resource-intensive. CVR-LLM bypasses this by using an inference-only approach. It uses a “dual-loop” system where the LLM actually guides the vision model to look for specific details.

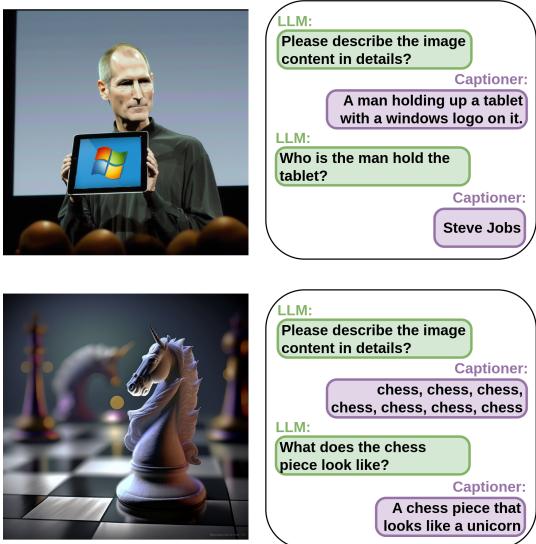

As illustrated above, rather than just feeding an image into a black box, the system generates a Context-Aware Image Description (CaID). For a task like Winoground, where the difference between a “plant made of a lightbulb” and a “lightbulb made of a plant” is subtle but crucial, a standard caption like “a lightbulb and a plant” would fail. CVR-LLM iteratively refines the description until it captures the specific semantic details needed to solve the puzzle.

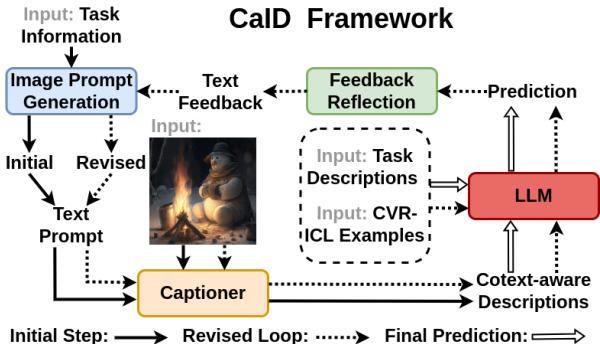

Method Part 1: Context-Aware Image Description (CaID)

The heart of this paper is the Context-Aware Image Description (CaID) framework. Standard image captioners are generic. If you show them a picture of a robbery, they might say “men in suits standing.” This is useless for answering “Why are these men dangerous?”

CaID solves this using a Self-Refinement Loop.

Here is how the process works step-by-step:

- Initial Captioning: The system generates a basic caption using a standard VLM (like BLIP-2).

- LLM Feedback: An LLM reviews this initial caption alongside the user’s question or task.

- The “Ask” Phase: The LLM realizes the initial caption is insufficient. It generates a specific query (e.g., “What are the men holding?”).

- Refined Captioning: The VLM re-scans the image, guided by this new query, and produces a richer, context-aware description (e.g., “The men in suits are holding guns”).

The Mathematical Formulation

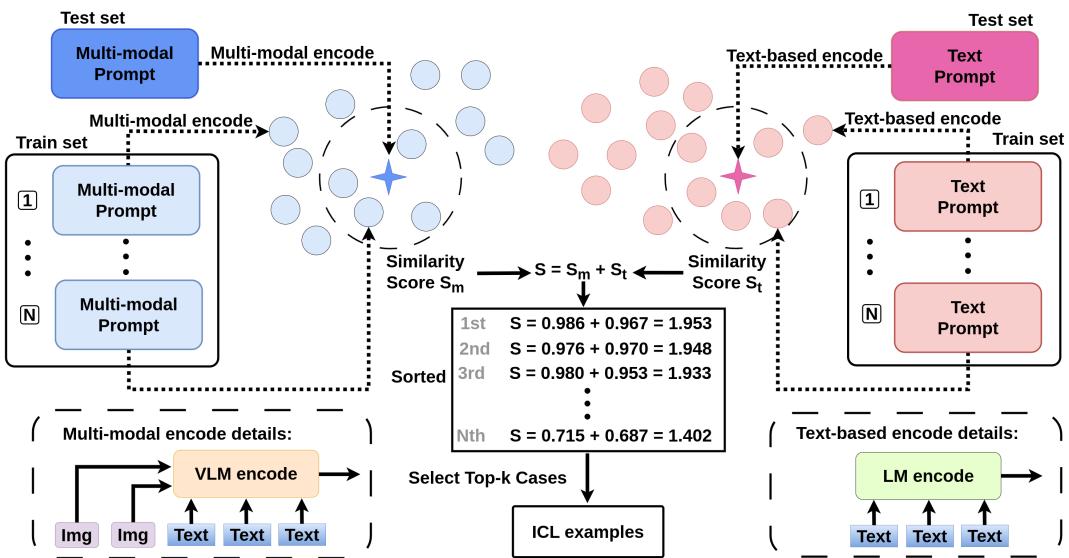

The researchers formalize this iterative process elegantly. The initial description (\(d_{init}\)) is generated by the captioner (\(C\)) using the image (\(i\)) and a prompt generated by the LLM (\(L\)) based on the task (\(t\)):

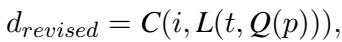

In the second loop, the system incorporates the LLM’s feedback. The LLM analyzes the initial prediction (\(p\)) and formulates a query (\(Q\)). This query is used to update the prompt, resulting in a revised description (\(d_{revised}\)):

This turns a generic “blind” guess into a targeted investigation.

A Concrete Example

To see this in action, look at the example below from the Visual Commonsense Reasoning (VCR) dataset. The question is “Why do Person1 and Person4 have guns?”

- Initial Caption: “An image of a man in a suit with a gun and another in a suit with a gun.”

- LLM Query: The LLM realizes it needs to differentiate them or understand their intent, so it asks, “What is the appearance of Person1 and Person4?”

- Refined Answer: The captioner updates the detail, noting specifically how they are dressed and interacting.

This specific detail allows the LLM to eventually conclude whether they are robbing a hotel or if they are security guards, based on visual cues that a generic caption would have missed.

Method Part 2: Complex Visual Reasoning In-Context Learning (CVR-ICL)

LLMs are famous for being “few-shot learners”—if you give them a few examples (context) of a task, they perform much better. This is called In-Context Learning (ICL).

However, selecting the right examples for a visual task is tricky. If you select examples based only on text similarity, you miss visual nuance. If you use only image similarity, you might miss semantic relevance.

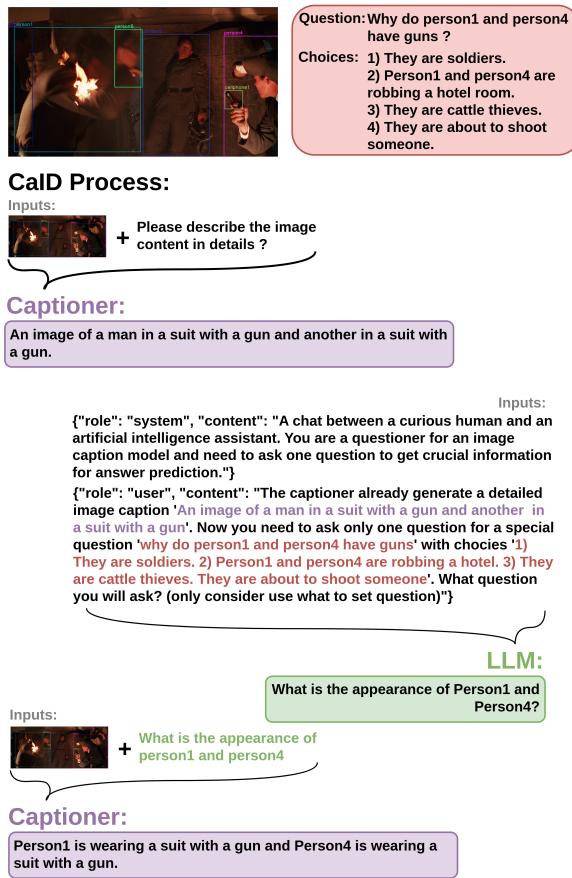

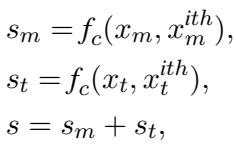

The authors propose CVR-ICL, a strategy that selects examples by analyzing similarity in both the text and visual domains.

How It Works

When the model receives a new test case:

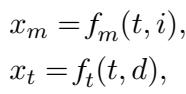

- Multi-Modal Encoding: It converts the image and text into a vector representation (\(x_m\)) using a VLM encoder (\(f_m\)).

- Text-Based Encoding: It converts the generated description and text into a vector (\(x_t\)) using a text encoder (\(f_t\)).

It then calculates similarity scores (\(s\)) between the current test case and potential examples in the training set by combining the cosine similarity (\(f_c\)) of both the multi-modal and text vectors.

The top-k examples with the highest combined score (\(s\)) are fed into the LLM as a prompt. This ensures that the examples the LLM sees are relevant not just in topic, but in visual composition.

The diagram below details this retrieval process on the WinoGAViL dataset, showing parallel pathways for visual and textual matching:

Evaluation: Measuring the Unmeasurable

How do you measure if an AI understands “weirdness”? Standard metrics like BLEU or CIDEr measure word overlap, but they are terrible at judging abstract reasoning.

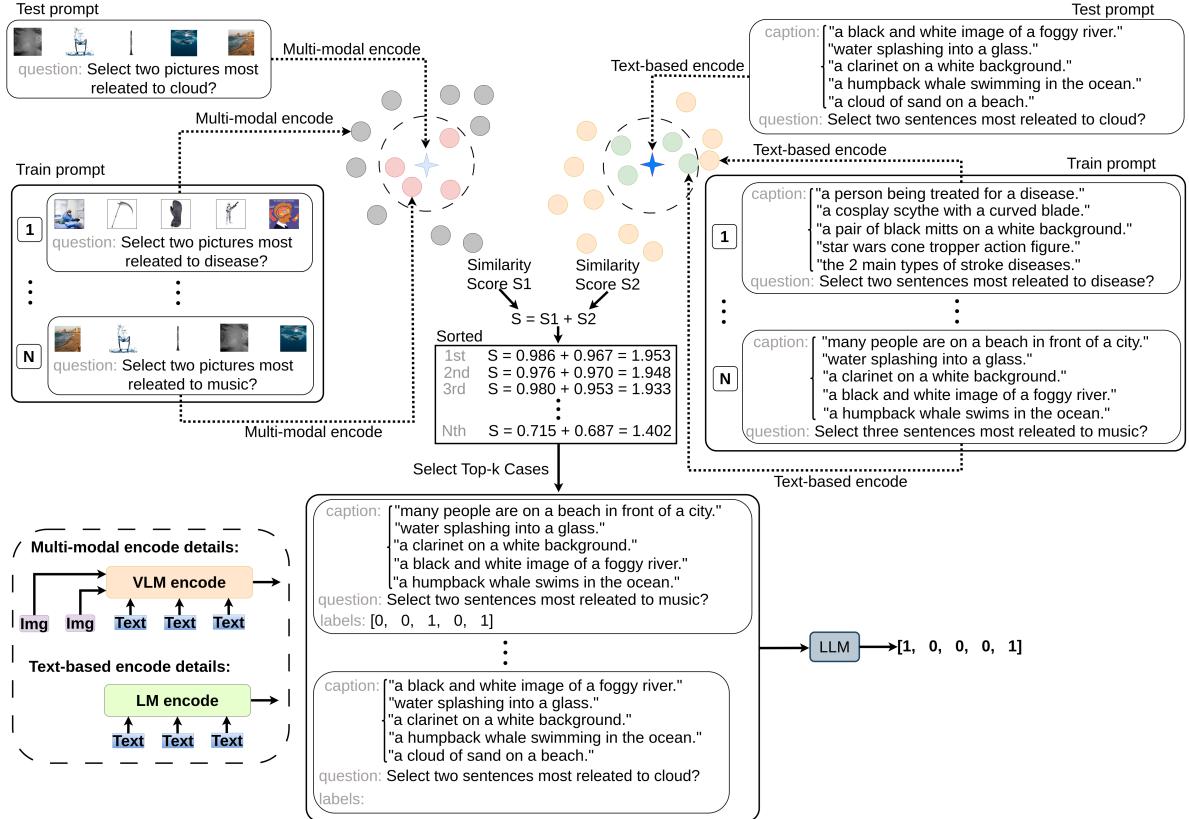

To address this, the authors introduce Chain-of-Comparison (CoC). This is a novel evaluation technique that uses GPT-4 as a judge. It forces the model to compare a generic caption (Option A) against the Context-Aware Description (Option B) through a four-step cognitive process:

- Initial Perception: What is the literal meaning?

- Recognizing Incongruity: Does it spot what is wrong or unusual?

- Contextual Analysis: How does it fit the scenario?

- Linking to the Question: Which option better answers the prompt?

The authors verified this hypothesis using GPT-4, finding that for complex tasks like “Whoops” (identifying weird images), the Context-Aware Descriptions were vastly superior to standard captions.

Experimental Results

So, does it work? The results suggest a resounding yes. CVR-LLM was tested against both traditional VLMs (like ViLT and CLIP) and modern MLLMs (like LLaVA and MiniGPT-4).

Key Findings:

- SOTA Performance: CVR-LLM achieved State-of-the-Art performance across all five benchmarks.

- Beating LLaVA: In the “Whoops” dataset (detecting weirdness), CVR-LLM (62.0 GPT-4 Rate) significantly outperformed LLaVA 1.5 (42.4).

- Versatility: It worked effectively regardless of whether the underlying LLM was LLaMA-3, GPT-3.5, or GPT-4.

Qualitative Analysis

The power of the model is best seen in qualitative examples. In the “Whoops” dataset example below, look at the chess piece (bottom row). A standard model might just see “chess pieces.” But the CVR-LLM asks, “What does the chess piece look like?” allowing it to identify that the piece looks like a unicorn, which explains why the image is “weird.”

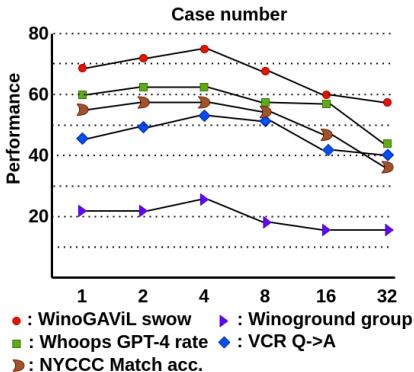

Sensitivity Analysis

The researchers also analyzed how many in-context examples (shots) were optimal. Interestingly, more isn’t always better. Performance peaked around 4 examples and then degraded or plateaued, likely due to the context window becoming cluttered or irrelevant.

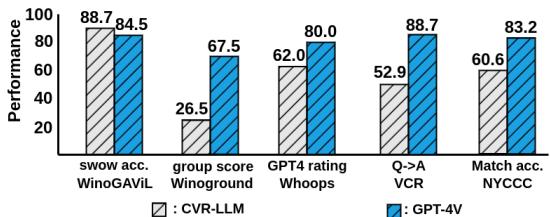

Comparison with GPT-4V

Perhaps the most ambitious comparison is against GPT-4V (GPT-4 with Vision), the current industry titan. GPT-4V is an end-to-end multimodal model, whereas CVR-LLM is a pipeline of separate models.

While GPT-4V generally outperforms CVR-LLM (which is expected given the resource difference), CVR-LLM actually surpassed GPT-4V on the WinoGAViL (SWOW) benchmark. This proves that a well-tuned pipeline of smaller models, using intelligent prompting and description refinement, can compete with massive end-to-end foundation models.

Conclusion

The “Enhancing Advanced Visual Reasoning Ability of Large Language Models” paper presents a compelling argument: we don’t always need bigger multi-modal models; we need smarter communication between the visual and textual modules we already have.

By implementing Context-Aware Image Descriptions (CaID), the authors turned the static process of image captioning into a dynamic conversation. By developing CVR-ICL, they ensured that the LLM is prompted with the most relevant multimodal examples.

This work democratizes complex visual reasoning. It shows that researchers and students don’t need massive compute clusters to train LLaVA-scale models to solve complex visual tasks. Instead, by leveraging the reasoning power of LLMs to guide the eyes of VLMs, we can achieve state-of-the-art results on some of the hardest problems in computer vision.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2409.13980/images/cover.png)