In the race to build Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), we often view Large Language Models (LLMs) as the ultimate replacements for traditional knowledge bases. We want to ask an AI, “Who was the president before Lincoln?” or “What album did Linkin Park release after Meteora?” and get an instant, accurate answer.

However, treating an LLM as a static encyclopedia reveals a critical flaw: Time.

Facts are not just isolated points of data; they are often sequences. Presidents serve terms in order. Software versions are released chronologically. If an LLM knows that Event B happened, it should logically understand that Event A happened before it and Event C happened after it. Furthermore, the model should give you the same answer whether you ask “What came after X?” or “X was followed by what?”

A recent research paper titled “Temporally Consistent Factuality Probing for Large Language Models” exposes a significant weakness in current state-of-the-art models: they are terrible at maintaining this “temporally consistent factuality.” In this deep dive, we will explore how the researchers diagnosed this problem with a new benchmark called TeCFaP, and how they proposed a novel solution called CoTSeLF to teach models to respect the timeline.

The Problem: Structural Simplicity vs. Temporal Reality

Before LLMs, we used Knowledge Bases (KBs)—structured databases containing facts like (Barack Obama, born_in, Hawaii). These systems are rigid but consistent. LLMs, on the other hand, are flexible. You can ask them questions in natural language.

But this flexibility comes at a cost. Existing benchmarks for LLMs typically check for “structural simplicity.” They ask if the model knows a subject, a relation, and an object (e.g., Paris is the capital of France). These facts are often treated as “contemporary,” meaning the subject and object exist simultaneously without a complex time dimension.

The researchers argue that this is insufficient. Information is generated, maintained, and lost over time. To truly trust an LLM, it must demonstrate Temporal Reasoning.

The Three Dimensions of Knowledge

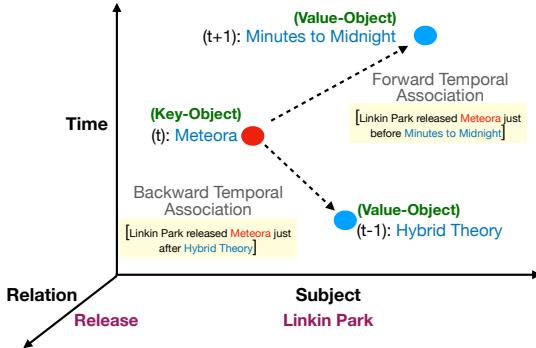

The authors visualize knowledge in a three-dimensional space:

- Subject: The entity we are talking about (e.g., Linkin Park).

- Relation: The action or connection (e.g., Released).

- Time: The specific point in history where this event occurred.

As shown in Figure 1, a true test of knowledge involves moving along the temporal axis. If the model knows the “Key Object” (e.g., the album Meteora at time \(t\)), can it correctly identify the “Value Object” at time \(t+1\) (the next album, Minutes to Midnight) or time \(t-1\) (the previous album, Hybrid Theory)?

Crucially, the model must be consistent. If the prompt implies a forward direction (“released just before…”) or a backward direction (“released just after…”), the model must navigate the timeline correctly.

Introducing TeCFaP and TEMP-COFAC

To test this capability, the researchers introduced TeCFaP (Temporally Consistent Factuality Probe). This is a task designed to check if an LLM can consistently retrieve facts based on their temporal order, regardless of how the question is phrased.

To run this task, they needed data. They couldn’t just use Wikipedia summaries; they needed strict, ordered sequences of events. They created a new dataset called TEMP-COFAC.

How TEMP-COFAC Was Built

The construction of this dataset was a rigorous, semi-automated process involving human experts to ensure high quality.

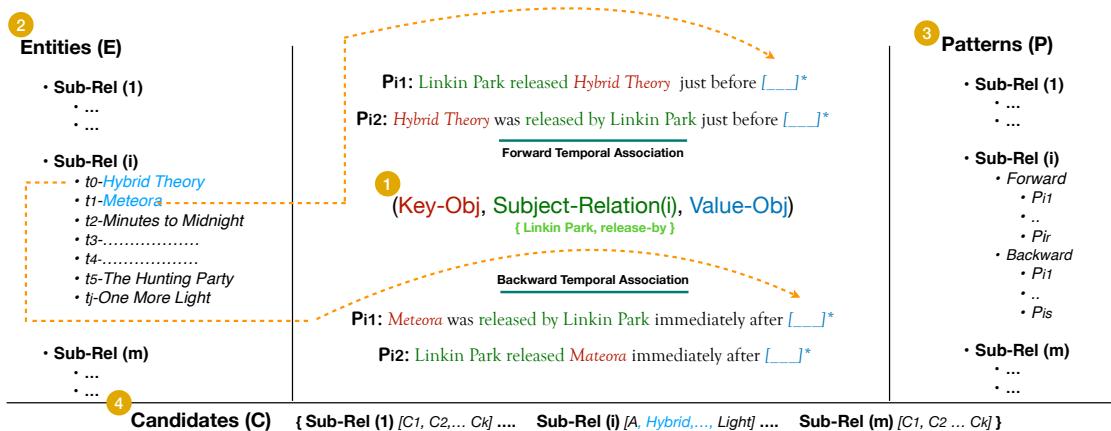

As illustrated in Figure 2, the process involves four distinct steps:

- Subject-Relation Pairs: They selected diverse topics like music, politics, technology, and corporate history (e.g., Linkin Park - released by).

- Entity Sequencing: They curated a list of entities strictly ordered by time (\(E_i\)). This isn’t just a bag of facts; it’s a timeline (e.g., \(t_0, t_1, t_2...\)).

- Paraphrasing Patterns: This is critical for testing consistency. They used tools and human verification to create multiple ways to ask the same temporal question.

- Forward: “X was released just before [Y]”

- Backward: “X was released immediately after [Y]”

- Candidate Sets: A vocabulary of possible answers to check if the model is hallucinating completely wild answers or just getting the sequence wrong.

The resulting dataset is robust, covering over 10,000 unique samples across centuries of history.

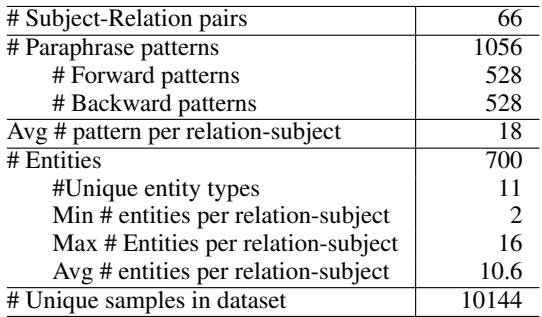

Table 1 shows the scale of the resource. With 66 distinct subject-relation pairs and over 1,000 paraphrase patterns, it provides a comprehensive stress test for any LLM.

The Metrics

The researchers defined three key metrics to score the models:

- Temporal Factuality (Temp-fact): Does the model give the correct answer? (e.g., If asked what came after Meteora, does it say Minutes to Midnight?)

- Temporal Consistency (Temp-cons): If we ask the question in 5 different ways (paraphrases), does the model give the identical answer every time? Note: The answer doesn’t have to be correct to be consistent, but a hallucinating model often gives different wrong answers to different prompts.

- Temporally Consistent Factuality (Temp-cons-fact): The gold standard. The model must be both correct and consistent across all paraphrases.

The Solution: CoTSeLF

When the researchers ran existing LLMs (like LLaMA and GPT-J) on this dataset, the results were abysmal (more on that in the Experiments section). To fix this, they proposed a new training framework: CoTSeLF (Consistent-Time-Sensitive Learning Framework).

CoTSeLF combines two powerful techniques: Multi-Task Instruction Tuning (MT-IT) and Consistent-Time-Sensitive Reinforcement Learning (CTSRL). Let’s break these down.

Phase 1: Multi-Task Instruction Tuning (MT-IT)

Standard instruction tuning teaches a model to follow a single command. The authors realized that to improve consistency, the model needs to understand that two different sentences can mean the same thing.

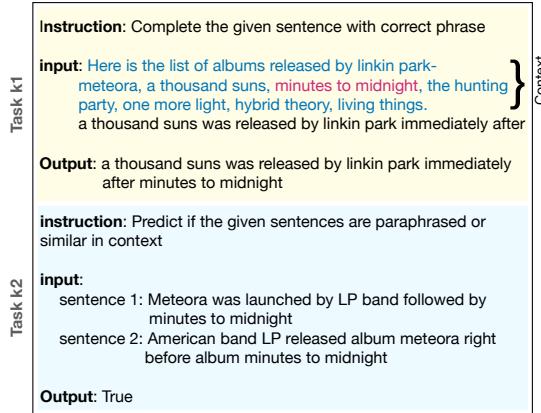

They set up a multi-task learning objective:

- Task k1 (Generation): The standard task. Given a context and a prompt, complete the sentence with the correct fact.

- Task k2 (Discrimination): A binary classification task. The model is shown two sentences and must decide: “Are these paraphrases of each other?”

Figure 3 shows this in action. By forcing the model to explicitly recognize paraphrases (Task k2) while learning to generate facts (Task k1), the model builds a more robust internal representation of the query’s intent, rather than getting distracted by the specific wording.

Phase 2: Consistent-Time-Sensitive Reinforcement Learning (CTSRL)

Instruction tuning gets the model part of the way there, but to truly align the model with temporal consistency, the researchers used Reinforcement Learning (RL).

In standard RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback), models are rewarded for producing “good” text. Here, the researchers designed a specific reward function that cares about Time and Consistency.

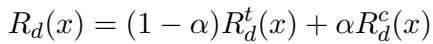

The reward function, \(R_d(x)\), is a weighted mix of two components:

Here is what the symbols mean:

- \(R_d^t(x)\): The Temporal reward. Did the model get the fact correct?

- \(R_d^c(x)\): The Consistency reward. Did the model recognize the paraphrase relationship correctly?

- \(\alpha\) (Alpha): A weighting parameter that balances how much the model should care about consistency versus pure accuracy.

The researchers specifically used a “Discrete” reward variant, where the model gets a score of 1 for being right and 0 for being wrong.

This formula effectively tells the model: “It is not enough to guess the right album. You must also understand that ‘released before’ and ‘preceded by’ imply the same temporal relationship.”

Experiments and Results

So, does CoTSeLF actually work? The researchers tested it against several baselines using the LLaMA family of models.

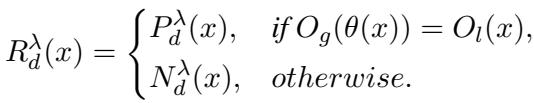

The Baseline: LLMs Struggle with Time

First, looking at the zero-shot performance (asking the model without any training examples), the results were shocking.

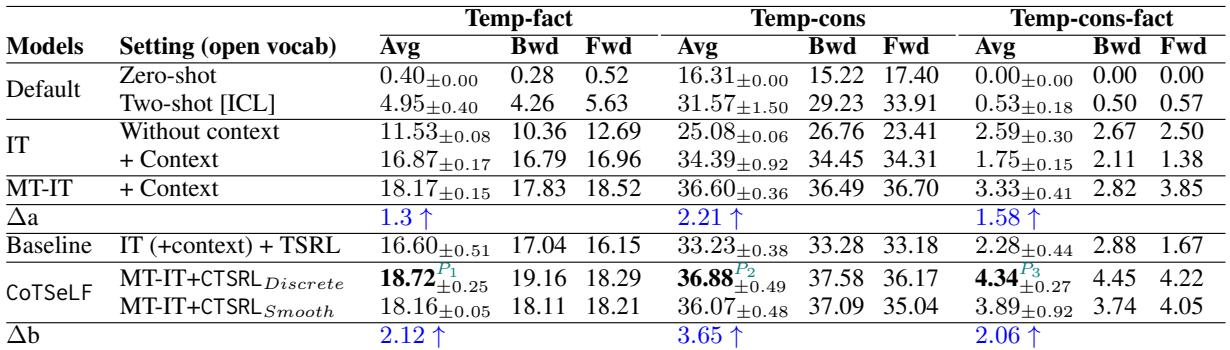

Table 2 reveals that standard models like LLaMA-7B and Falcon-7B have a Temporally Consistent Factuality (Temp-cons-fact) score of nearly 0%. Even the larger 13B models struggled to reach 1%. This confirms the hypothesis: standard pre-training does not equip models to handle strict temporal sequences consistently across paraphrases.

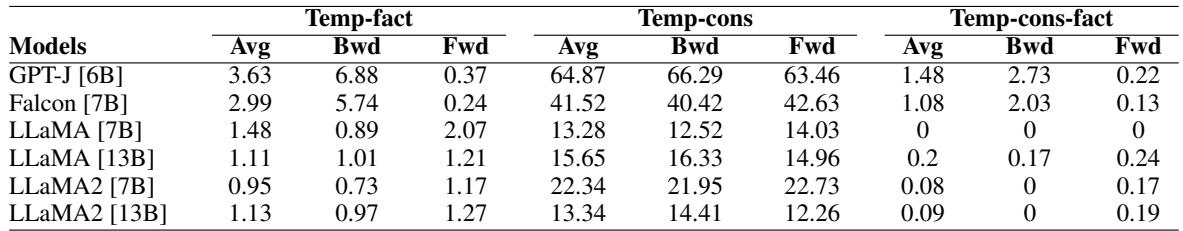

Knowledge vs. Time

An interesting side discovery was how the model’s knowledge varied depending on the historical era.

Figure 5 plots the model’s performance against history. Notice the massive spike on the right side of the graph (years 2011-2020). The model is much better at temporal reasoning for recent events than for events in the 1600s or 1700s. This bias likely stems from the training data—the internet (and Wikipedia) talks much more about recent pop culture and tech releases than historical sequences.

The CoTSeLF Improvement

When the researchers applied their CoTSeLF framework to the LLaMA-13B model, performance improved significantly.

Table 3 highlights the key results:

- Baseline (Zero-shot): Almost 0% consistent factuality.

- Baseline (Standard Instruction Tuning): ~1.75% consistent factuality.

- CoTSeLF (MT-IT + CTSRL): 4.34% consistent factuality.

While 4.34% might sound low in absolute terms, it represents a 90.4% improvement over the strongest baseline (TSRL) relative to the starting point. It also significantly boosted strict Temporal Factuality (accuracy) from 16.60% to 18.72%.

This proves that training for consistency doesn’t just make the model more stable; it actually helps it retrieve the correct information more often.

What is the model getting wrong?

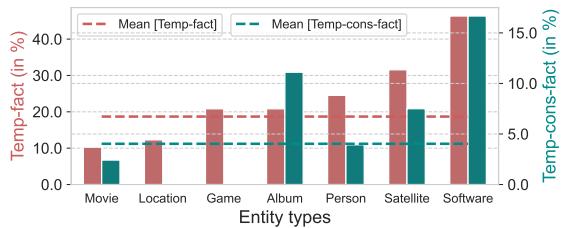

The researchers performed an error analysis to see which types of entities were hardest for the model.

Figure 8 shows that “Games,” “Satellites,” and “Software” had higher performance than “Movies” or “Locations.” This suggests that entity types with very strict, numbered versioning (like Android versions or sequential game sequels) might be easier for the model to latch onto than the more abstract release orders of movies or albums.

Why This Matters

This research highlights a critical gap in our current AI capabilities. If we want LLMs to function as reliable assistants for legal analysis (precedent A happened before precedent B), medical history (symptom X appeared after treatment Y), or historical education, they need to master time.

Key Takeaways:

- Paraphrasing Breaks Models: Changing the wording of a temporal question often causes current LLMs to hallucinate different answers.

- Strict Sequences are Hard: Models struggle with \(t-1\) and \(t+1\) logic, preferring to rely on loose associations rather than strict timelines.

- CoTSeLF Works: By explicitly training models to recognize paraphrases (Multi-Task Learning) and rewarding them for consistency (CTSRL), we can force them to structure their internal knowledge more effectively.

The TeCFaP benchmark sets a new standard for honesty in AI. It is not enough to know a fact once; an AI must know it consistently, regardless of how we ask or where that fact sits on the timeline of history.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2409.14065/images/cover.png)