Imagine you are cooking with a robot assistant. You ask it to “pass the large bowl.” The robot reaches for a colander. You immediately say, “No, the ceramic one on the left.” The robot pauses, processes your correction, and successfully hands you the mixing bowl.

This interaction seems trivial for humans. We constantly negotiate meaning in conversation. If we misunderstand something, we fix it and move on. However, for Artificial Intelligence—specifically Vision-Language Models (VLMs)—this process is incredibly difficult. Most current AI benchmarks focus on getting things right the first time based on a single instruction. But what happens when the AI gets it wrong? Can it recover?

In the paper “Repairs in a Block World: A New Benchmark for Handling User Corrections with Multi-Modal Language Models,” researchers from Heriot-Watt University explore this exact problem. They introduce a new dataset, establish human baselines, and propose novel training methods to help AI understand “Third Position Repairs”—the specific type of correction used when a misunderstanding becomes apparent.

This post will break down their research, explaining why robots struggle with corrections and how specific training techniques can make them better collaborators.

The Problem: Communication is a Two-Way Street

In the field of Natural Language Understanding (NLU), research often treats communication as a unilateral process: a human gives a command, and the machine executes it. But real conversation is active. It involves Communicative Grounding—the collaborative effort to ensure mutual understanding.

When miscommunication occurs, we use repair mechanisms. The authors focus specifically on Third Position Repairs (TPRs). Here is how a TPR sequence works:

- Turn 1 (Speaker): Sends a message (e.g., “Move the green block”).

- Turn 2 (Addressee): Responds or acts based on their understanding (e.g., The robot points to the wrong block).

- Turn 3 (Speaker): Realizes the misunderstanding and issues a repair (e.g., “No, the one below that”).

The ability to process this third turn is crucial for robust AI. If a model cannot handle a repair, the entire collaborative task fails.

Introducing BLOCKWORLD-REPAIRS

To study this, the researchers created BLOCKWORLD-REPAIRS (BW-R). This is a dataset of collaborative dialogues situated in a virtual tabletop manipulation task. The goal is simple: a human instructs a robot to pick up a specific block and move it to a specific location.

However, the task is designed to be ambiguous. The table is cluttered with similar-looking blocks, making single-turn instructions prone to failure.

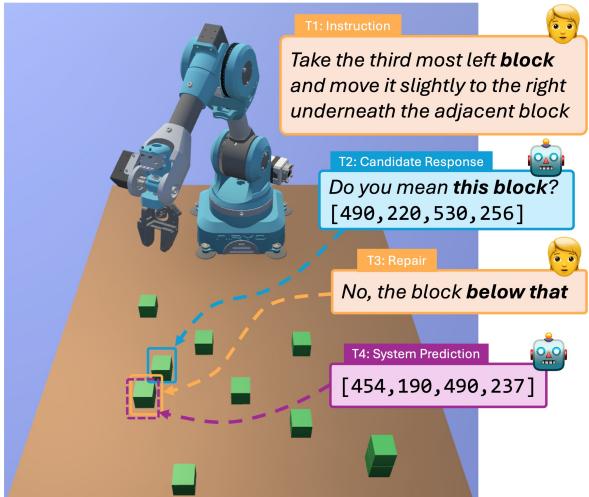

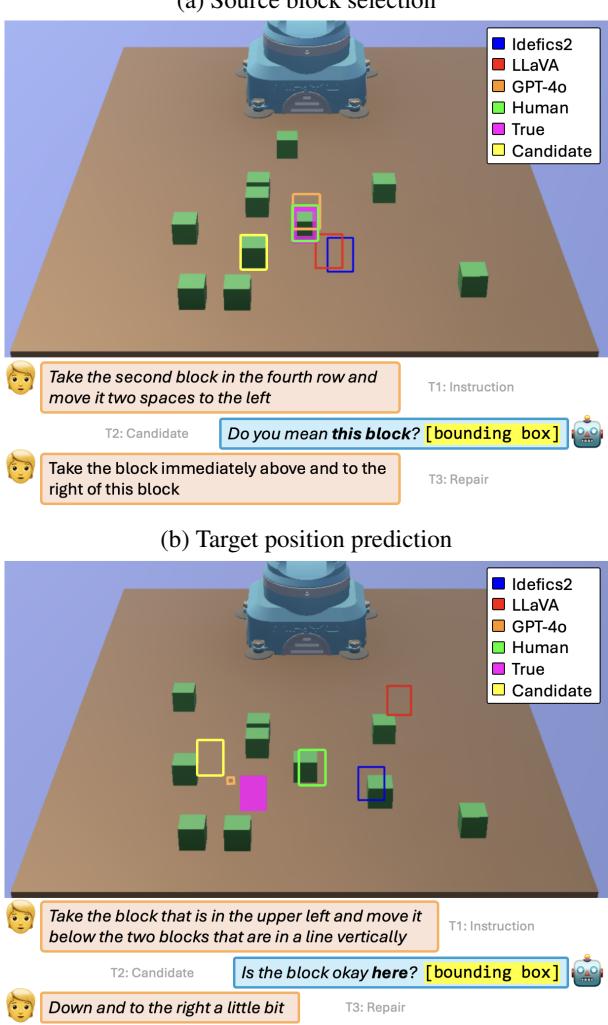

As shown in Figure 1, the dialogue follows a specific structure:

- T1 (Instruction): The user gives a complex command.

- T2 (Candidate Response): The system predicts a bounding box (often incorrect) and asks for confirmation.

- T3 (Repair): The user corrects the system, often using relative language like “the block below that.”

- T4 (System Prediction): The system must now combine the visual context, the original instruction, its own mistake, and the repair to find the correct target.

The dataset contains 795 dialogues collected via Amazon Mechanical Turk, focusing on complex multi-modal task instructions.

The Challenge for Current Models

Why is this hard for AI? Current Vision-Language Models (like LLaVA or Idefics2) are excellent at describing images or answering direct questions. However, they struggle with referential ambiguity and maintaining context over multiple turns.

The researchers tested several state-of-the-art models on this new dataset. They evaluated two distinct tasks:

- Source Block Selection: Identifying which block to pick up.

- Target Position Prediction: Identifying where to place the block (a coordinate on the table).

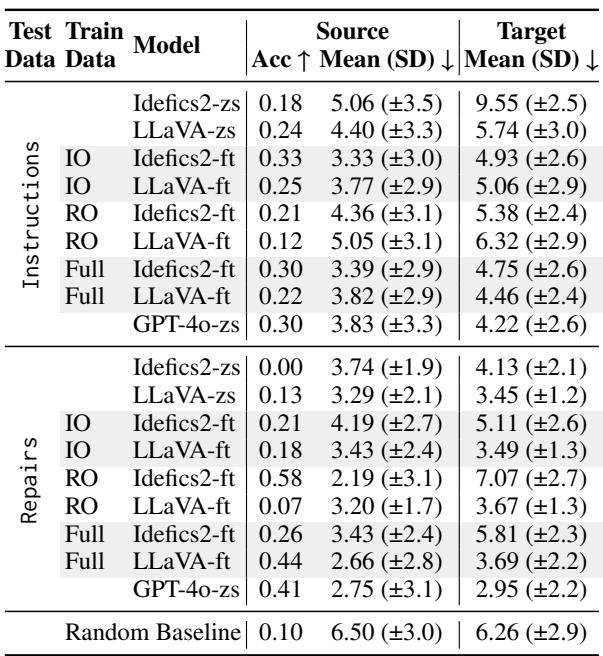

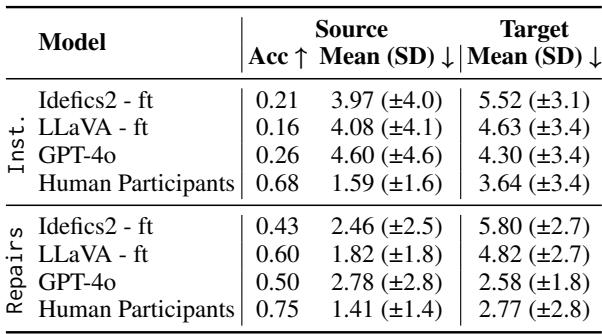

The results, shown in Table 1 below, reveal a significant gap.

In a Zero-Shot (zs) setting (where the model hasn’t been trained specifically on this task), the performance is poor. For example, Idefics2 has a 0.00 accuracy on repairs for source selection.

When the models are Fine-Tuned (ft), performance improves, but a fascinating issue emerges. Notice that models fine-tuned only on “Instructions” (IO) struggle with “Repairs” (RO), and vice versa. There is a cost to generalization. The models struggle to integrate the logic of a fresh instruction with the logic of a correction.

Core Method: Learning to Process Repairs

The researchers hypothesized that the standard way VLMs are trained might be part of the problem.

Typically, when a VLM is fine-tuned, it uses a Cross-Entropy Loss calculated on all the tokens it generates. In the context of a dialogue containing a mistake, this is problematic. If the training data includes the robot’s incorrect guess (Turn 2) followed by the user’s correction, the model might be “learning” from its own hallucinated or incorrect intermediate tokens.

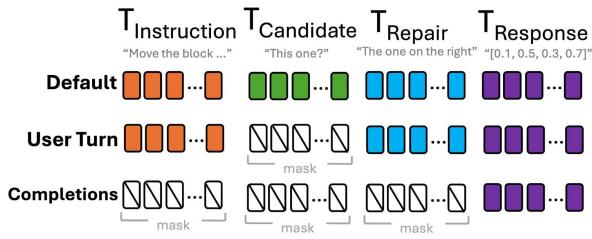

To fix this, the authors experimented with Token Masking Strategies. They modified the loss function to ignore specific parts of the dialogue during training.

Figure 2 illustrates the three strategies tested:

- Default Loss: The model calculates loss on all system outputs, including the incorrect candidate response (T2) and the final correct response (T4).

- Risk: The model learns from the “bad” tokens in the middle.

- User-Turn Loss: The loss is calculated for the user’s instructions and the final correct response. The intermediate system turn is masked.

- Completion-Only Loss: The model only calculates loss on the final, correct bounding box prediction (T4). It effectively treats the entire dialogue history (Instruction + Mistake + Repair) as a prompt and is only penalized based on the final answer.

The Results of Masking

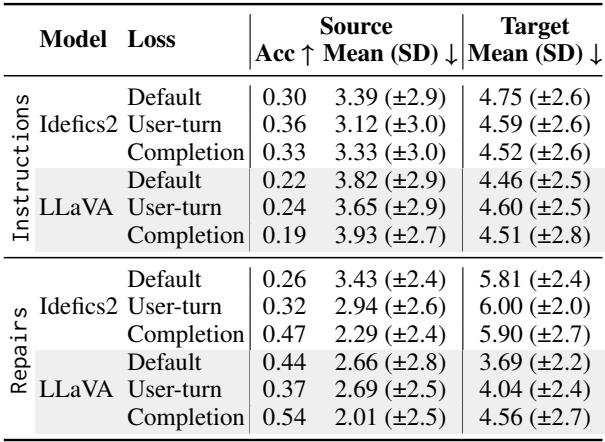

Did masking the “bad” intermediate tokens help? The results in Table 2 suggest that it did, particularly for generalization.

The Completion-Only loss (bottom rows for each model) showed the strongest results when training on the full dataset.

- For LLaVA, accuracy on repairs jumped to 0.54 (compared to 0.44 with default loss).

- For Idefics2, accuracy on repairs hit 0.47 (compared to 0.26 with default loss).

This indicates that by preventing the model from optimizing on its own simulated mistakes, we encourage it to view the dialogue history as context for the final, correct solution. It learns to “listen” to the repair rather than reinforcing the error.

Human vs. Machine: The Performance Gap

To understand how far AI has left to go, the researchers conducted an in-person study where humans played the role of the robot. They were shown the same dialogues and images and asked to select the blocks.

Table 3 highlights the stark reality.

Humans achieved 75% accuracy on repairs for source selection, whereas the best fine-tuned model (LLaVA) reached 60%, and GPT-4o only reached 50%.

The gap is even wider for Target Position Prediction (determining where to drop the block). This is a much harder task because it involves identifying an empty space relative to other objects (e.g., “to the right of the stack”). Humans maintained low error distances (2.77), while models struggled significantly.

Visualizing the Errors

We can see these struggles in action in Figure 3.

In the top image (a), the models (Blue and Red boxes) fail to identify the correct block despite the repair. The human participant (Green box) correctly identifies the target. The models struggle with abstract concepts like “rows” or “columns” and often latch onto simpler keywords like “left” or “right” without understanding the full relational context.

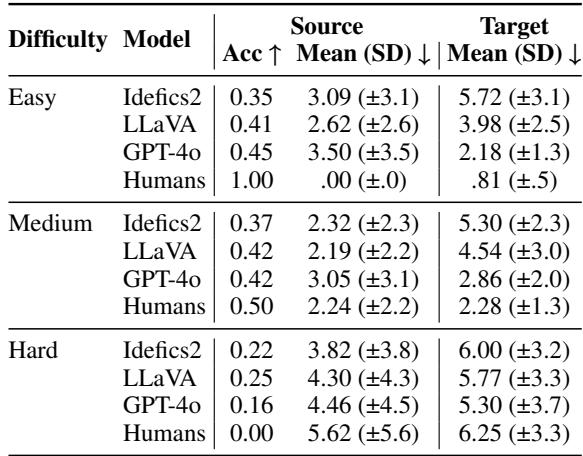

The Paradox of Difficulty

One of the most surprising findings came from analyzing the “difficulty” of the tasks. The researchers categorized the dialogues into Easy, Medium, and Hard based on human performance. You would expect AI to follow the same trend: doing well on easy tasks and failing on hard ones.

Table 4 reveals the opposite.

Look at the Hard category for Source Block selection. Humans have 0.00 accuracy (by definition of the category), yet LLaVA achieves 0.25 and Idefics2 achieves 0.22. Conversely, on Easy tasks where humans are perfect (1.00), the models perform poorly (0.35 - 0.45).

Why does this happen? The researchers suggest a linguistic reason. “Easy” examples for humans often involve long, descriptive sentences (more words). “Hard” examples might be short and underspecified (fewer words). VLMs, which rely heavily on text patterns, might actually find the “hard” (short) instructions easier to parse, even if they are ambiguous to humans. Conversely, complex, verbose descriptions that are clear to humans might overwhelm the model’s spatial reasoning capabilities.

Conclusion and Implications

The BLOCKWORLD-REPAIRS benchmark demonstrates that while Vision-Language Models are advancing, they are not yet ready for seamless collaboration in the physical world.

- Repairs are distinctive: They require a model to revise its internal understanding based on new information, not just process a fresh command.

- Training matters: Standard training objectives can be detrimental when data involves mistakes. Masking out intermediate errors helps models generalize better.

- The “Human” gap: Models struggle with spatial relations and abstract concepts (like “the third row”) that humans find intuitive.

For students and researchers, this paper highlights a critical area for future work: Learning from Interaction. To build truly helpful robots, we cannot just train them on static instructions. We must train them to listen, make mistakes, and most importantly, understand us when we say, “No, not that one.”

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2409.14247/images/cover.png)