Introduction

In the digital age, memes are more than just funny pictures; they are a sophisticated language of their own. They can distill complex political opinions, social commentary, and cultural inside jokes into a single, shareable unit. However, this power has a dark side. Memes have become a potent vehicle for hate speech, cyberbullying, and disinformation, often hiding behind layers of irony and sarcasm that traditional content moderation systems struggle to parse.

The core of the problem lies in the multimodal nature of memes. An image of a smiling cartoon character might be harmless on its own, and the text “Be proud of yourself” is positive in isolation. But combine a specific image with specific text, and the meaning can shift from support to mockery, or even to hate speech. This complexity is particularly acute for marginalized communities, such as the LGBTQ+ community, where the line between an empowering statement, a humorous in-joke, and a hateful slur can be incredibly thin.

In this deep dive, we explore a recent research paper that tackles this challenge head-on. The researchers introduce PrideMM, a nuanced dataset focused on LGBTQ+ imagery, and MemeCLIP, a novel framework designed to understand the subtleties of memes efficiently. By leveraging the power of large-scale pre-training and adapting it with lightweight architecture, this work represents a significant step forward in making the internet a safer, more inclusive space.

The Context: Why Meme Analysis is Hard

To understand why this research is necessary, we first need to look at the limitations of previous approaches.

The Gap in Existing Datasets

Most existing datasets for hate speech detection are binary: they label an image as either “Hate” or “Not Hate.” While this is a good starting point, it fails to capture the spectrum of human expression. A meme might be offensive to some but not hateful, or it might be intended as satire (humor) rather than an attack.

Furthermore, general datasets often lack the specific context required to understand hate directed at specific groups. The researchers identified a significant gap in resources regarding the LGBTQ+ movement. Previous attempts to moderate content in this domain often resulted in the suppression of all LGBTQ+ content due to a lack of nuance—an outcome known as “sanitized censorship.”

Introducing PrideMM

To address this, the authors released PrideMM, a dataset of 5,063 text-embedded images collected from Twitter, Facebook, and Reddit. What makes PrideMM unique is its multi-aspect annotation schema. Instead of a simple binary label, every image is analyzed across four distinct tasks:

- Hate Speech Detection: Is the content hateful?

- Hate Target Classification: If it is hateful, who is the target? (Undirected, Individual, Community, or Organization).

- Stance Classification: Does the meme support, oppose, or remain neutral toward the LGBTQ+ movement?

- Humor Detection: Is the meme intended to be funny?

As shown in Figure 1 above, the dataset captures the complexity of these interactions. For example, image (c) might be classified as “No Hate” regarding speech, but “Oppose” regarding stance, while image (b) targets specific individuals (J.K. Rowling). This granularity allows models to learn the difference between a joke, a political stance, and actual hate speech.

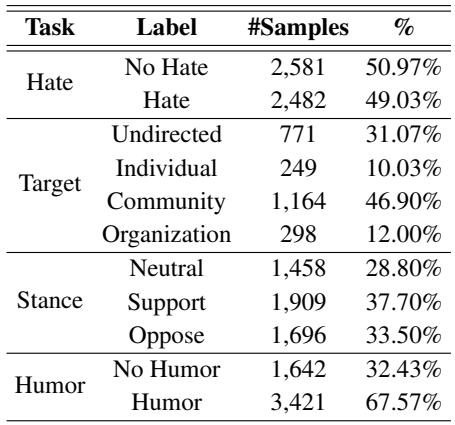

Table 2 highlights the distribution of the dataset. While the “Hate” label is fairly balanced, tasks like “Target” classification are heavily imbalanced, with most hate directed at the “Community” rather than specific individuals. This imbalance presents a classic machine learning challenge that the authors’ proposed model, MemeCLIP, aims to solve.

The Core Method: MemeCLIP

The heart of this research is MemeCLIP, a framework designed to classify these complex multimodal inputs effectively.

The researchers built their solution on top of CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-Training). CLIP is a massive foundation model trained on 400 million image-text pairs. It excels at understanding the general relationship between visual concepts and language. However, using CLIP directly for meme classification has pitfalls:

- Overfitting: Fine-tuning a massive model like CLIP on a small dataset (like PrideMM) often destroys its general knowledge (catastrophic forgetting).

- Entanglement: CLIP is trained to match images with descriptive text (e.g., a photo of a dog with the text “a dog”). Memes, however, often rely on mismatch or irony, where the text and image contradict each other to create meaning.

MemeCLIP solves these issues using a lightweight, modular architecture.

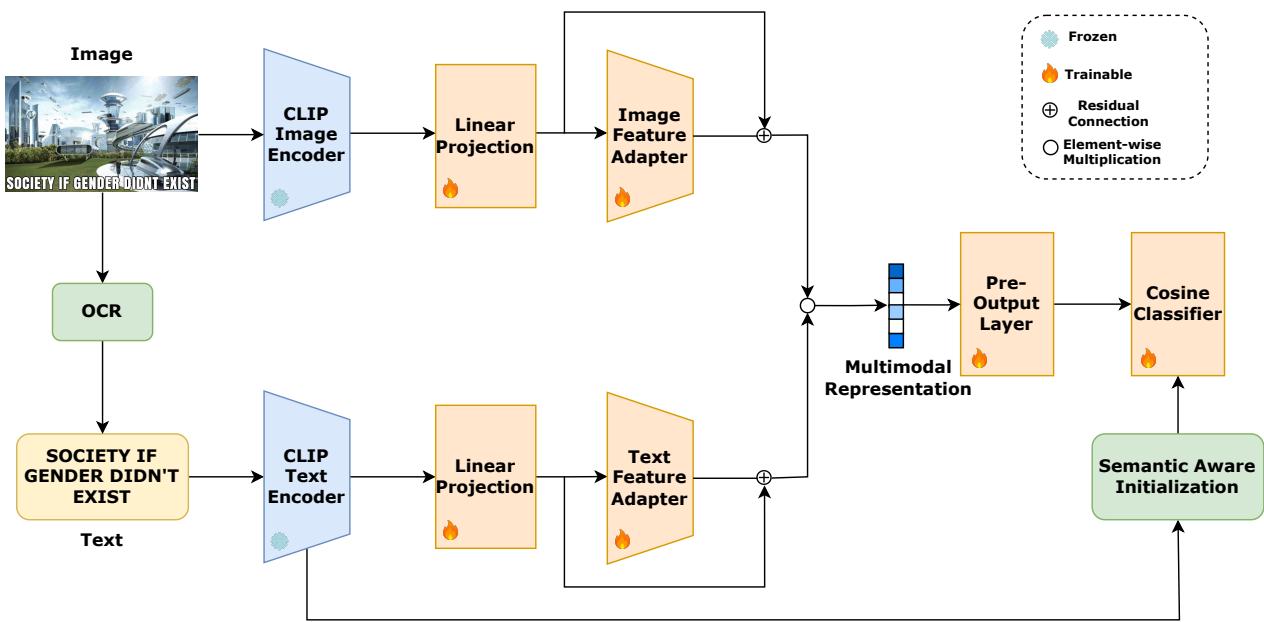

Let’s break down the architecture shown in Figure 2 step-by-step.

1. Frozen Encoders

The process begins with the standard CLIP Image (\(E_I\)) and Text (\(E_T\)) encoders. Crucially, the authors freeze these weights. This ensures that the rich, general knowledge CLIP learned from the internet is preserved and not overwritten during training.

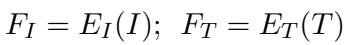

Here, \(F_I\) and \(F_T\) represent the raw feature embeddings extracted from the image and text, respectively.

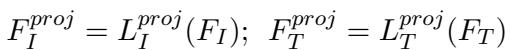

2. Linear Projection Layers

Because memes often use text and images in contrasting ways (unlike the standard captioning data CLIP was trained on), the raw embeddings might be too tightly aligned. The researchers introduce linear projection layers to “disentangle” the modalities within the embedding space.

This step maps the features into a space where the model can better analyze the specific interplay between the meme’s text and visual components.

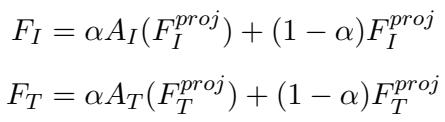

3. Feature Adapters with Residual Connections

This is the most innovative part of the framework. Instead of fine-tuning the whole model, MemeCLIP uses Feature Adapters. These are lightweight, trainable modules inserted after the projection layers.

To get the best of both worlds—the general knowledge of frozen CLIP and the specific knowledge of meme culture—the framework uses a residual connection.

In these equations, \(\alpha\) is a “residual ratio” (set to 0.2 in experiments). This parameter balances the input: it takes a small amount of information from the new, learned Adapter (\(A_I\)) and combines it with a larger portion of the original, projected features. This technique, heavily inspired by recent advancements in parameter-efficient fine-tuning, prevents overfitting while allowing the model to adapt to the specific nuances of the dataset.

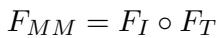

4. Modality Fusion

Once the image and text features are adapted, they need to be combined. The authors chose a simple yet effective method: element-wise multiplication.

This results in a single vector, \(F_{MM}\), that encapsulates the combined semantic meaning of the meme.

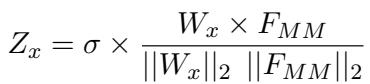

5. The Cosine Classifier and Semantic-Aware Initialization

Finally, the fused representation must be classified. Standard linear classifiers can be biased toward majority classes (a major issue in the “Target” task of PrideMM). To mitigate this, MemeCLIP uses a Cosine Classifier.

By normalizing the weights (\(W_x\)) and the features (\(F_{MM}\)), the prediction depends on the angle between vectors rather than their magnitude. This makes the model more robust to class imbalance.

Furthermore, the classifier weights are not initialized randomly. The authors employ Semantic-Aware Initialization (SAI). They use the text encoder to generate embeddings for the class labels themselves (e.g., “A photo of Hate Speech”) and use those embeddings to initialize the classifier. This gives the model a “head start” by injecting semantic understanding of the labels before training even begins.

Experiments and Results

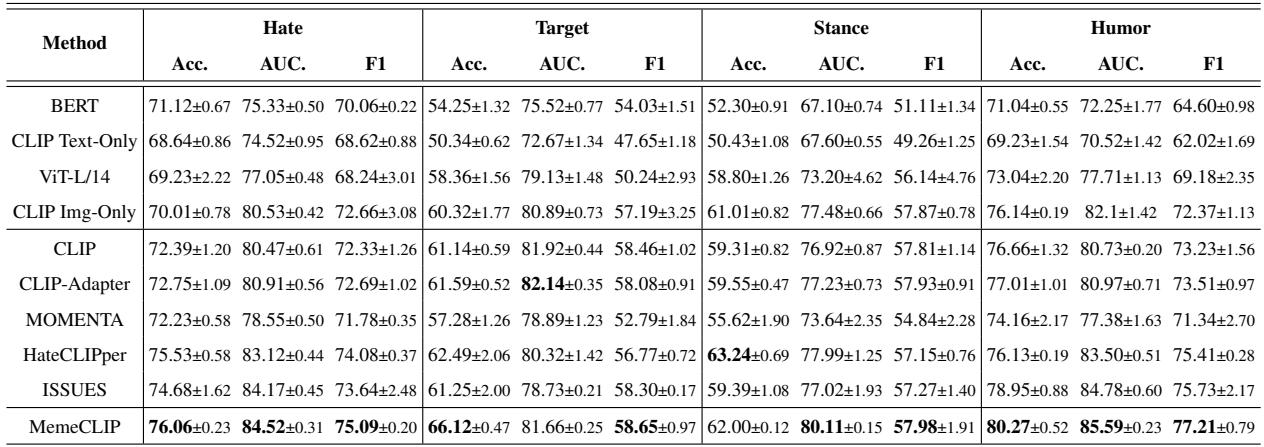

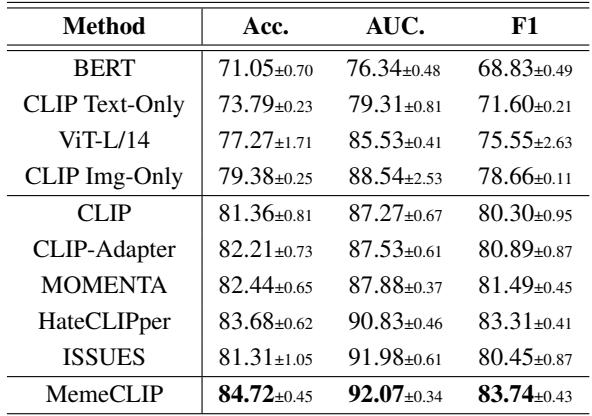

The researchers compared MemeCLIP against several baselines, including unimodal models (text-only BERT, image-only ViT) and other multimodal frameworks like MOMENTA and HateCLIPper.

Performance on PrideMM

The results on the new PrideMM dataset were compelling.

As shown in Table 3, MemeCLIP achieved the best performance across almost all metrics for Hate, Target, and Humor classification.

- Target Classification: Note the significant jump in performance (F1-score) for the “Target” task compared to other methods. This validates the effectiveness of the Cosine Classifier in handling imbalanced classes.

- Unimodal vs. Multimodal: The table also confirms that text-only or image-only models generally perform worse, proving that understanding memes requires looking at both modalities simultaneously.

Generalization to HarMeme

To prove that MemeCLIP isn’t just good at LGBTQ+ memes, the authors tested it on HarMeme, a dataset related to COVID-19 hate speech.

Table 4 shows that MemeCLIP generalizes well, outperforming state-of-the-art baselines like HateCLIPper and ISSUES. This suggests the architecture is robust across different topics of hate speech.

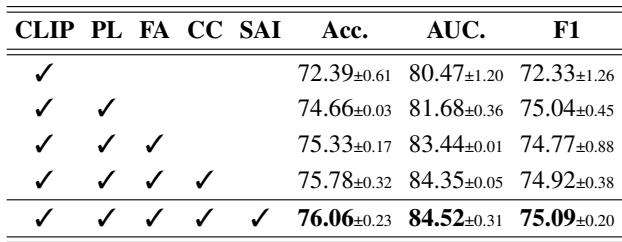

Ablation Study: Do we need all the parts?

A common question in machine learning is whether every component is necessary. The authors conducted an ablation study to find out.

Table 5 demonstrates a clear progression.

- Row 1: Using just CLIP with projection layers gives a baseline accuracy of 72.39%.

- Row 2: Adding Feature Adapters boosts this significantly to 74.66%.

- Row 3 & 4: Adding the Cosine Classifier and Semantic-Aware Initialization provides the final push to 76.06%. Every component contributes to the final success of the model.

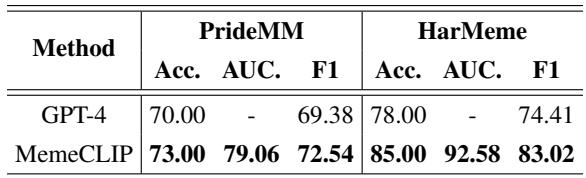

MemeCLIP vs. GPT-4

In an era dominated by Large Language Models, how does a specialized model compare to a giant like GPT-4? The researchers ran a zero-shot comparison using GPT-4.

Table 6 reveals an interesting finding: MemeCLIP outperforms GPT-4. Qualitative analysis suggested that GPT-4 is often “too safe.” Due to its safety alignment (RLHF), GPT-4 tends to over-censor, classifying non-hateful but controversial images as hate speech. MemeCLIP, being fine-tuned on the specific domain, understands the nuances better and makes fewer false positives.

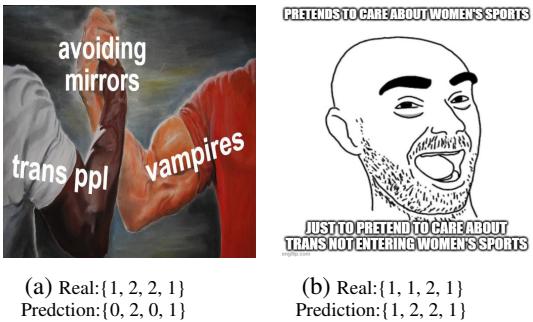

Where Does It Fail?

No model is perfect. The authors provide a look at misclassified samples to understand the remaining challenges.

Figure 3 shows the difficulty of the task.

- Example (a): A meme depicting arms of “trans ppl” and “vampires” joining together. MemeCLIP predicted “No Hate” (0), but the ground truth was “Hate” (1). The model likely missed the subtle derogatory association implied by the text “avoiding mirrors,” interpreting the “handshake meme” template as inherently positive.

- Example (b): This image was correctly identified as hateful, but the target was misclassified. The model predicted the target was a community (likely due to the words “trans” and “women”), but the ground truth was an individual.

Conclusion and Implications

The MemeCLIP paper offers two substantial contributions to the field of multimodal machine learning.

First, the PrideMM dataset provides a much-needed resource for understanding the complexities of online discourse regarding the LGBTQ+ community. By moving beyond binary labels and including stance and humor, it allows for the development of AI that is more culturally competent and less prone to blanket censorship.

Second, the MemeCLIP framework demonstrates that we don’t always need massive computing power to achieve state-of-the-art results. By strategically adapting a frozen foundation model (CLIP) with lightweight modules like Feature Adapters and Cosine Classifiers, the authors created a highly efficient model that outperforms much larger competitors.

For students of machine learning, this paper is a masterclass in parameter-efficient transfer learning. It shows that with the right architecture, you can adapt general-purpose models to solve highly specific, nuanced, and socially important problems. As the internet continues to evolve, tools like MemeCLIP will be essential in navigating the fine line between free expression, humor, and harmful content.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2409.14703/images/cover.png)