Introduction

The prevailing philosophy in Large Language Model (LLM) pretraining has largely been “more is better.” Models like GPT-4 and Llama-3 are trained on trillions of tokens derived from a massive, indiscriminate sweep of the internet. While this produces impressive general-purpose capabilities, it is exorbitantly expensive and computationally inefficient.

But what if you don’t need a model that knows everything about everything? What if you need a model that excels in a specific domain—like biomedical research or legal reasoning—without spending millions of dollars training on irrelevant web scrapes?

This brings us to the concept of Data Selection. The goal is to identify a subset of training data that is most valuable for your specific target task. However, existing methods face a dilemma: they are either too simple (like keyword matching) and introduce heavy bias, or they are too complex (requiring a whole other neural network to select data) and become computationally intractable.

In the paper Target-Aware Language Modeling via Granular Data Sampling, researchers from Meta AI, Virginia Tech, and Iowa State University propose a novel solution. They revisit a classic statistical technique—Importance Sampling—and supercharge it using Multi-Granular Tokenization. By analyzing text at the level of subwords, whole words, and multi-word phrases simultaneously, they demonstrate that we can train models on just ~1% of the original data while matching the performance of models trained on the full dataset.

Background: The Need for Coreset Selection

To understand the contribution of this paper, we first need to define Coreset Selection. In the context of machine learning, a “coreset” is a small, weighted subset of the original dataset. The idea is that if you train a model on this coreset, it should yield a model approximation close to one trained on the entire dataset.

Selecting this subset usually involves comparing two distributions:

- The Raw Distribution (\(q\)): The massive, uncurated pool of data (e.g., RefinedWeb, CommonCrawl).

- The Target Distribution (\(p\)): A smaller, high-quality dataset representing what you actually want the model to learn (e.g., specific reasoning tasks or domain-specific texts).

The Importance Sampling Approach

A statistically sound way to select this data is Importance Sampling. We assign a weight (\(w_i\)) to every document in the raw dataset. This weight represents how “important” that document is for our target task. Mathematically, this is the ratio of the probability of seeing the document in the target distribution versus the raw distribution:

\[w_i = \frac{p(z_i)}{q(z_i)}\]If a document looks very similar to our target (\(p\) is high) but is rare in the raw data (\(q\) is low), it gets a high weight.

The problem lies in how we represent a “document” (\(z_i\)). If we simply use a bag-of-words (counting word frequency), we lose context. If we use complex neural embeddings, the selection process becomes too slow. This paper argues that the secret sauce lies in how we tokenize the text before calculating these weights.

The Core Method: Multi-Granular Tokenization

The researchers introduce a pipeline that blends the efficiency of n-gram features with the semantic richness of variable-length tokens. This process allows them to select data that is semantically aligned with the target without overfitting or losing general language capabilities.

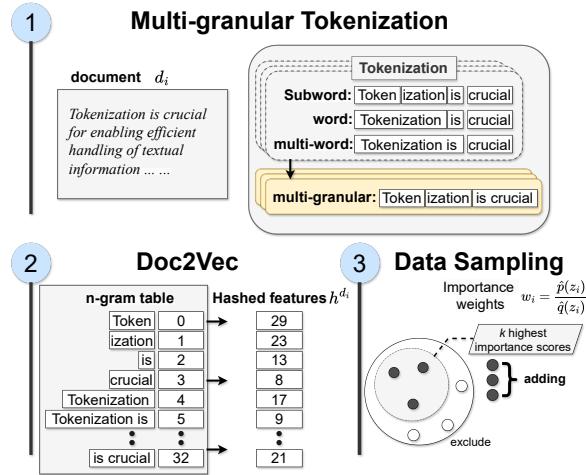

As illustrated in Figure 1, the process consists of three distinct steps: featurization, hashing, and sampling.

1. Multi-Granular Featurization

Standard tokenizers usually break text into subwords (e.g., “Token”, “iz”, “ation”). This is great for vocabulary efficiency but often fragments meaning. Conversely, looking only at whole words can miss morphological nuances.

The authors propose using Multi-Granular Tokens. For a given sentence like “Tokenization is crucial…”, the system generates three types of features simultaneously:

- Subword level: “Tok”, “en”, “iz”, “ation”

- Word level: “Tokenization”, “is”, “crucial”

- Multi-word level: “Tokenization is crucial” (Phrase level)

By capturing all three levels, the model preserves the general information found in coarse tokens (words) while capturing specific domain knowledge found in fine-grained tokens (subwords and phrases).

2. Tokenizer Adaptation and Vocabulary Optimization

How do the researchers decide which subwords or phrases to include? They don’t just use a standard tokenizer. They perform Tokenizer Adaptation.

They start with a standard vocabulary (e.g., Llama-3’s tokenizer) and merge it with a vocabulary learned specifically from the target task data. However, simply smashing two vocabularies together creates redundancy. To solve this, they optimize the vocabulary by minimizing the entropy difference.

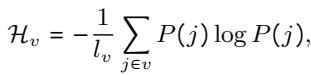

They utilize a vocabulary utility metric, \(\mathcal{H}_{v}\), defined as:

Here, \(P(j)\) is the relative frequency of a token. The goal is to find a vocabulary set \(v(t)\) that minimizes the change in entropy compared to the previous step, effectively finding the most efficient way to represent the target text:

This optimization ensures that the features used for sampling are statistically representative of the target domain.

3. Hashing and Importance Weighting

Once the document is tokenized into this multi-granular soup, it needs to be converted into a mathematical format. The authors use hashing to map these n-grams into a fixed-size vector.

The importance weight \(w_i\) is then calculated. If a document in the massive raw dataset contains a high density of the specific multi-granular tokens found in the target dataset, it receives a high score. Finally, they sample the top \(k\) documents based on these weights to form the training coreset.

Why Granularity Matters: The Bias-Variance Tradeoff

You might wonder: Why go through the trouble of mixing subwords, words, and phrases? Why not just use phrases?

The authors found that relying on a single level of granularity introduces bias.

- Subwords only: Too fragmented; the model loses the semantic “big picture.”

- Phrases only: Too specific; the sampling might overfit to specific sentences in the target data, ignoring documents that are topically relevant but phrased differently.

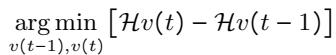

By mixing granularities, they reduce the KL Divergence (a measure of how different two probability distributions are) between the selected data and the target data.

Figure 2 visualizes this correlation. The x-axis shows the reduction in KL divergence (better alignment with target), and the y-axis shows accuracy on the HellaSwag benchmark. The red star (Multi-granular) sits at the top right, indicating that this method achieves the best alignment with the target distribution and, consequently, the highest downstream accuracy.

Experimental Results

The researchers validated their approach by training decoder-only transformer models ranging from 125 million to 1.5 billion parameters. They used the massive RefinedWeb dataset as the raw source and selected roughly 1% of the data (~700 million tokens) based on eight common sense reasoning tasks (like ARC, PIQA, and HellaSwag).

Performance Comparison

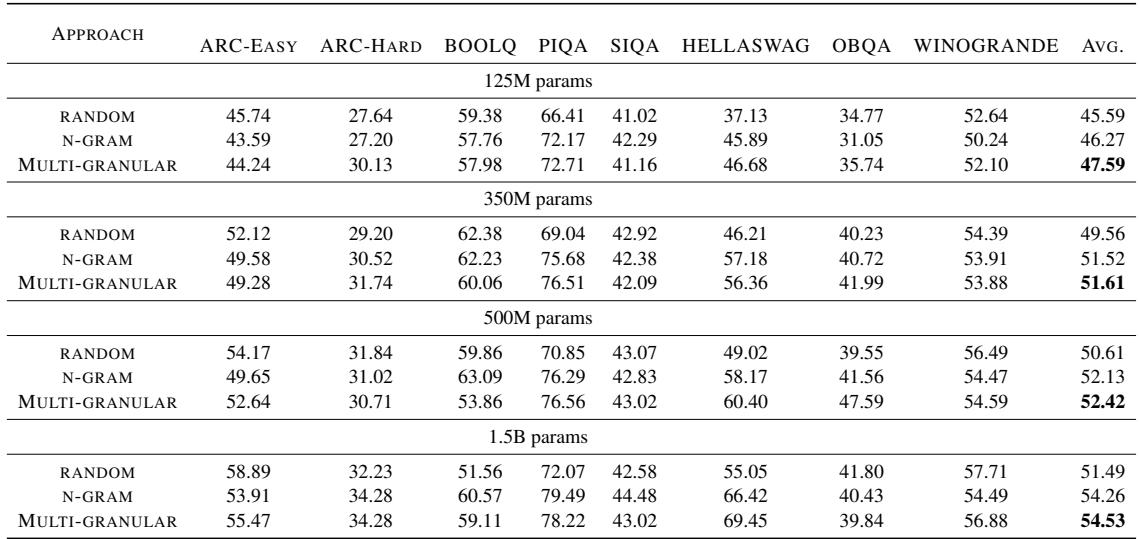

The results, summarized in Table 1, are compelling.

There are two key takeaways from this table:

- Consistent Superiority: Across almost all model sizes, the Multi-Granular approach outperforms both Random sampling and standard N-gram sampling.

- Scaling Efficiency: Even at 1.5 billion parameters, the Multi-Granular models (trained on just 1% of data) achieve an average score of 54.53, significantly higher than the Random baseline (51.49).

Emergent Capabilities

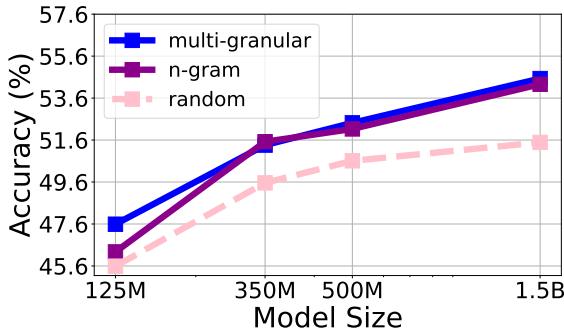

One of the fascinating aspects of LLMs is “emergence”—capabilities that suddenly appear as models get larger. Figure 3 tracks the zero-shot performance averaged across eight tasks.

Notice the trend lines. The Multi-granular line (top) consistently leads. Interestingly, there is a sharp improvement around the 350M parameter mark, suggesting that the benefits of high-quality data selection become even more pronounced as the model gains enough capacity to exploit that data.

Robustness Against Domain Bias

A major risk in targeted data selection is “catastrophic forgetting” or “tunnel vision.” If you select data based heavily on scientific papers, the model might forget how to chat casually.

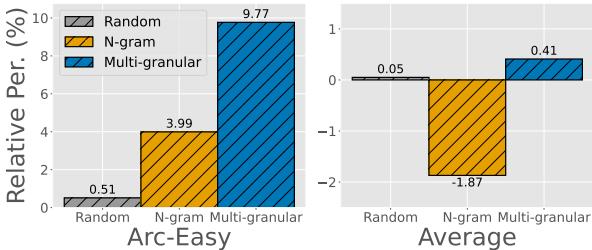

The authors tested this by selecting data based on a single target task (e.g., ARC-Easy) and then testing the model on all tasks.

Figure 4 displays the relative performance. The Multi-granular method (blue bars) shows a massive relative improvement on the target task (ARC-Easy) compared to baselines. Crucially, looking at the “Average” chart on the right, it maintains positive performance gains across the board. This indicates that multi-granular features capture enough general linguistic structure to prevent the model from becoming useless on non-target tasks.

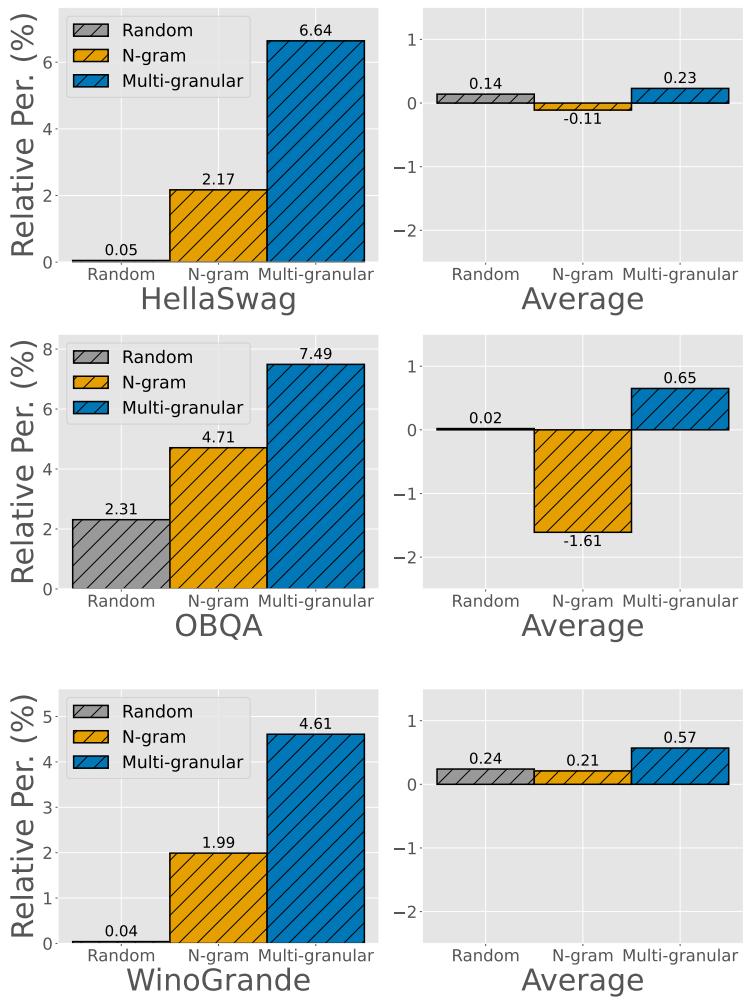

This robustness is further supported by additional experiments on other datasets. For instance, Figure 5 shows the same pattern when HellaSwag, OBQA, or WinoGrande are used as the targets.

In every case, the multi-granular selection (blue) yields the highest relative performance gain, proving that the method is not a fluke specific to one dataset.

Conclusion

The research presented in Target-Aware Language Modeling via Granular Data Sampling offers a practical path forward for efficient LLM training. By moving beyond simple word counts and embracing multi-granular tokenization, we can construct “coresets” that are dense with relevant information yet broad enough to support general reasoning.

For students and practitioners, the implications are clear:

- Data > Compute: You don’t always need more GPUs; sometimes you just need better data selection algorithms.

- Granularity Matters: How you represent your text features (subword vs. phrase) fundamentally changes what your sampling algorithm “sees” and selects.

- Efficiency is Reachable: Training competitive models on 1% of the data is not just theoretical—it is achievable with the right statistical sampling techniques.

As we move toward an era of specialized models and resource-constrained environments, techniques like Multi-Granular Importance Sampling will likely become standard tools in the NLP engineer’s toolkit.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2409.14705/images/cover.png)