Introduction

Mental health counseling is a domain where every word matters. In a typical session, a therapist must balance two critical tasks: actively listening to the client to build a therapeutic bond, and meticulously documenting the session for future reference. This documentation, known as a “counseling note” or summary, is essential for tracking progress and ensuring continuity of care. However, the cognitive load of taking notes can distract the therapist, potentially weakening the connection with the client.

This scenario presents a perfect use case for Artificial Intelligence. If an AI could listen to the session and automatically generate a precise, clinically relevant summary, therapists could focus entirely on their clients. However, despite the explosive growth of Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 or Llama-2, they struggle significantly in this specific arena. General-purpose LLMs often hallucinate facts, miss subtle clinical cues, or fail to structure the note in a way that professionals use.

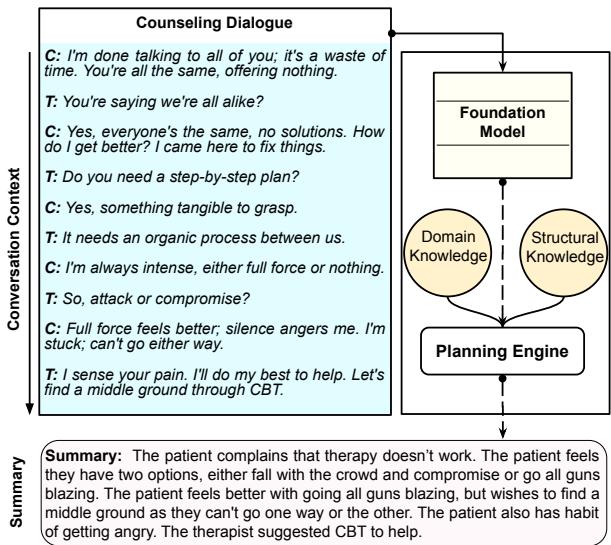

The gap lies in planning. A human expert doesn’t just transcribe; they filter information, align it with medical knowledge, and structure it logically. To bridge this gap, researchers have introduced PIECE (Planning Engine for Counseling Note Generation). This new framework forces the LLM to “plan” its output using domain-specific and structural knowledge before it generates a single word.

As illustrated above, rather than a direct input-to-output process, PIECE interjects a planning phase that organizes patient complaints and therapeutic techniques into a structured summary.

The Challenge: Why Standard LLMs Fail in Counseling

To understand why a specialized system is necessary, one must look at how standard LLMs operate. Most foundational models are trained on vast amounts of general internet text. When asked to summarize a therapy session, they might produce a text that reads fluently but lacks clinical validity.

There are two main hurdles:

- Domain Knowledge: Mental health discussions involve specific terminologies (e.g., distinguishing between a “low mood” and “clinical depression” based on PHQ-9 criteria). Standard LLMs treat all text with roughly equal weight, often keeping “filler” conversation while missing critical symptoms.

- Structural Nuance: A counseling session is a dialogue with a specific flow—introductory pleasantries, symptom discovery, reflection, and intervention. A flat summarization often loses the “geometry” or the directional flow of this conversation.

The researchers argue that to generate high-quality counseling notes, we cannot rely solely on the generative power of an LLM. We need a “Planning Engine” that acts as a sophisticated filter and architect, guiding the LLM on what to say and how to organize it.

The PIECE Architecture

The PIECE framework is built upon a foundational model (specifically MentalLlama, a version of Llama-2 tuned for mental health), but it augments it with a novel two-stream planning engine.

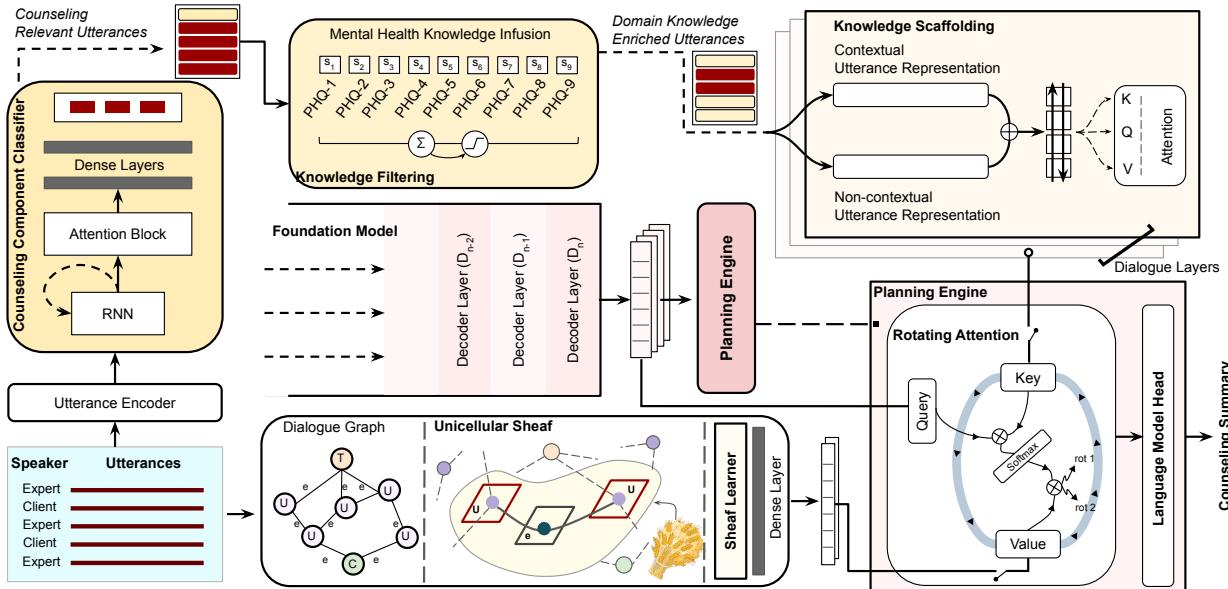

As shown in the architecture diagram, the system processes the input dialogue through two distinct pathways before the final generation:

- Domain Knowledge Encapsulation (Left Stream): Filters and enriches the content based on medical relevance.

- Structural Knowledge Encapsulation (Right Stream): Analyzes the mathematical structure of the conversation using Graph Theory (specifically Sheaf Learning).

These two streams converge in the Planning Engine, which fuses the insights and feeds them into the Language Model Head for the final output. Let us break down these components.

1. Domain Knowledge Encapsulation

This module ensures that the summary contains clinically relevant information and discards noise. It operates in two steps: Filtering and Scaffolding.

Knowledge Filtering: Real-world conversation is messy. It is filled with “Ums,” “Ahs,” and irrelevant small talk (“Discussion Fillers”). The system first uses a Counseling Component Classifier (based on a GRU-RNN) to tag each utterance. It identifies whether a sentence is about Symptoms (SH), Patient Discovery (PD), or Reflecting (RT). Irrelevant fillers are masked out.

Furthermore, the system cross-references utterances with the PHQ-9 lexicon (a standard tool for diagnosing depression severity). If an utterance has high similarity to PHQ-9 terms, it is flagged as high-priority domain knowledge.

Knowledge Scaffolding: Filtering isn’t enough; the model needs to understand the context of these medical terms. The researchers use a scaffolding technique that combines contextual embeddings (from BERT) and non-contextual embeddings (from GloVe). These are processed through a Bi-LSTM to create a rich representation of the medical facts.

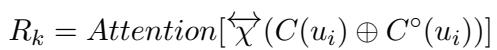

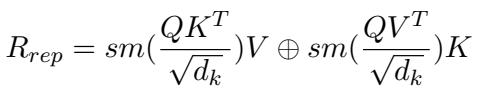

The attention mechanism for this scaffolding is defined mathematically as:

In this equation, \(C(u_i)\) represents the contextual BERT embeddings, and \(C^\circ(u_i)\) represents the non-contextual GloVe embeddings. By concatenating (\(\oplus\)) these and passing them through an attention mechanism, the system creates a representation (\(R_k\)) that is dense with domain-specific meaning.

2. Structural Knowledge Encapsulation via Sheaf Learning

This is perhaps the most mathematically innovative part of the paper. Standard Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) can model dialogues by treating utterances as nodes and their sequence as edges. However, standard graphs struggle to capture the complex “geometry” of a conversation—how the meaning shifts and evolves relative to the participants.

To solve this, the researchers employ Sheaf Theory. In topology, a “Sheaf” allows you to associate data (vector spaces) to the nodes and edges of a graph in a way that preserves local geometry. It allows the model to understand not just that Utterance A follows Utterance B, but how the information space transitions between them.

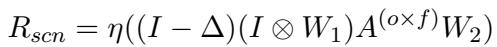

The system constructs a dialogue graph where utterances are nodes. It then applies a Sheaf Convolution Network (SCN) to learn the structural representations (\(R_{scn}\)).

Here, \(\Delta\) is the Sheaf Laplacian (a matrix representing the geometry of the graph), and \((I \otimes W_1)\) represents the learnable weights. This equation essentially diffuses information across the graph, allowing the model to learn the “shape” of the conversation. The output is a set of representations that encode the structural flow of the therapy session.

3. The Planning Engine: Rotating Attention

Now the system possesses two distinct types of “knowledge”:

- \(R_k\): The medical facts (Domain Knowledge).

- \(R_s\): The conversational flow (Structural Knowledge).

The Planning Engine must fuse these with the Foundation Model’s own understanding. It does this using a Rotating (Cyclic) Attention Mechanism.

Standard attention mechanisms in Transformers use Queries (Q), Keys (K), and Values (V). Usually, these all come from the same source. In PIECE, the “Query” comes from the Foundation Model (the LLM’s current state), but the Keys and Values are swapped between the Domain and Structural representations in a rotating cycle.

As the equation describes, the model computes attention twice per cycle. In one pass, the Structural Knowledge might act as the Key/Value. In the next, the Domain Knowledge takes that role. The results are concatenated (\(\oplus\)). This forces the LLM to pay equal attention to what was said (medical facts) and how it fits into the story (structure), preventing the generation from becoming a disjointed list of symptoms or a fluent but empty paragraph.

Experimental Results

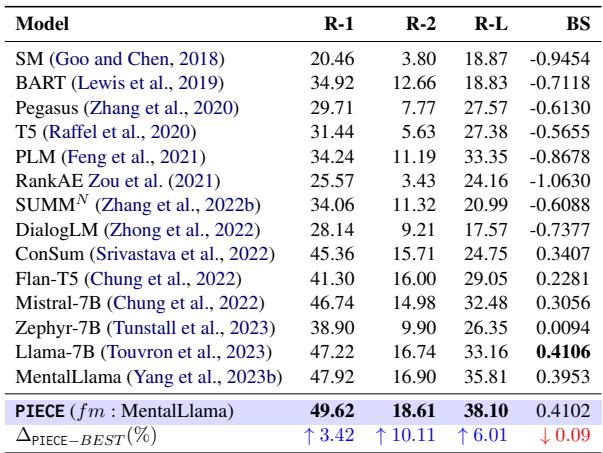

The researchers evaluated PIECE using the MEMO dataset, which contains transcripts of counseling sessions and expert-written summaries. They compared PIECE against 14 baseline models, ranging from standard sequence-to-sequence models (like BART and T5) to modern LLMs (Llama-2, Mistral, Zephyr).

Quantitative Performance

The primary metrics used were ROUGE (which measures text overlap with the “gold standard” human summary) and BLEURT (a learned metric that judges semantic meaning).

The results in Table 1 are compelling. PIECE (using MentalLlama as a base) outperforms all baselines.

- ROUGE-2: A 10.11% improvement over the best baseline. ROUGE-2 measures bigram overlap, suggesting PIECE is much better at capturing specific phrases and concepts used by human experts.

- ROUGE-L: A 6.01% improvement. This measures the longest common subsequence, indicating better sentence structure coherence.

It is worth noting that while Llama-7B had a slightly higher BLEURT score in isolation, PIECE’s massive gains in ROUGE indicate it is far more faithful to the specific content requirements of medical summaries.

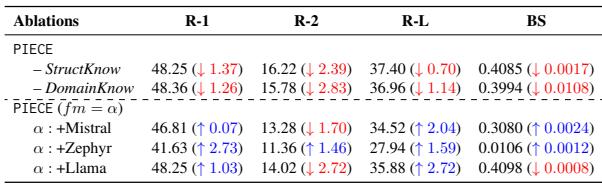

Why Does Planning Matter? (Ablation Study)

To prove that the complex architecture was actually necessary, the researchers performed an ablation study, removing parts of the system to see how performance dropped.

Table 2 reveals two critical insights:

- Removing Knowledge Hurts: When the Domain Knowledge module was removed (leaving only the structural and base model), performance dropped significantly (R-2 dropped by 2.83 points).

- Generalizability: The researchers applied the PIECE planning engine to other LLMs (Mistral, Zephyr, Llama). in almost every case, adding the planning engine improved the base model’s performance. This suggests that the “Planning” concept is universal and not just a quirk of one specific model.

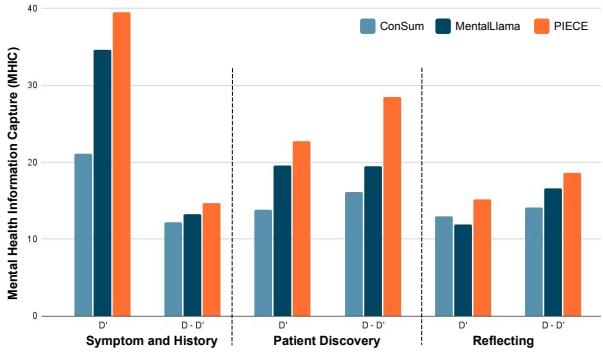

Capturing Mental Health Information

General metrics like ROUGE don’t tell the whole story. A summary could be grammatically perfect but miss the fact that a patient is suicidal. The researchers used a domain-specific metric called Mental Health Information Capture (MHIC), which measures how well the summary captures specific counseling components like Symptoms or Patient Discovery.

Figure 3 shows a stark contrast. The orange bars (PIECE) consistently reach higher MHIC scores across all categories compared to MentalLlama (dark blue) and ConSum (light blue). This confirms that the “Filtering and Scaffolding” phase is successfully forcing the model to retain critical clinical details.

Expert Human Evaluation

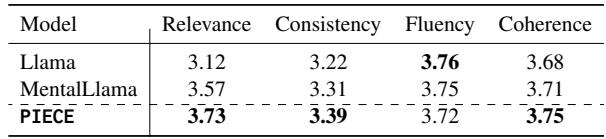

In clinical AI, automated metrics are not enough. A panel of clinical psychologists and linguists evaluated the summaries.

Linguistic Quality: Evaluators rated summaries on Relevance, Consistency, Fluency, and Coherence.

PIECE achieved the highest scores in Relevance (3.73), verifying that the planning engine successfully prioritized the right information. It also tied or beat baselines on Coherence, likely thanks to the Sheaf-based structural learning.

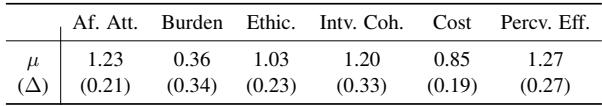

Clinical Acceptability: A clinical psychologist with over 10 years of experience assessed the summaries using a clinical acceptability framework.

The expert evaluation (Table 5) was highly positive. On “Perceived Effectiveness,” the model scored well, with the expert noting that in 56.3% of cases, PIECE outperformed the competitive MentalLlama model. Crucially, the expert found “negligible” hallucinations in 75% of instances, a massive win for safety in healthcare AI.

Conclusion and Future Implications

The PIECE framework demonstrates a pivotal shift in how we approach Large Language Models for specialized domains. Rather than simply making models larger or training them on more text, this research highlights the power of inference-time planning.

By explicitly separating the tasks of “understanding the medical facts” (Domain Knowledge) and “understanding the conversation flow” (Structural Knowledge), and then fusing them via a Planning Engine, PIECE generates counseling summaries that are not just fluent, but clinically useful.

Key Takeaways:

- Plan before you write: Injecting a planning phase allows LLMs to handle complex, unstructured dialogues better.

- Structure matters: Mathematical modeling of conversation geometry (Sheaf Learning) improves the coherence of generated text.

- Safety first: This approach significantly reduces hallucinations, making it a viable candidate for assistive tools in mental health care.

While the authors emphasize that this is an assistive tool for clinicians—not a replacement—it represents a significant step toward AI systems that can reliably handle the nuance and sensitivity of human mental health.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2409.14907/images/cover.png)