Imagine you are at a dinner party. You meet someone new, and within ten minutes, you think to yourself, “This person is extremely extroverted.”

But why did you think that?

Was it because they spoke loudly? Was it because they initiated the conversation? Or perhaps it was because they were waving their hands enthusiastically while telling a story? As humans, we don’t just assign labels to people; we subconsciously gather evidence, analyze behaviors in specific moments, and look for patterns over time to form an impression of someone’s personality.

For years, Artificial Intelligence has attempted to replicate this via Automatic Personality Recognition (APR). However, most existing models operate like a “black box.” You feed them a user’s social media posts or dialogue logs, and the model spits out a label: Neuroticism: High.

But it doesn’t tell you why.

This lack of explainability is a significant hurdle. If an AI helps a recruiter screen candidates or assists a psychologist in diagnosis, “trust me, I’m an algorithm” isn’t a good enough explanation.

In a fascinating new paper, “Revealing Personality Traits: A New Benchmark Dataset for Explainable Personality Recognition on Dialogues,” researchers Lei Sun, Jinming Zhao, and Qin Jin propose a shift in how we approach this field. They introduce a framework that doesn’t just guess your personality type but explains the reasoning process behind it, moving from specific behaviors to temporary states, and finally to long-term traits.

In this deep dive, we will explore their novel framework, the massive dataset they built to support it, and what their experiments reveal about the capabilities of modern Large Language Models (LLMs).

The Psychology of the “Why”

To understand the researchers’ contribution, we first need a quick refresher on the psychological theory underpinning their work: the Big Five Personality Model (often remembered by the acronym OCEAN).

- Openness: Curiosity, appreciation for art, emotion, adventure.

- Conscientiousness: Self-discipline, achievement-striving, dutifulness.

- Extraversion: Energy, positive emotions, surgency, assertiveness.

- Agreeableness: Compassionate and cooperative rather than suspicious and antagonistic.

- Neuroticism: The tendency to experience unpleasant emotions easily, such as anger, anxiety, depression, or vulnerability.

Traits vs. States

The crucial insight utilized in this paper is the distinction between a Personality Trait and a Personality State.

- Traits are enduring patterns. They are the “long-term” definition of who you are.

- States are short-term. They are characteristic patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in a specific moment.

An introverted person (Trait) can exhibit extroverted behavior (State) at a party if they are trying to network. A generally calm person (Trait) can have a moment of high anxiety (State) during a crisis.

The authors argue that to accurately recognize and explain a personality trait, an AI must first identify these short-term states and the evidence supporting them, and then aggregate that information to determine the stable trait.

The Core Method: Chain-of-Personality-Evidence (CoPE)

Current research usually treats personality recognition as a simple classification task: Input Text \(\rightarrow\) Output Label. The authors contend that this skips the reasoning process.

They propose a new framework called Chain-of-Personality-Evidence (CoPE). This framework mimics the human cognitive process of observing specific details and reasoning upwards toward a conclusion.

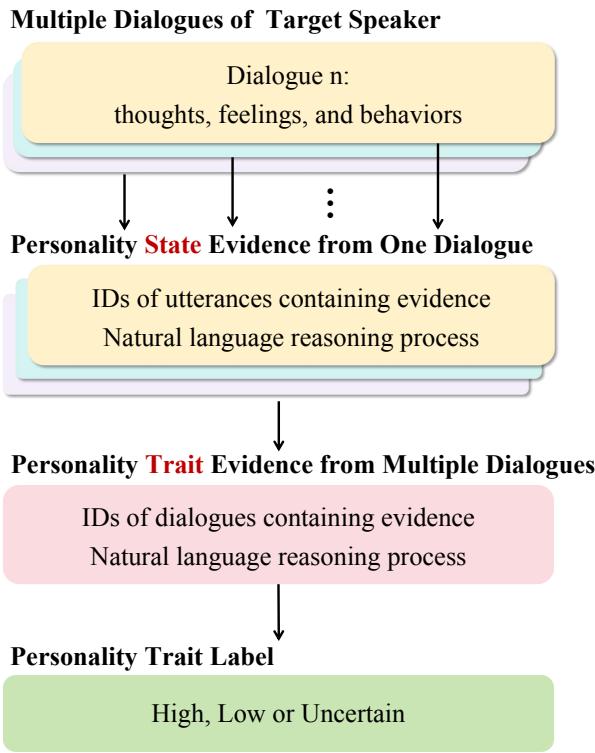

As illustrated in Figure 1, the CoPE framework operates on a hierarchical structure:

- Input: The process begins with Multiple Dialogues from a target speaker. Personality isn’t revealed in a single sentence; it requires context across time.

- State Evidence: For each individual dialogue, the system identifies specific Utterance IDs (sentences) that serve as evidence. It uses natural language reasoning to infer the Personality State for that specific situation.

- Trait Evidence: The system doesn’t stop at the state level. It aggregates evidence from multiple dialogues. It looks at the patterns of states to form Personality Trait Evidence.

- Output: Finally, based on the accumulated evidence, it assigns a Personality Trait Label (High, Low, or Uncertain).

This “chain” ensures that the final prediction is grounded in specific moments. If the model says a speaker is “High in Conscientiousness,” it can point to specific dialogues where the speaker made plans, double-checked work, or arrived early, and explain how those momentary states contribute to the overall trait.

Constructing the PersonalityEvd Dataset

To train models on this new framework, the researchers needed data. You can’t just download “explained personalities” from the internet; they had to build it. They created PersonalityEvd, a dataset constructed from Chinese TV series dialogues (specifically the CPED corpus).

Why TV shows? Scripted characters have consistent, exaggerated personalities designed to be recognizable, making them excellent subjects for training models to spot personality markers.

The Annotation Process

The creation of PersonalityEvd was a massive undertaking involving a “human-in-the-loop” process.

- Source Material: They selected 72 speakers and analyzed roughly 30 dialogues per speaker.

- Reasoning Annotations: They didn’t just want labels; they wanted the reasoning. They used the BFI-2 scale (a standard psychological questionnaire) as a guideline.

- GPT-4 Assistance: To handle the workload, they first used GPT-4 to generate pre-annotations. GPT-4 analyzed dialogues to predict states and draft reasoning evidence.

- Human Correction: This is the critical quality control step. Psychology students reviewed the AI’s work, correcting mistakes, refining the evidence, and ensuring the reasoning was sound.

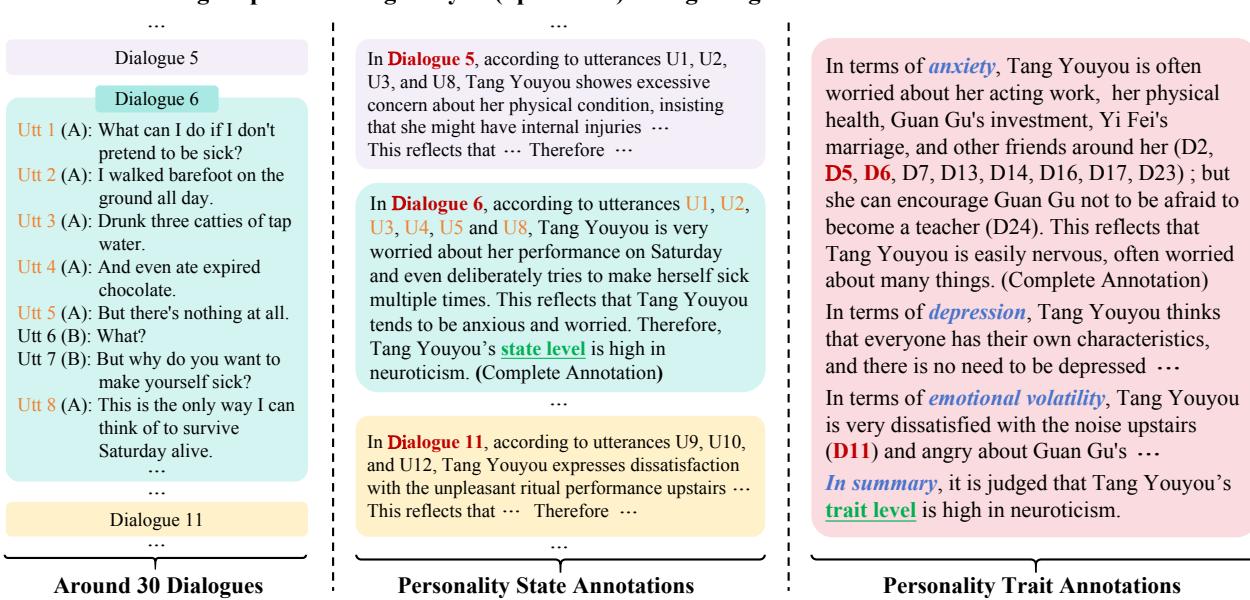

Figure 2 above provides a stunning example of what a single entry in this dataset looks like. Let’s break it down:

- Left Column (Input): We see snippets from Dialogue 5, 6, and 11 for a character named “Tang Youyou.” In Dialogue 6, she talks about drinking tap water and eating expired chocolate to make herself sick.

- Middle Column (State Level): The annotators identify specific utterances (U#) and explain the Personality State. For Dialogue 6, the reasoning notes that her deliberate attempt to get sick reflects “high neuroticism due to being anxious and worried.”

- Right Column (Trait Level): This aggregates the findings. It breaks Neuroticism down into facets like Anxiety, Depression, and Emotional Volatility. It synthesizes the evidence from the various dialogues to conclude that Tang Youyou’s trait level is High.

This granular level of annotation—linking a specific sentence (U#12) to a specific state, which then supports a specific facet of a trait—is what makes this dataset unique.

Dataset Statistics and Insights

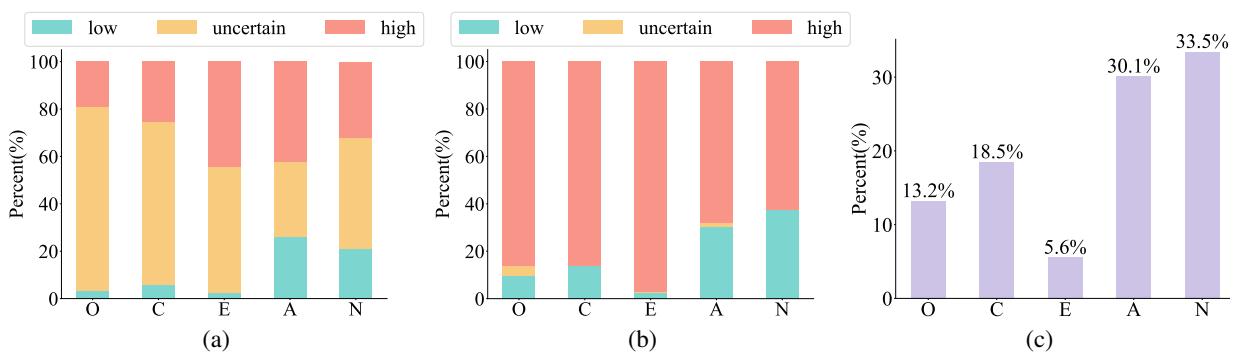

The final dataset contains 1,924 dialogues and over 32,000 utterances. But beyond the raw numbers, the distribution of the data reveals something interesting about human (or character) nature.

Figure 3 highlights the complexity of the task. Look at chart (a), the distribution of State Labels. You’ll notice a massive amount of “Uncertain” (yellow) sections. This makes sense—in any given conversation, you aren’t necessarily displaying your personality traits strongly. You might just be ordering coffee.

However, look at chart (b), the Trait Labels. Here, the “Uncertain” portion shrinks significantly. While individual moments might be ambiguous, the sum of a person’s interactions usually paints a clear picture.

Most interestingly, chart (c) shows the “Ratio of state label different from trait label.” This confirms the “Trait vs. State” theory. A significant percentage of the time, a person’s behavior in a specific moment does not match their overall personality trait. An agreeableness-dominant person can have a disagreeable argument. A model that ignores this distinction would likely fail.

Visualizing Personality

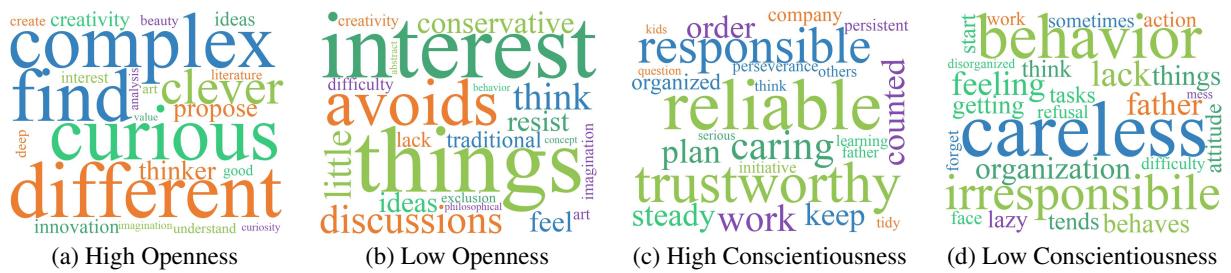

To get a sense of what the “Reasoning Process” looks like in the dataset, the authors generated word clouds based on the text evidence.

In Figure 4, we see the vocabulary of personality.

- High Openness (a): Words like complex, creative, curious, ideas, and imagination dominate.

- Low Conscientiousness (d): We see words like careless, irresponsible, lazy, mess, and forget.

These word clouds validate that the dataset is capturing the correct semantic concepts associated with the Big Five traits.

Two New Tasks: EPR-S and EPR-T

The researchers defined two distinct tasks for future AI models to solve using this dataset:

1. Evidence grounded Personality State Recognition (EPR-S)

The Goal: Given a single dialogue, predict the speaker’s personality state (High, Low, or Uncertain) regarding a specific dimension (e.g., Extraversion). The Requirement: The model must also output the evidence:

- Which utterances (sentences) led to this conclusion?

- A natural language explanation (reasoning) of why those sentences indicate that state.

2. Evidence grounded Personality Trait Recognition (EPR-T)

The Goal: Given a set of multiple dialogues (historical context), predict the speaker’s long-term personality trait. The Requirement: The model must provide:

- Which dialogues were most relevant?

- A synthesized explanation covering the different facets of that trait.

This second task is significantly harder. It involves handling conflicting evidence (the “nice person having a bad day” problem) and processing a much larger context window.

Experiments: How do LLMs Perform?

The authors benchmarked three major Large Language Models on these tasks: ChatGLM3-6B, Qwen1.5-7B, and GPT-4-Turbo.

They used Chain-of-Thought (CoT) fine-tuning. This means they trained the models (or prompted them, in GPT-4’s case) to generate the reasoning evidence before generating the final label, forcing the model to “think” through the problem.

The Results

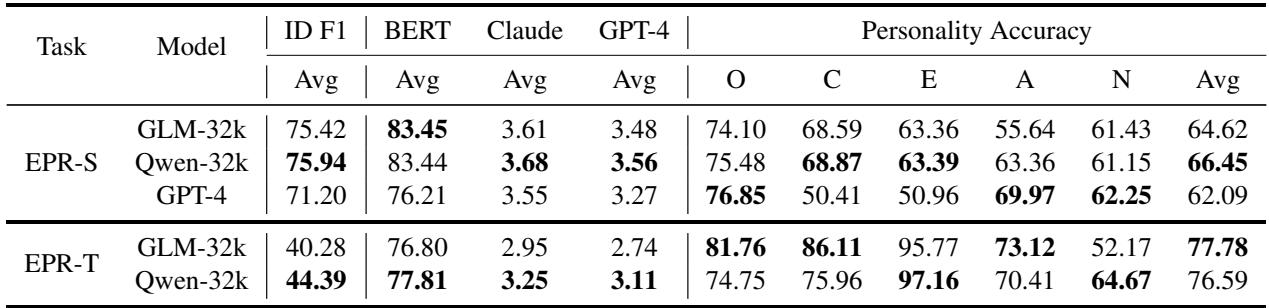

Table 2 reveals the current state of the art. Here is how to read it:

- ID F1: How accurately the model identified the specific sentences/dialogues that served as evidence.

- BERT / Claude / GPT-4 (Score): These measure the quality of the generated text explanation compared to the human ground truth.

- Personality Accuracy: Did the model guess the final label (High/Low/Uncertain) correctly?

Key Takeaways:

- It’s Difficult: The accuracy scores for the Trait task (EPR-T) hover between 52% and 64% on average (Avg column, bottom right). This shows that despite the power of modern LLMs, explaining personality remains a complex challenge.

- Qwen and GLM are Competitive: The fine-tuned smaller models (ChatGLM and Qwen) performed admirably against GPT-4 in several metrics, particularly in identifying evidence (ID F1).

- GPT-4’s Zero-Shot Performance: Even without fine-tuning, GPT-4 showed strong reasoning capabilities, though it sometimes lagged in pure accuracy compared to models trained specifically on this data.

The Value of Evidence

One of the most important questions the researchers asked was: Does forcing the model to explain itself actually make it more accurate?

They performed an ablation study (removing parts of the system to see what happens). They compared Direct prediction (just guessing the label) against CoT (generating evidence first).

For the State Recognition task, introducing evidence (Hybrid training) improved performance by about 2%. This suggests that when an LLM is forced to articulate the “thoughts, feelings, and behaviors” of a speaker, it forms a better understanding of the personality state.

The Pipeline Approach: State \(\rightarrow\) Trait

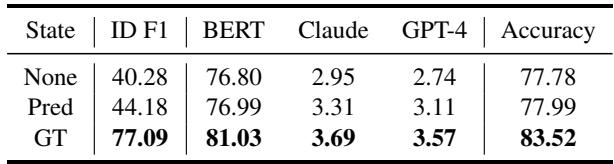

The researchers also tested whether knowing the State helps predict the Trait.

Table 5 shows the results of this experiment.

- None: The model is just given raw dialogues.

- Pred: The model is given the dialogues + the predicted states (what the model thinks the states are).

- GT: The model is given the dialogues + the Ground Truth states (the correct human annotations).

The jump in performance from “None” to “GT” is massive (from 77.78% to 83.52% accuracy). Even using the model’s own predicted states (“Pred”) offered a slight improvement.

This confirms the authors’ hypothesis: The path to understanding personality traits lies in accurately understanding momentary states. If we can build models that are better at recognizing immediate states (EPR-S), we will naturally get better at recognizing long-term traits (EPR-T).

Conclusion: A Step Toward Empathetic AI

The work by Sun, Zhao, and Jin represents a maturity in the field of affective computing. We are moving past the era of simple classification, where an AI assigns a personality label based on hidden patterns in data. We are entering an era of Explainable AI (XAI), where the system must justify its conclusions.

The PersonalityEvd dataset provides the community with a challenging benchmark. It requires models to perform complex reasoning, handle contradictions between short-term behaviors and long-term traits, and articulate psychological concepts in natural language.

While current models struggle to match human-level performance on these tasks, the CoPE framework offers a roadmap for improvement. By mimicking the human process of gathering evidence and distinguishing between temporary states and permanent traits, we move closer to AI that can truly “understand” the complexity of human personality—not just label it.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2409.19723/images/cover.png)