Imagine you are asking a smart assistant to rank three job candidates: Alice, Bob, and Charlie. You ask the assistant, “Is Alice better than Bob?” It says yes. You ask, “Is Bob better than Charlie?” It says yes. Logically, you’d expect that if Alice beats Bob, and Bob beats Charlie, then Alice must beat Charlie.

But when you ask, “Is Alice better than Charlie?” the assistant pauses and says, “No, Charlie is better than Alice.”

You have just encountered a logical inconsistency. Specifically, a violation of transitivity.

This scenario isn’t hypothetical. It is a pervasive issue in state-of-the-art Large Language Models (LLMs). While we often focus on “hallucinations” (inventing facts) or “alignment” (refusing harmful requests), there is a deeper, structural problem: LLMs often lack the fundamental logical consistency required for reliable decision-making.

In the research paper “Aligning with Logic,” researchers tackle this problem head-on. They propose a rigorous framework to measure just how illogical our current models are, and they introduce a novel method called REPAIR to force models to think more consistently.

In this deep dive, we will explore the mathematics of consistency, diagnose why models fail, and look at how we can mathematically “repair” a model’s intuition to make it logically robust.

The Reliability Crisis

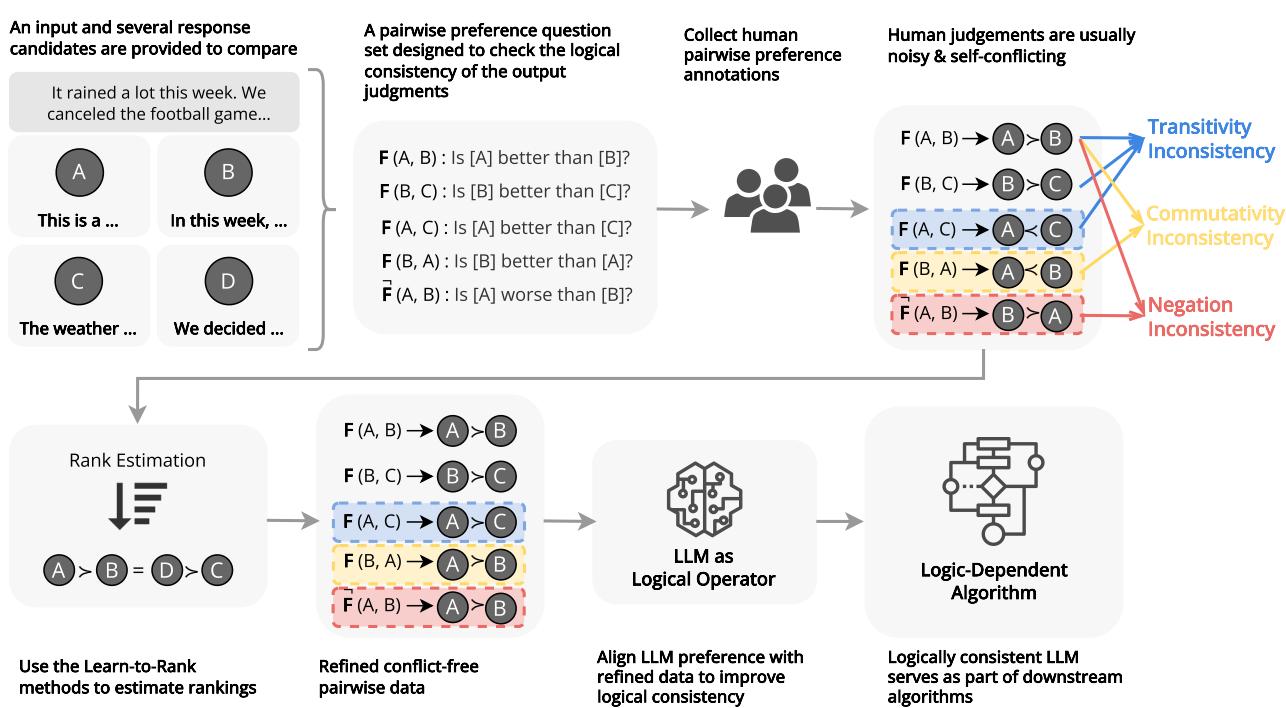

Why does logical consistency matter? If you are just using ChatGPT to write a poem, it probably doesn’t. But LLMs are increasingly being used as operators in complex systems. They are being used to re-rank search results, evaluate code quality, and order temporal events in narratives.

In these “Logic-Dependent” algorithms, the LLM acts as a function. It takes two inputs and outputs a relationship (e.g., \(A > B\)). If that function is erratic—if it says \(A > B\) on Tuesday but \(B > A\) on Wednesday, or if it violates basic logic rules—the entire algorithm collapses.

The researchers identify three pillars of logical preference consistency:

- Transitivity: The chain of reasoning must hold (\(A > B > C \implies A > C\)).

- Commutativity: The order of inputs shouldn’t matter (\(A\) vs \(B\) should yield the same result as \(B\) vs \(A\)).

- Negation Invariance: “A is better than B” must be semantically equivalent to “B is worse than A.”

Let’s break these down and see how the paper quantifies them.

Part 1: Measuring the Madness

To treat the patient, we first need to diagnose the disease. The researchers treat the LLM as an operator function \(F(x_i, x_j)\) which compares two items and outputs a decision.

1. Transitivity: The Circle of Confusion

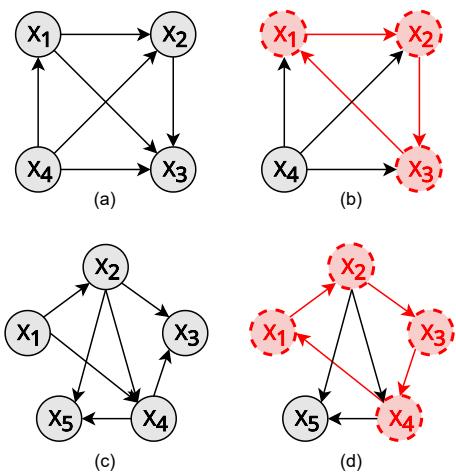

Transitivity is the bedrock of ranking. Without it, you cannot sort a list. If an LLM prefers A to B, B to C, and C to A, it has created a cycle. In graph theory, a perfectly consistent set of preferences forms a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG)—a graph with no loops.

As shown in Figure 2, a transitive relationship looks like a hierarchy (Graphs a, b, c). A violation looks like a cycle (Graph d). The researchers propose a metric, \(s_{tran}(K)\), to measure this.

Because checking every possible combination of items in a large dataset is computationally impossible (the number of combinations explodes exponentially), they sample sub-graphs of size \(K\) (e.g., subsets of 3 or 5 items).

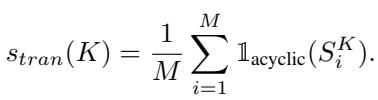

The metric is defined as the probability that a random sub-graph of size \(K\) contains no cycles:

Here, \(\mathbb{1}_{\mathrm{acyclic}}\) is a function that returns 1 if the subgraph is a valid hierarchy (no loops) and 0 if it contains a contradiction. A score of 1.0 means the model is perfectly hierarchical in its reasoning. A lower score indicates a confused model.

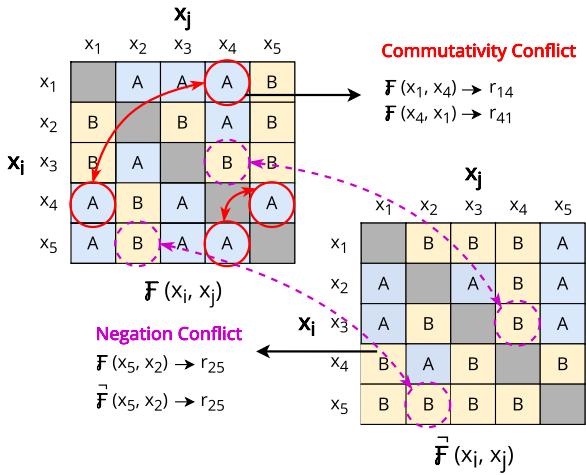

2. Commutativity: The “First is Best” Bias

LLMs have a known psychological quirk: positional bias. They often prefer the first option presented to them, or sometimes the second, regardless of the content.

Commutativity demands that \(F(A, B)\) yields the same logical outcome as \(F(B, A)\). If the model says “Option A is better” when A is first, it should say “Option B is worse” (which implies A is better) when B is first. If it changes its mind just because you swapped the order, it lacks commutativity.

The researchers visualize this in Figure 3 (left matrix). The red circles show a conflict where the model’s judgment flips based on position.

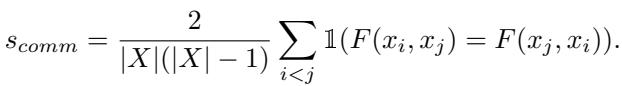

They define the commutativity score \(s_{comm}\) as the percentage of pairs where the model stays consistent regardless of order:

3. Negation Invariance: Understanding “Not”

This is a linguistic logic check. If I ask, “Is A better than B?” and you say “Yes,” then if I ask, “Is A worse than B?”, you must say “No.”

Surprisingly, LLMs struggle with this. They might agree that A is better than B, but also agree that A is worse than B if prompted differently. This property is measured by checking if the model’s judgment on the standard question matches the logical negation of the judgment on the negative question.

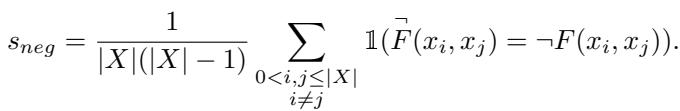

To test this, the researchers used prompt templates that explicitly ask the model to judge “better” versus “worse,” as seen below:

Part 2: The Diagnosis (Experimental Results)

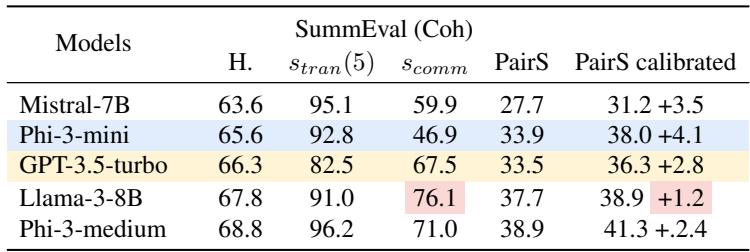

The researchers ran these tests on popular models (Llama-2, Llama-3, Mistral, GPT-3.5) across three distinct tasks:

- SummEval: Judging which of two text summaries is more coherent.

- NovelEval: Judging which of two documents is more relevant to a query.

- CaTeRS: Determining the temporal order of events (Did Event A happen before Event B?).

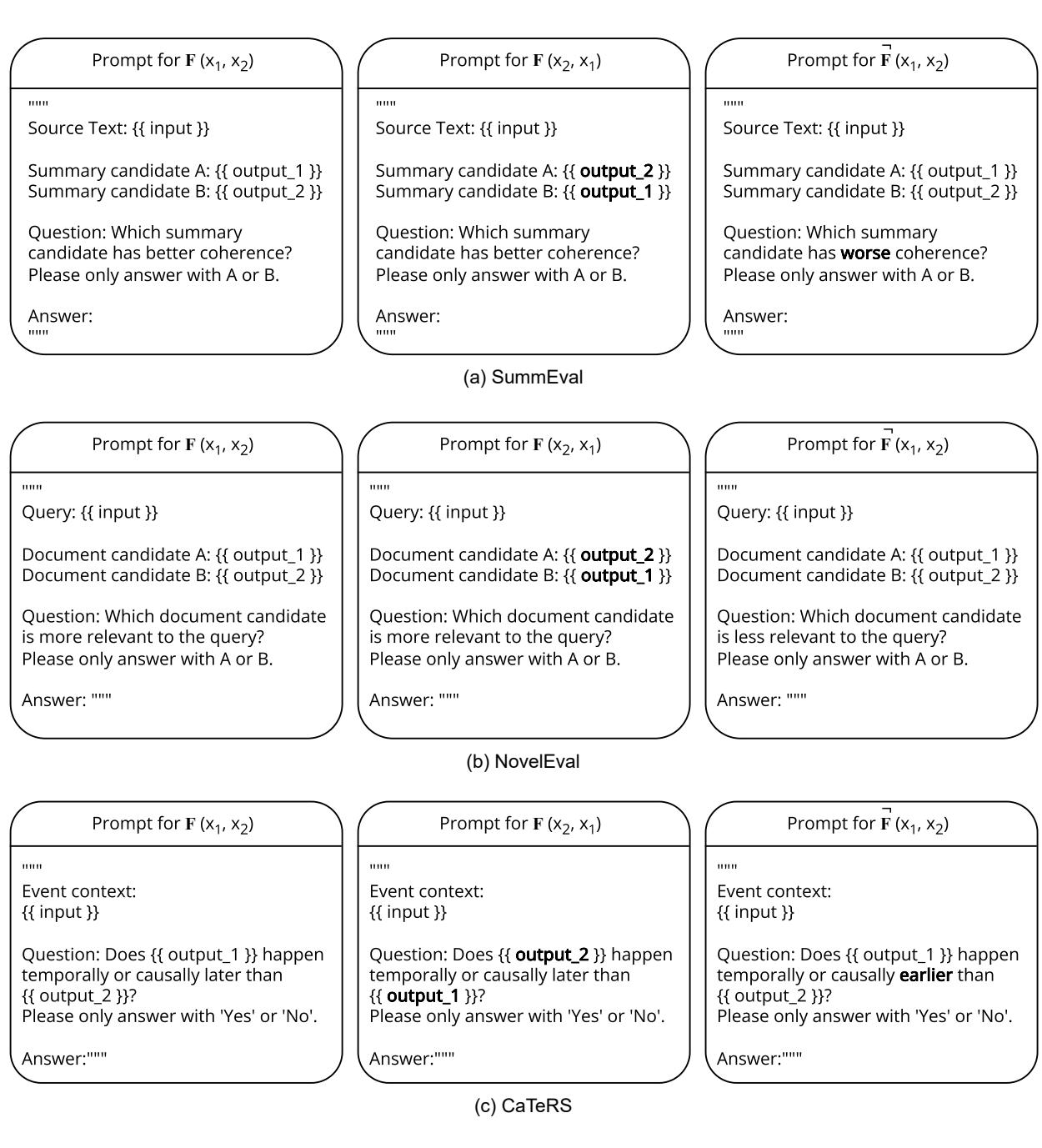

The results, summarized in Table 1, reveal some fascinating patterns.

Key Takeaways from the Diagnosis:

- Newer is (mostly) better: Newer models like Phi-3-medium and Gemma-2-9B show significantly higher consistency than older models like Llama-2.

- Transitivity is hard: While some models score high (90%+), others struggle to maintain a coherent worldview across multiple items.

- Subjectivity hurts logic: Models generally performed better on CaTeRS (temporal ordering) than SummEval. Why? Because time is objective. Event A physically happens before Event B. Summarization quality is subjective, leading the model to “waffle” more, creating inconsistencies.

- Chain-of-Thought (CoT) can backfire: This is a counter-intuitive finding. We usually assume CoT (asking the model to “think step by step”) improves everything. However, the researchers found that CoT sometimes decreased transitivity.

- Theory: When a model generates a long chain of thought, it introduces more tokens and potentially more “randomness” into its reasoning process. It might use slightly different logic for Pair A vs B than it does for Pair B vs C, leading to a cycle.

Consistency = Trustworthiness

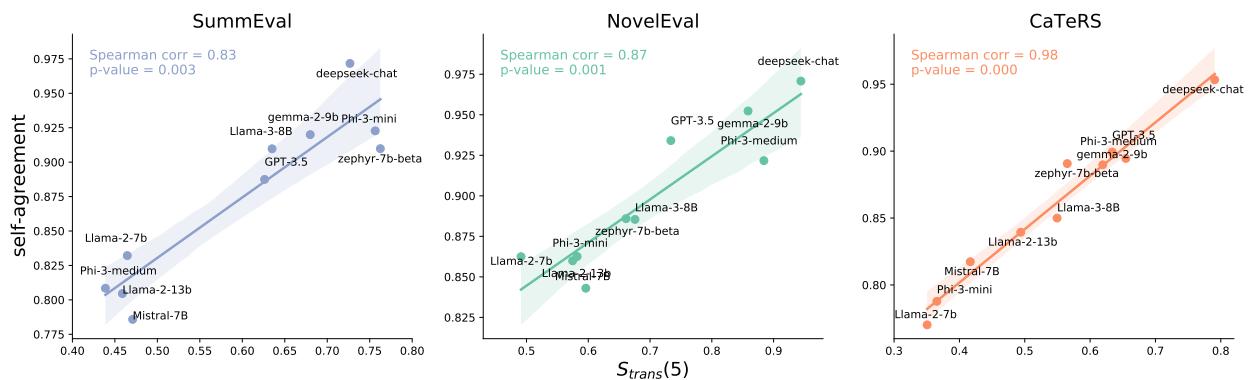

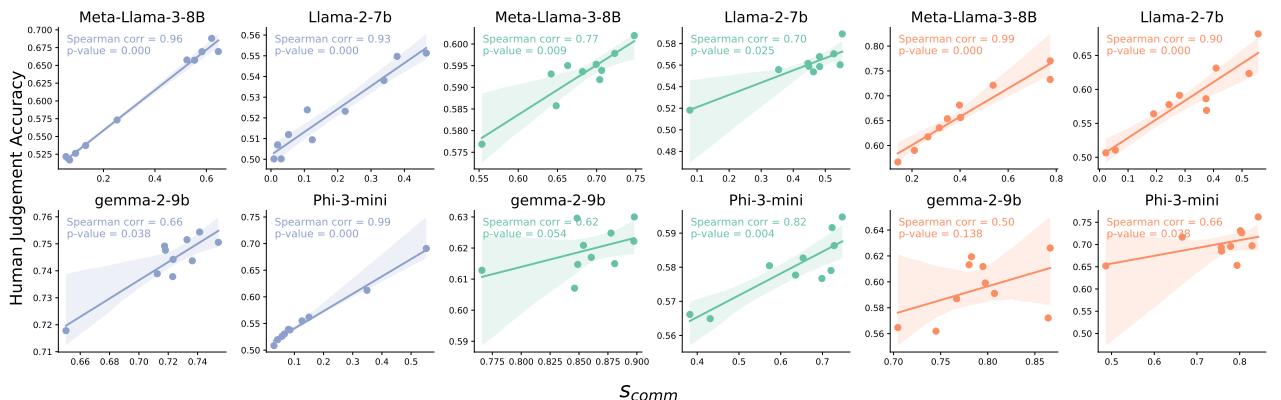

The researchers also found a strong correlation between a model’s logical consistency and its Self-Agreement (how often it gives the same answer if you ask the same question multiple times).

As shown in Figure 4, models with high transitivity (x-axis) are also models that don’t change their answers randomly (y-axis). This suggests that measuring logical consistency is a great proxy for measuring overall model reliability.

Furthermore, there is a strong link between Commutativity and Human Preference Accuracy. Models that are not swayed by the order of options tend to align better with human judgments.

Part 3: The Cure - REPAIR Framework

So, we have models that are logically flawed. How do we fix them?

You might think: “Just train them on more human data!”

The problem is that humans are inconsistent too. Human annotation datasets are full of noise, errors, and subjective contradictions. If you train an LLM on a dataset where annotator 1 says A>B and annotator 2 says B>A, the model learns confusion.

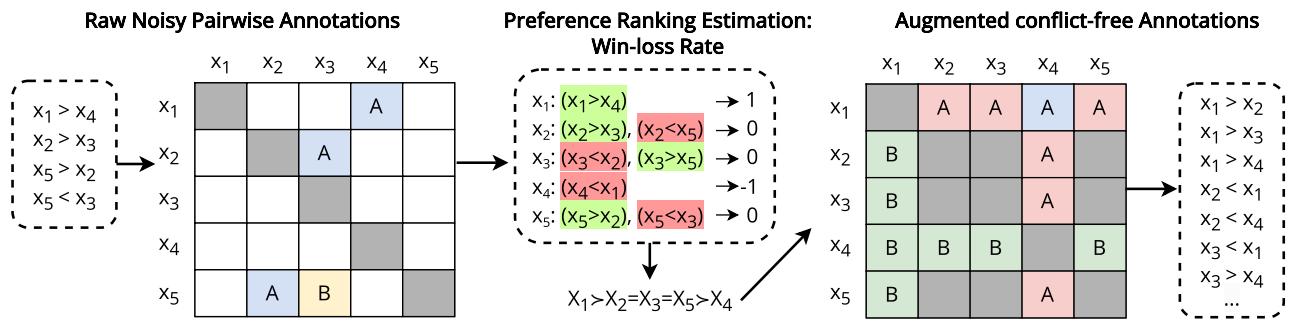

The researchers introduce REPAIR (Ranking Estimation and Preference Augmentation through Information Refinement).

The REPAIR Pipeline

The core idea is to take the noisy, contradictory pairwise data and “purify” it into a mathematically consistent ranking before showing it to the model.

Here is the step-by-step process illustrated in Figure 6:

- Input: Raw, noisy pairwise annotations (e.g., “A is better than B”, “B is better than C”, “C is better than A”).

- Estimation (Win-Loss Rate): The system looks at the global picture. It calculates a score for every item based on how many times it won comparisons across the whole dataset.

- If A beat B, A gets points.

- If C beat A, A loses points.

- Eventually, a global ranking emerges: \(X_1 = X_2 = X_3 = X_5 > X_4\).

- Linearization: The system forces the items into a ranked list based on these scores. This eliminates cycles. You can’t have a rock-paper-scissors loop in a numbered list.

- Augmentation: The system generates new pairwise comparisons based on this clean list. It implies relationships that weren’t in the original data. If the list says \(A > B > C\), the system creates a training example \(A > C\), even if a human never explicitly compared A and C.

- Instruction Tuning: The LLM is fine-tuned on this new, logically perfect dataset.

Why Win-Loss Rate?

The paper discusses different ways to rank items (like Elo ratings or the Bradley-Terry model). However, they chose the simple Win-Loss Rate. Why? Because it is robust to sparse data (where we don’t have comparisons for every pair) and doesn’t suffer as much from the order in which comparisons are processed.

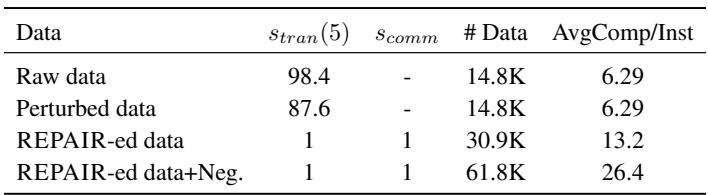

By augmenting the data, they also drastically increase the training set size, as seen in Table 2.

Part 4: Does REPAIR Work?

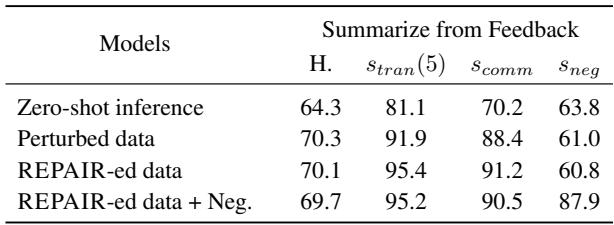

The researchers tested REPAIR by fine-tuning Llama-3-8B. They compared three versions:

- Zero-shot: The base model.

- Perturbed Data: Training on the raw, noisy data (simulating standard practice).

- REPAIR-ed Data: Training on the mathematically cleaned data.

The results were transformative.

Looking at Table 3, the REPAIR-ed models achieved near-perfect scores (1.0 or 100%) on transitivity and commutativity.

Crucially, Human Alignment (H.) did not drop. Often in AI, there is a trade-off: you can make a model more logical, but it becomes rigid and less “human-like.” Here, the models became perfectly logical while maintaining (and often slightly improving) their agreement with human preferences.

Note on Negation Invariance: To fix negation consistency (understanding “worse” vs “better”), the researchers had to explicitly include negated examples in the training data (the “REPAIR-ed data + Neg.” row). This boosted the negation score from 60.8% to 87.9%.

Impact on Real-World Algorithms

Finally, the researchers asked: “Does this actually help us sort things?”

They used an algorithm called PairS, which uses an LLM to sort a list of items (like a Bubble Sort or Merge Sort). Standard LLMs struggle here because if they are intransitive (\(A>B, B>C, C>A\)), the sorting algorithm runs in circles or produces the wrong order.

Table 4 demonstrates that models with higher transitivity (like the REPAIR-ed models) perform significantly better at sorting tasks.

An interesting finding here involves calibration. Usually, engineers have to run “calibration” passes (asking the model twice, swapping the order A-B then B-A) to average out bias. This doubles the cost and time of inference. The results show that highly commutative models (those fixed by REPAIR) don’t need this calibration. They get the right answer the first time, making them twice as efficient.

Conclusion

The “black box” nature of Large Language Models often gives them a free pass on logic. We are impressed by their prose and overlook their reasoning flaws. But as we move from using LLMs as chatbots to using them as decision-making agents, logical consistency becomes non-negotiable.

This paper provides a roadmap for that transition. It teaches us three key lessons:

- Measurement is feasible: We can mathematically quantify how “confused” a model is using Transitivity, Commutativity, and Negation Invariance.

- Human data is the bottleneck: Training directly on noisy human feedback teaches models to be inconsistent.

- Logic can be induced: By refining data through ranking algorithms like REPAIR, we can create training sets that force models to adhere to the laws of logic without sacrificing their alignment with human intent.

The future of reliable AI isn’t just about bigger models; it’s about models that don’t contradict themselves. With frameworks like REPAIR, we are one step closer to AI that logic—not just language—can rely on.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2410.02205/images/cover.png)