In the rapidly evolving landscape of Artificial Intelligence, a new arms race has begun. On one side, we have Large Language Model (LLM) providers like OpenAI and Google, who are striving to watermark their generated content. Their goal is noble: to label AI-generated text invisibly, helping to curb misinformation, academic dishonesty, and spam.

On the other side are the adversaries—users who want to strip these watermarks away to pass off AI text as human-written.

Until recently, the assumption was that watermarks were relatively safe as long as the “key” used to generate them remained secret. However, a new research paper titled “Optimizing Adaptive Attacks against Watermarks for Language Models” challenges this assumption. The researchers demonstrate that if an attacker simply knows the method being used (even without the secret key), they can train a smaller, cheaper AI model to strip the watermark almost perfectly, costing less than $10 in compute time.

In this post, we will deconstruct this paper, exploring how watermarking works, why current defenses are failing, and the clever optimization technique that allows a small 7-billion parameter model to outsmart a massive 70-billion parameter giant.

The Problem: Security Through Obscurity?

To understand the attack, we first need to understand the defense. LLM watermarking generally works by subtly biasing the word choices a model makes.

When an LLM generates text, it predicts the next word based on probability. A watermarking algorithm partitions the vocabulary into a “Green List” (allowed words) and a “Red List” (forbidden words) based on the previous tokens. By forcing the model to pick from the Green List more often than random chance would dictate, a statistical signal is embedded in the text. To a human, the text reads normally. To a detection algorithm with the correct key, the pattern shines like a beacon.

The Robustness Gap

A watermark is considered robust if removing it requires significantly damaging the quality of the text. If I have to turn a beautiful essay into gibberish to remove the watermark, the watermark wins.

However, the authors of this paper argue that current robustness testing is flawed. Most researchers test their watermarks against non-adaptive attackers—adversaries who simply try random strategies like:

- Swapping words with synonyms.

- Translating text to French and back.

- Adding typos or misspellings.

These are “blind” attacks. But what happens if the attacker is adaptive? What if they know how the watermarking algorithm works (e.g., they know it’s the “Dist-Shift” method or the “Exp” method) but just lack the private key?

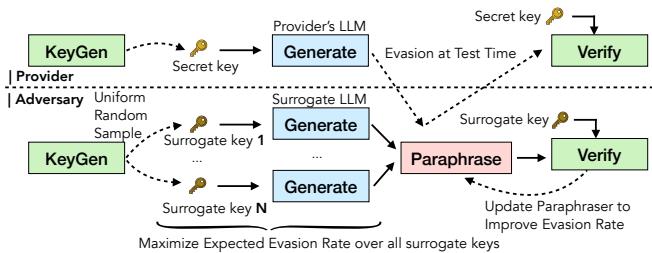

As shown in Figure 1, the adaptive attacker scenario involves a loop. The adversary uses a Surrogate LLM (a model they own) to simulate the provider’s watermarking process. By generating their own keys and practicing against this surrogate, they can train a “Paraphraser” model specifically designed to break the watermark.

The Core Method: Weaponizing Optimization

The researchers propose a method to train a specific type of neural network called a Paraphraser. The goal of this model is simple: take watermarked text as input and output clean text that (1) no longer triggers the detector and (2) maintains high linguistic quality.

Formulating the Objective

The researchers treat robustness as an optimization problem. They want to maximize an objective function that balances evasion and quality.

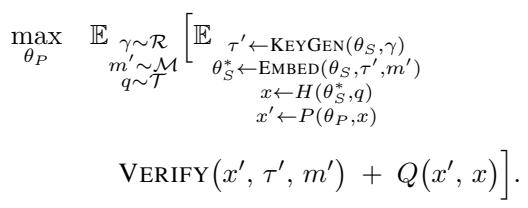

The mathematical formulation is presented below:

Let’s break this down:

- \(\theta_P\): The parameters of the attacker’s Paraphraser model (what we are training).

- \(\tau'\): A “surrogate key.” The attacker generates this using the known

KeyGenalgorithm. - VERIFY: The detection function. The attacker wants the output of this to be low (below the detection threshold).

- \(Q(x', x)\): The quality function. The attacker wants the paraphrased text \(x'\) to be very similar in meaning and quality to the original text \(x\).

The genius of this approach is the use of Surrogate Keys. The attacker doesn’t need the provider’s secret key (let’s call it \(\tau\)). Because the watermarking algorithm is public, the attacker can generate thousands of random keys (\(\tau'\)), watermark their own text, and train the Paraphraser to break those watermarks. The hypothesis is that a model capable of breaking a watermark generated with Key A, Key B, and Key C will learn the fundamental statistical weaknesses of the algorithm itself, allowing it to break the watermark generated by the provider’s secret Key X.

Creating the “Perfect” Attacker with Preference Optimization

Training an LLM to “maximize evasion” is difficult because text is discrete (you can’t easily differentiate through the selection of a specific word). To solve this, the authors use a technique similar to Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), specifically relying on preference datasets.

They curate a dataset of “winners” and “losers” to teach the model. Here is the process, detailed in Algorithm 1 of the paper:

- Generate: Use a surrogate model (e.g., Llama-2) to generate text with a specific watermark.

- Paraphrase: Use the current Paraphraser to generate \(N\) different variations of that text.

- Test: Check these variations against the surrogate key.

- Positive Sample: A paraphrase that successfully evades detection and has high quality.

- Negative Sample: A paraphrase that fails to evade detection.

- Train: Feed these pairs into the model, teaching it to prefer the “Positive” strategies.

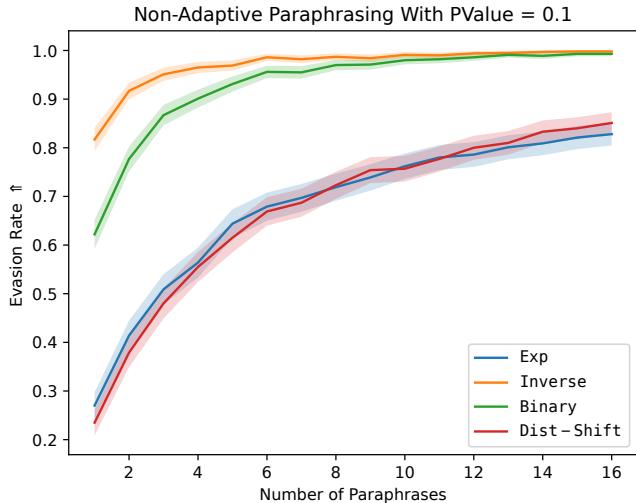

Figure 2 illustrates why this works. The graph shows the “Best-of-N” evasion rate. Even with a standard, untrained Llama-2 model, if you generate 16 paraphrases, there is a very high probability (~97% for some methods) that at least one of them will break the watermark. The training process essentially teaches the model to produce that “one lucky break” consistently on the first try.

Experiments: David vs. Goliath

The experimental setup pits a constrained attacker against a powerful defender.

- The Victim (Provider): A massive Llama-3-70B model.

- The Attacker: A much smaller Llama-2-7b or Qwen-2.5-7b model (roughly 10x smaller).

- The Cost: The authors note that curating the dataset and fine-tuning the attacker costs less than 7 GPU hours, or roughly $10 USD.

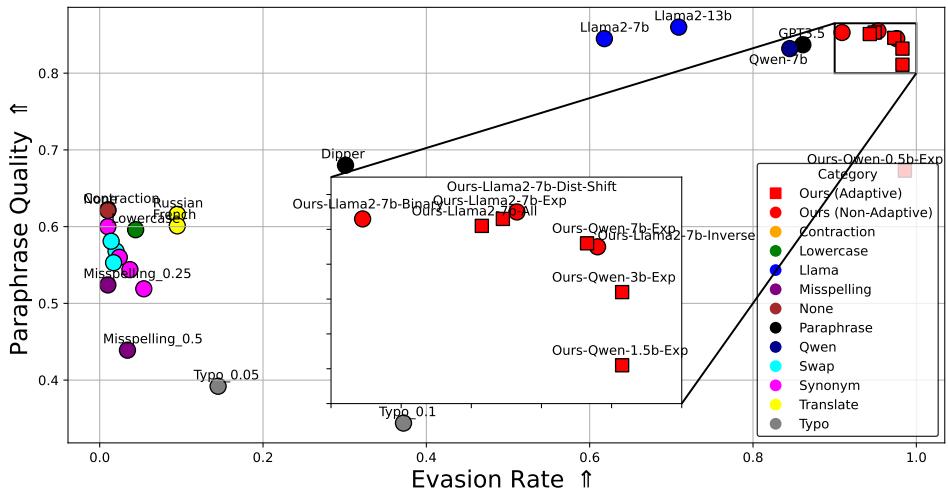

The Pareto Frontier

In security research, we look for the Pareto Frontier—the curve that represents the optimal trade-off between two conflicting goals. In this case, the goals are Text Quality vs. Evasion Rate.

A perfect attack would be in the top-right corner: 100% evasion with 100% quality retention.

Figure 4 reveals the stunning effectiveness of the adaptive attack.

- Circles (\(\circ\)): These are non-adaptive baselines (simple paraphrasing, synonym swapping). They are scattered in the middle—either they fail to evade (low X-axis) or they destroy the text quality (low Y-axis).

- Squares (\(\square\)): These are the adaptive attacks proposed in this paper. Notice how they push heavily toward the top right.

- Red Squares: These are the authors’ specific models (“Ours”). They achieve roughly 97% evasion while maintaining quality scores nearly identical to the original text.

Most notably, the attacker model (7B parameters) is significantly smaller than the victim model (70B), yet it completely neutralizes the security mechanism.

Transferability: The “Master Key” Effect

A critical question remains: If I train my attacker to break the “Dist-Shift” watermark, can it also break the “Exp” watermark? Or do I need to retrain for every new algorithm?

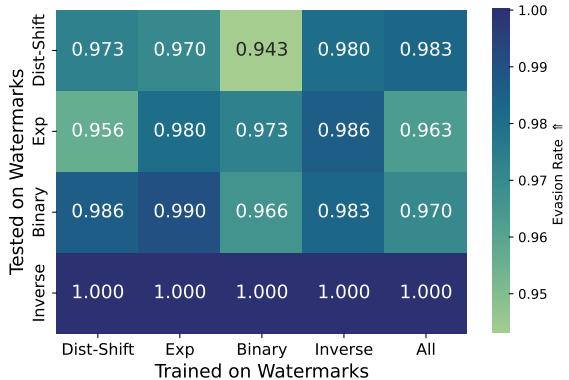

The researchers tested this by training on one watermark method and testing on others.

The heatmap in Figure 3 shows the results. The diagonal represents the adaptive setting (Train on X, Test on X), where evasion rates are nearly 100% (green/yellow). However, look at the off-diagonal elements. Even when the model is trained on “Dist-Shift” and tested on “Inverse” (bottom left), the evasion rate is still remarkably high.

This implies that watermarking methods share underlying statistical vulnerabilities. An attacker trained to smooth out the statistical anomalies of one method learns to smooth them out for all methods.

Qualitative Analysis: Does the text still make sense?

High evasion rates are useless if the output reads like a broken typewriter. The authors utilized “LLM-as-a-Judge” (using GPT-4 or Llama-3 to grade text) to ensure quality remained high.

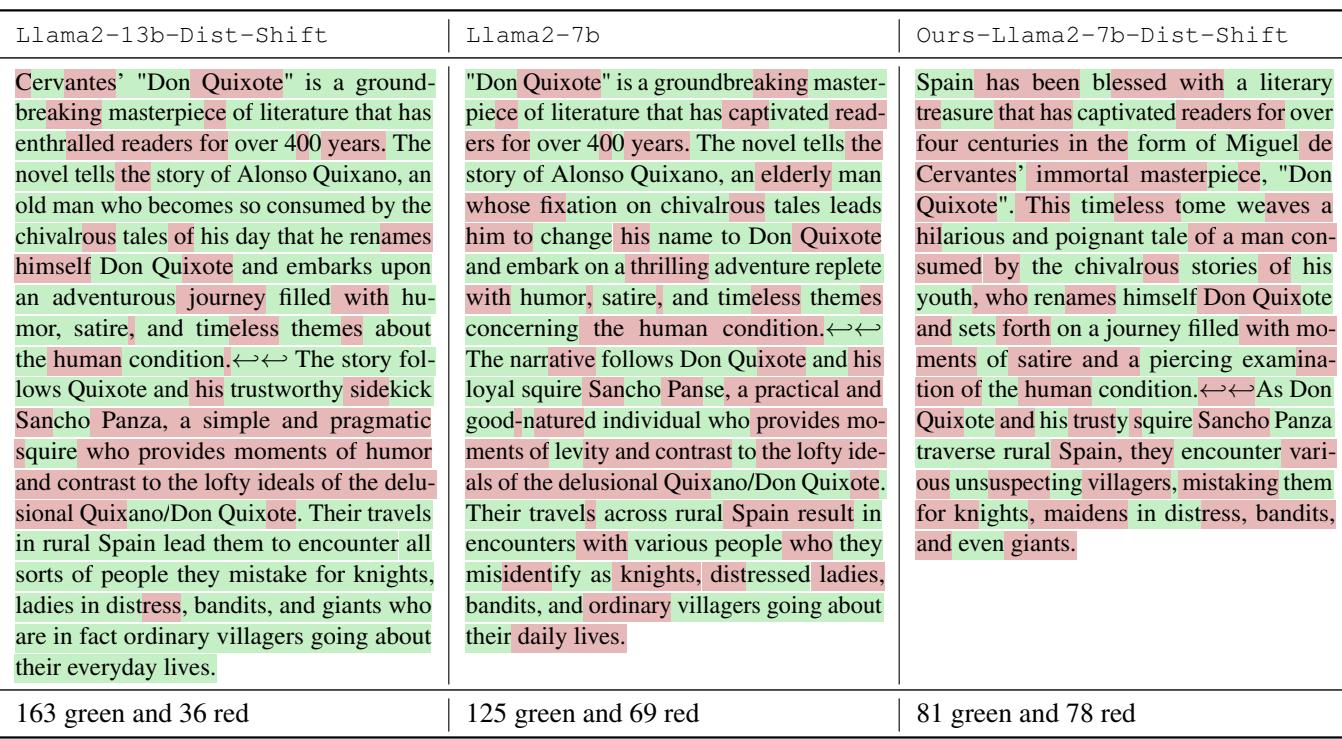

Table 2 provides a concrete example.

- Left (Watermarked): A text about “Don Quixote.” It has 163 “green” tokens and 36 “red” tokens. This ratio is statistically improbable, flagging it as AI.

- Right (Adaptive Attack): The meaning is identical. The flow is natural. But look at the ratio: 81 green, 78 red. This is a nearly perfect 50/50 split, which is exactly what human writing looks like to a detector. The watermark has been scrubbed clean.

What is the model actually doing?

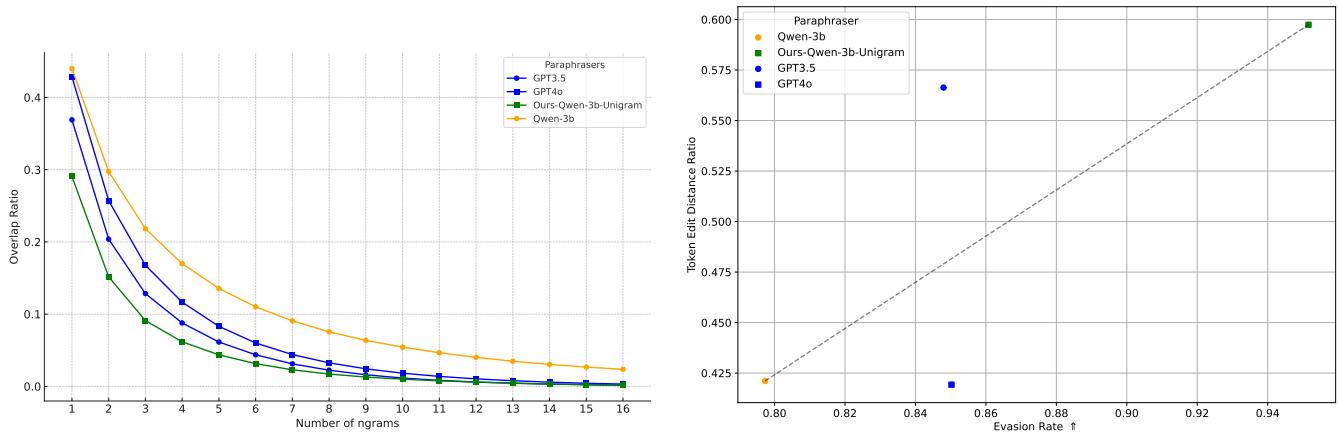

To understand how the model achieves this, the researchers analyzed the “Token Edit Distance” (how much the text changed) and the “N-gram Overlap” (how many phrases stayed the same).

Figure 15 offers a fascinating insight.

- Left Graph: The adaptive paraphraser (Ours-Qwen-3b) has a lower N-gram overlap than standard paraphrasers like GPT-3.5 or GPT-4. It changes the specific phrasing more aggressively.

- Right Graph: There is a direct correlation between the edit distance and the evasion rate. The adaptive model learns exactly how much it needs to edit the text to drop the detection confidence below the threshold (\(p < 0.01\)) without making unnecessary changes that would hurt quality. It is performing a surgical removal of the watermark.

Conclusion and Implications

This research papers serves as a wake-up call for the AI safety community. The findings are stark:

- Current watermarks are fragile: They rely on the attacker being “dumb.” Against an attacker who understands the algorithm and has $10 to spare, they crumble.

- Size doesn’t matter: A small, open-source model can defeat the protections on the world’s largest proprietary models.

- Generalization is a risk: Training against one watermark grants the ability to break unseen watermarks, suggesting that the entire concept of statistical watermarking may have fundamental limitations.

The authors suggest that future watermarking research must move away from “security by obscurity.” Robustness testing should include adaptive attackers—models trained specifically to break the system—rather than just random perturbations. Just as we test software security by hiring red teams to actively hack the system, we must test LLM watermarks by actively trying to erase them with AI.

Until then, we must accept that any watermark currently deployed can likely be washed away with a simple, optimized paraphrase.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2410.02440/images/cover.png)