Language models (LMs) like GPT-4 or Llama have revolutionized natural language processing, but they have also become indispensable tools for a completely different field: Computational Psycholinguistics.

Researchers use these models to test theories about how the human brain processes language. The dominant theory in this space is Surprisal Theory, which posits that the difficulty of processing a word is proportional to how “surprised” the brain is to see it. If a language model assigns a low probability to a word, it has high surprisal, and—theory holds—a human will take longer to read it.

But there is a massive, often overlooked technical flaw in this comparison. Modern Language Models do not read like humans do. Humans read characters that form words and phrases. Language models read tokens—arbitrary chunks of sub-word units (like “ing,” “at,” or “sh”) created by algorithms like Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE).

This creates a mismatch. When a psycholinguist wants to know the surprisal of a specific word or region of text, they are often fighting against the model’s arbitrary tokenization.

In the paper Marginalizing Out Tokenization in Surprisal-Based Psycholinguistic Predictive Modeling, researchers Mario Giulianelli and colleagues argue that we have been doing it wrong. They propose a rigorous method to bridge the gap between token-based models and character-based human reading. By “marginalizing out” the tokenizer, they unlock new ways to predict reading behavior, discovering that the most predictive parts of a word might not be the whole word at all, but rather specific “Focal Areas.”

In this post, we will tear down the barrier between tokenizers and cognitive science, explore the math behind character-level prediction, and look at experimental results that reshape our understanding of how we read.

The Conflict: Human vs. Machine “Reading”

To understand the problem, we first need to look at how psycholinguistic experiments are designed.

In a typical eye-tracking study, a participant sits in front of a screen reading sentences while a camera records exactly where they look and for how long. The text is divided into Regions of Interest (ROIs). Usually, an ROI corresponds to a word.

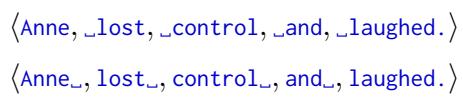

Consider the sentence: “Anne lost control and laughed.”

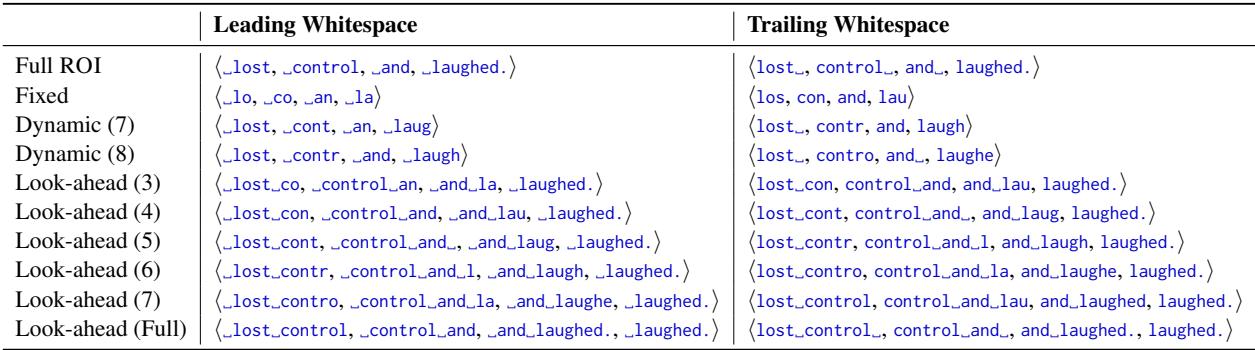

As shown in the image above, a researcher might define the ROIs in different ways. They might include the whitespace before the word (Leading) or after the word (Trailing).

- Leading Whitespace:

_lost,_control - Trailing Whitespace:

lost_,control_

This distinction seems trivial to a human. To a Language Model, it is a headache.

Standard LMs process text as a sequence of tokens from a fixed vocabulary. The mapping from text to tokens is deterministic but often counter-intuitive. For example, depending on the tokenizer, the word control might be a single token, but _control (with a space) might be broken into _ and control, or _con and trol.

This leads to a methodological crisis. If you want to calculate the surprisal (difficulty) of the word “control,” which tokens do you sum up? Do you include the whitespace token? What if the tokenizer splits the word in a way that doesn’t align with your ROI?

Recent studies have argued back and forth about whether to include trailing or leading whitespaces to get the best fit for human reading times. Giulianelli et al. argue that this debate misses the point. The specific tokenization scheme is an implementation detail of the model, not a property of the language or the human brain.

The Solution: A Character-Level Perspective

The authors propose a radical simplification: Tokenization is irrelevant.

Or rather, it should be. We should view language models as probability distributions over strings of characters, not tokens. Even if the model uses tokens internally, we can mathematically convert its output into character-level probabilities.

Defining Surprisal

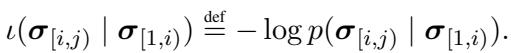

First, let’s formalize the core metric. Surprisal is the negative log probability of a string. If we have a sequence of characters, the surprisal of a specific region (like a word) given the context (the previous words) is defined as:

Here, \(\sigma_{[i, j)}\) represents the characters in our Region of Interest (ROI), and \(\sigma_{[1, i)}\) is the context history.

The challenge is that LMs give us \(p(\text{tokens})\), not \(p(\text{characters})\). To bridge this gap, the authors utilize a technique called Marginalization.

Marginalizing the Tokenizer

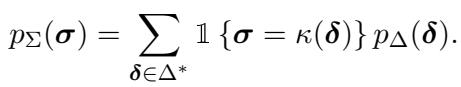

This is the mathematical heart of the paper. Since a single string of characters could theoretically be represented by multiple different sequences of tokens (a phenomenon known as “spurious ambiguity”), we need to sum up the probabilities of all possible token sequences that result in our target character string.

Ideally, a tokenizer like BPE is deterministic—one string equals one token sequence. However, to treat the model as a true character-level model, we must acknowledge that the model assigns probability mass to any valid sequence of tokens.

The probability of a character string \(\sigma\) is the sum of the probabilities of all token sequences \(\delta\) that decode into \(\sigma\):

By performing this summation (or an approximation of it using a “beam summing” algorithm to handle the computational complexity), we convert a token-level GPT-2 into a character-level predictor.

Why does this matter? Because it frees us.

Once we have a character-level model, we are no longer restricted to calculating the surprisal of “tokens.” We can calculate the surprisal of any substring we want. We are no longer forced to ask, “What is the surprisal of this BPE token?” We can ask, “What is the surprisal of these specific 3 letters?”

This freedom allows the authors to introduce a new concept: Focal Areas.

Focal Areas: Zooming in on Reading Behavior

If we assume the brain is a prediction engine, what exactly is it predicting? Is it predicting the next whole word? The next morpheme? The next letter?

Eye-tracking research tells us that human vision is complex. When we fixate on a word, our peripheral vision (the “parafovea”) picks up information about the next word. We might see the first few letters of the upcoming word before we even move our eyes to it.

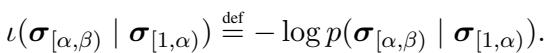

Therefore, the difficulty of processing a word might depend on the surprisal of just its first few characters, rather than the whole word. The authors define a Focal Area as a specific substring within or overlapping an ROI.

Using their character-level math, the researchers defined several types of Focal Areas to test against human data:

- Full ROI: The standard approach. The whole word.

- Fixed-size: Just the first 3 characters of the word (e.g., “con” for “control”).

- Dynamic: The first \(N\) characters, where \(N\) changes based on the length of the previous word and how far the eye can see (word identification span).

- Look-ahead: Including the current word plus characters from the next word.

The table below illustrates exactly how these focal areas differ for the sentence “Anne lost control…”

Look closely at the “Fixed” row. For the ROI “_control”, the focal area is just _co. The hypothesis is that the brain decides to skip or process the word based largely on these initial characters.

Experimental Setup

To test which of these Focal Areas best predicts human reading behavior, the authors used four major eye-tracking datasets: UCL, Provo, MECO, and CELER.

They measured two things:

- Skip Rate: How often a reader skips a word entirely.

- Reading Duration: How long the eye fixates on a region (First Fixation, Gaze Duration, Total Duration).

They trained a regression model to predict these human metrics using the surprisal values calculated from the different Focal Areas. The metric for success was \(\Delta R^2\)—essentially, how much better the model predicts human behavior when adding the surprisal feature compared to a baseline model that only knows word length and frequency.

Key Results

The findings challenge the standard practice of just using “word surprisal.”

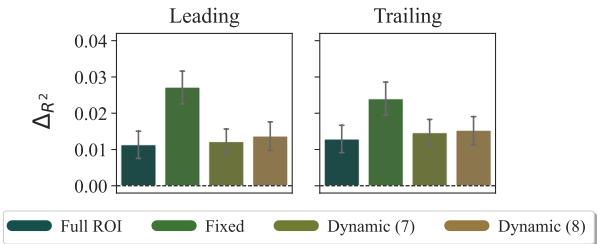

1. Predicting Skip Rates

When do we skip a word? The results suggest we decide to skip based on the start of the word.

In the graph above (from the CELER dataset), look at the green bars representing the Fixed focal area (the first 3 characters). It has the highest predictive power (\(\Delta R^2\)), significantly outperforming the “Full ROI” (dark teal).

Interpretation: This aligns with the “parafoveal preview” benefit. As you are finishing the previous word, your eye catches the first few letters of the next word (_co). If _co is highly predictable in that context, your brain says, “I know this word, no need to look at it directly,” and you skip it. Calculating surprisal on the whole word _control adds noise because your brain made the decision before processing the end of the word.

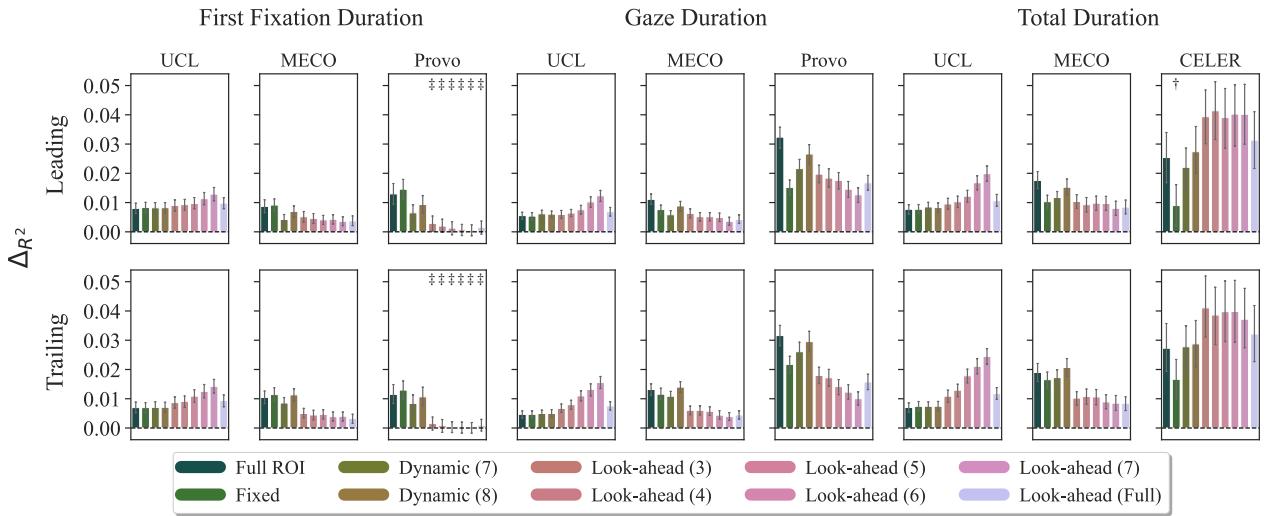

2. Predicting Reading Duration

When we do stop to read a word, what predicts how long we stay?

Here, the story changes. The Look-ahead focal areas often perform best.

In the UCL dataset (top left of the image), notice the purple bars representing Look-ahead. These focal areas include the current word plus the beginning of the next word.

Interpretation: This suggests that the time we spend on a word is influenced by the “processing cost” of integrating the current word and preprocessing the next one. We don’t read in isolated buckets; our processing spills over. A model that looks ahead captures this cognitive reality better than a model that stops at the word boundary.

3. The Whitespace Debate

Recall the earlier mention of the debate between “Leading” vs. “Trailing” whitespace (e.g., _word vs word_).

The results (visible in Figures 1 and 2) show that while there are slight differences, the Focal Area method works for both. By marginalizing out the tokenization, the researchers decoupled the definition of the ROI from the artifacts of the tokenizer. Whether you attach the space to the front or back matters less than whether you are measuring the surprisal of the correct cognitive unit (e.g., the first 3 chars vs the whole string).

Conclusion: Algorithm vs. Theory

This paper is a significant step forward for computational psycholinguistics because it cleans up a messy methodology.

For years, researchers have been forced to hack around tokenizers, debating whether to add spaces or how to handle split words. This paper argues that tokenization is an engineering convenience, not a cognitive reality.

By mathematically marginalizing out the tokens, we can treat Large Language Models as character-level probability engines. This flexibility allows us to ask more precise questions about reading.

The discovery that Fixed-size (first 3 chars) focal areas predict word skipping better than full words is a strong validation of this approach. It suggests that future models of reading should focus less on “words” as atomic units and more on the stream of visual information—the characters—that the brain actually processes.

Takeaways for Students:

- Don’t trust the tokenizer: Just because GPT-4 sees “ing” as a token doesn’t mean the human brain processes it as a discrete unit in the same way.

- Marginalization is powerful: It allows you to transform a model’s output distribution into a format that fits your scientific questions, rather than forcing your questions to fit the model.

- The Eye is faster than the Mind: We process upcoming text before we look at it. Predictive models need to account for this look-ahead (parafoveal) mechanism.

The tools we use to study the mind—like Language Models—are imperfect proxies. Work like this helps us sharpen those tools, ensuring that we are measuring human cognition, not just tokenizer artifacts.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2410.02691/images/cover.png)