Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 have rapidly transitioned from novelties to essential productivity tools. We use them to draft emails, summarize meetings, and debug code. The prevailing narrative is that these models act as “co-pilots,” boosting efficiency while the human remains the pilot in command.

But what happens when the task isn’t just about speed, but about expert judgment in a specialized field? When an expert relies on an LLM for complex analysis, are they truly using the tool, or is the tool subtly influencing their perception of reality?

A recent paper titled “The LLM Effect: Are Humans Truly Using LLMs, or Are They Being Influenced By Them Instead?” by researchers at George Mason University tackles this question head-on. By designing a rigorous study involving policy experts and “AI Policies in India,” the authors uncover a fascinating—and slightly worrying—trade-off between workflow speed and analytical independence.

In this deep dive, we will explore how LLMs introduce “anchoring bias,” why they struggle with nuance, and what the data says about the true cost of AI efficiency.

The Core Problem: Efficiency vs. Bias

The motivation behind this research is straightforward. LLMs are increasingly being deployed in domains that require high expertise, such as legal analysis, medical diagnostics, and policy studies. These fields usually rely on “Topic Modeling”—identifying latent themes within massive sets of documents.

Traditionally, this is a slow, labor-intensive process performed by humans. LLMs promise to automate this, or at least speed it up significantly. However, the researchers hypothesized that introducing an LLM into this workflow might trigger anchoring bias.

Anchoring bias is a cognitive phenomenon first described by Tversky and Kahneman in 1974. It occurs when an individual relies too heavily on an initial piece of information (the “anchor”) when making decisions. If an LLM suggests a set of topics or labels first, the human expert might unconsciously anchor their own analysis to those suggestions, potentially overlooking unique or subtle insights that the AI missed.

To test this, the researchers set up a two-stage experiment to measure both the efficiency gains and the cognitive influence of LLMs.

Study Design: A Tale of Two Groups

The study focused on a specific, complex domain: analyzing interviews regarding the evolution of AI policy in India. This content is dense, nuanced, and requires domain expertise to interpret correctly—a perfect test bed for human-AI collaboration.

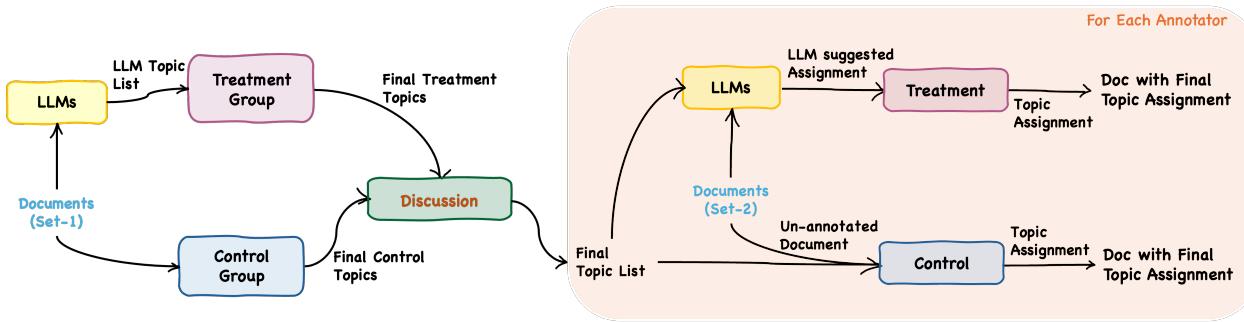

The researchers recruited four policy experts and divided the study into two distinct stages:

- Topic Discovery: Reading documents to create a list of relevant topics.

- Topic Assignment: Labeling specific paragraphs in new documents using that list.

Crucially, the experts were split into two settings:

- Control Setting: Experts worked alone, relying solely on their judgment.

- Treatment Setting: Experts were provided with LLM-generated suggestions (topics or labels) to guide them.

The researchers used a “Think Aloud” protocol, where experts had to vocalize their thought process as they worked. This qualitative data, combined with quantitative logs, provided a window into how the AI was influencing their decisions.

As shown in Figure 1 above, the study was designed to compare the outputs of the “human-only” workflow against the “human-plus-AI” workflow at every step.

Stage 1: Topic Discovery and the “Nuance Gap”

In the first stage, the goal was to identify what topics actually existed in the interview transcripts. The Control group read the text and generated topics from scratch. The Treatment group received a list of topics generated by GPT-4 and used them as a starting point.

The results of this stage highlighted a critical limitation of current LLMs: the lack of nuance.

The Consensus Process

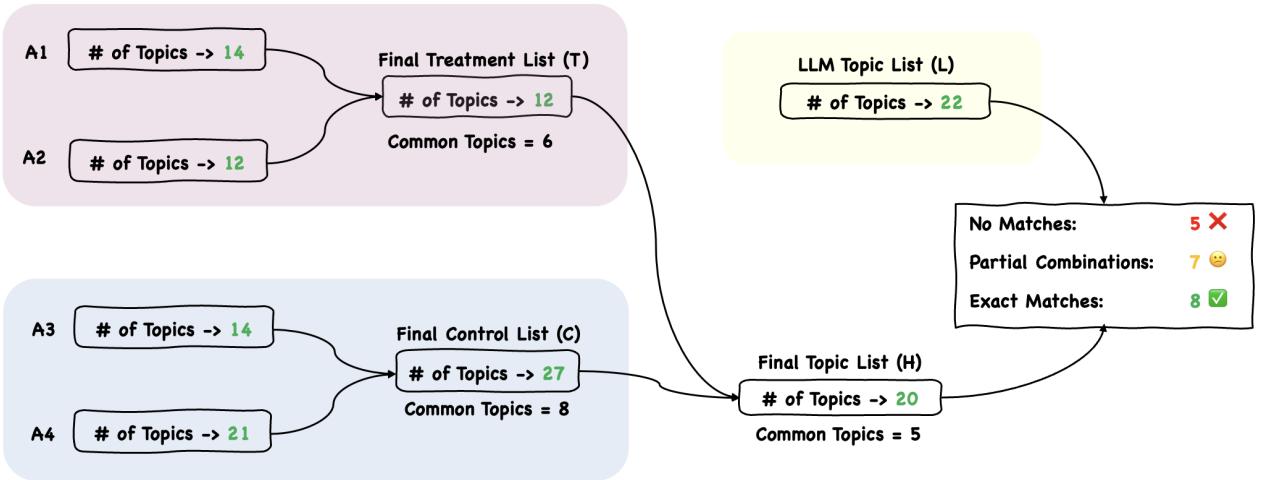

After working individually, the human annotators came together to merge their lists and create a “Final Topic List” (H). They compared the Control list (C), the Treatment list (T), and the raw LLM list (L).

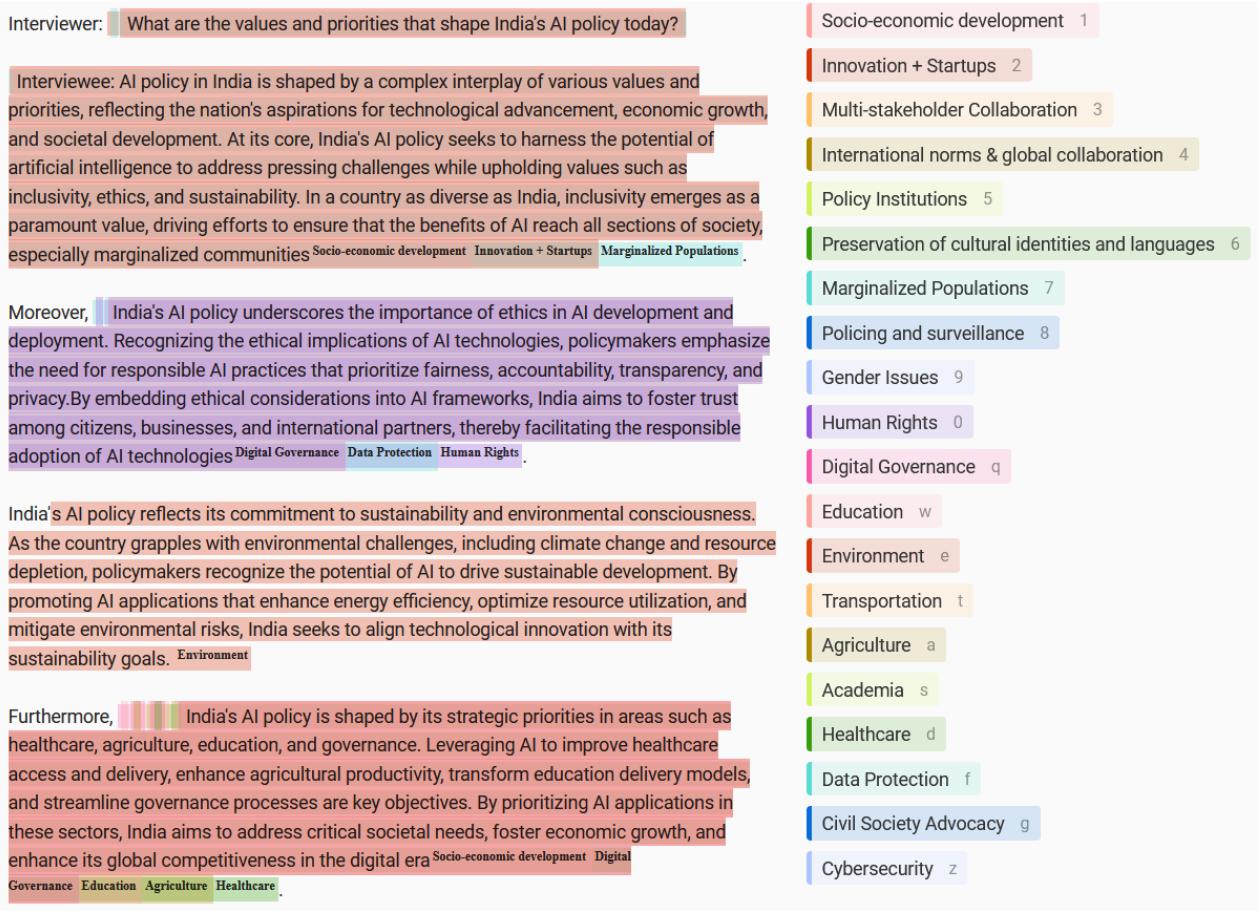

Figure 2 illustrates this integration. While there was significant overlap, the experts found that the LLM often provided generalized, broad labels. For instance, the LLM might suggest “Gender Studies,” whereas the humans preferred “Gender Issues” to capture specific inequalities mentioned in the text.

What the LLM Missed

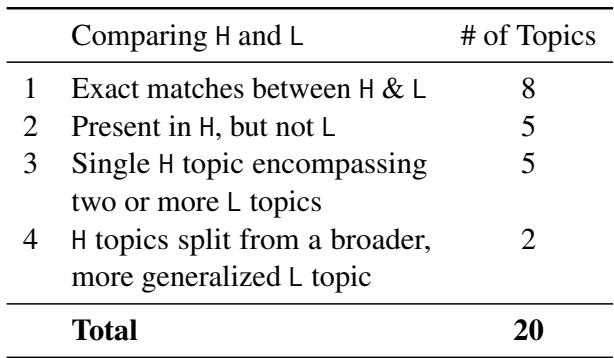

The most telling data point from Stage 1 was what the LLM failed to see entirely. The experts identified 20 core topics for the final list. The LLM successfully identified or overlapped with 15 of them. However, 5 topics were completely missed by the AI.

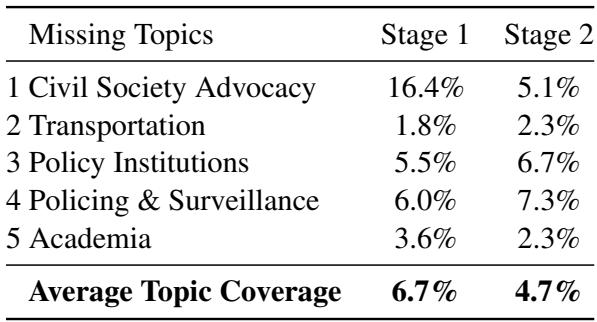

Table 1 summarizes this discrepancy. While missing 5 out of 20 might not seem catastrophic, the nature of these missing topics is vital. The missing topics included specific, sensitive areas like “Policing & Surveillance” and “Civil Society Advocacy.”

Why did the LLM miss them? The researchers analyzed the frequency of these topics in the text.

Table 2 reveals the answer: these topics had low prevalence (coverage) in the documents. “Transportation” appeared in only 1.8% of the text; “Policing & Surveillance” in 6.0%.

This suggests a “majority vote” bias in the model. The LLM is excellent at summarizing the bulk of the conversation (broad, generalized topics) but fails to pick up on low-frequency but high-impact signals. In policy analysis, a brief mention of surveillance concerns might be the most politically significant part of an interview, yet the LLM smoothed it over.

Stage 2: Topic Assignment and Anchoring Bias

The second stage of the study involved applying the Final Topic List to new documents. This is where the trade-off between speed and bias became undeniably clear.

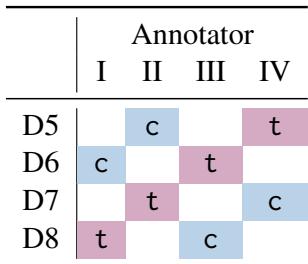

The researchers used a Latin Square design, meaning every expert acted as both a Control (on one document) and Treatment (on another document). This ensured that differences in performance were due to the AI assistance, not the individual expert’s skill.

The experts used a customized interface (Label Studio) to assign topics to paragraphs. The Treatment group saw pre-highlighted suggestions from the LLM, which they could accept, reject, or modify.

The Efficiency Explosion

First, the good news for AI advocates: the efficiency gains were massive.

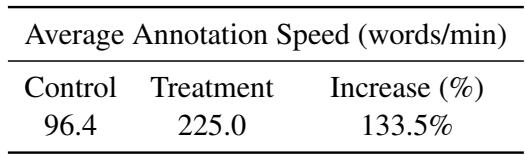

When working without AI (Control), experts annotated at an average speed of 96.4 words per minute. When assisted by the LLM (Treatment), that speed jumped to 225.0 words per minute.

As shown in Table 5, this is a 133.5% increase in speed. In a professional setting, this difference is transformative. It turns a week-long analysis project into a two-day task.

The Hidden Cost: Anchoring Bias

However, speed wasn’t the only thing that changed. The researchers analyzed the agreement levels between the humans and the LLM using Cohen’s Kappa (\(\kappa\)), a statistical measure of inter-annotator reliability.

The logic is as follows: If the humans are truly independent, their agreement with the LLM should be roughly the same whether they see the suggestions or not. If they agree with the LLM more simply because they saw the suggestions, that is evidence of bias.

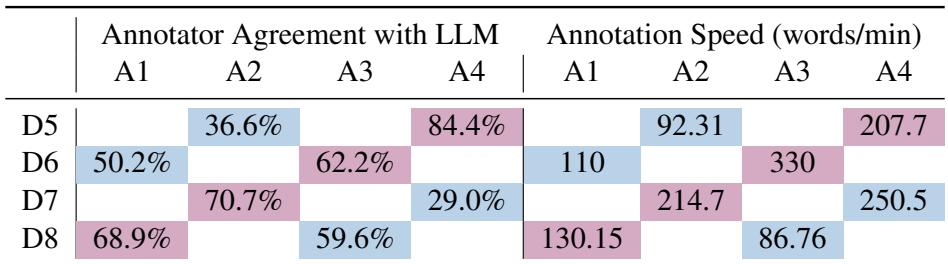

Table 6 presents the “smoking gun” of the study.

Look at the columns under “Annotator Agreement with LLM.”

- Control (Blue): When experts worked alone, their agreement with the LLM’s “ground truth” was relatively low (e.g., 36.6% for A2 on D5). This indicates that their independent expert judgment often differed from the AI’s logic.

- Treatment (Pink): When those same experts were shown the LLM suggestions, their agreement skyrocketed (e.g., 84.4% for A4 on D5).

The statistical analysis confirmed this was non-random (\(p < 0.001\)). The experts weren’t just faster; they were actively changing their decisions to align with the AI.

The “Think Aloud” transcripts supported this. In the Control setting, experts grappled with difficult decisions, debating whether a paragraph was about “Privacy” or “Surveillance.” In the Treatment group, experts often looked at the suggestion, found it “good enough,” and moved on. The friction of critical thinking was removed, replaced by the ease of verification.

Survey Results: Trust vs. Reality

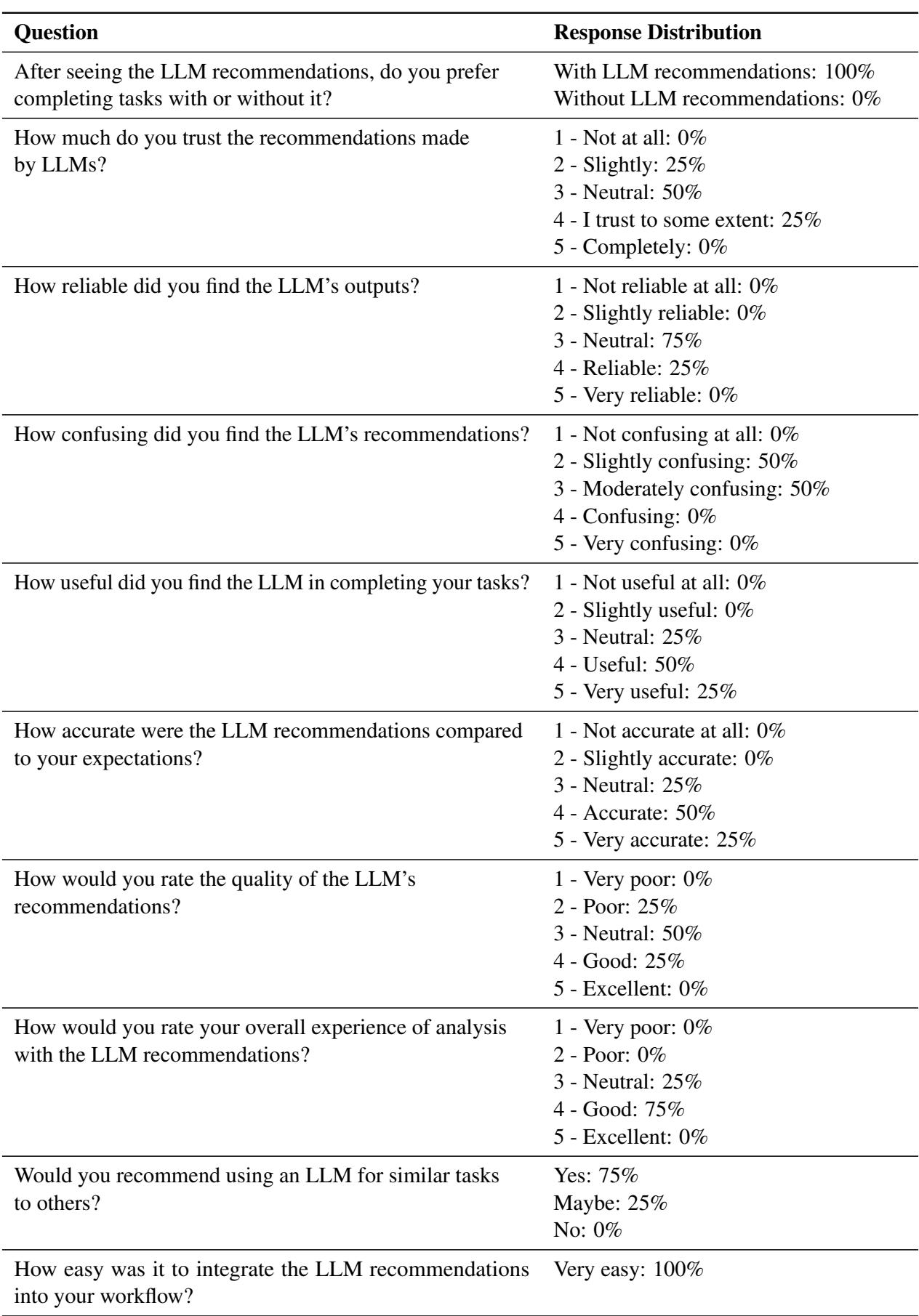

Finally, the researchers surveyed the experts before and after the study to gauge their perception of the technology.

Interestingly, despite the demonstrated bias and the missed topics in Stage 1, the experts came away with a very positive view of the collaboration.

As seen in the Post-Analysis survey (Table 8):

- 100% of participants preferred completing tasks with LLM recommendations.

- 100% found it “Very easy” to integrate into their workflow.

- Most rated the experience as “Good.”

This highlights a dangerous disconnect. The users felt more productive and satisfied, but they were unaware of how significantly their decision-making process had been altered or “anchored” by the machine. They perceived the tool as a helpful assistant, not realizing it was effectively steering the ship.

Conclusion: The Trade-Off

This paper provides crucial empirical evidence for a phenomenon many have suspected. The “LLM Effect” is real.

- Efficiency is undeniable: Using LLMs more than doubles the speed of expert analysis.

- Bias is inevitable: Showing an expert an answer before they think of it fundamentally changes their answer.

- Nuance is lost: LLMs smooth over rare but critical details (like “Policing & Surveillance”) in favor of broad, generalized themes.

The implications for students and professionals are significant. If you are using an LLM to summarize papers, analyze data, or write code, you are likely working much faster. But you are also likely converging on the “average” view represented by the model, potentially missing the specific, outlier insights that often matter most in high-level research.

The authors conclude that while we shouldn’t abandon these tools, we need to design better workflows—perhaps “human-first” systems where the expert establishes the framework before the AI fills in the gaps—to ensure we get the speed of the engine without losing the steering of the expert.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2410.04699/images/cover.png)