Imagine you are a resident doctor in a busy emergency room. You examine a patient, review their vitals, and turn to your attending physician with a diagnosis. “It’s pneumonia,” you say. The attending looks at you and asks the most terrifying question in medical education: “Why?”

It is not enough to get the answer right. In medicine, the reasoning process—the chain of evidence connecting symptoms to a diagnosis—is just as critical as the conclusion itself.

This “explainability gap” is currently one of the biggest hurdles in Artificial Intelligence. While Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 or Med-PaLM are passing medical licensing exams with flying colors, they often function as “black boxes.” They give us the answer, but they struggle to provide a structured, logical argument for why that answer is correct and, crucially, why other plausible options are wrong.

In this post, we are doing a deep dive into CasiMedicos-Arg, a new research paper that introduces a groundbreaking multilingual dataset designed to solve this problem. The researchers have created a resource that teaches AI not just to answer medical questions, but to argue for them using the same structural logic as a human doctor.

The Problem: Accuracy Without Explanation

There has been an explosion of interest in Medical Question Answering (QA). Benchmarks like MedQA and PubMedQA have driven the development of models that can achieve expert-level accuracy on multiple-choice questions.

However, existing research has two major shortcomings:

- Lack of Argumentation: Most datasets focus on selecting the correct option (A, B, C, or D). Very few include detailed natural language explanations, and almost none break those explanations down into structured arguments (claims, premises, support, and attacks).

- The Language Barrier: The vast majority of medical AI benchmarks are in English. This limits the ability to test and deploy these powerful tools in global healthcare settings where French, Spanish, or Italian are the primary languages.

The CasiMedicos-Arg paper addresses both issues head-on. It presents the first multilingual dataset (English, French, Italian, Spanish) where clinical cases are enriched with explanations that have been manually annotated to show how the doctor is thinking.

The Foundation: What is Explanatory Argumentation?

To understand the contribution of this paper, we first need to understand how the researchers define an “argument.” They didn’t just ask doctors to write paragraphs; they broke those paragraphs down into specific components based on argumentation theory.

When a doctor explains a case, they are essentially building a legal case for a specific disease. The researchers annotated the text using the following structure:

- Claim: A concluding statement. (e.g., “The patient presumably has erythema nodosum.”)

- Premise: Observed facts or evidence that support or attack a claim. (e.g., “The patient has a fever of 39°C.”)

- Relations:

- Support: A premise that proves a claim is true.

- Attack: A premise that proves a claim (or a wrong answer) is false.

This structure allows an AI to learn that symptom X supports diagnosis Y, while symptom Z attacks diagnosis W.

Building the Dataset: A Manual Effort

The researchers started with the CasiMedicos corpus, a collection of clinical cases from the Spanish Medical Resident Intern (MIR) exams. These cases are unique because they include gold-standard explanations written by volunteer medical doctors.

The team took 558 of these clinical cases and performed a rigorous manual annotation process. This wasn’t a simple keyword search; human annotators read the doctors’ explanations and labeled every sentence to identify the argumentation structure.

The Scope of the Data

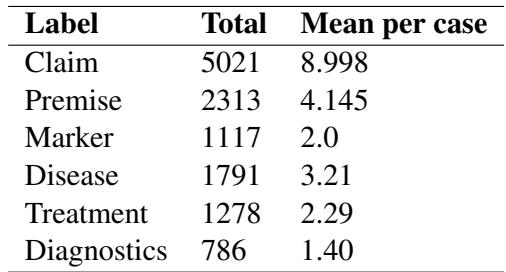

To give you an idea of the scale, let’s look at the distribution of labels across the cases.

As shown in Table 3, the dataset contains over 5,000 Claims and 2,300 Premises. You might notice something interesting in the table: the number of Claims is much higher than the number of Premises.

Why? In medical reasoning, doctors often make statements based on general medical knowledge (which counts as a Claim in this schema) rather than restating the specific facts of the patient’s case (Premises). For example, a doctor might say, “This disease usually affects women under 30” (Claim based on knowledge) to support their diagnosis, rather than explicitly repeating “The patient is a woman under 30” (Premise).

The Logic of Support and Attack

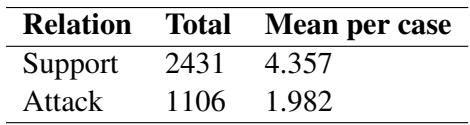

One of the most valuable aspects of this dataset is that it teaches AI how to rule things out, not just rule things in.

Table 5 illustrates the argumentative relations. While Support relations are the most common (2,431 instances), there is a significant number of Attack relations (1,106).

This is vital for medical safety. A reliable AI assistant shouldn’t just tell a doctor, “It’s the flu.” It should be able to say, “It is likely the flu because of the fever (Support), and we can rule out bacterial meningitis because the neck stiffness is absent (Attack).”

Ensuring Quality

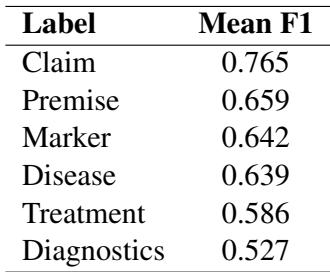

Annotating subjective explanations is difficult. To ensure the data was reliable, the researchers measured Inter-Annotator Agreement (IAA)—essentially, how often two different humans agreed on the labels.

Table 1 shows the agreement scores (F1) for the different components. A score of 0.765 for Claims is quite strong for this type of complex linguistic task, indicating that the definition of a “medical claim” is consistent and learnable.

Going Multilingual: The Projection Method

One of the paper’s standout features is its multilingual capabilities. The original explanations were in Spanish, translated to English, French, and Italian. However, manually annotating the argument structures for all four languages from scratch would have been prohibitively expensive and time-consuming.

The researchers used a clever technique called Label Projection.

- Source Annotation: They performed the heavy lifting (manual annotation of claims/premises) on the English version.

- Alignment: They used automated tools to align the words in the English text with their counterparts in Spanish, French, and Italian.

- Projection: The labels were automatically “projected” onto the other languages.

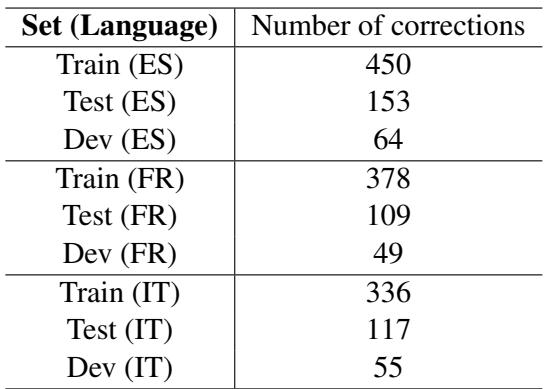

- Correction: Crucially, they didn’t trust the automation blindly. They performed a manual post-processing step to fix errors (like missing articles or misaligned spans).

Table 8 highlights the effort involved in this validation. The “Train (ES)” set required 450 corrections. This hybrid approach—automation followed by human verification—allowed them to create a high-quality 4-language dataset with a fraction of the effort required for full manual annotation.

Experiments: Can AI Detect the Arguments?

With the dataset built, the researchers moved to the experimental phase. The task was Argument Component Detection: Can we feed a medical explanation into an AI model and have it correctly highlight the Claims and Premises?

They tested several types of Large Language Models:

- Encoder Models: BERT and DeBERTa (traditional models excellent for classification).

- Encoder-Decoder Models: Medical mT5 (specifically trained on medical text).

- Decoder-only (Generative) Models: LLaMA-2 and Mistral (the modern style of LLMs).

The “Data Transfer” Strategy

The researchers compared different training strategies. The most successful approach was Multilingual Data-Transfer. Instead of training a model only on Spanish data to test on Spanish, they pooled the training data from all four languages together.

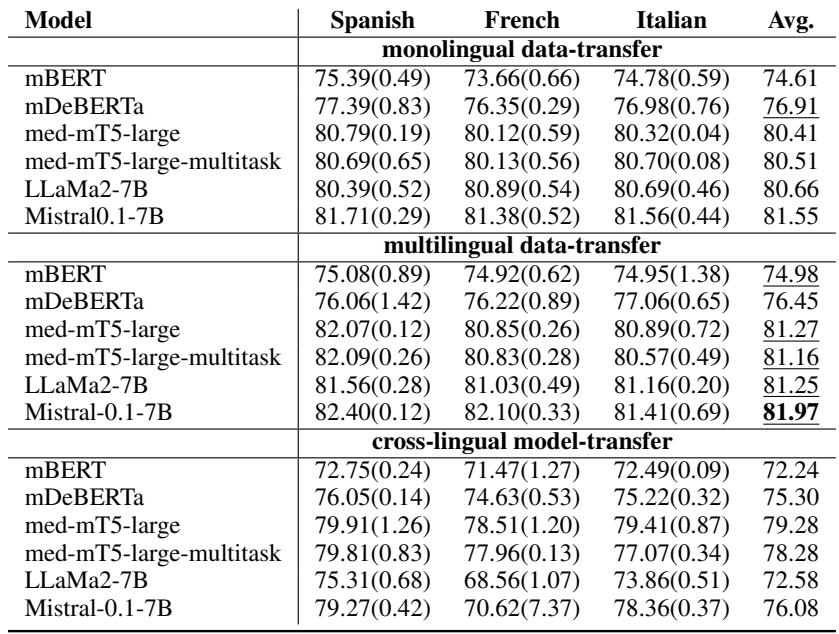

Table 7 provides a fascinating look at the results. Here are the key takeaways:

- More Data is Better: The rows labeled “multilingual data-transfer” almost consistently outperform the monolingual settings. By seeing examples of medical arguments in Italian and English, the model becomes better at spotting them in Spanish.

- Generative Models Shine: The Mistral-0.1-7B model achieved the highest scores across the board (around 81-82% F1 score). This is notable because Sequence Labeling (highlighting text) has traditionally been the domain of encoder models like BERT. This shows that modern Generative LLMs are becoming surprisingly adept at structured tasks.

- Medical Specialization Matters: The Medical mT5 model (specifically adapted for medicine) performed very competitively, beating the general-purpose LLaMA-2 in several settings.

Why This Matters

The creation of CasiMedicos-Arg is a significant step forward for two main reasons:

1. Explainable AI (XAI) in Medicine: We are moving past the era where a high accuracy score on a benchmark is enough. For AI to be trusted in a hospital, it needs to “show its work.” By training models on this dataset, developers can create systems that output the correct diagnosis and highlight the specific evidence in the patient’s file that supports it, while flagging evidence that contradicts other possibilities.

2. Multilingual Equity: Medical knowledge shouldn’t be locked behind a language barrier. By proving that multilingual data transfer works effectively, this paper offers a blueprint for how to improve medical AI for under-represented languages. Training a model on English data can actually help it perform better in Italian or Spanish, provided the alignment is handled correctly.

Conclusion

The CasiMedicos-Arg paper moves the goalposts for Medical QA. It reminds us that in high-stakes fields like medicine, the argument is just as important as the answer.

The researchers have provided the community with a robust, multilingual dataset that captures the nuance of clinical reasoning. They have demonstrated that combining human expertise with automated projection techniques is a viable path to creating multilingual resources. And finally, they have shown that modern LLMs, particularly when trained on diverse multilingual data, are capable of understanding the complex structure of medical arguments.

As these models continue to evolve, we can look forward to AI assistants that don’t just act as search engines, but as reasoning partners that can help doctors think through complex cases in any language.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2410.05235/images/cover.png)