There is a popular conceptualization of Large Language Models (LLMs) as “multiverse generators.” When you ask a model to complete a sentence, it isn’t just predicting the next word in one specific narrative; it is effectively weighing probabilities across countless potential continuations.

But what happens when the prompt itself is ambiguous? What if the context provided to the model contains examples of two completely different tasks mixed together? Does the model get confused? Does it arbitrarily pick one path and stick to it?

Recent research from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, University of Michigan, and Microsoft Research reveals a fascinating phenomenon: Task Superposition.

In a paper aptly titled “Everything Everywhere All At Once,” researchers demonstrate that LLMs do not simply flip a coin to decide which task to perform. Instead, they perform multiple, computationally distinct tasks simultaneously within a single inference call. It’s as if the model exists in a quantum superposition of intents, calculating the correct answer for translation, arithmetic, and formatting all at the same time, weighing them based on the context provided.

In this deep dive, we will explore this surprising capability, the mechanisms that drive it (including “task vectors”), and what it tells us about the fundamental nature of Transformer architectures.

The Phenomenon of Task Superposition

To understand task superposition, we first need to look at In-Context Learning (ICL). ICL is the ability of a model to learn a new task simply by seeing a few examples in the prompt, without any parameter updates.

Usually, we assume the prompt defines a single task. For example:

- Prompt: “English: Hello, Spanish: Hola. English: Dog, Spanish: Perro. English: Cat, Spanish: …”

- Task: Translate to Spanish.

But consider a prompt that mixes examples. What if we give the model examples of adding numbers, and also examples of translating numbers into French?

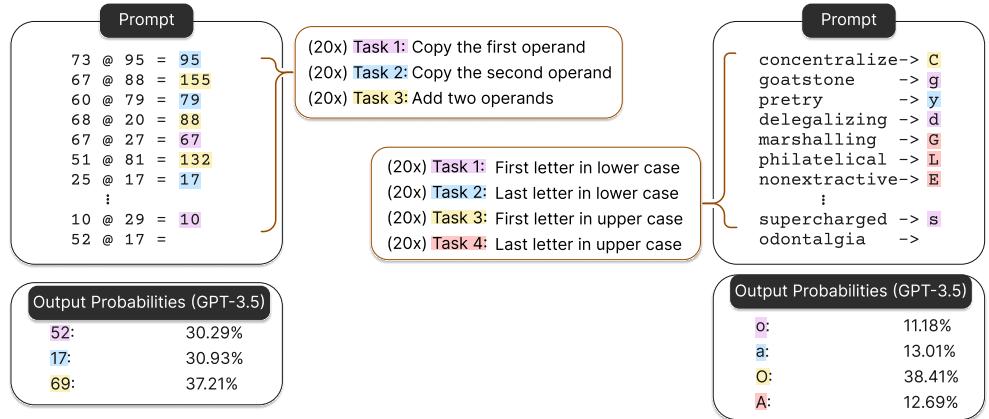

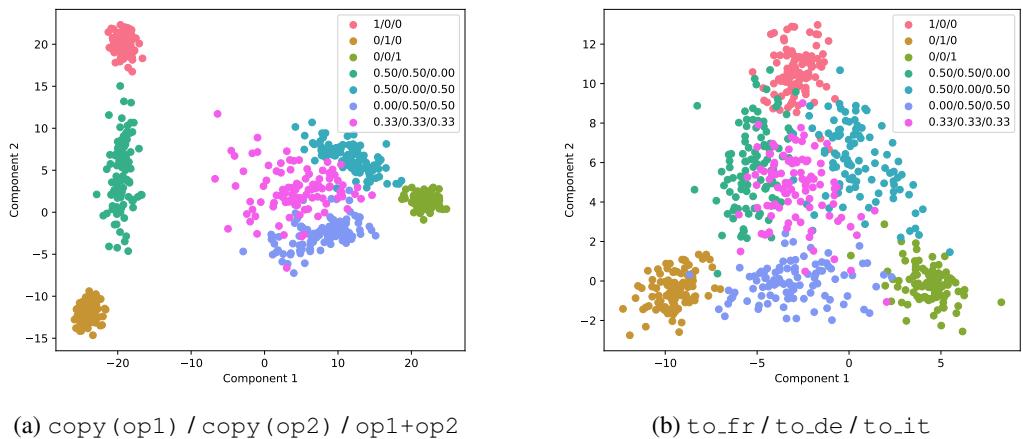

As shown in Figure 1 above, the researchers constructed prompts containing mixtures of tasks.

- Left (Figure 1a): The prompt includes arithmetic examples (“91 + 83”) where the answer formats vary (digits, English words, French words, Spanish words).

- Right (Figure 1b): The prompt mixes tasks like “Copy the first number” and “Add the two numbers.”

When the researchers queried the model (e.g., “91 + 83 ->”), they didn’t just look at the single generated text output. They looked at the probability distribution over the next tokens.

The result was striking. The model assigned significant probability mass to all valid answers corresponding to the tasks present in the context. It didn’t just pick “French” or “Digits.” It prepared valid answers for both simultaneously.

The Simulator Perspective

This aligns with the view of LLMs as “superposition of simulators.” If we treat the LLM as a Bayesian inference engine, it is trying to infer the latent variable—the “task”—given the prompt. If the prompt is ambiguous (containing examples of Task A and Task B), the model constructs a probability distribution that is a weighted sum of both tasks.

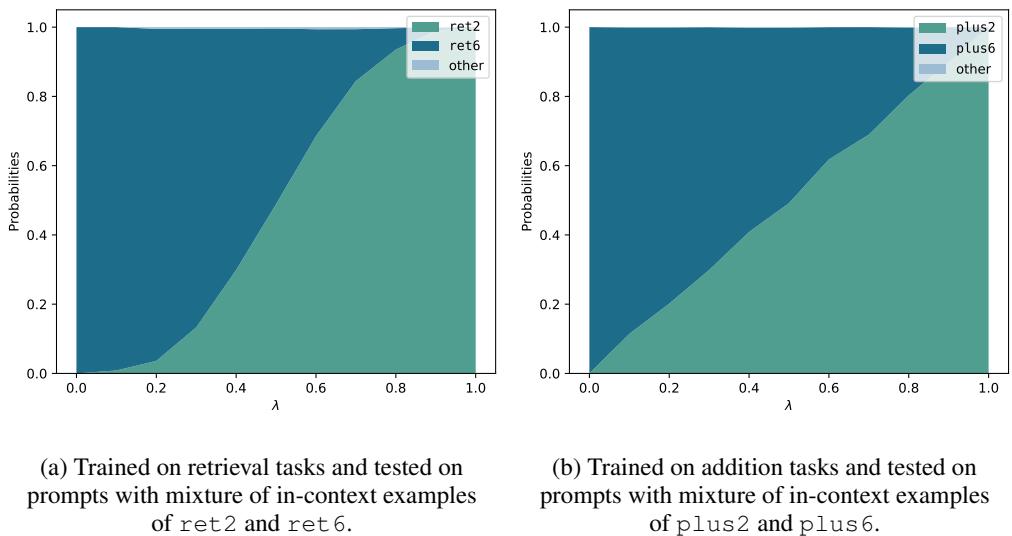

Mathematically, the researchers conceptualize this as:

Here:

- \(P(output | task, prompt)\) is the likelihood of an answer if the model were strictly doing one specific task.

- \(P(task | prompt)\) is the model’s estimation of how likely that task is, based on the mix of examples in the context.

Empirical Evidence: It’s Not a Fluke

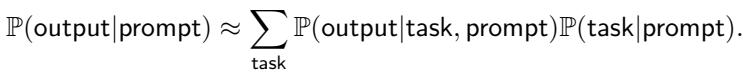

This behavior isn’t limited to a specific model or a specific type of task. The researchers tested this on GPT-3.5, Llama-3 70B, and Qwen-1.5 72B across four distinct experimental settings:

- Multilingual Addition: Numerical addition vs. addition in English, French, or Spanish.

- Geography: Naming a capital vs. a continent vs. capitalizing the country name.

- Arithmetic Logic: Copying operands vs. adding them.

- String Manipulation: First letter vs. last letter, uppercase vs. lowercase.

In every case, they fed the models prompts with 20 in-context examples, randomized to include different mixtures of tasks.

Figure 2 shows the results. The y-axis represents the probability assigned to the correct answer for a specific task.

- In Figure 2a (Addition), Llama-3 (brown) assigns probability to both numerical addition (“add”) and language-based addition (“add in en/fr/es”).

- In Figure 2b (Geography), GPT-3.5 (purple) splits its probability mass between naming the capital and naming the continent.

Crucially, the models don’t split these probabilities perfectly evenly. They have biases—some prefer English, others prefer numerical answers—but the median probability for multiple distinct tasks is non-negligible. This confirms that the models are running these processes in parallel.

Emergence: Can You Learn Superposition from Scratch?

A skeptic might argue: “These massive models (GPT-4, Llama-3) have seen everything on the internet. Maybe they just memorized mixed data?”

To test if superposition is a fundamental property of the Transformer architecture rather than just a quirk of massive datasets, the researchers performed a controlled experiment. They trained a small GPT-2 model (86M parameters) from scratch.

The Training Setup

They created a synthetic dataset of distinct tasks:

- Retrieval: Given a string of 8 characters, retrieve the 1st, 2nd, … or 8th character.

- Arithmetic: Given a number, add 0, add 1, … or add 9.

Crucially, the model was trained to learn only one task at a time. During training, every prompt contained examples from only one specific task (e.g., only “retrieve the 3rd character”). The model never saw mixed tasks during training.

The Test

At inference time, they presented the model with a mixture of examples (e.g., 50% “retrieve 2nd char” and 50% “retrieve 6th char”).

If the model merely learned to classify a prompt into a single bucket, it should fail or randomly pick one. Instead, the model exhibited perfect superposition.

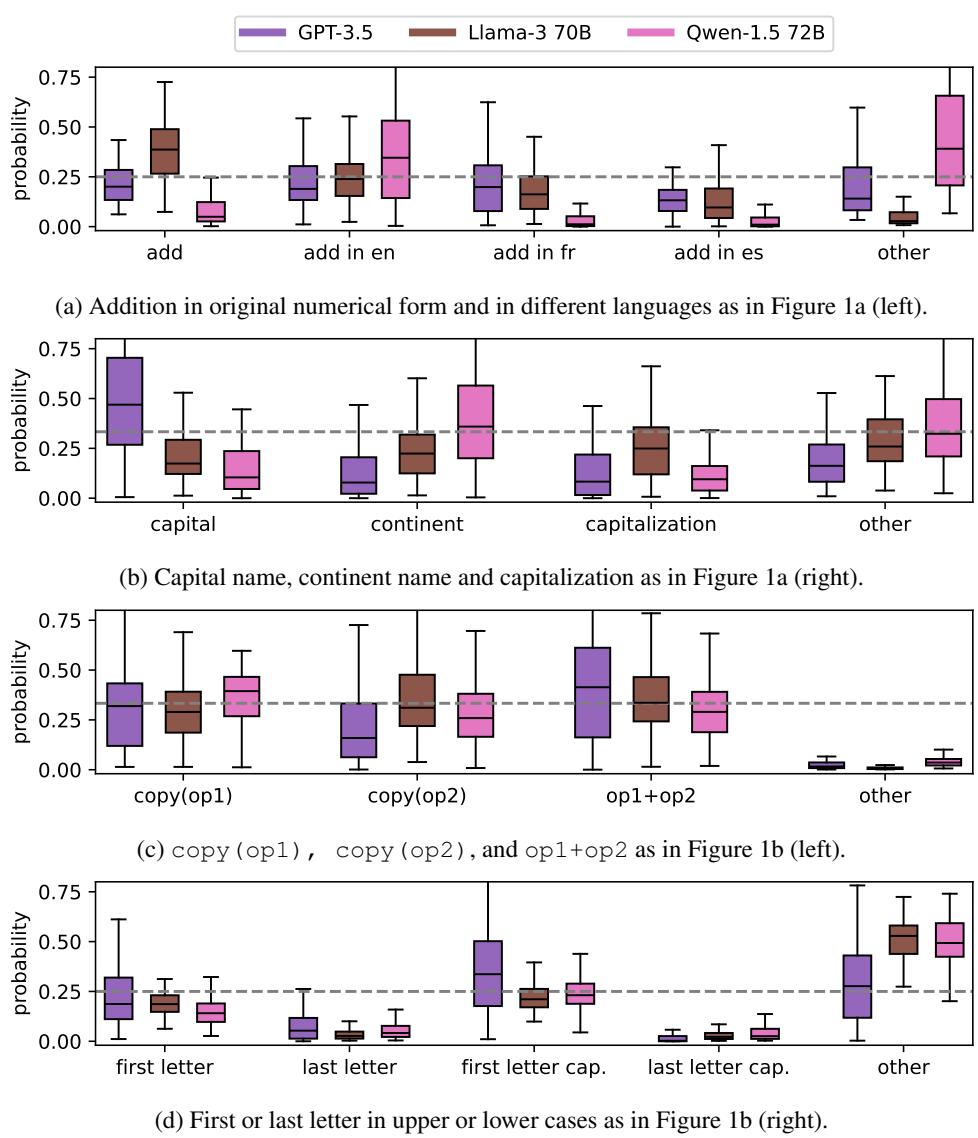

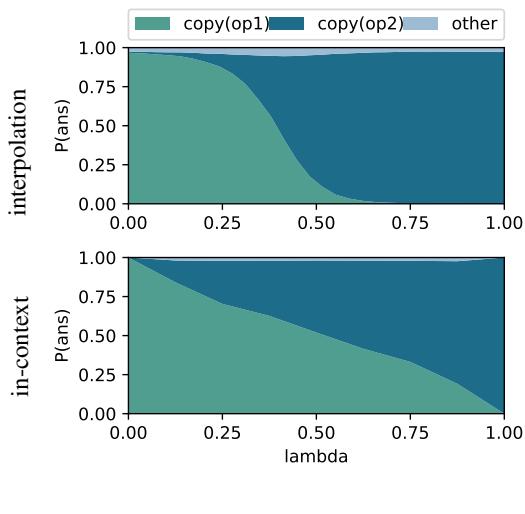

Figure 3 illustrates this emergent behavior.

- The x-axis (\(\lambda\)) represents the proportion of Task A examples in the prompt.

- The y-axis is the probability of the output matching Task A (teal) or Task B (dark blue).

As the mix of examples shifts from 0% to 100%, the model’s output probabilities shift smoothly and linearly. At \(\lambda = 0.5\) (50/50 mix), the model assigns roughly equal probability to both answers.

Finding: Transformers can learn to perform task superposition even if they are never trained on mixed tasks. It is an inherent capability of the architecture to aggregate context.

The Mechanism: Task Vectors

How does the model actually do this? Does it have separate circuits firing for each task?

The researchers analyzed the internal state of the models using Task Vectors. A task vector is a direction in the model’s activation space (specifically in the Multi-Head Attention layers) that encodes a specific capability. Previous research has shown that adding a “French task vector” to a model can make it speak French.

The researchers extracted task vectors for single tasks (e.g., a vector for “Translation to French” and a vector for “Translation to German”). Then, they looked at the vectors produced when the model processed a mixed prompt.

Vector Geometry

They projected these high-dimensional vectors onto a 2D plane using Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA).

Figure 4 visualizes these vectors. The corners of the triangle (Pink, Brown, Green) represent the pure tasks. The intermediate points (Cyan, Blue, Magenta) represent the mixed prompts.

- Result: The vector for a mixed task lies geometrically between the vectors for the single tasks.

- If you prompt the model with 50% Task A and 50% Task B, the resulting internal state is remarkably close to the mathematical average of Vector A and Vector B.

Hacking the Model with Math

This geometric relationship implies we might not even need the prompt. Can we force the model into superposition just by doing math on its internal neurons?

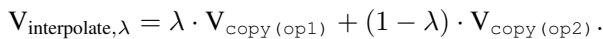

The researchers tested this by manually constructing a task vector using a convex combination (weighted sum) of two single-task vectors:

They “patched” this artificial vector into Llama-3 and compared the result to prompting the model with mixed examples.

Figure 5 shows the comparison.

- Top Row (Interpolation): The output probabilities resulting from mathematically mixing the vectors.

- Bottom Row (In-Context): The output probabilities resulting from mixing the prompt examples.

While not identical, the trends are strikingly similar. By simply adding the “Translate to German” vector to the “Translate to Italian” vector, the model begins to output probabilities for both languages simultaneously. This suggests that linear combination of task vectors is the primary mechanism by which LLMs implement superposition.

Theoretical Proof: The Transformer Capacity

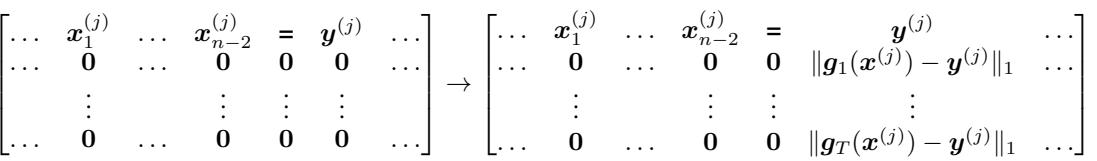

The researchers didn’t stop at empirical observation. They provided a theoretical construction proving that a standard Transformer architecture is expressive enough to perform this superposition.

They proved Theorem 1: A seven-layer transformer can perform K tasks in superposition.

The construction involves a specific architectural logic:

- Task Identification: The model uses early layers to compare the input examples \((x, y)\) against its internal repertoire of functions. It calculates the error (difference) between what the function predicts and the actual label \(y\).

- Indicator Vectors: If the error is near zero, the model generates a “flag” (an indicator vector) saying, “This example matches Task A.”

- Weighting: The model averages these flags across all examples in the context. If 70% of examples match Task A, the weight for Task A becomes 0.7.

- Superposition: In the final layers, the model executes all tasks in parallel heads. The final output is a sum of the outputs of these heads, weighted by the calculated proportions.

The matrix below visualizes a step in this theoretical construction, where the model calculates the difference between the actual label \(y^{(j)}\) and the predicted label \(g(x^{(j)})\) to identify the task:

This theoretical framework confirms that the phenomenon observed in GPT-4 and Llama-3 isn’t magic; it is a mathematically provable capability of the attention mechanism.

Scaling Laws: Bigger is Better

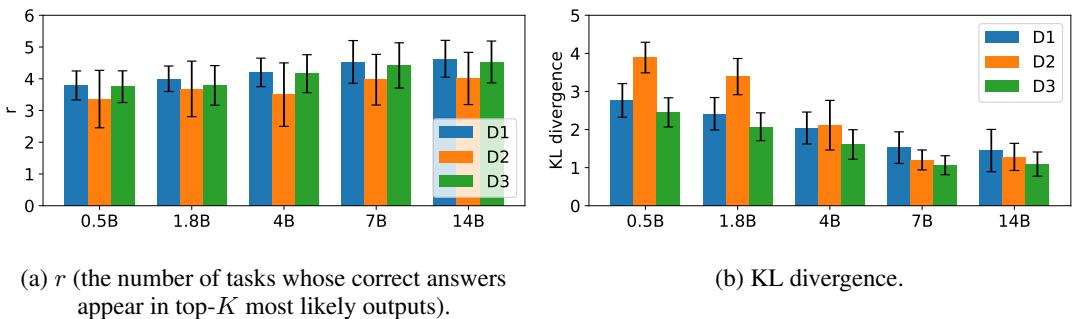

Finally, the paper explores how model size affects this capability. They compared members of the Qwen-1.5 family ranging from 0.5 billion to 14 billion parameters.

They measured two metrics:

- \(r\) (Tasks Completed): How many distinct tasks appear in the top-K probability outputs?

- KL Divergence: How accurately does the model’s output probability match the input mixture? (e.g., if the prompt is 25% Task A, is the output probability 25%?)

As shown in Figure 6:

- Left (a): The number of tasks (\(r\)) the model can maintain in superposition increases with model size.

- Right (b): The KL divergence decreases with size (lower is better).

Implication: Larger models are not just better at solving hard problems; they are better at maintaining multiple competing hypotheses simultaneously. They are better simulators.

Conclusion and The “Generation Collapse”

This research fundamentally shifts how we view the “inference” step of an LLM. We often think of the model as making a decision and then generating text. In reality, during the processing of the prompt, the model is “everything, everywhere, all at once”—calculating the result of every relevant task it recognizes in the context.

However, there is a limitation: Generation Collapse. While the model calculates the probabilities for multiple tasks, it can usually only output one sequence of text. Once it picks the first token (e.g., the first digit of a sum), the context for the next token shifts, and the superposition collapses into a single specific task.

The authors suggest that future decoding algorithms could exploit this. Imagine “Superposed Decoding,” where a model could output multiple streams of answers (translation, summary, and code) from a single pass, simply by keeping the superposition alive.

For students of AI, this paper highlights the power of the high-dimensional latent space. It turns out that in 4,000 dimensions, you don’t have to choose between Task A and Task B. You can simply choose the space in between.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2410.05603/images/cover.png)