Beyond SFT: Aligning LLMs with Generalized Self-Imitation Learning (GSIL)

Large Language Models (LLMs) are impressive, but raw pre-trained models are like brilliant but unruly students. They know a lot about the world, but they don’t always know how to behave, follow instructions, or solve complex problems step-by-step. To fix this, we perform a process called alignment.

Currently, the standard recipe for alignment has two main stages:

- Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT): You show the model examples of good prompts and responses, and it learns to copy them.

- Preference Fine-Tuning (RLHF/DPO): You show the model two responses (one good, one bad) and teach it to prefer the good one.

The second stage is powerful but expensive. It requires collecting human preference data (“Response A is better than Response B”), which is costly and slow to scale. What if we could achieve the high performance of preference learning using only the demonstration data from the first stage?

In this post, we dive into a fascinating paper titled “How to Leverage Demonstration Data in Alignment for Large Language Model? A Self-Imitation Learning Perspective.” The researchers propose a new framework called GSIL (Generalized Self-Imitation Learning). It turns the alignment problem into a classification task, allowing the model to learn from itself and outperform standard methods without needing expensive preference labels.

The Problem with Standard Imitation

To understand why we need GSIL, we first need to look at why the standard approach, Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT), isn’t enough.

SFT is essentially Behavior Cloning. We give the model a prompt (\(\mathbf{x}\)) and a gold-standard human response (\(\mathbf{y}\)), and we minimize the negative log-likelihood. In other words, we tell the model: “Maximize the probability of generating these exact words.”

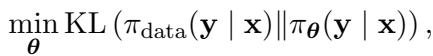

Mathematically, SFT minimizes the Forward KL Divergence between the data distribution and the model distribution:

While this sounds logical, it has a hidden flaw known as mass-covering behavior. By trying to cover the entire distribution of human data, the model tries to assign probability to every possible human response. But human data is noisy. If the training data contains both high-quality reasoning and mediocre reasoning, SFT tries to average them out.

In complex tasks like coding or math, “averaging” is disastrous. We don’t want the model to cover all valid human responses; we want it to find the best distinct mode of high-quality answers. We want mode-seeking behavior.

This is where the distinction between Forward KL (used in SFT) and Reverse KL becomes critical.

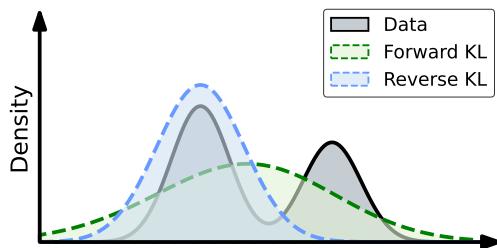

As illustrated in Figure 1 above:

- SFT (Forward KL): The green dashed line tries to cover the entire black curve (Data). It spreads itself thin, potentially including low-probability or noisy regions.

- GSIL (Reverse KL): The blue dot-dashed line focuses on the peak (the mode). It ignores the tails and focuses on the highest density of good data.

The researchers argue that for high-performance alignment, we should be minimizing the Reverse KL Divergence.

The Core Method: Generalized Self-Imitation Learning (GSIL)

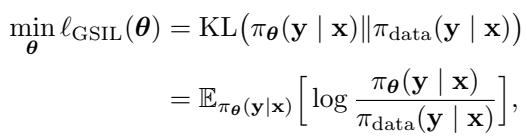

The goal of GSIL is to minimize the reverse KL divergence. This objective looks like this:

The Challenge

There is a catch. Minimizing Reverse KL is much harder than Forward KL. To optimize Equation (6), you need to calculate the ratio between the data distribution \(\pi_{\text{data}}\) and the model’s current policy \(\pi_{\theta}\). But we don’t have a formula for the “data distribution”—we only have a dataset of samples.

In Reinforcement Learning (RL), this is usually solved using complex adversarial training (like GANs), where you train a separate “discriminator” network to tell real data from fake data. But that is notoriously unstable and computationally heavy.

The Surrogate Objective

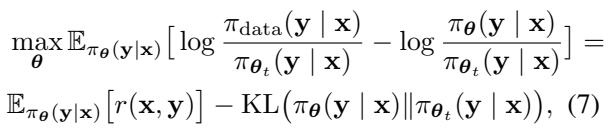

The authors propose a clever workaround. They derive a surrogate objective that transforms the problem. Instead of a complex RL loop, they treat the problem as maximizing a reward function based on the density ratio between real data and the model’s own generations.

Here, \(r(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y})\) acts as a reward, defined by the log ratio of the data probability to the model probability. If the model can estimate this ratio, it can push its generation toward the real data distribution.

Density Ratio Estimation (DRE)

How do we estimate this ratio without a separate reward model? We turn it into a classification problem.

Imagine we mix real human demonstrations (labeled 1) and the model’s own generated responses (labeled 0). We can train a classifier to distinguish between them. The paper shows that the optimal classifier for this task is directly related to the density ratio we need.

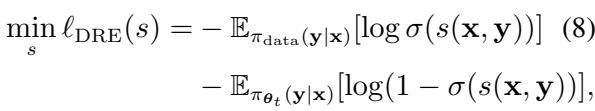

The loss function for this density ratio estimation (DRE) looks like standard logistic regression:

The “Self-Imitation” Twist

Here is the most elegant part of GSIL. Instead of training a separate classifier network (a discriminator) and a generator network (the LLM), the authors use the LLM itself to parametrize the discriminator.

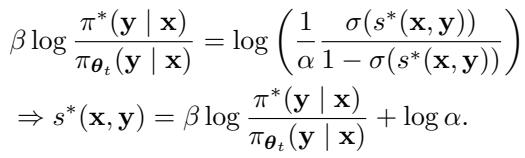

They derive a closed-form solution where the optimal discriminator score \(s^*\) is expressed using the model’s policy \(\pi\):

By substituting this back into the loss function, we get a direct optimization objective for the Language Model. We don’t need a separate reward model or a PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization) loop. We just minimize a classification loss where the “logits” are the log-probabilities of the LLM itself.

The final GSIL Objective looks like this:

What Does This Mean Intuitively?

The equation above might look intimidating, but the intuition is straightforward:

- Positive Phase: The first term encourages the model to increase the probability of the real demonstration data (treating them as “positive” classes).

- Negative Phase: The second term encourages the model to decrease the probability of its own self-generated data (treating them as “negative” classes), relative to the reference model.

The model learns by contrasting real human expertise against its own current attempts. It is “imitating” the expert by trying to distinguish expert data from its own synthetic babble.

A Generalized Framework

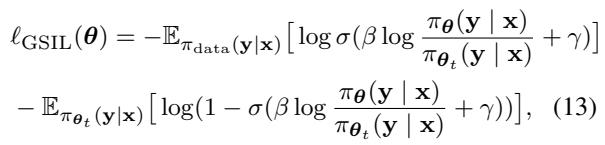

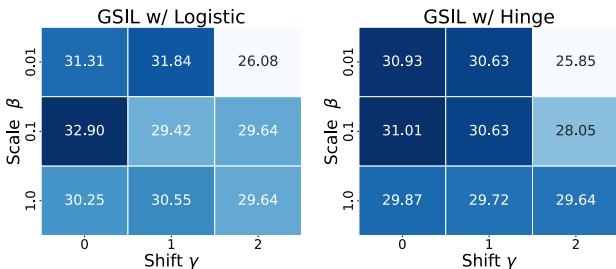

The paper is titled Generalized SIL because this logic isn’t limited to one specific loss function. The derivation above used Logistic Regression, but the authors show that a whole family of loss functions (Hinge loss, Brier score, Exponential loss) can be plugged into this framework.

As shown in Figure 10, different loss functions impose different penalties (margins) on the difference between the expert data and generated data. This flexibility allows GSIL to adapt to different types of tasks.

Comparison with SPIN

You might be wondering, “Isn’t this similar to other self-play methods like SPIN?”

SPIN (Self-Play Fine-Tuning) is a recent method that also uses demonstration data. However, SPIN relies on the Bradley-Terry preference model, which assumes a symmetric relationship between winning and losing responses.

The authors found that SPIN has a side effect: while it pushes down the probability of generated responses (which is good), it can inadvertently push down the probability of real demonstrations too.

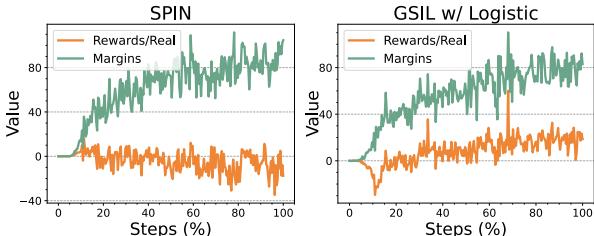

Look at the orange lines in Figure 2.

- Left (SPIN): The reward (implicit likelihood) of the Real data drops below zero over time. The model is “unlearning” the good data while trying to distance itself from the bad data.

- Right (GSIL): The reward for Real data keeps increasing or stays positive. GSIL maintains the high probability of the expert demonstrations while widening the gap (margin) to the synthetic data.

This is crucial for tasks like math or coding, where the “Real” answer is often the only correct answer, and lowering its probability is harmful.

Experiments & Results

To prove that this isn’t just theoretical gymnastics, the authors tested GSIL on several challenging benchmarks:

- Reasoning: ARC, Winogrande

- Math: GSM8K

- Coding: HumanEval

- Instruction Following: MT-Bench

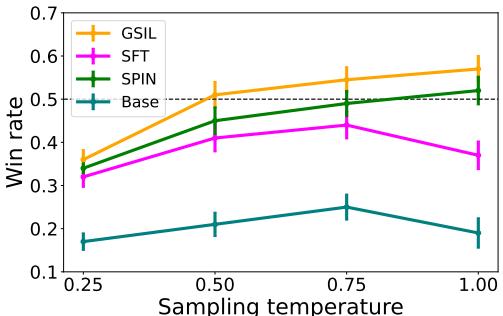

They compared GSIL against standard SFT and SPIN.

Main Results

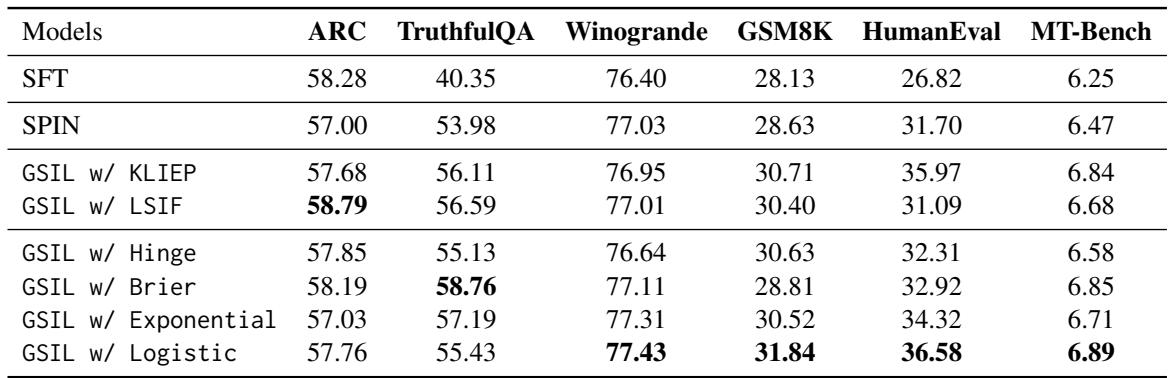

The results are highly impressive. GSIL consistently outperforms SFT and SPIN across the board.

Key takeaways from Table 2:

- Beating SFT: GSIL improves upon SFT significantly. For example, on the coding benchmark (HumanEval), SFT scores 26.82, while GSIL (Logistic) scores 36.58. That is a massive jump using the exact same data.

- Beating SPIN: GSIL outperforms SPIN, particularly in Math and Code. This validates the hypothesis that SPIN’s tendency to lower real-data probability hurts performance in exact-reasoning tasks.

- Loss Functions: While Logistic loss (standard) works great, other losses like Brier also show strong performance, highlighting the benefit of the generalized framework.

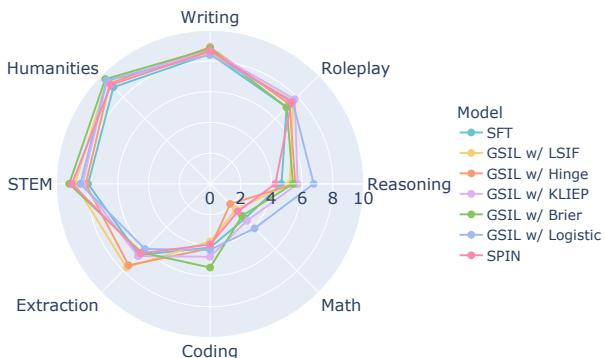

We can visualize these gains across different capabilities using the radar chart below:

GSIL (the colored lines) pushes the boundaries outward compared to SFT (blue) and SPIN (orange), especially in Reasoning, Math, and Coding.

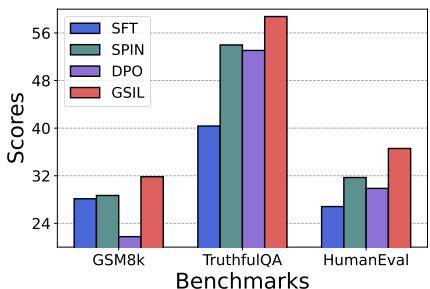

Can it Beat Preference Tuning (DPO)?

Perhaps the most surprising result is how GSIL compares to DPO. Remember, DPO requires preference pairs (human annotations of “better vs. worse”). GSIL only uses demonstrations.

As Figure 6 shows, GSIL (blue bar) actually outperforms DPO (green bar) on GSM8K (Math), TruthfulQA, and HumanEval. This suggests that for reasoning-heavy tasks, a strong self-imitation signal on good data might be more valuable than noisy preference signals.

Safety Alignment

Does maximizing likelihood make the model unsafe? The authors tested this on the Anthropic-HH dataset (Helpful and Harmless).

GSIL achieves a ~60% win rate against the chosen responses, significantly higher than the SFT baseline (which hovers around 50%). This means the model isn’t just getting smarter; it’s adhering better to safety guidelines present in the training data.

Hyperparameters Matter

The framework introduces two key hyperparameters:

- \(\beta\): A scaling parameter (similar to the temperature in DPO).

- \(\gamma\) (Shift): A parameter that controls the prior weight given to the demonstration data.

The ablation study in Figure 7 reveals that a strictly positive \(\gamma\) (Shift) helps performance. This mathematically corresponds to assigning a higher “prior probability” to the real data class, preventing the model from becoming confused between real and synthetic data.

Conclusion

The paper “How to Leverage Demonstration Data in Alignment” offers a compelling new perspective on LLM training. It challenges the assumption that we strictly need Reinforcement Learning or expensive Preference Data to align models effectively.

By reframing alignment as Generalized Self-Imitation Learning (GSIL), the authors provide a method that is:

- Effective: It achieves mode-seeking behavior (Reverse KL), crucial for reasoning and coding.

- Efficient: It avoids the complexity of adversarial training or PPO.

- Self-Contained: It unlocks greater performance from the demonstration data you already have.

For students and practitioners, GSIL represents a shift in thinking. Instead of just teaching a model to “copy” (SFT), we can teach it to “discriminate and self-improve,” treating its own generations as negative examples to push against. As we look for ways to make LLM training more data-efficient, techniques like GSIL that squeeze more signal out of existing data will likely become the new standard.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2410.10093/images/cover.png)