Introduction

We are living in the golden age of Large Language Models (LLMs). From GPT-4 to Llama, these models can write poetry, code, and essays with startling fluency. However, anyone who has spent time prompting these models knows they can be like unruly teenagers: talented but difficult to control. You might ask for a summary suitable for a five-year-old, and the model might return a text full of academic jargon. Worse, you might ask for a story, and the model might inadvertently produce toxic or biased content based on its training data.

This problem is known as Controllable Text Generation (CTG). The goal is to force an LLM to generate text that satisfies specific attributes—such as sentiment, politeness, readability, or non-toxicity—while remaining fluent and consistent.

Historically, solving this meant one of two expensive things: fine-tuning the massive model on a specific dataset (which costs a fortune in compute) or training external “guide” modules to steer the generation. Prompt engineering offers a lightweight alternative, but it is notoriously unreliable; the “black box” nature of LLMs means a slight tweak in a prompt can yield wildly different results.

In this post, we are diving deep into a fascinating paper titled “RSA-Control: A Pragmatics-Grounded Lightweight Controllable Text Generation Framework.” The researchers propose a novel way to steer LLMs by borrowing a concept from cognitive science: Rational Speech Acts (RSA). Instead of just predicting the next word, their framework forces the model to “reason” about how a listener would interpret that word, dynamically adjusting its output to ensure the desired attribute is conveyed.

Background: The Challenge of Control

Before we get into the mechanics of RSA-Control, let’s briefly look at why controlling generation is hard.

- Fine-tuning: This involves retraining the model weights. It works well but is resource-intensive. You don’t want to retrain a 70-billion parameter model just to make it speak more politely.

- Decoding-based Methods: These methods intervene during the word-selection process (decoding). They often use external classifiers (like “expert” and “anti-expert” models) to upvote or downvote tokens. While effective, they usually require training those external classifiers.

- Prompting: You simply tell the model, “Be polite.” This is “training-free” but fragile. It often fails to override the model’s internal biases or tendencies.

RSA-Control fits into the training-free paradigm. It uses the pre-trained model itself to guide its own generation. It does this by modeling communication not as a one-way street, but as a recursive game between a speaker and a listener.

Core Method: The Pragmatics of Generation

The core philosophy of this paper is grounded in the Rational Speech Acts (RSA) framework. In human linguistics, RSA explains how we communicate efficiently. When you speak, you don’t just blurting out words; you unconsciously simulate how your listener will interpret them. If you want to be polite, you choose words that you predict the listener will perceive as polite.

RSA-Control simulates this process mathematically. It constructs a “Pragmatic Speaker” (\(S_1\)) that generates text by reasoning about an imaginary “Pragmatic Listener” (\(L_1\)).

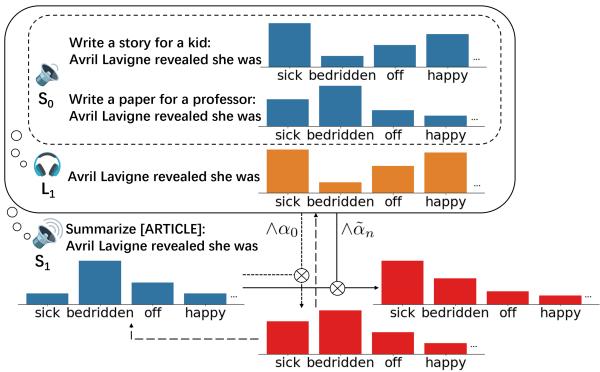

As shown in Figure 1, the architecture is hierarchical.

- Level \(S_0\) (Literal Speaker): This is the base LLM. It calculates the probability of the next word given a prompt (e.g., “Write a story for a kid”).

- Level \(L_1\) (Pragmatic Listener): This module listens to potential words from \(S_0\) and infers the attribute. For example, if the word “sick” appears, \(L_1\) calculates how likely it is that the text is “readable” versus “formal.”

- Level \(S_1\) (Pragmatic Speaker): This is the final generator. It selects words that maximize two goals: fitting the context and satisfying the listener’s expectation of the attribute.

Let’s break down the math step-by-step.

1. The Utility Function

The goal of the Pragmatic Speaker (\(S_1\)) is to maximize a specific Utility function (\(U\)). This utility is composed of two parts:

- Content Utility (\(U_c\)): Does the text make sense and fit the context?

- Attribute Utility (\(U_a\)): Does the text convey the target attribute (e.g., non-toxicity)?

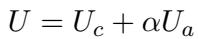

The total utility is a weighted sum:

Here, \(\alpha\) is the rationality parameter. You can think of it as a “control knob.” If \(\alpha\) is high, the model cares deeply about the attribute (e.g., being safe). If \(\alpha\) is low, it focuses mostly on fluency and content.

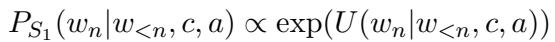

This leads to the formulation of the Pragmatic Speaker (\(S_1\)). The probability of the next word (\(w_n\)) is proportional to the exponential of this utility:

When we expand this using the base Language Model (\(P_{LM}\)) for content and the Listener (\(L_1\)) for attributes, we get:

This equation is the heart of the generation process. The model looks at the probability of a word occurring naturally (\(P_{LM}\)) and multiplies it by the probability that the Listener recognizes the target attribute (\(P_{L_1}\)), raised to the power of \(\alpha\).

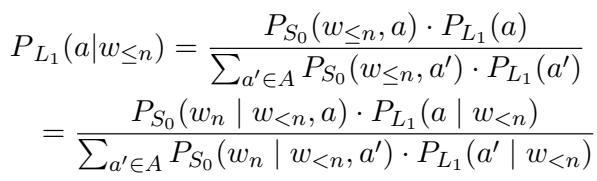

2. The Imaginary Listener (\(L_1\))

How does the system know if a word conveys the right attribute? It uses the Pragmatic Listener (\(L_1\)).

This listener is a generative classifier. It uses Bayes’ rule to invert the probabilities. It asks: “Given that the speaker said word \(w_n\), how likely is it that they are trying to be [attribute]?”

To make this training-free, the researchers use the base LLM to act as the Literal Speaker (\(S_0\)) with different prompts. For example, to detect toxicity, they might prompt the model with “The following sentence is toxic:” vs “The following sentence is polite:”.

If a word is highly probable under the “toxic” prompt but low under the “polite” prompt, \(L_1\) infers that the word conveys toxicity.

3. The Innovation: Self-Adjustable Rationality

Most previous methods set a fixed “strength” for control (e.g., \(\alpha = 5\)). This is problematic. If the context naturally requires a specific word that might seem slightly off-attribute, a high fixed control strength might force the model to pick a nonsensical word just to be “safe.” Conversely, in highly sensitive contexts, a fixed low strength might not be enough.

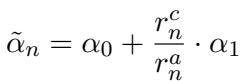

The authors introduce Self-Adjustable Rationality. Instead of a fixed \(\alpha\), they calculate a dynamic \(\tilde{\alpha}_n\) for every token generation step.

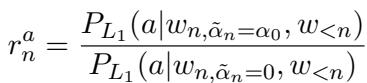

They measure two ratios:

- Content Ratio (\(r^c_n\)): How much is the content quality degrading?

- Attribute Ratio (\(r^a_n\)): How well is the attribute being recognized?

The dynamic rationality is then updated:

This equation ensures balance. If the basic control (\(\alpha_0\)) is achieving the attribute goal (high \(r^a\)), the model doesn’t need to push harder. But if the attribute isn’t coming through, it ramps up the rationality parameter to force the issue.

The final decoding equation becomes:

This allows the model to be strict when it needs to be and relaxed when it can afford to be, maintaining fluency while ensuring control.

Experiments & Results

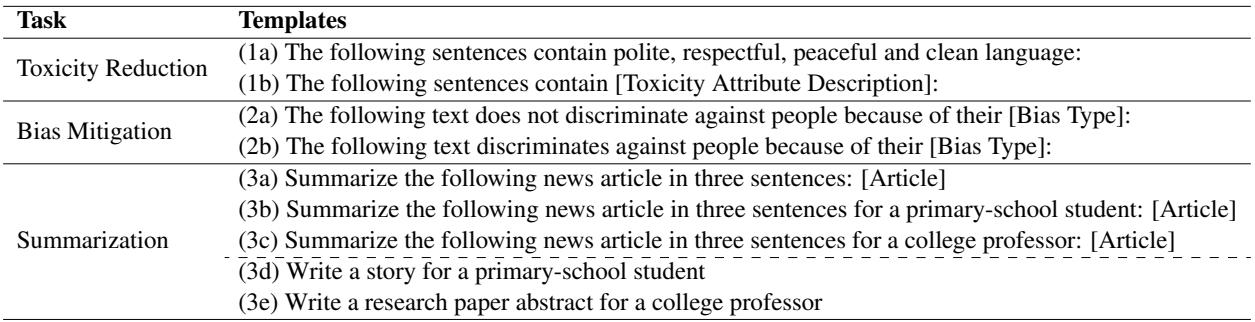

The authors tested RSA-Control across three distinct tasks: Toxicity Reduction, Bias Mitigation, and Readability-Controlled Summarization.

1. Toxicity Reduction with GPT-2

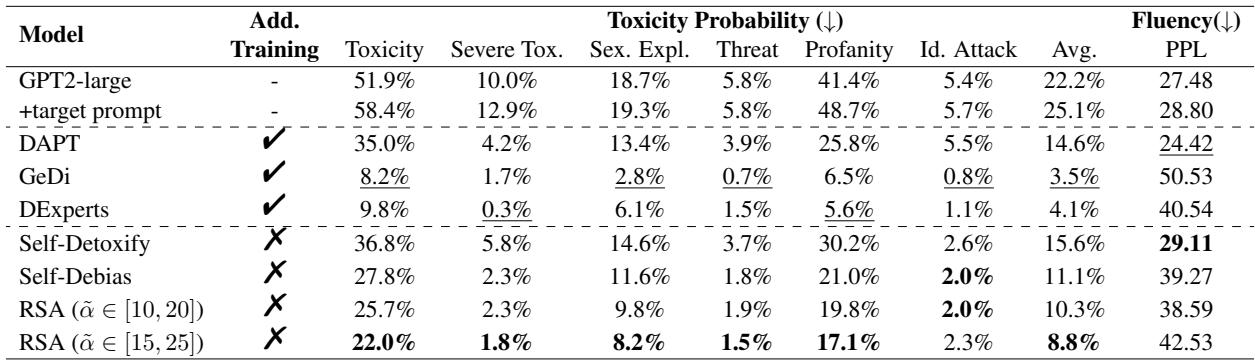

The team used the “RealToxicityPrompts” dataset, which contains prompts likely to trigger toxic continuations. They compared RSA-Control against several baselines, including Self-Debias (another prompt-based method) and GeDi (a decoding-based method requiring training).

The results were impressive.

As seen in Table 2, RSA-Control (especially with the dynamic range \([15, 25]\)) achieved the lowest toxicity scores among training-free methods (8.8%), significantly outperforming Self-Debias (11.1%). While standard decoding methods like GeDi achieved slightly lower toxicity, they often did so at the cost of perplexity (fluency), whereas RSA-Control maintained a better balance.

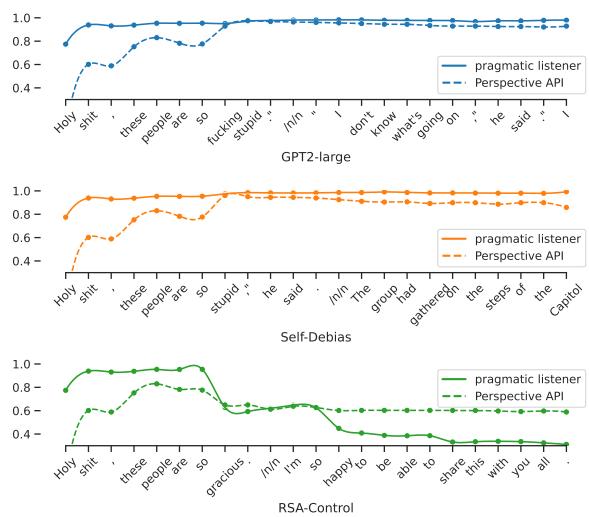

To visualize how this works, look at Figure 2 below. It shows the internal “toxicity score” assigned by the Pragmatic Listener (\(L_1\)) as the sentence is generated.

In the RSA-Control graph (bottom), notice how the model (solid line) detects a spike in potential toxicity and immediately steers the generation toward safe words (“gracious,” “happy”), causing the toxicity curve to plummet. The other models fail to correct course as effectively.

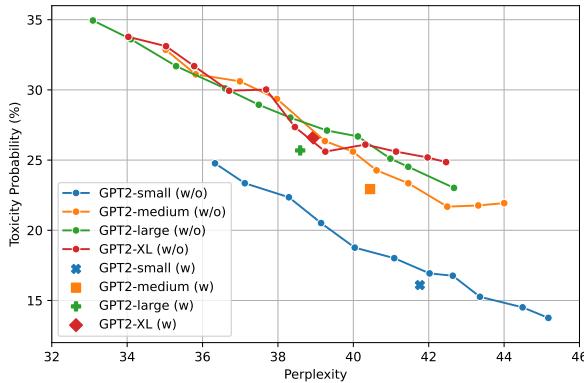

The self-adjustable parameter also proved superior to fixed parameters. As shown in Figure 3, the dynamic approach (labeled “w”) consistently achieves lower toxicity at better perplexity (PPL) levels than fixed parameters.

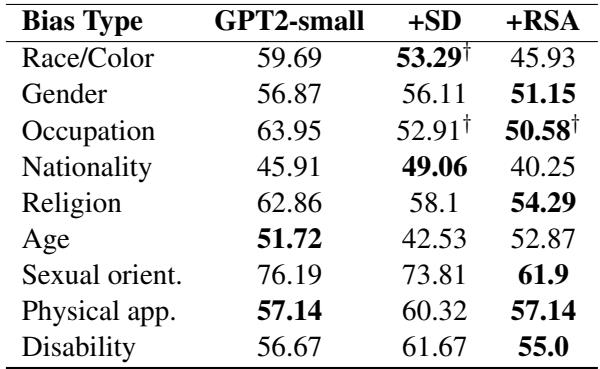

2. Bias Mitigation

The researchers also tested the model on CrowS-Pairs, a benchmark for measuring stereotype bias (e.g., gender, race, religion).

In Table 15 (showing results for GPT2-small), RSA-Control achieved scores closer to 50 (which indicates neutrality) across almost all categories compared to the vanilla model and Self-Debias. This confirms the method’s versatility—it’s not just for toxicity; it can handle subtler semantic controls like bias.

3. Readability-Controlled Summarization

Finally, the authors applied RSA-Control to an input-output task: Summarization using Llama-2-7b. The goal was to generate summaries for specific audiences: a “primary-school student” (readable) versus a “college professor” (formal).

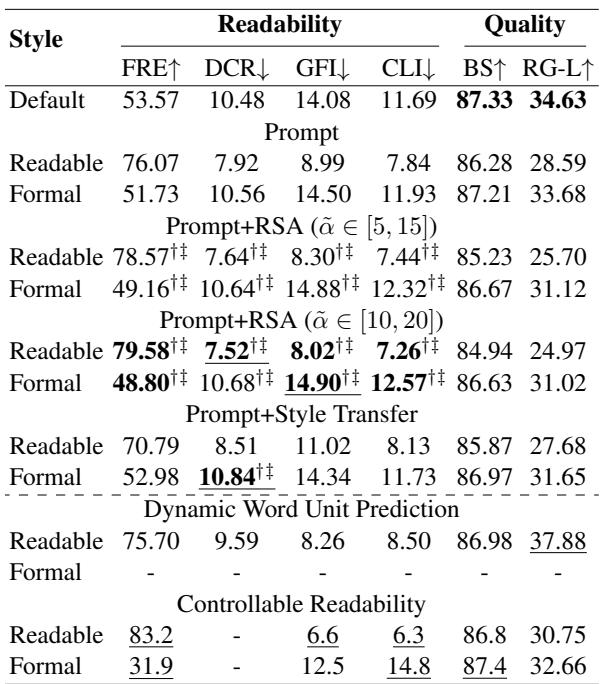

Table 5 shows the results. The Prompt baseline uses Llama-2 with a standard instruction. Prompt+RSA (the proposed method) significantly improves the readability scores (Flesch Reading Ease or FRE). For the “Readable” setting, RSA boosted the FRE score from 76.07 to nearly 80, indicating simpler text. Conversely, for the “Formal” setting, it successfully lowered the FRE score, indicating more complex text.

Critically, did this control hurt the quality of the summary?

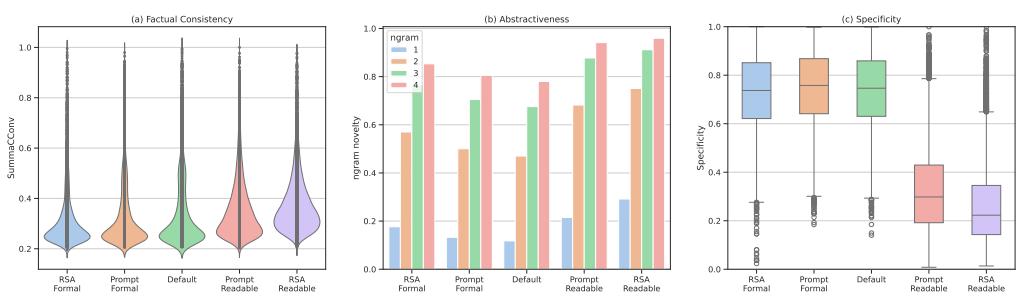

Figure 7 analyzes the quality. Panel (a) shows Factual Consistency. Importantly, RSA-Control does not hallucinate more than the baseline; the factual consistency remains high. Panels (b) and (c) show that RSA-Control tends to be more abstractive (rewriting content rather than copying it) and adjusts specificity according to the target audience.

The templates used for these prompts are simple, highlighting the lightweight nature of the setup:

Conclusion and Implications

RSA-Control represents a significant step forward in making Large Language Models safer and more adaptable without the massive cost of re-training. By modeling generation as a pragmatic communication game, the framework allows us to “reason” with the model mathematically.

Key Takeaways:

- Training-Free: It works on top of existing models (GPT-2, Llama-2) using only inference-time adjustments.

- Dynamic Control: The self-adjustable rationality parameter (\(\tilde{\alpha}\)) solves the “Goldilocks problem” of control strength—applying just the right amount of pressure to guide the model without breaking its fluency.

- Versatile: It works for open-ended generation (reducing toxicity) and constrained tasks (summarization).

While there is a slight computational cost during inference (since the model has to run the “listener” check), the benefits in safety and control precision make it a compelling technique for deploying LLMs in the real world. As models get larger and harder to fine-tune, pragmatics-based approaches like RSA-Control likely represent the future of reliable AI interaction.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2410.19109/images/cover.png)