Have you ever asked an AI to write an essay on a controversial topic? Often, the result looks impressive at first glance. The grammar is perfect, the vocabulary is sophisticated, and the structure seems sound. But if you look closer, cracks begin to appear. The AI might make a bold claim in the first sentence, only to provide evidence that contradicts it three sentences later. Or, it might list facts that are technically true but irrelevant to the argument at hand.

This is a classic problem in Argumentative Essay Generation (AEG). While Large Language Models (LLMs) are excellent at predicting the next word, they often struggle with the high-level architecture of logic. They know how to write, but they often forget why they are writing specific sentences, leading to “logical hallucinations.”

In this post, we will deep dive into a fascinating research paper titled “Prove Your Point!: Bringing Proof-Enhancement Principles to Argumentative Essay Generation.” The researchers propose a new framework called PESA (Proof-Enhancement and Self-Annotation) that teaches AI not just to generate text, but to adhere to strict principles of logic and proof, much like a human debater.

The Problem: Logical Disorganization

Argumentative writing is different from creative writing. It requires a coherent flow where a main thesis is supported by claims, and those claims are supported by specific evidence (grounds).

Current methods often use a “Plan-and-Write” paradigm. They generate a list of keywords or a knowledge graph to guide the essay. However, these plans are often too simple. They tell the model what words to use, but not how to structure the proof.

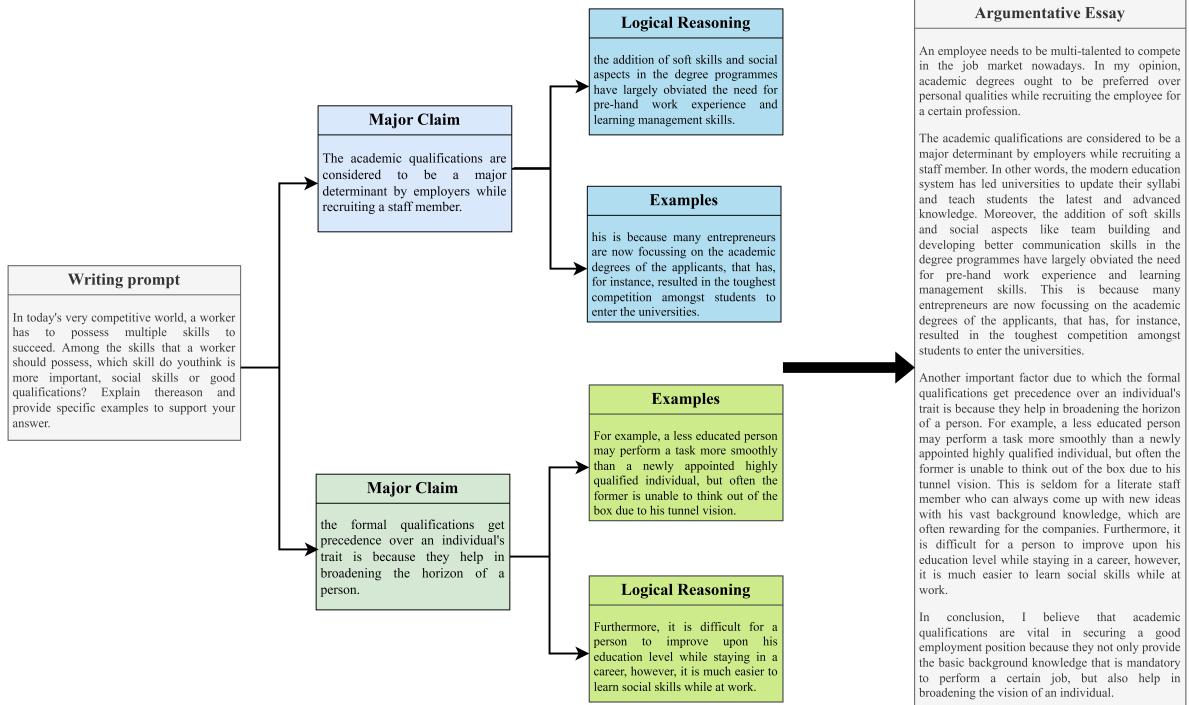

Consider the example below from the research paper. The model is asked to discuss whether public libraries should spend money on high-tech media.

In the upper example (without proof principles), the model claims that technology makes information easier to reach. But in the very next sentence, it provides “evidence” that search engines cannot find information. This is a logical self-contradiction. The lower example, generated using the principles we will discuss today, creates a claim about maintenance costs and supports it with specific data about library funds.

Background: The Toulmin Argumentation Model

To solve this, the researchers turned to a classic theory in philosophy and rhetoric: the Toulmin Argumentation Model.

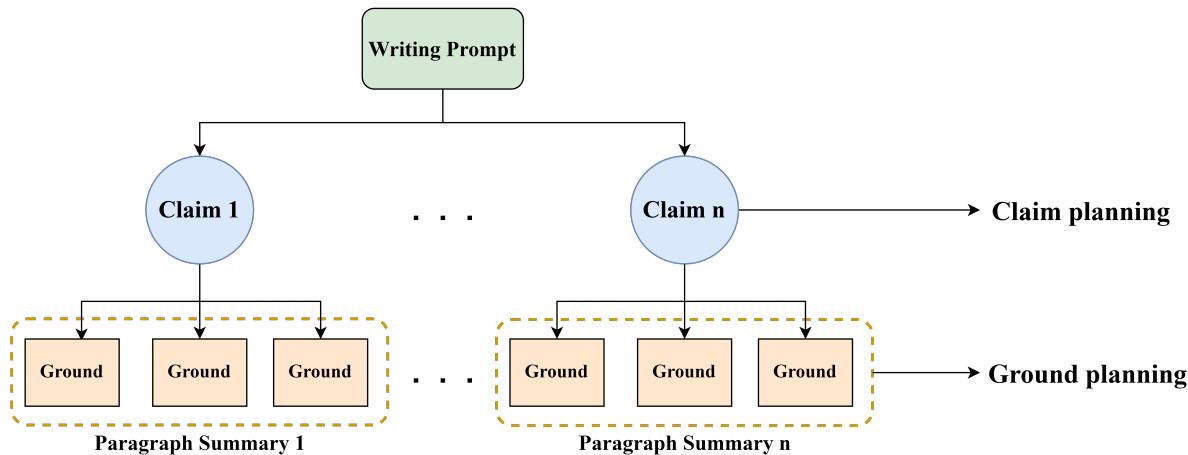

Proposed by Stephen Toulmin, this model suggests that a valid argument consists of several specific components. For the purpose of AI generation, the researchers simplified this into a hierarchical tree structure consisting of two main layers:

- Claims (The Abstract): These are the high-level assertions or positions the essay takes.

- Grounds (The Concrete): These are the specific data, evidence, warrants, or reasoning that support the claims.

Most AI models try to generate the essay (Claims + Grounds + Filler) all at once. The core idea of this paper is to force the AI to plan the Claims first, then plan the Grounds based on those claims, and only then write the essay.

As shown in Figure 4 above, a human-authored text naturally follows this structure. A prompt leads to major claims, which branch out into specific reasoning and examples. The goal of the PESA framework is to mimic this mental process.

The Core Method: PESA

The researchers developed a unified framework called PESA. It stands for Proof-Enhancement and Self-Annotation.

These two names correspond to the two biggest challenges in this field:

- Proof-Enhancement: How do we force the model to follow a logical structure?

- Self-Annotation: Where do we get the training data? (Standard datasets contain essays, but they don’t have the “Claims” and “Grounds” separately labeled).

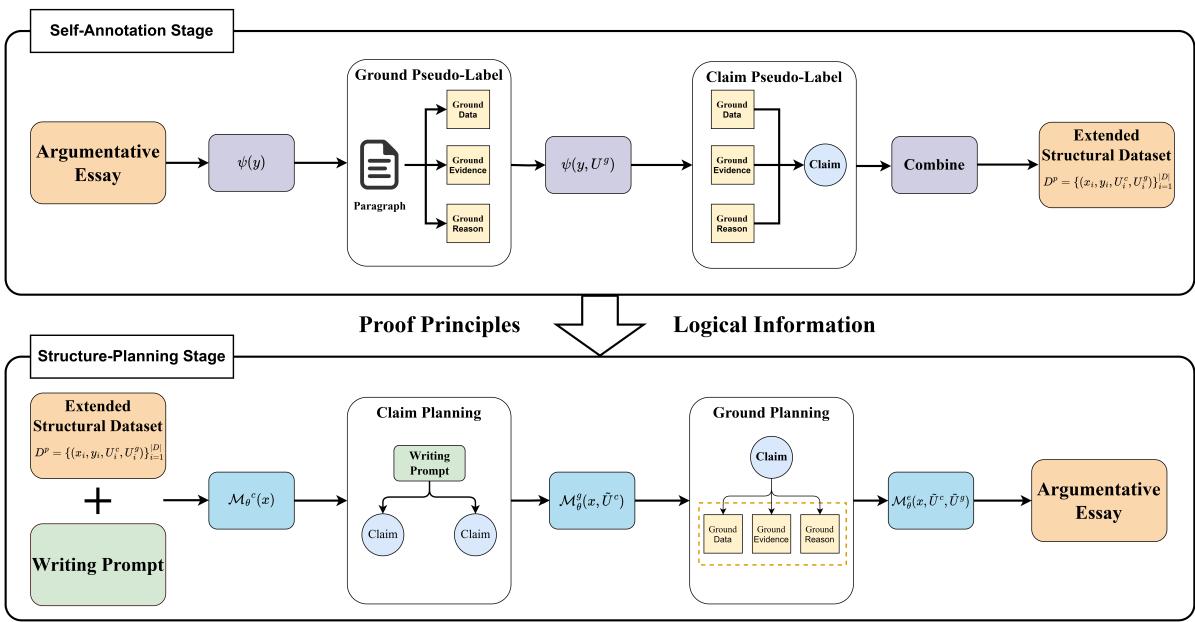

Let’s look at the full architecture of the system:

The framework operates in a cycle. The bottom half of the image represents the data preparation (Self-Annotation), and the top half represents the actual generation process (Proof-Enhancement). Let’s break these down.

Stage 1: Self-Annotation (The Data Problem)

Training a model to generate “Claims” and “Grounds” requires a dataset where essays are already split into these components. Since such a dataset is expensive to create manually, the researchers used a technique called Self-Annotation.

They utilized a powerful LLM (GPT-4) to “reverse engineer” existing high-quality essays. It works like a text summarization task but in reverse order of the writing process:

- Extracting Grounds (\(U^g\)): The model reads a paragraph of a human-written essay (\(Y\)) and summarizes the specific evidence and reasoning.

- Extracting Claims (\(U^c\)): The model reads the extracted grounds and the essay to summarize the main point (the Major Claim).

This is formalized mathematically as:

\[ \begin{array} { l } { { U ^ { g } = \psi ( y ) , } } \\ { { U ^ { c } = \psi ( y , U ^ { g } ) , } } \end{array} \]Here, \(\psi\) represents the LLM-based extraction function. This process turns a standard dataset of essays into a “pseudo-labeled” dataset containing the Prompt (\(X\)), the Claim Plan (\(U^c\)), the Ground Plan (\(U^g\)), and the final Essay (\(Y\)).

Stage 2: Proof-Enhancement (The Generation Process)

Once the model is trained on this structured data, it can generate new essays using a three-step Tree Planning Approach. This hierarchy ensures that the logic flows top-down, preventing the “rambling” nature of standard language models.

Step 1: Claim Planning

First, the model (\(\mathcal{M}^c\)) looks at the writing prompt (\(x\)) and generates the major claims (\(U^c\)). This acts as the skeleton of the essay. It decides the stance and the main arguments without getting bogged down in details.

\[ \tilde { U } ^ { c } = { \mathcal { M } } _ { \theta } { } ^ { c } ( x ) . \]Step 2: Ground Planning

Next, a second model (\(\mathcal{M}^g\)) takes the prompt (\(x\)) AND the just-generated claims (\(U^c\)) to generate the grounds (\(U^g\)). This fills in the skeleton with muscle—evidence, data, and reasoning that directly support the claims.

\[ { \tilde { U } } ^ { g } = { \mathcal { M } } _ { \theta } ^ { g } ( x , { \tilde { U } } ^ { c } ) . \]Step 3: Essay Generation

Finally, the generation model (\(\mathcal{M}^e\)) takes the prompt, the claims, and the grounds to write the final essay (\(y\)). Because the logic and evidence are already planned out, the model essentially just needs to “connect the dots” with fluent language.

\[ \tilde { y } = \mathcal { M } _ { \theta } ^ { e } ( x , \tilde { U } ^ { c } , \tilde { U } ^ { g } ) . \]Training the Model

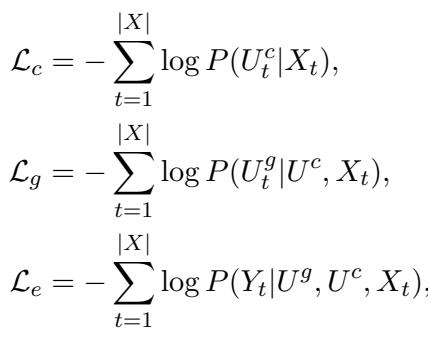

The system is trained using distinct loss functions for each stage. This ensures that the model learns to be a good planner just as much as it learns to be a good writer.

- \(\mathcal{L}_c\): Penalizes the model if the Claims don’t match the training data.

- \(\mathcal{L}_g\): Penalizes the model if the Grounds don’t match (given the Claims).

- \(\mathcal{L}_e\): Penalizes the model if the final Essay doesn’t match (given the Claims and Grounds).

Experiments and Results

The researchers evaluated PESA on the ArgEssay dataset, which contains over 11,000 essays on topics from exams like IELTS and TOEFL. They compared PESA against several strong baselines, including LLaMA-2 (fine-tuned) and previous state-of-the-art planning models like DD-KW (Dual Decoder with Keywords).

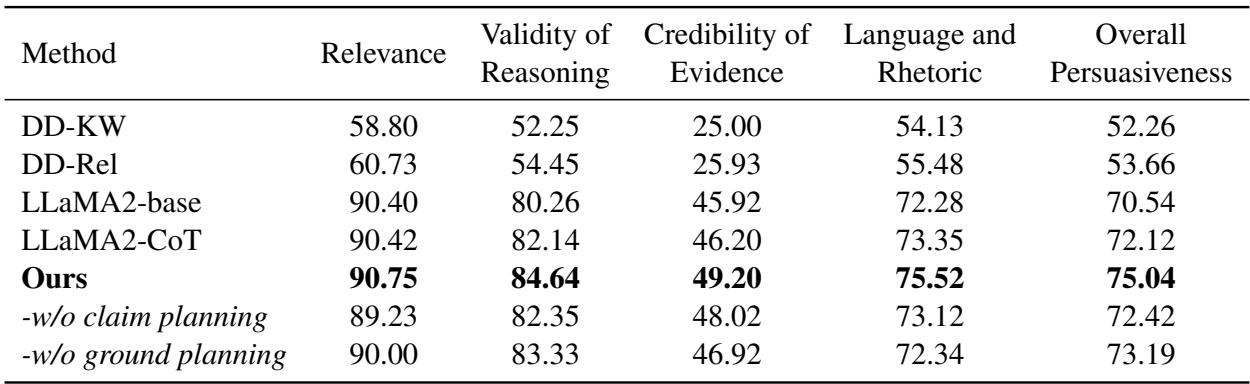

Automatic Evaluation

Since evaluating essay quality automatically is difficult, the researchers used GPT-4 as a judge, asking it to score essays based on Relevance, Validity of Reasoning, and Credibility of Evidence.

Note: The table above displays the automatic evaluation results.

The results were impressive. PESA (labeled “Ours”) outperformed all baselines.

- Validity of Reasoning: PESA achieved a score of 84.64, significantly higher than the standard LLaMA2-base (80.26).

- Credibility of Evidence: PESA scored 49.20, beating the closest competitor.

This confirms that explicitly planning the “Claims” and “Grounds” helps the model stick to a logical path.

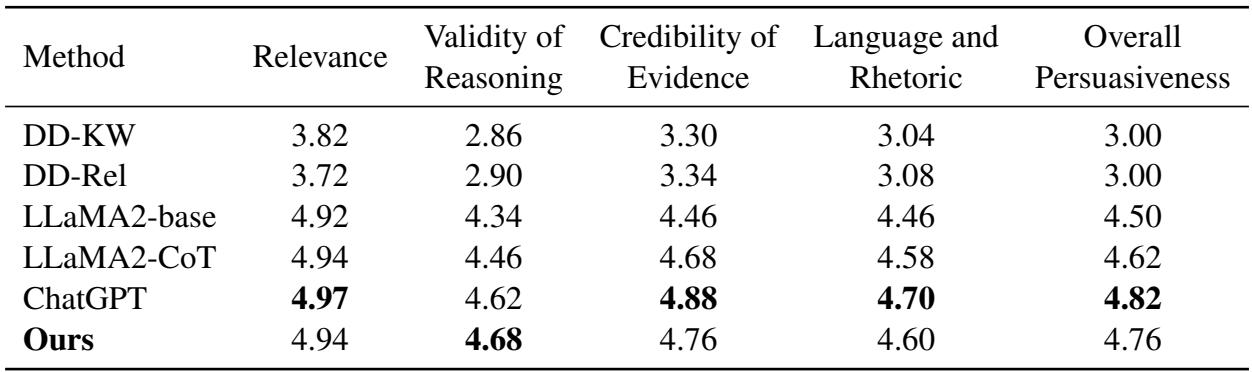

Human Evaluation

Automatic metrics are useful, but human judgment is the gold standard for writing. The researchers hired evaluators to compare PESA against the baselines and even ChatGPT.

As seen in the table above, PESA achieved a score of 4.76 in Overall Persuasiveness, nearly matching ChatGPT (4.82). This is a remarkable feat considering PESA is based on LLaMA-13B, which is a significantly smaller model than the massive architecture behind ChatGPT.

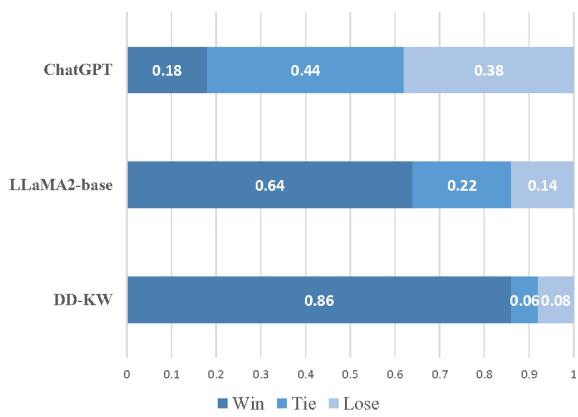

The researchers also conducted a “Head-to-Head” win rate analysis:

When pitted directly against other models:

- PESA won against DD-KW (the previous specific AEG method) 86% of the time.

- PESA won against LLaMA-2-base 64% of the time.

- Against ChatGPT, PESA managed to achieve a Tie or Win in about 62% of cases, proving it is highly competitive.

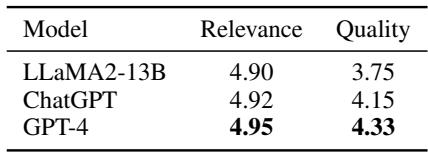

Does the “Self-Annotation” actually work?

A critic might ask: “Is the data generated by GPT-4 actually good enough to train on?” The researchers analyzed this by having humans rate the quality of the pseudo-labels (the extracted claims and grounds).

The data shows that GPT-4 (used for the final method) produces highly relevant and high-quality planning data (4.95/5 for relevance). This validates the strategy of using a stronger model to “teach” a smaller model how to structure its thoughts.

Conclusion & Implications

The PESA framework represents a significant step forward in Natural Language Generation. It moves us away from “black box” generation—where we hope the model gets the logic right—toward a structured, transparent process.

By integrating the Toulmin Argumentation Model, the researchers successfully taught an AI to:

- Plan its major arguments (Claims).

- Substantiate those arguments with evidence (Grounds).

- Write a coherent essay based on that plan.

The most exciting takeaway is that logic can be decoupled from size. You don’t necessarily need a trillion-parameter model to write persuasive essays. You need a model that understands the structure of persuasion. By explicitly modeling the proof process, a smaller model (LLaMA-13B) was able to punch above its weight class, delivering results comparable to ChatGPT.

For students and researchers in AI, this highlights the importance of inductive bias—designing model architectures that reflect the underlying structure of the problem (in this case, the hierarchical nature of arguments) rather than relying solely on massive amounts of unstructured data.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2410.22642/images/cover.png)