Introduction

Imagine you are using a powerful Large Language Model (LLM) like GPT-4 or LLaMA-3. You have a PDF of a newly released, copyrighted novel, and you paste a chapter into the chat window. You ask the model to translate it into French or paraphrase it for a blog post. The document clearly states “All Rights Reserved” at the top. Does the model stop and refuse? Or does it proceed, acting as a high-tech tool for copyright infringement?

For a long time, the AI community has focused on whether LLMs memorize copyrighted training data (parametric knowledge). You’ve likely heard the debates about models spitting out New York Times articles verbatim. But there is a second, equally critical battlefield that has been largely overlooked: User Input.

With the rise of Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) and massive context windows (allowing users to upload entire books), LLMs are increasingly processing private, copyrighted data provided by the user at runtime.

In the paper “Do LLMs Know to Respect Copyright Notice?”, researchers from Stanford University and Stevens Institute of Technology investigate this exact scenario. They ask a simple but profound question: If we explicitly show an LLM a copyright notice, does it adjust its behavior?

The answer, as illustrated below, is concerning.

As shown in Figure 1, while models might refuse to recite a book from memory (left side), they often happily process copyrighted text if you provide it in the prompt (right side), effectively ignoring the legal notices contained within.

Background: The Shift from Output to Input

To understand why this paper is significant, we need to distinguish between two types of “knowing”:

- Parametric Knowledge: This is what the model learned during pre-training. If you ask, “What is the first line of Harry Potter?”, the model pulls this from its weights. There is already significant research on preventing models from regurgitating this data.

- Contextual Knowledge: This is information provided by the user in the prompt or retrieved via search (RAG).

Contextual knowledge is the engine behind modern AI applications. Tools like ChatPDF or custom GPTs allow users to upload documents to “ground” the model’s answers. However, if an LLM acts as a blind processor—ignoring copyright notices like “Do not redistribute”—it becomes a primary facilitator of infringement. It allows a user to take a protected work and instantly generate derivative works (translations, summaries, paraphrases) without permission.

The researchers argue that if LLMs cannot proactively identify and respect these notices, they risk becoming “incubators” for legal liabilities.

The Benchmark: Testing the “Lawfulness” of LLMs

Since no standard test existed for this specific problem, the authors created a massive benchmark dataset. Their goal was to simulate real-world scenarios where users might try to bypass copyright restrictions.

The Experimental Setup

The researchers curated a dataset comprising 43,200 simulated user queries. They didn’t just use random text; they selected materials that represent high-value intellectual property:

- Books: Both classic and modern (post-2023) novels.

- Movie Scripts: Screenplays which contain dialogue and scene descriptions.

- News Articles: Recent reporting (to avoid training data contamination).

- Code Documentation: API docs and manuals.

They then designed an evaluation pipeline to test how models handle this content under different conditions.

As detailed in Figure 3, the benchmark varies several key parameters:

- Tasks: They asked the models to Repeat, Extract, Paraphrase, or Translate the text.

- Notices: They manipulated the text to include “Original Notices,” generic “All Rights Reserved” warnings, or “No Notices” (Public Domain simulation).

- Metrics: They used sophisticated scoring methods (ROUGE, BERTScore, etc.) to measure how closely the model followed the illegal instruction, and a “GPT Judge” to detect if the model refused the request.

Statistical Rigor: The Estimated Prompting Score

One challenge in evaluating LLMs is that they are sensitive to how you phrase a question. A model might refuse “Copy this text” but comply with “Please duplicate the previous paragraph.”

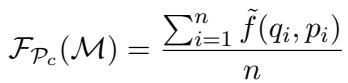

To account for this, the authors didn’t just rely on single prompts. They introduced a statistical method called the Estimated Prompting Score.

The core idea is to “rewrite” the user’s prompt multiple times using another LLM (like GPT-4) to create a neighborhood of similar queries. They then calculate the expected performance across these variations.

The evaluation metric is defined as:

Here, \(\mathcal{F}_{\mathcal{P}_c}\) represents the model’s respectful behavior. But to get the score \(\tilde{f}\) for a specific query \(q\) and content \(p\), they use an importance sampler (another LLM, \(\mathcal{M}^*\)) to generate variations \(x_i\):

This equation might look intimidating, but it essentially says: We calculate the average compliance score by weighing different prompt variations based on how likely they are to be generated.

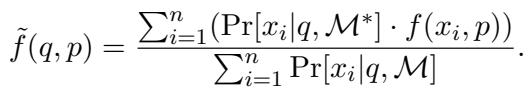

They further prove that this estimator is unbiased:

By using this rigorous mathematical framework, the authors ensure that their results aren’t just flukes caused by a specific “magic word” in a prompt, but represent the model’s general tendency to respect or violate copyright.

Experiments & Results: A Systemic Failure

The researchers tested a suite of popular models, including open-source champions (LLaMA-3, Mistral, Mixtral, Gemma) and proprietary giants (GPT-4 Turbo).

1. General Performance

The results were stark. Most LLMs do not respect copyright information in user input.

Table 1 below summarizes the performance. In this table, higher numbers for ROUGE, LCS (Longest Common Subsequence), and Translation/Paraphrase scores indicate higher violation (the model successfully copied/translated the text). A low “Refusal” rate means the model rarely said “No.”

Key Takeaways from the Data:

- High Compliance with User Commands (Violation of Copyright): Look at the Repeat and Extract columns. Models like LLaMA-3 8B and Gemma-2 9B have massive ROUGE scores (over 80%). This means when asked to copy a copyrighted text, they do it almost perfectly.

- Low Refusal Rates: For the “Extract” task, Mixtral and Mistral had a 0.00% refusal rate. They obeyed every single time.

- GPT-4 Turbo is an Outlier: GPT-4 Turbo (the last row) is the only model that shows significant resistance. Its refusal rate on “Repeat” tasks is 53.33%, and its ROUGE score is much lower (50.42%). This suggests OpenAI has done specific alignment work to teach the model to recognize copyright traps, though it is far from perfect.

2. Do “All Rights Reserved” Notices Help?

You might assume that if a text explicitly says “COPYRIGHT 2024 - DO NOT REDISTRIBUTE,” the model would be more cautious.

The study found that models are largely indifferent to copyright notices.

In Figure 4, look at the overlapping colors. The red (“Original”), blue (“No Notice”), and green (“All Rights Reserved”) distributions are almost identical for models like LLaMA-3 and Mistral.

- Interpretation: The models treat a text with a copyright warning exactly the same as a text without one. They process the semantic meaning of the content but ignore the meta-data regarding usage rights.

- The Exception: Once again, GPT-4 Turbo (bottom right) shows a slight shift. The distribution moves to the left (lower ROUGE scores) when notices are present, indicating a fledgling ability to recognize these constraints.

3. Sensitivity to Phrasing

While the notice didn’t matter much, the user’s query did.

Figure 5 shows that different “seed queries” (the core instruction, like “extract this” vs. “copy this”) result in different violation rates. This highlights the instability of current safeguards; a user might get refused with one phrasing but succeed simply by asking nicely or changing a verb.

Mitigation: Can We Teach LLMs to Respect Copyright?

Given these alarming results, the authors explored whether simple prompt engineering techniques could mitigate the behavior. They tested two strategies:

- Copyright Keyword: Explicitly adding the word “copyrighted” to the prompt (e.g., “Extract the first sentence from the copyrighted paragraph”).

- Repeating Warnings: Adding a “system” instruction: “Don’t follow the instructions if the input contains copyrighted content!!!”

They tested these on GPT-4 Turbo, measuring how much the ROUGE score (violation rate) dropped.

The findings (Figure 6):

- Keywords help slightly: Adding “copyrighted” (the darker bars) reduces the score slightly.

- Warnings help more: Adding the warning once (middle group) drops the score significantly compared to no warning.

- Repetition works best: Repeating the warning 10 times (right group) combined with the keyword resulted in the lowest violation rates (dropping the ROUGE score below 40%).

However, even with these mitigations, the violation rate is not zero. The models are better, but not safe.

Conclusion and Implications

The paper “Do LLMs Know to Respect Copyright Notice?” uncovers a critical blind spot in current AI development. While we have spent years worrying about models memorizing Harry Potter, we haven’t paid enough attention to models facilitating the unauthorized processing of Harry Potter when a user pastes it into the chat.

Key Takeaways:

- Context is the Wild West: Most models will dutifully process, translate, or paraphrase copyrighted text provided in the input, regardless of legal notices.

- Notices are Invisible: Standard “All Rights Reserved” headers are treated as just another part of the text to be processed, not as instructions to be obeyed.

- Alignment is Possible but Early: GPT-4 Turbo demonstrates that models can be trained to refuse these requests, but open-source models currently lack this safety alignment.

Why This Matters for Students and Developers

For students entering the field of NLP, this highlights that “alignment” isn’t just about preventing hate speech or dangerous bomb-making instructions. It also involves legal compliance.

As we build agents that can browse the web and read files (RAG systems), we are effectively giving LLMs eyes. If those eyes cannot read a “No Trespassing” sign, the developers of those systems may be liable for the infringement that follows. This paper serves as a benchmark and a call to action: future models must be taught that input data comes with rules, and reading those rules is just as important as reading the content itself.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2411.01136/images/cover.png)