The intersection of Artificial Intelligence and medicine is currently one of the most exciting frontiers in technology. Every few months, we see a new headline announcing a “Medical LLM”—a specialized artificial intelligence tailored specifically for healthcare. The narrative is almost always the same: take a powerful general-purpose model (like Llama or Mistral), train it further on a massive library of medical textbooks and PubMed articles, and voilà: you have a digital doctor that outperforms its generalist predecessor.

This process is known as Domain-Adaptive Pretraining (DAPT). Theoretically, it makes perfect sense. If you want a human to be a doctor, you send them to medical school. You don’t just rely on their high school education.

However, a critical new research paper titled “Medical Adaptation of Large Language and Vision-Language Models: Are We Making Progress?” challenges this fundamental assumption. The researchers from Carnegie Mellon University, Mistral AI, Johns Hopkins, and Abridge AI conducted a rigorous, “apples-to-apples” comparison of medical models against their general-purpose base models.

Their conclusion? Most “medical” models do not statistically outperform the general models they were built on.

In this deep dive, we will explore why the industry might be overestimating the value of medical specialization, the flaws in current evaluation methods, and how prompt engineering plays a pivotal role in revealing the truth.

The Standard Recipe: Domain-Adaptive Pretraining (DAPT)

Before we dissect the paper’s critique, we need to understand the status quo. The standard recipe for creating a medical AI model involves two main stages:

- General Pretraining: A model is trained on a massive, diverse dataset (the “common crawl” of the internet) to learn language, reasoning, and general world knowledge. This results in a “Base Model” (e.g., Llama-2-70B).

- Continued Pretraining (DAPT): That base model is then subjected to further training, exclusively on biomedical corpora like PubMed articles, clinical guidelines, and medical textbooks. This results in a “Medical Model” (e.g., Meditron-70B).

The assumption is that this second step injects domain-specific knowledge that the base model lacks, leading to superior performance on tasks like the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE).

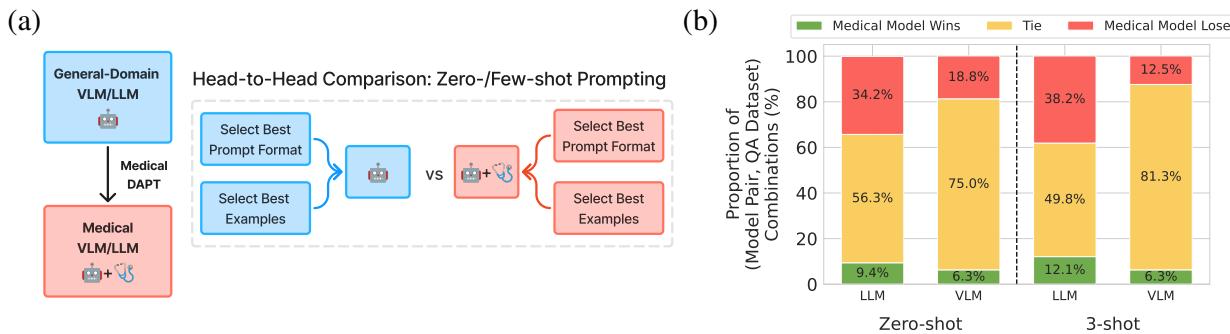

The researchers noticed a problem, however. When new medical models are released, they are often compared against baselines in unfair ways. They might be compared to older models, smaller models, or models using different prompting strategies. This paper seeks to fix that by establishing a Head-to-Head comparison.

As shown in Figure 1 above, the methodology is straightforward but rigorous: take a base model and its exact medical descendant, and evaluate them under identical conditions to see if the medical training actually helped.

The Evaluation Trap: Why Prompts Matter

To understand why previous claims of superiority might be exaggerated, we have to talk about prompt sensitivity.

Large Language Models (LLMs) are notoriously sensitive to how you ask a question. Changing a prompt from “Answer the following:” to “Please select the correct option:” can sometimes drastically change the accuracy of the output. Crucially, the “best” prompt format for Model A is rarely the best prompt format for Model B.

If a researcher releases a new Medical Model, they naturally spend time finding the best prompt to make their model shine. If they then use that exact same prompt to test the Base Model, the Base Model is at a disadvantage. It’s like testing a French speaker and a Spanish speaker on their math skills, but giving the test in French.

The Solution: Model-Specific Prompt Optimization

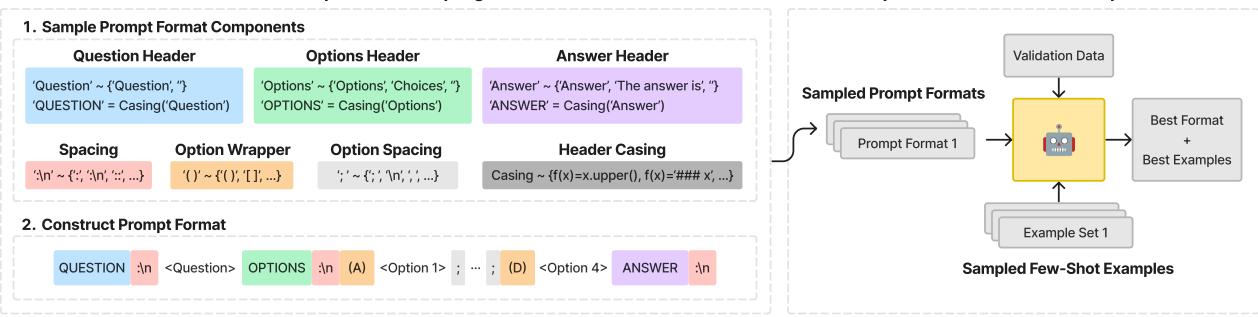

To ensure a fair fight, the authors of this paper treated the prompt format as a hyperparameter. They didn’t just pick one prompt; they engineered a method to find the best possible prompt for every single model independently.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the researchers utilized a Context-Free Grammar (CFG) to define a massive search space of possible prompt formats. They varied:

- Headers: “Question:”, “### Question”, “Input:”

- Choice Formatting: “(A)”, “[A]”, “A.”

- Separators: Newlines, spaces, dashes.

For every model (both General and Medical), they sampled different prompt formats and paired them with different sets of “Few-Shot” examples (example questions and answers provided in the context to help the model understand the task). They ran these combinations against a validation set to select the optimal strategy for that specific model before running the final test.

This ensures that if the Medical Model wins, it wins because it has better knowledge, not because the prompt happened to fit its training data better.

The Core Experiment

The researchers evaluated 7 Medical LLMs and 2 Medical Vision-Language Models (VLMs) against their general-domain counterparts.

The Lineup

The comparisons included heavy hitters in the open-source space:

- Llama-2 & Llama-3 vs. Meditron, OpenBioLLM, & Clinical-Camel

- Mistral vs. BioMistral

- LLaVA (Vision) vs. LLaVA-Med

They tested these models on standard medical benchmarks, including MedQA (based on the USMLE), PubMedQA, and various medical subsets of the MMLU benchmark.

Accounting for Uncertainty

In standard machine learning papers, if Model A scores 80.5% and Model B scores 80.2%, Model A is declared the winner. However, on smaller datasets common in medicine, this difference might be statistical noise.

The authors used bootstrapping—a statistical resampling technique—to calculate 95% confidence intervals. If the performance intervals of the two models overlapped, the result was declared a “Tie.” A “Win” was only recorded if the Medical Model was statistically significantly better than the Base Model.

Finding 1: The Disappointment

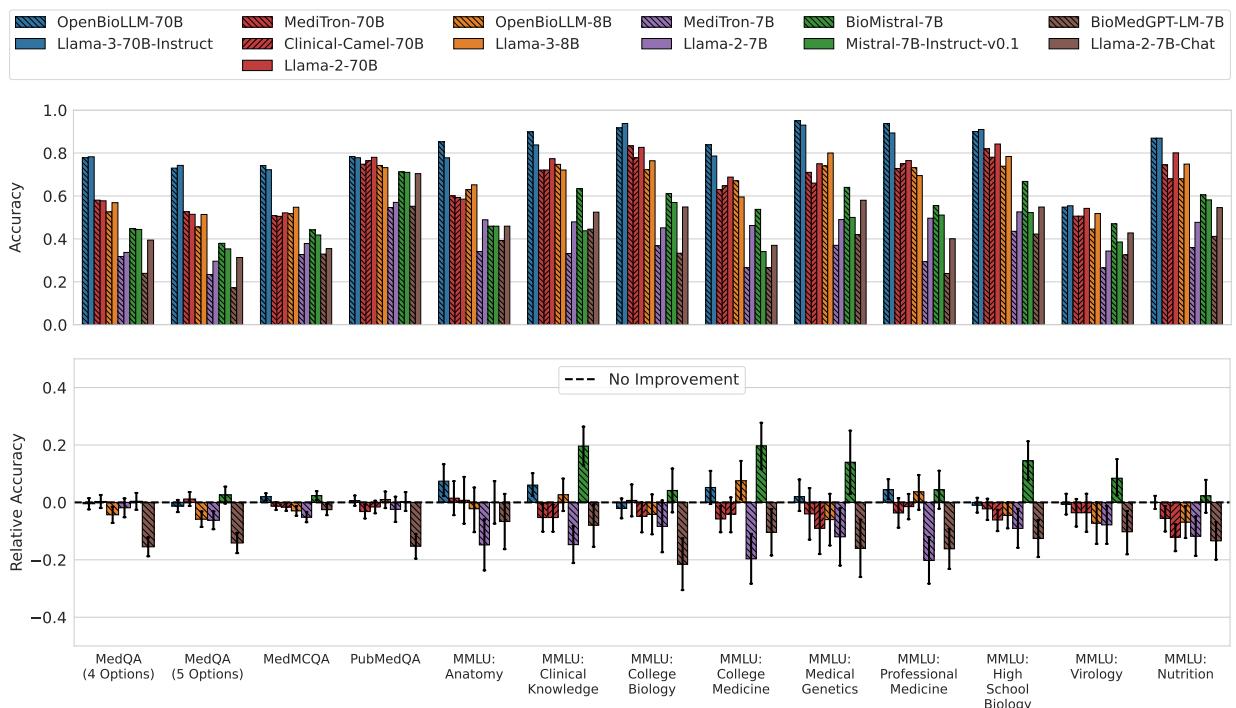

When the playing field was leveled using optimized prompts and statistical rigor, the results were startling.

For Large Language Models (LLMs): Most medical models failed to consistently outperform their base models. In the vast majority of cases, the result was a statistical tie.

Look at the bottom row of Figure 3 (Relative Accuracy). The zero-line represents “No Improvement.” You can see that for almost every model pair (grouped by color patterns), the error bars cross the zero line.

- OpenBioLLM-70B and BioMistral-7B were the only ones to show statistically significant improvements, but even then, not across all datasets.

- Some models, like Meditron-7B and BioMedGPT, actually performed significantly worse than the general models they were based on (indicated by the bars dipping into the negative).

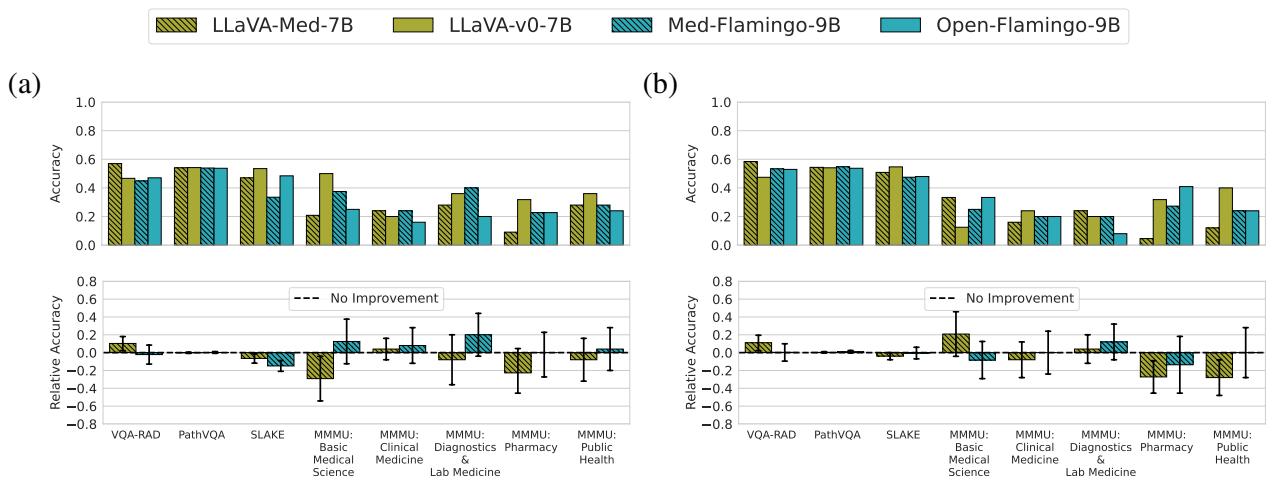

For Vision-Language Models (VLMs): The story was even bleaker for multimodal models.

Figure 4 shows that LLaVA-Med and Med-Flamingo (the red bars in Figure 1a) are virtually indistinguishable from LLaVA and Open-Flamingo (the blue bars). The relative accuracy hovers almost perfectly at zero. This suggests that the additional training on biomedical image-text pairs did almost nothing to improve the models’ ability to answer visual questions about radiology or pathology in a zero/few-shot setting.

Finding 2: The Illusion of Progress

If the results are this flat, why do so many papers claim state-of-the-art performance for their medical models?

The authors performed an ablation study to replicate the “standard” (flawed) evaluation method. They took the best prompt found for the Medical Model and forced the Base Model to use it. They also removed the statistical significance testing, looking only at raw averages.

The results of this simulation were dramatic.

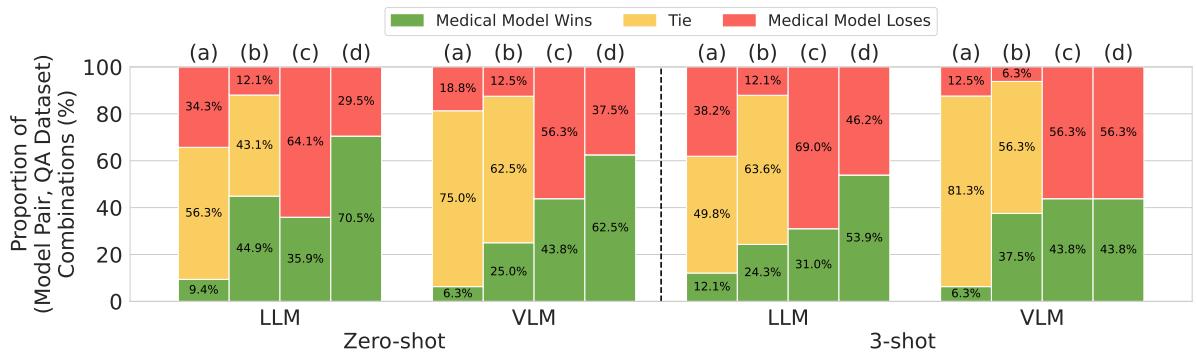

Figure 5 visualizes this distortion perfectly:

- Column (a) represents the rigorous method: Very few wins (green), mostly ties (yellow).

- Column (d) represents the flawed, common method: Massive domination by medical models (green).

In the Zero-shot setting for LLMs, using the flawed methodology makes it look like Medical Models win 70.5% of the time. When you correct the methodology (optimizing prompts for everyone), the win rate drops to just 9.4%.

This proves that much of the “progress” reported in medical AI literature may simply be an artifact of prompt sensitivity. The medical training adapted the model to a specific style of prompting, but it didn’t necessarily increase the underlying medical knowledge or reasoning capability.

Why is this happening?

Why doesn’t training on medical textbooks help? The authors suggest a simple but profound explanation: General-domain models are already medically trained.

Modern foundation models like Llama-3 or GPT-4 are trained on datasets so vast (trillions of tokens) that they likely encompass the entirety of PubMed, Wikipedia Medicine, and open-access medical textbooks already.

When researchers perform DAPT (Domain-Adaptive Pretraining), they might just be showing the model data it has already seen. This is akin to a medical student re-reading a textbook they already memorized; it doesn’t add new information, it just reinforces existing pathways.

Furthermore, the “General” models are trained on diverse logic puzzles, code, and literature, which may foster strong reasoning capabilities that are critical for medical diagnosis—capabilities that might degrade if the model is over-trained on narrow medical text (a phenomenon known as “catastrophic forgetting,” though the authors note that most models simply tied rather than lost capability).

Conclusion: Are We Making Progress?

The paper’s title asks, “Are We Making Progress?” The answer is nuanced.

We are making progress in the sense that base models are becoming incredibly capable at medical tasks. However, the specific technique of Domain-Adaptive Pretraining (DAPT) for open-source models seems to yield diminishing returns for Question-Answering tasks.

For students and practitioners in AI, the takeaways are clear:

- Don’t Trust the Average: A raw accuracy score means nothing without context. Always ask if the comparison was fair and if the difference is statistically significant.

- Respect the Prompt: A model is only as good as its prompt. Comparing models using a fixed prompt is scientifically invalid.

- Generalists are Powerful: Do not underestimate off-the-shelf general models. Llama-3-70B or GPT-4 often rival or beat specialized models simply because their fundamental reasoning engines are stronger.

While there is certainly a place for medical AI—perhaps in interpreting complex clinical notes, handling private patient data securely, or specific fine-tuning tasks—the era of simply “training on PubMed” to get a better doctor appears to be closing. Future progress will likely require more novel approaches than simple domain adaptation.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2411.04118/images/cover.png)