Introduction

We live in an era of information explosion. Every day, news outlets, social media, and forums are flooded with claims about company performance. “Company X increased its revenue by 20%,” or “Company Y’s debt load has doubled.” For investors and analysts, the stakes of acting on false information are incredibly high. The antidote to misinformation is verification—checking these claims against the original source documents, such as 10-K (annual) and 10-Q (quarterly) reports filed with the SEC.

However, automating this verification process is notoriously difficult. Financial documents are not merely long text files; they are dense, hybrid ecosystems containing complex tables and nuaced legal language. While Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 have shown impressive capabilities in general tasks, their ability to act as financial auditors remains an open question.

This brings us to FINDVER, a new benchmark developed by researchers at Yale NLP. FINDVER is designed to rigorously test whether LLMs can verify claims within long, hybrid-content financial documents and—crucially—whether they can explain their reasoning.

In this deep dive, we will explore why financial verification is so challenging, how the FINDVER benchmark was constructed using financial experts, and what the results tell us about the current gap between human experts and Artificial Intelligence.

The Background: Why Current Benchmarks Fall Short

To understand the contribution of FINDVER, we must first look at the landscape of automated fact-checking. Claim verification is a well-established field in Natural Language Processing (NLP). Typically, a model is given a claim and a piece of evidence, and it must decide if the evidence entails (supports) or refutes the claim.

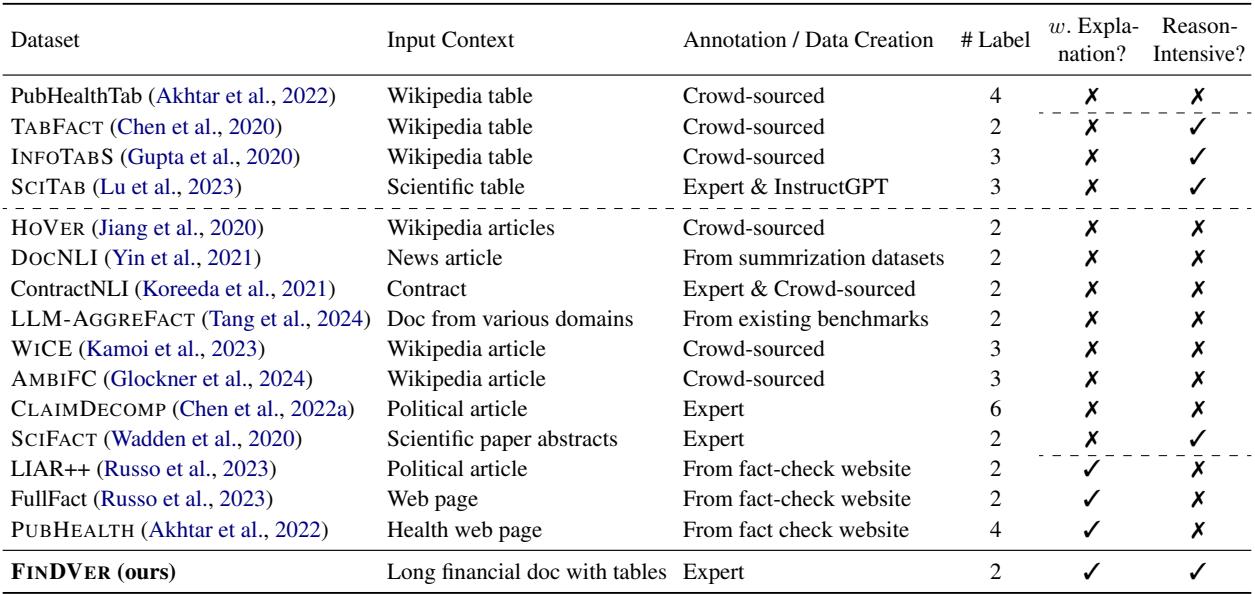

However, existing benchmarks have significant limitations when applied to the financial domain. Most datasets rely on Wikipedia articles or simple, isolated tables. They rarely demand that a model digest a 100-page document containing mixed text and tabular data to perform complex arithmetic. Furthermore, most previous benchmarks only ask for a simple “True/False” label. In finance, where decisions must be defensible, a label without an explanation is useless.

The table below highlights the gap that FINDVER fills:

As shown in the comparison above, FINDVER stands out for four reasons:

- Expert Annotation: Data is created by finance professionals, not crowdsourced workers.

- Complex Document Comprehension: It uses full financial filings requiring the synthesis of text and tables.

- Reasoning-Process Explanation: Models must explain how they reached a conclusion.

- Diverse Reasoning: It tests information extraction, numerical calculation, and domain knowledge.

Core Method: Building a Financial Truth Serum

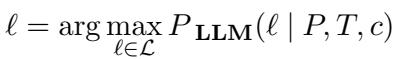

The researchers defined the task formally to ensure clarity. Given a financial document \(d\) (containing text paragraphs \(P\) and tables \(T\)) and a claim \(c\), the model must perform two sub-tasks.

First, Entailment Classification. The model must maximize the probability of selecting the correct label \(\ell\) (either “entailed” or “refuted”):

Second, and perhaps more importantly, Explanation Generation. The model must generate a natural language explanation \(e\) that outlines the reasoning steps taken to verify the claim:

The Challenge of Hybrid Content

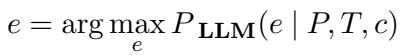

Why is this hard? Consider the following example from the benchmark. To verify a claim about customer accounts, a model cannot simply perform a keyword search. It must locate specific numbers embedded in a “Sources and Uses of Cash” section and cross-reference them with a cash flow table from a different fiscal year.

In the example above (Figure 1), the model has to locate data points across different modalities (text and tables), understand the fiscal periods (March 31, 2023 vs. 2024), and perform a calculation. This is the Numerical Reasoning aspect of FINDVER.

Constructing the Dataset: A Pipeline of Experts

One of the strongest critiques of many NLP datasets is “garbage in, garbage out.” If the ground truth data is noisy, the evaluation is meaningless. To counter this, the FINDVER team utilized a rigorous pipeline involving financial experts (individuals with finance backgrounds, including CFA holders).

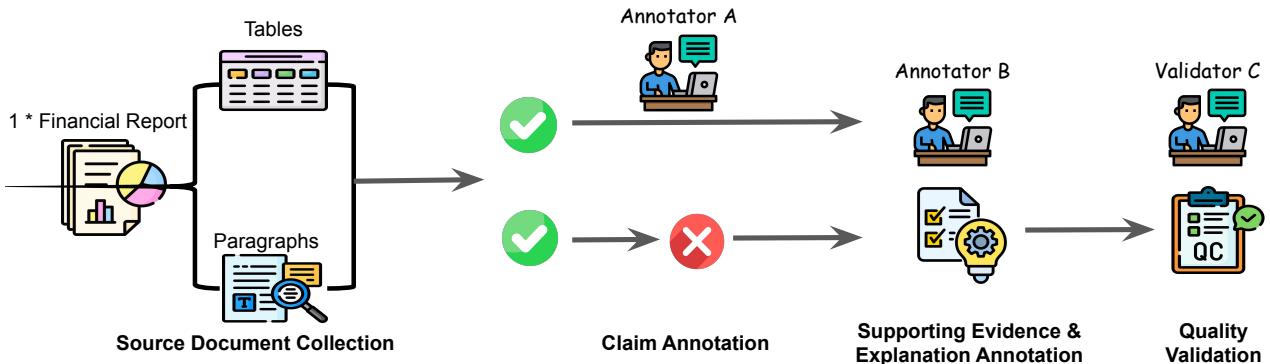

The pipeline, illustrated in Figure 2, follows these steps:

- Source Collection: They collected 523 actual quarterly and annual reports (Forms 10-Q and 10-K) released between January and April 2024. This date range is crucial because it ensures the documents are likely outside the training data of models like GPT-4, preventing the model from simply reciting memorized facts.

- Entailed Claim Annotation: Experts read the documents and wrote claims that are true (“entailed”) based on the evidence. They also logged the specific evidence locations (paragraph and table indices).

- Refuted Claim Generation: This is a clever step. Instead of asking annotators to dream up fake claims (which can be easily detected by style), they asked experts to take the true claims and slightly “perturb” them to introduce factual errors. This creates high-quality “refuted” claims that look very similar to true ones.

- Explanation Annotation: A separate annotator writes the step-by-step reasoning.

- Quality Validation: A final expert validator reviews the work to ensure accuracy.

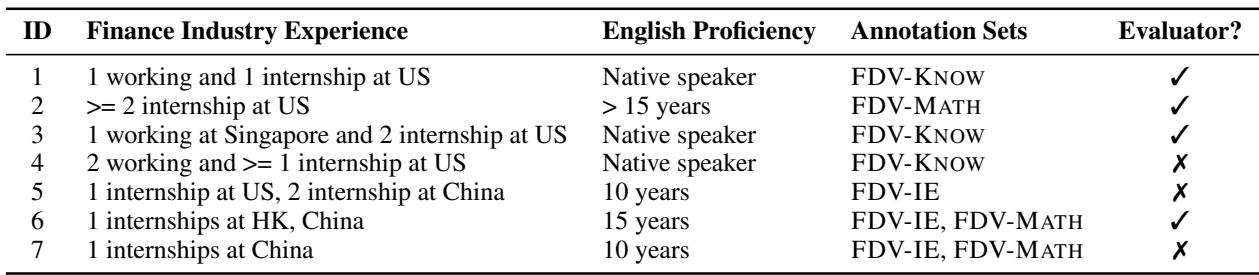

The involvement of experts is not a minor detail. Financial documents use specialized jargon that general crowdsourced workers often misunderstand. The profiles of the annotators confirm the high caliber of the data creators:

Three Types of Reasoning

The dataset is divided into three subsets to test different capabilities:

- FDV-IE (Information Extraction): Finding a needle in a haystack. Can the model retrieve a specific date, name, or figure from a 50-page document?

- FDV-MATH (Numerical Reasoning): Can the model perform calculations? For example, “Did the net interest expense decrease by 5%?” requires finding the numbers and doing the math.

- FDV-KNOW (Knowledge-Intensive): This requires external knowledge. For instance, understanding that a specific regulation mentioned in the text implies a certain financial obligation, even if not explicitly stated.

Below is an example of what a perfect “testmini” data point looks like. Note the clear “Explanation of Reasoning Process” which breaks the verification down into extraction and calculation steps.

Experiments and Results

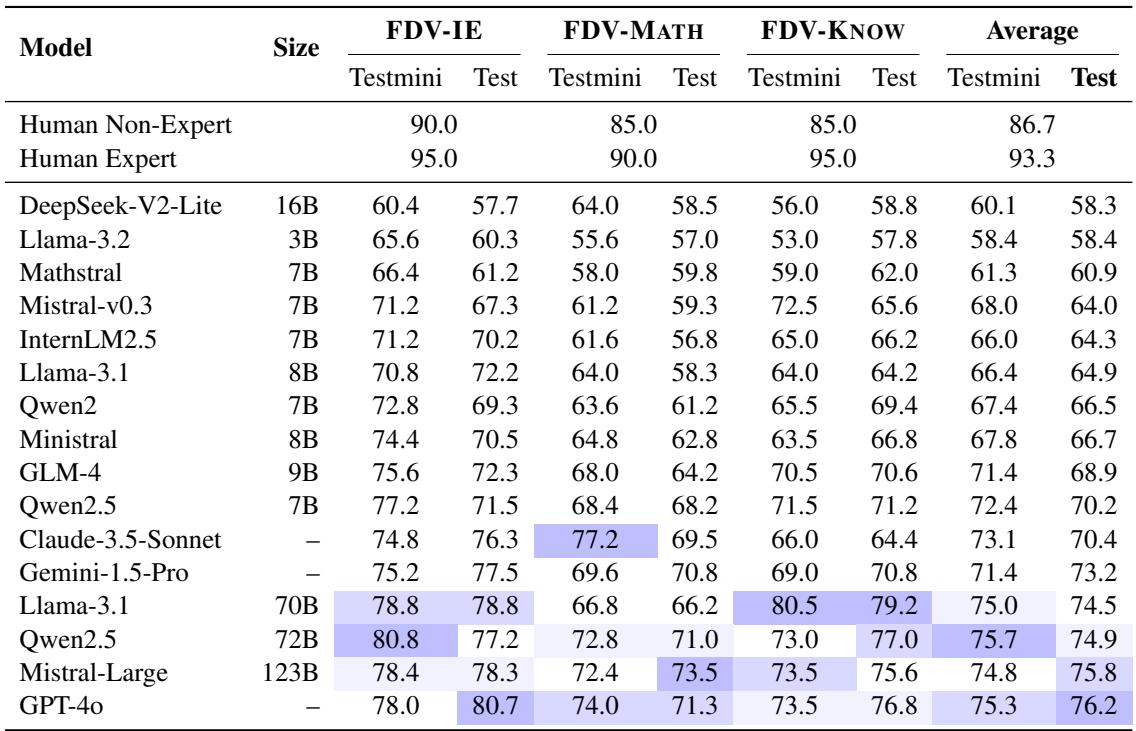

The researchers evaluated 16 different Large Language Models. This included proprietary models like GPT-4o, Claude-3.5-Sonnet, and Gemini-1.5-Pro, as well as open-source heavyweights like Llama-3, Qwen-2.5, and Mistral.

Because financial documents are so long (often exceeding 40,000 tokens), they tested two different strategies:

- Long-Context: Feeding the entire document into the model (for models that support massive context windows).

- RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation): Using a search algorithm to find the top 10 most relevant chunks of text/tables and feeding only those to the model.

The Headline Result: Humans are Still Superior

The most sobering result for AI enthusiasts is the performance gap. The researchers established a human baseline using both non-experts (CS undergrads) and experts (finance professionals).

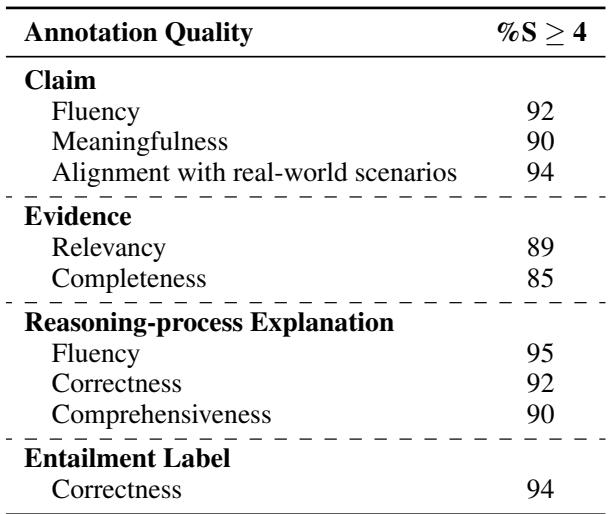

As shown in Table 3:

- Human Experts achieved 93.3% accuracy.

- GPT-4o, the best performing model, achieved only 76.2%.

- Open-source models like Qwen2.5-72B and Llama-3.1-70B are catching up, scoring around 74-75%.

This nearly 20% gap indicates that while LLMs are useful assistants, they are not yet ready to independently audit financial claims with expert-level reliability.

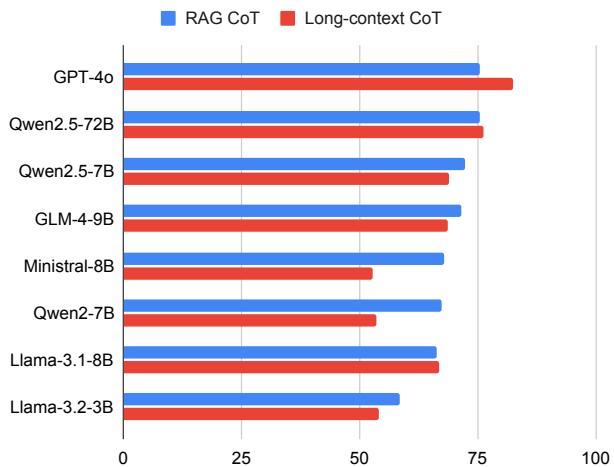

Strategy: Long-Context vs. RAG

A major debate in the AI community is whether we should dump all data into a model (Long-Context) or use search to find relevant bits (RAG).

Figure 3 reveals an interesting trend. For the most capable models (like GPT-4o), the Long-Context approach (red bars) slightly outperforms or matches RAG. This suggests these models are getting better at managing attention over massive sequences. However, for smaller or less capable models (like Llama-3.1-8B), RAG (blue bars) is often superior because it reduces the noise and focuses the model on the relevant section.

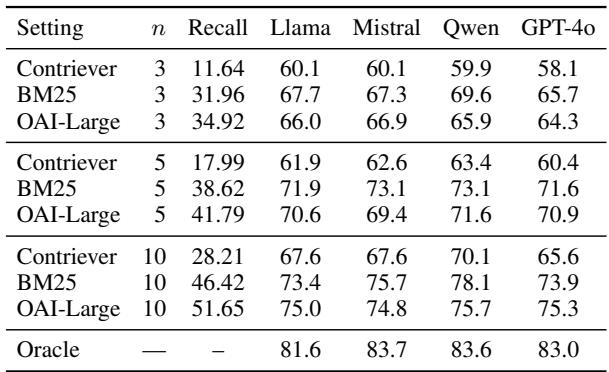

The Importance of Retrieval

If you choose the RAG route, the quality of your “search engine” matters immensely. The researchers tested different retrieval methods: BM25 (keyword matching), Contriever, and OpenAI’s embeddings.

Table 4 shows that Oracle performance (where the model is given the exact correct evidence) is significantly higher (around 83%) than any retrieval method. This proves that a major bottleneck is simply finding the right table or paragraph. Interestingly, the old-school BM25 algorithm often performed competitively with expensive vector embeddings, highlighting that in finance, exact keyword matching (like finding a specific account name) is vital.

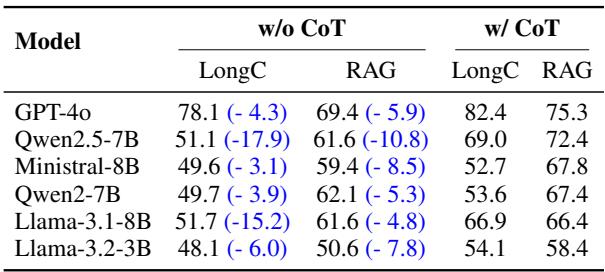

The Power of “Thinking”

Finally, the researchers validated the importance of Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting. This is the technique of asking the model to “think step-by-step” before giving a final answer.

Table 5 is definitive: removing the reasoning step (“w/o CoT”) causes accuracy to plummet. For example, Qwen2.5-7B drops from 69.0% to 51.1% in the Long-Context setting without CoT. This confirms that financial verification isn’t just about pattern matching; it requires logical, sequential deduction.

Error Analysis: Where do Models Fail?

Upon manually reviewing the errors made by GPT-4o, the researchers identified four main failure modes:

- Extraction Error: The model looks at the wrong table or paragraph.

- Numerical Reasoning Error: The model retrieves the correct numbers but sets up the math equation wrong (e.g., adding instead of subtracting).

- Calculation Error: The logic is right, but the arithmetic is wrong (a common issue with LLMs, though improving).

- Domain Knowledge Deficiency: The model fails to understand a financial accounting principle implicit in the text.

Conclusion and Implications

The FINDVER benchmark serves as a reality check for the deployment of AI in the financial sector. While models like GPT-4o and Claude-3.5 are impressive, they still lag significantly behind human experts when faced with the complexity of real-world financial filings.

The study highlights that future progress relies on three things:

- Better Retrieval: We need smarter systems that can pinpoint relevant tables in 100-page documents.

- Enhanced Reasoning: Models need to get better at multi-step numerical logic.

- Hybrid Literacy: The ability to seamlessly synthesize information from dense text and complex tables is non-negotiable.

For students and researchers entering the field, FINDVER offers a robust testing ground. It moves us away from verifying simple facts like “The sky is blue” toward verifying complex, high-stakes claims like “The company’s liquidity position improved due to operating cash flow offsets.” As models improve on FINDVER, we step closer to AI systems that can truly serve as reliable financial analysts.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2411.05764/images/cover.png)