Imagine trying to learn advanced quantum physics or organic chemistry, but every time a technical term like “electromagnetism” or “photosynthesis” comes up, your teacher stops speaking and slowly spells out the word, letter by letter. This is the reality for many Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing (DHH) students. While American Sign Language (ASL) is a rich and expressive language, it faces a significant bottleneck in STEM education: a lack of standardized signs for technical concepts.

When professional interpreters encounter these terms without a known sign, they resort to fingerspelling—using a manual alphabet to spell out English words. While functional, excessive fingerspelling creates a high cognitive load, forcing students to constantly switch between visual ASL and mental English processing. This creates a barrier to deep conceptual understanding.

In the research paper “ASL STEM Wiki: Dataset and Benchmark for Interpreting STEM Articles,” researchers from Microsoft Research, UC Berkeley, and the University of Maryland tackle this issue head-on. They introduce a massive new dataset and propose AI methodologies to help interpreters find and standardize signs, ultimately aiming to make STEM education more accessible.

The Problem: The STEM Sign Shortage

ASL is a living, evolving language. However, because Deaf individuals have historically been underrepresented in scientific fields, the growth of ASL vocabulary in STEM has lagged. While deaf scientists and educators do create signs for specific concepts, these signs often remain isolated within small circles and aren’t widely adopted.

In the absence of a standard sign, interpreters typically use one of three strategies:

- Translation by meaning: Using a sign for a related concept (e.g., using “intention” for “mathematical mean”), which can be confusing.

- Placeholder shorthands: Using an initialized handshape (like the letter ‘M’) which carries no inherent meaning.

- Fingerspelling: Spelling the word out (M-E-A-N).

The researchers note that fingerspelling is the most disruptive to learning when used excessively. To solve this, we need better tools to suggest standard signs to interpreters. But to build those tools, we first need data—lots of it.

Introducing ASL STEM Wiki

The core contribution of this paper is the ASL STEM Wiki dataset. It is the first continuous signing dataset specifically focused on Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics.

Most existing sign language datasets focus on daily communication or “how-to” instructional videos. ASL STEM Wiki is different because it captures the complexity of technical discourse. The researchers curated 254 English Wikipedia articles across five domains: Science, Geography, Technology, Mathematics, and Medicine.

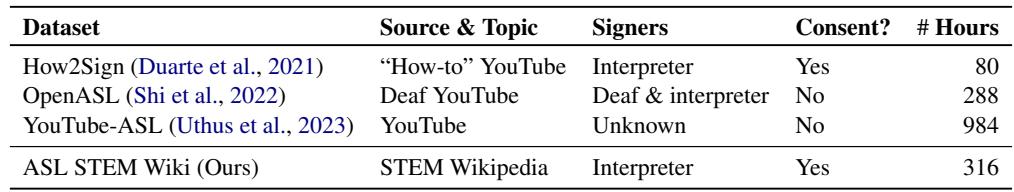

As shown in Table 1 above, ASL STEM Wiki stands out not just for its topic, but for its ethical construction. It includes over 300 hours of video from 37 certified professional interpreters, all of whom consented to the data collection. This is a crucial distinction from datasets scraped from the internet without user permission.

How the Data Was Collected

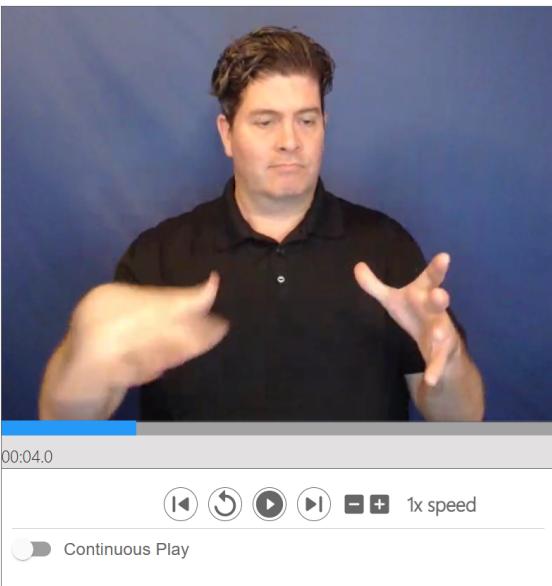

To create a parallel corpus (where English text is aligned with ASL video), the researchers built a specialized recording interface. Interpreters were presented with Wikipedia articles sentence-by-sentence.

This setup, illustrated in Figure 2, allowed for a clean mapping between the source English text and the resulting ASL video. The result is a dataset containing over 64,000 video segments. This structure allows researchers to analyze exactly how specific English scientific terms are translated—or fingerspelled—in ASL.

The Fingerspelling Phenomenon

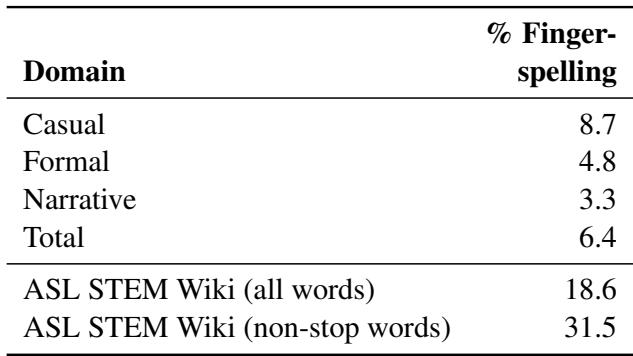

One of the most striking findings from the dataset analysis is the sheer volume of fingerspelling. In casual or narrative ASL, fingerspelling usually makes up about 3% to 8% of the content. In ASL STEM Wiki, that number jumps dramatically.

Table 2 reveals that in this STEM corpus, fingerspelling accounts for 18.6% of all words and a staggering 31.5% of non-stop words (content words). This data validates the initial hypothesis: interpreters are heavily relying on English spelling to convey technical concepts.

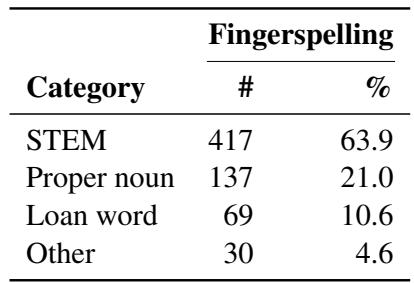

But what exactly are they spelling? The researchers analyzed the data to categorize these words.

As seen in Table 3, nearly 64% of the fingerspelled words are STEM-specific terms. This confirms that the bottleneck is indeed technical vocabulary.

The Goal: Automatic Sign Suggestion

The availability of this dataset opens the door to a new AI application: Automatic Sign Suggestion. The vision is to create a system that can assist interpreters in real-time or during preparation.

The workflow, visualized in Figure 1, operates in three steps:

- Detection: The AI analyzes the video to find segments where the interpreter is fingerspelling.

- Alignment: The AI looks at the English source sentence and figures out which word corresponds to that fingerspelling segment.

- Suggestion: Using the identified English word, the system queries a lexicon to find a proper ASL sign (if one exists) to suggest for future use.

The paper focuses on building baselines for the first two steps: Detection and Alignment.

The Model Architecture

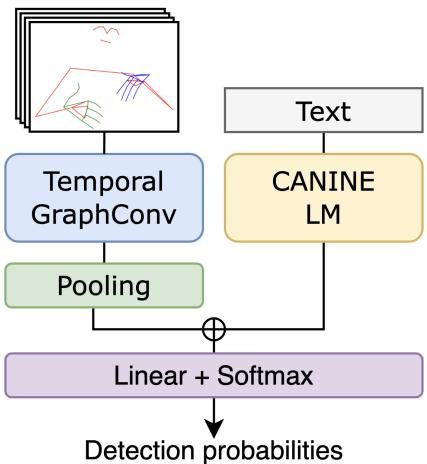

To tackle fingerspelling detection, the authors designed a neural network that processes both the visual information (the signer’s movements) and the textual information (the English sentence).

Visual Processing: Temporal Graph ConvNets

For the video input, the model doesn’t look at raw pixels. Instead, it uses MediaPipe to extract 2D “keypoints”—essentially a skeleton of the signer’s body and hands. This reduces the data complexity while keeping the most important information: the movement of the fingers and arms. These keypoints are fed into a Temporal Graph Convolutional Network, which is excellent at understanding how the relationships between body parts change over time (e.g., the rapid, intricate finger movements typical of fingerspelling).

Text Processing: CANINE

For the text input, the authors chose CANINE, a character-level language model. Standard models (like BERT) process text as whole words or sub-words. However, fingerspelling is inherently character-based (L-I-K-E T-H-I-S). By using a character-level model, the system is better aligned with the linguistic reality of the task.

The visual and textual features are concatenated (joined together) and passed through a final layer that predicts, for every frame of video, whether fingerspelling is happening.

Training Strategy: Contrastive Learning

One of the biggest challenges in machine learning is the need for labeled data. While ASL STEM Wiki is large, the researchers only had specific “fingerspelling start/end” timestamps for a small subset of the data. To get around this, they used Self-Supervised Contrastive Learning to pre-train the model.

In simple terms, contrastive learning teaches the model to recognize which pieces of data belong together and which don’t, without needing specific labels. They used two objectives:

- Temporal Contrastive: The model looks at two video clips. It has to guess if they come from the same video and, if so, which one came first. This teaches the model to understand the flow of time and movement in ASL.

- Sentential Contrastive: The model looks at a video clip and two English sentences. It has to pick which sentence matches the video. This teaches the model the relationship between the visual signs and the written text.

After this pre-training phase, the model is “fine-tuned” on the smaller set of annotated data to specifically detect fingerspelling.

Experiments and Results

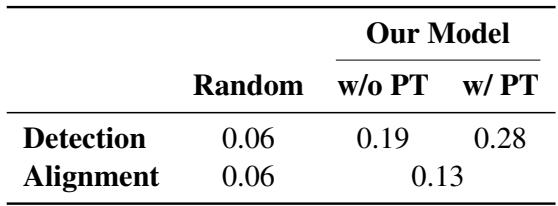

To measure success, the researchers used Intersection over Union (IOU). This metric checks how much the time segments predicted by the AI overlap with the actual time segments marked by human annotators. An IOU of 1.0 would be a perfect match; 0.0 means no overlap at all.

Table 4 presents the results. The “Random” column represents a baseline guess based on the average frequency of fingerspelling.

- Without Pre-training: The model achieves a detection IOU of 0.19.

- With Pre-training: The score jumps to 0.28.

While a score of 0.28 indicates that this is a very difficult task (leaving plenty of room for improvement), the 47% improvement gained from contrastive pre-training is a significant finding. It proves that allowing the model to “explore” the unlabeled data first helps it learn the structures of ASL much better.

For the Alignment task (matching the detected fingerspelling to a specific English word), the authors used a heuristic approach based on word frequency. The assumption is that rare words (like “photosynthesis”) are more likely to be fingerspelled than common words (like “the”). This simple method achieved an IOU of 0.13, beating the random baseline but highlighting the complexity of mapping English syntax to ASL grammar.

Challenges and Future Directions

The researchers conducted an error analysis to understand why the model struggles.

- Detection Errors: The model often confused rapid, one-handed signs with fingerspelling. It also struggled with very short fingerspelled words (like abbreviations) or when the signer transitioned seamlessly between signing and spelling.

- Alignment Errors: The heuristic assumed English and ASL word order are the same, which is often false. ASL has its own distinct grammar and syntax. Future models will need to “read” the ASL grammar rather than relying solely on the English sentence structure.

Conclusion

The ASL STEM Wiki paper represents a foundational step in accessible technology. By creating and releasing a high-quality, professional dataset, the authors have provided the raw material needed to train the next generation of AI tools.

This work highlights a critical use case for AI: not replacing human interpreters, but augmenting them. If an AI can identify fingerspelled technical terms and suggest standardized signs from a lexicon, it can help interpreters deliver smoother, more conceptually accurate translations. For a Deaf student in a university biology class, that difference could mean the distinction between struggling to decode letters and truly understanding the science of life.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2411.05783/images/cover.png)