Introduction

Imagine you are sitting at a dinner table. A friend asks, “Where is the salt?” You glance at the table and reply, “It’s just to the right of your glass.” This interaction seems effortless. It requires you to identify objects, understand the scene from your friend’s perspective, and articulate a spatial relationship.

Now, imagine asking a state-of-the-art Artificial Intelligence the same question. You might expect a model that can pass the Bar Exam or write complex code to easily handle basic directions. However, recent research suggests otherwise.

Large Multimodal Models (LMMs), such as GPT-4o, Gemini, and LLaVA, have revolutionized the intersection of computer vision and natural language processing. They can describe complex images, write poetry about sunsets, and answer detailed questions about visual content. Yet, when it comes to spatial reasoning—understanding where objects are located relative to one another—these models often exhibit surprising fragility.

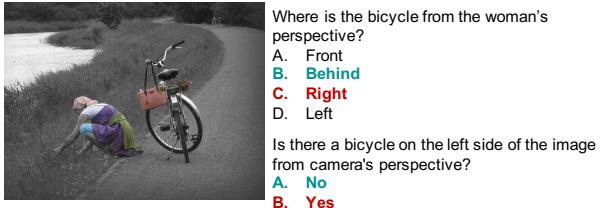

Take a look at the example below.

As shown in Figure 1, even advanced models like GPT-4o can struggle with what seems like a trivial task: identifying the location of a bicycle from a specific perspective. While the model correctly identifies the bicycle, it fails to translate that into a correct spatial relationship relative to the woman in the image.

In this post, we will explore a fascinating research paper titled “An Empirical Analysis on Spatial Reasoning Capabilities of Large Multimodal Models.” The researchers, Shiri et al., conducted a comprehensive audit of how top-tier LMMs handle spatial tasks. They constructed a new benchmark, analyzed failure points, and discovered that while these models are great at detecting objects, they are often “spatially blind” when it comes to reasoning about them.

We will break down their new dataset, Spatial-MM, examine their clever methods for improving model performance using synthetic visual cues, and analyze why “Chain of Thought” prompting—usually a magic bullet for reasoning—might not work for spatial tasks.

Background: The Spatial Gap in AI

Before diving into the methodology, we need to understand the landscape. LMMs are trained on massive datasets of image-text pairs. They learn to associate the word “cat” with visual features of a cat. However, spatial prepositions like “left of,” “under,” “facing,” or “behind” are more abstract. They depend not just on the object itself, but on its context, the viewer’s perspective, and the relationship between multiple items.

Previous benchmarks have tried to test this, but they often suffer from limitations:

- Camera Bias: Most datasets assume the “viewer” is the camera. They rarely ask questions from the perspective of a person inside the image (e.g., “From the driver’s perspective, where is the pedestrian?”).

- Lack of Complexity: Many questions are simple single-step queries. They don’t test multi-hop reasoning (e.g., “Find the cup, then find the object to its left, and tell me what color it is”).

The researchers argue that to truly understand the spatial capabilities of LMMs, we need a cleaner, more rigorous benchmark that specifically targets these weaknesses.

The Core Method: Constructing Spatial-MM

To address these gaps, the authors introduced a new benchmark called Spatial-MM. This dataset is designed to be the ultimate test for spatial awareness. It consists of two distinct subsets: Spatial-Obj and Spatial-CoT.

1. Spatial-Obj: Testing Basic Relations

This subset contains 2,000 multiple-choice questions focused on one or two objects. The goal is to assess if the model understands 36 different spatial relationships (such as beneath, attached to, facing away, top right).

The dataset isn’t just a random collection of photos. The researchers categorized the images into specific visual patterns that are known to be difficult for AI, such as:

- Object Localization: Where is X?

- Orientation and Direction: Is the giraffe facing left?

- Viewpoints: Seeing objects from top-down or different angles.

- Positional Context: Relationships between two moving objects.

Figure 2 illustrates the diversity of these patterns. Notice the “Viewpoint” example (top-right). The question asks from which viewpoint the mug is seen. This requires the model to mentally model 3D space from a 2D image—a cognitively demanding task.

2. Spatial-CoT: Testing Multi-Hop Reasoning

The second subset, Spatial-CoT, focuses on Chain of Thought (CoT). In many logic tasks, asking an AI to “think step-by-step” improves accuracy. The researchers wanted to know if this applies to spatial reasoning.

They created 310 multi-hop questions where the answer requires a sequence of reasoning steps. For example:

- Identify the woman in the floral dress.

- Identify her orientation.

- Determine what is to her right.

Crucially, the researchers didn’t just want the final answer; they wanted to verify if the reasoning path was correct. They tagged reasoning steps as either Spatial (S) (e.g., “person in front of car”) or Non-Spatial (NS) (e.g., “woman holding a fork”). This allows for a granular diagnosis of where the model fails.

Data Enrichment: Giving the Model “Hints”

One of the most interesting contributions of this paper is the hypothesis that LMMs fail because they lack explicit visual grounding. They see pixels, but they might not explicitly “box” objects or map their relationships before answering.

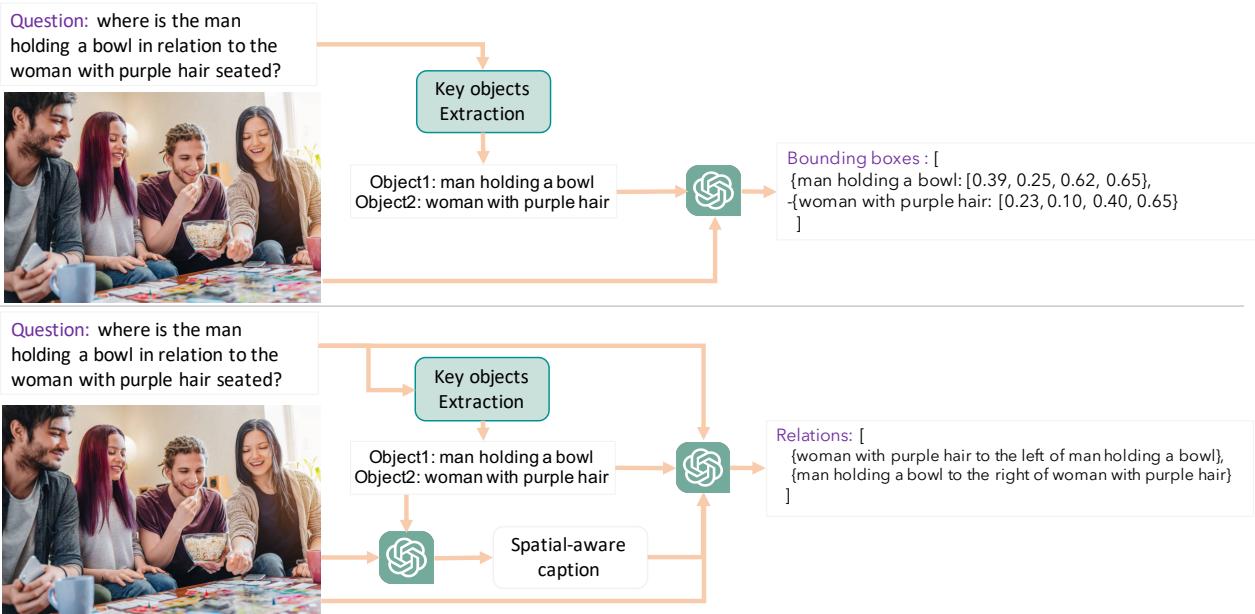

To test this, the authors developed pipelines to inject two types of “hints” into the model’s prompt: Bounding Boxes and Scene Graphs.

Pipeline 1: Bounding Box Generation

In this pipeline, the system extracts key objects from the question and asks an auxiliary model (like GPT-4o) to generate bounding box coordinates [x_min, y_min, x_max, y_max] for those objects. These coordinates are then fed back into the LMM as part of the prompt.

Pipeline 2: Scene Graph Generation

Here, the model is asked to generate a “Scene Graph”—a structured text description of relationships (e.g., man --[to the right of]--> table). This forces the model to explicitly articulate the spatial layout before attempting to answer the question.

As seen in Figure 6, the pipelines act as a pre-processing step. The top path generates precise coordinates, while the bottom path generates semantic relationships.

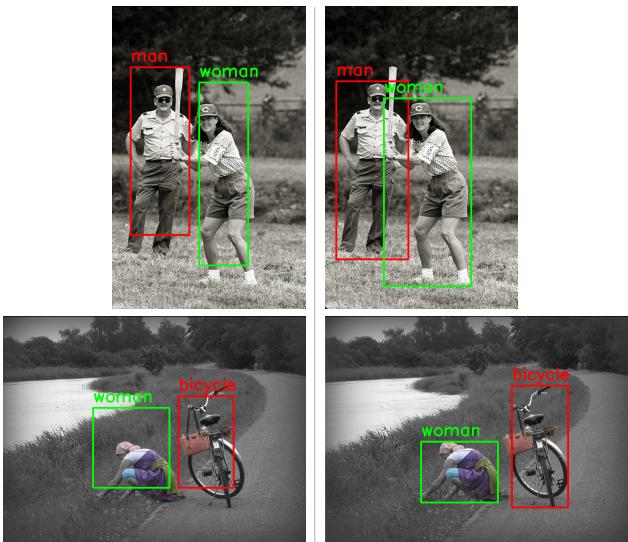

Interestingly, the researchers found that using synthetic bounding boxes (generated by GPT-4o) was often more effective than using human-annotated ground truth boxes from older datasets.

Figure 7 shows why. The ground truth boxes (left) from legacy datasets can be loose or inaccurate. The synthesized boxes (right) generated by modern LMMs are often tighter and cleaner. This suggests that while LMMs are excellent at detecting (finding the box), they struggle with reasoning (interpreting the relationship between boxes).

Experiments & Results

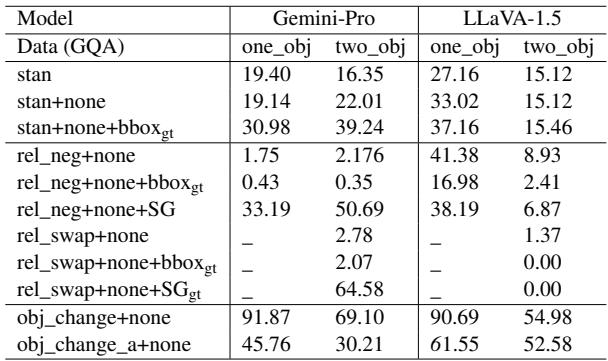

The researchers tested four major models: GPT-4o, GPT-4 Vision, Gemini 1.5 Pro, and LLaVA-1.5. They used the Spatial-MM benchmark and the GQA-spatial dataset. The results provided several critical insights.

Finding 1: Visual Hints Significantly Boost Performance

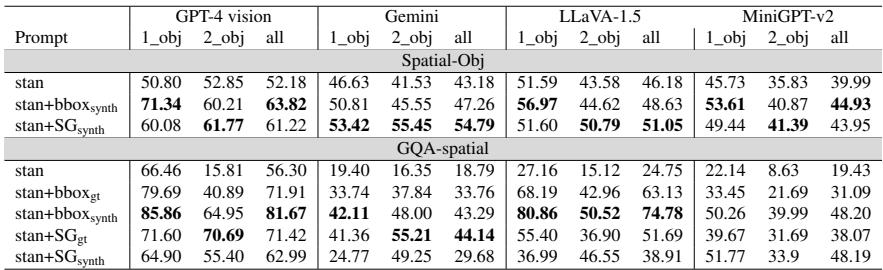

The first major finding is that LMMs are not hopeless at spatial reasoning; they just need help. When the researchers augmented the prompts with bounding boxes (bbox) or scene graphs (SG), accuracy skyrocketed.

Table 1 reveals massive improvements. For example, on the GQA-spatial dataset, providing synthesized bounding boxes (stan+bboxsynth) boosted GPT-4 Vision’s accuracy from 56.30% to 81.67%.

Key Takeaway: Bounding boxes tend to be more effective for simple, one-object questions (localization), while Scene Graphs are more effective for two-object questions (relationships).

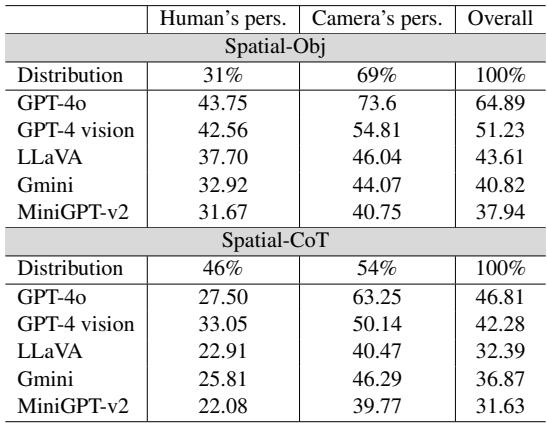

Finding 2: The “Human Perspective” Blind Spot

Most computer vision datasets are “camera-centric.” They ask questions about what is left or right in the image. But real-world utility often requires “human-centric” reasoning (e.g., a robot assistant needing to know what is to your left).

The researchers explicitly compared these two perspectives.

Table 2 shows a stark contrast. All models performed significantly worse when asked to reason from a human’s perspective inside the image. GPT-4o, the strongest model, dropped from 73.6% accuracy on camera perspective to 43.75% on human perspective. This indicates that LMMs struggle with the “Theory of Mind” required to rotate their mental viewpoint.

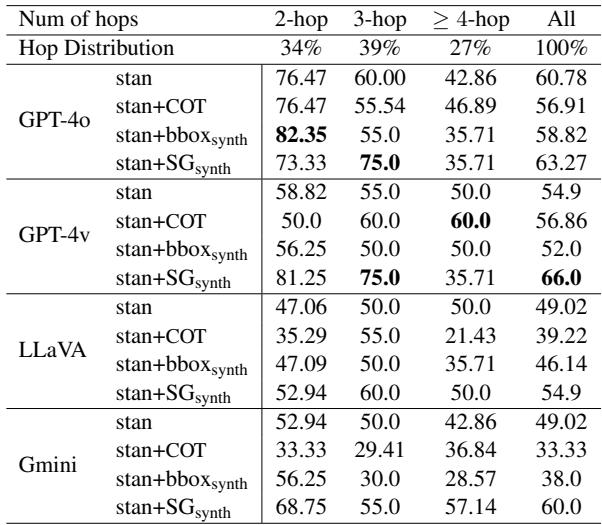

Finding 3: Chain of Thought (CoT) Fails for Spatial Tasks

In text-based logic puzzles, asking an AI to “think step-by-step” (Chain of Thought) is a standard technique to improve results. However, the authors found that for spatial multi-hop questions, CoT often hurts performance or provides no benefit.

Table 3 compares standard prompting (stan) against CoT (stan+COT). For GPT-4o, using CoT dropped accuracy from 60.78% to 56.91%.

Why? The researchers analyzed the generated reasoning paths and found that models often “hallucinate” spatial steps. They might correctly identify the objects (Non-Spatial steps) but fail to determine the correct relationship (Spatial steps) in the intermediate phase, leading the entire chain astray.

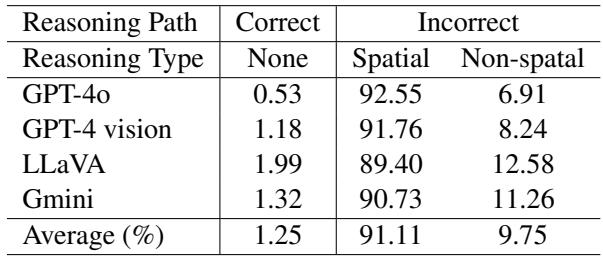

This is further detailed in the error analysis below:

Table 5 shows that when models fail, 91.11% of the time it is due to an incorrect spatial reasoning step. Non-spatial errors (like identifying a car as a truck) are rare. The models know what they are looking at, but they get lost navigating the space between objects.

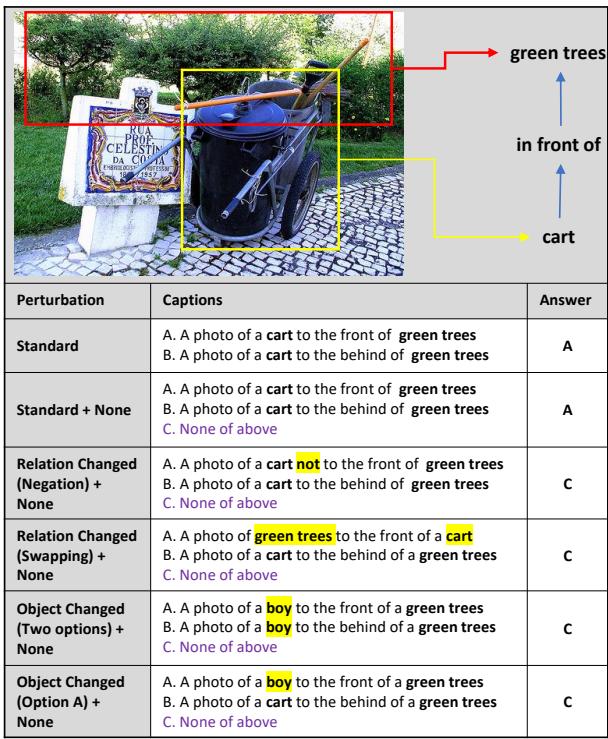

Finding 4: Fragility to Perturbation

To prove that models often guess rather than reason, the researchers applied “perturbations” to the GQA-spatial dataset. They made small changes to the text options, such as:

- Adding “None of the above.”

- Swapping “left” with “right” in the options.

- Changing object names.

If a model truly understands the image, these text changes shouldn’t confuse it. However, the results were chaotic.

Table 6 shows that simple changes, like negating the relationship (adding “not”), caused massive performance drops. For example, Gemini-Pro’s accuracy on one-object questions plummeted from 19.40% to 1.75% when negation was introduced. This suggests models are relying on shallow pattern matching between the image and text rather than a robust understanding of spatial logic.

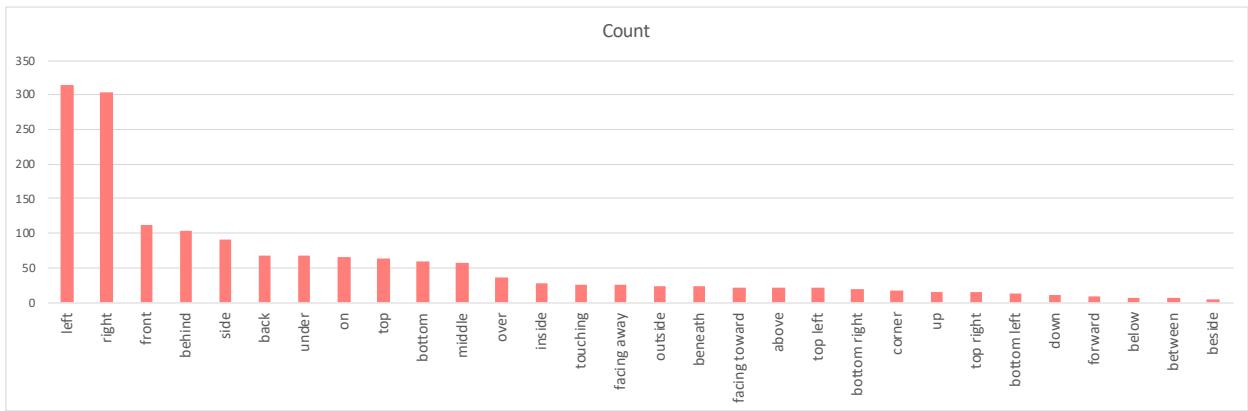

Distribution of Relations

Finally, it is worth noting the bias in the data itself. The researchers analyzed the distribution of spatial terms in their dataset.

As shown in Figure 8, the concepts of “left” and “right” dominate the dataset. More complex 3D relations like “facing away” or “beneath” are less frequent. This data imbalance partly explains why models struggle with complex 3D reasoning—they simply haven’t seen enough of it during training compared to simple 2D lateral positions.

Conclusion & Implications

The paper “An Empirical Analysis on Spatial Reasoning Capabilities of Large Multimodal Models” serves as a crucial reality check for the AI community. While LMMs dazzle us with their ability to write code or describe paintings, their grasp of physical space remains rudimentary.

Key Takeaways:

- Object Detection \(\neq\) Spatial Reasoning: LMMs are great at finding objects (detection) but poor at understanding the geometric relationships between them.

- Visual Scaffolding Works: We can significantly improve current models not by retraining them, but by enriching their prompts with Bounding Boxes and Scene Graphs. This “visual scaffolding” bridges the gap between pixel data and semantic language.

- Perspective Taking is Hard: The inability to reliably adopt a human perspective within an image limits the current utility of LMMs in robotics and navigation.

- CoT Isn’t a Silver Bullet: Standard step-by-step prompting techniques don’t automatically solve spatial puzzles; in fact, they can induce hallucinations.

What’s Next? This research points toward a need for better training data that emphasizes 3D relationships and human-centric viewpoints. It also suggests that future LMM architectures might need specialized modules for spatial processing, rather than relying entirely on the language model to “talk” its way through a visual map.

For students and researchers entering this field, Spatial-MM offers a robust new playground to test these capabilities. Solving the “left vs. right” problem might seem simple, but it is one of the final frontiers in making AI truly understand the physical world.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2411.06048/images/cover.png)