In the world of algorithmic game theory and large-scale logistics, a fundamental problem persists: how do you buy services from multiple people who might lie about their prices, while ensuring you get the best possible “bang for your buck”?

Imagine a government agency trying to procure medical supplies from various vendors, or a crowdsourcing platform hiring freelancers to label data. The buyer (auctioneer) wants to select a set of sellers to maximize the total value of the service minus the cost paid. This is known as a procurement auction.

However, there is a catch. The value of these services often exhibits diminishing returns—a property known as submodularity. For example, hiring two translators is great, but hiring a hundred might not add much more value than hiring fifty. Furthermore, the sellers are strategic; they will bid higher than their actual costs to maximize their profit.

In this deep dive, we explore a research paper that bridges the gap between complex optimization algorithms and economic mechanism design. We will look at how researchers have developed a framework to convert state-of-the-art approximation algorithms into truthful, efficient auctions.

The Core Problem: Welfare vs. Cost

The objective of this work is distinct from standard revenue maximization. The goal here is to maximize Social Welfare in a procurement setting. Specifically, the auctioneer wants to select a subset of sellers \(S\) to maximize the difference between the value obtained, \(f(S)\), and the costs incurred, \(\sum c_i\).

The challenge is that finding the optimal set \(S\) is computationally hard (NP-hard), especially when \(f(S)\) is a submodular function. To make matters worse, the auctioneer doesn’t know the true costs of the sellers—only the bids they submit.

The researchers aim to design a mechanism that satisfies three critical properties:

- Incentive Compatibility (IC): It is in the sellers’ best interest to report their costs truthfully.

- Individual Rationality (IR): Sellers never lose money by participating (their payment covers their cost).

- Non-negative Auctioneer Surplus (NAS): The value the auctioneer gets is at least as much as the total payments made.

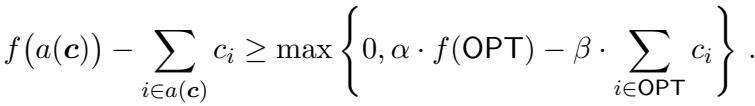

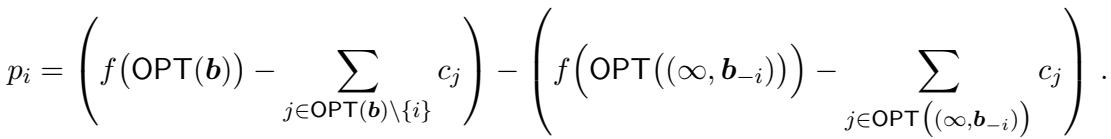

The paper provides a bi-criteria approximation guarantee for this problem, expressed as:

Here, \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) represent the trade-off in approximation. The goal is to get \(\alpha\) close to 1 and \(\beta\) close to 1.

The Algorithmic Engine: Submodular Optimization

Before we can design an auction, we need an algorithm that can solve the optimization problem assuming we did know the costs. The paper revisits several greedy algorithms and provides improved analysis for them.

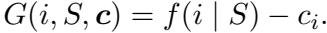

All these algorithms follow a similar “meta-algorithm” structure: they build a solution set \(S\) iteratively. In each round, they calculate a score \(G(i, S, c)\) for every item \(i\) not yet in the set. If the best score is positive, the item is added.

Let’s look at the specific scoring functions analyzed in the paper.

1. Greedy-Margin

The most intuitive approach is the Greedy-margin algorithm. It simply looks at the marginal gain—how much value an item adds minus its cost.

While simple, this algorithm doesn’t always provide the best worst-case guarantees because it doesn’t account for the “rate” of return.

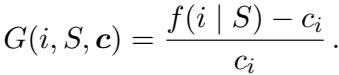

2. Greedy-Rate and ROI Greedy

To address the shortcomings of simple margins, we can look at the ratio of gain to cost (Return on Investment or ROI). The Greedy-rate algorithm prioritizes efficiency.

Alternatively, the ROI Greedy algorithm uses a slightly different denominator but achieves a similar ranking logic.

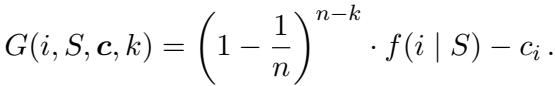

3. The Distorted Greedy Algorithm

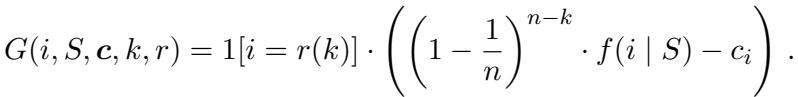

The star of the show is the Distorted Greedy algorithm. This method introduces a time-dependent distortion to the marginal contribution. As the algorithm progresses (as \(k\) increases towards \(n\)), the weight placed on the marginal value changes.

The term \((1 - 1/n)^{n-k}\) acts as a dampener. This algorithm is unique because it doesn’t necessarily stop when the marginal gain minus cost is negative; the scoring function’s structure allows it to navigate non-positive submodular maximization landscapes effectively.

The researchers also analyzed a Stochastic version of this algorithm to speed up computation, which randomly samples sellers rather than evaluating everyone at every step.

4. Cost-Scaled Greedy

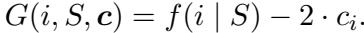

Finally, there is the Cost-scaled Greedy algorithm. This is particularly useful for online settings (where sellers arrive one by one). It effectively penalizes high costs more aggressively by multiplying the cost by a factor (in this case, 2).

Improved Theoretical Guarantees

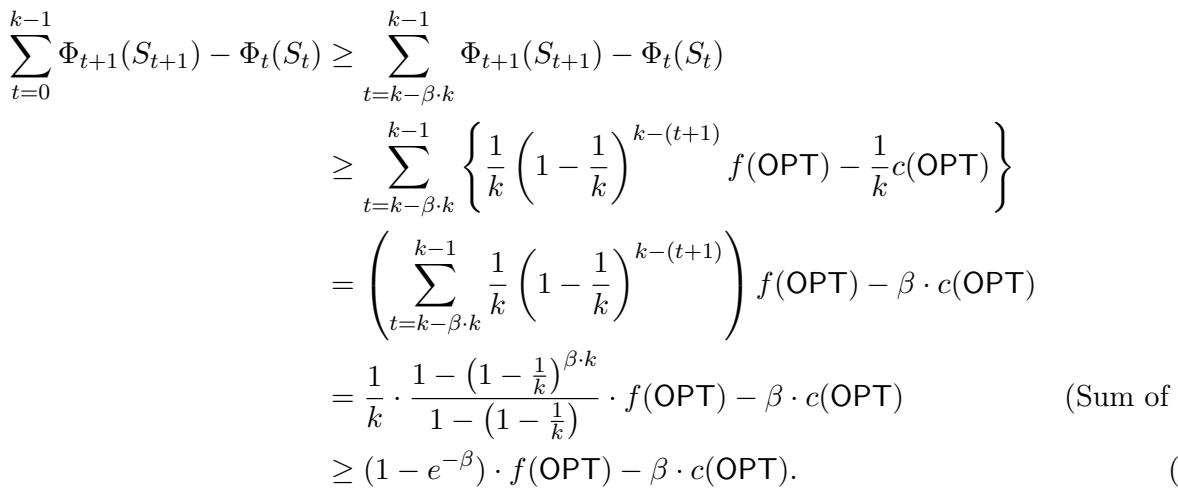

One of the paper’s theoretical contributions is a tighter analysis of the Distorted Greedy algorithm. The authors prove that this algorithm satisfies a \((1 - e^{-\beta}, \beta)\) guarantee for all \(\beta \in [0, 1]\) simultaneously. This places the algorithm on the Pareto frontier of what is theoretically possible for this class of problems.

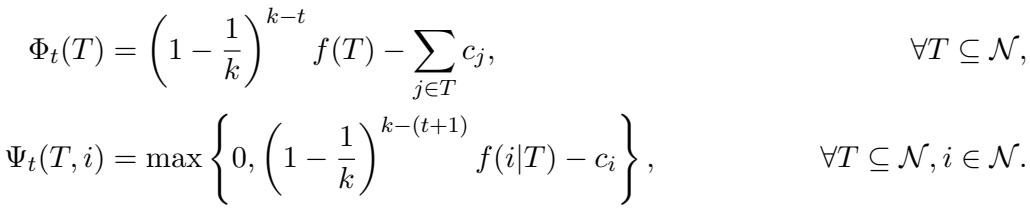

The mathematical heavy lifting involves defining potential functions \(\Phi\) and \(\Psi\) to track the progress of the algorithm’s value accumulation versus cost accumulation.

By analyzing the difference between these potential functions at each step, the authors derive the improved bounds.

This inequality shows that the algorithm accumulates value at a rate that guarantees the final welfare is close to the optimal.

From Algorithms to Mechanisms

The most significant practical contribution of this work is a framework that transforms the algorithms above into Truthful Mechanisms.

In mechanism design, the VCG (Vickrey-Clarke-Groves) mechanism is the standard solution for ensuring truthfulness. It calculates payments based on the “externality” a player imposes on others.

However, VCG has a fatal flaw in this context: it requires solving the optimization problem exactly to maintain truthfulness. Since our problem is NP-hard, we can’t run VCG efficiently.

The New Framework

The authors propose a method to convert the greedy algorithms described above into mechanisms that are computationally efficient and truthful.

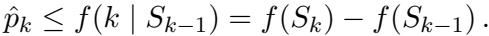

The intuition relies on the Critical Payment concept. For a mechanism to be truthful, the allocation rule (who wins) must be monotone (bidding lower never hurts your chances), and the payment must be the “threshold” bid. If a seller had bid any higher than this threshold, they would have lost; any lower, and they still win.

The framework works as follows:

- Allocation: Run the chosen meta-algorithm (e.g., Distorted Greedy) using the submitted bids as costs.

- Payment: For each winning seller \(i\), rerun the algorithm assuming seller \(i\) bid \(\infty\) (essentially removing them). Then, find the highest possible bid \(b_i\) seller \(i\) could have submitted and still been selected by the algorithm.

The paper proves that as long as the scoring function \(G\) is non-increasing in the bid \(b_i\) (which all the greedy algorithms are), this construction yields an IC and IR mechanism.

Ensuring Non-negative Auctioneer Surplus (NAS)

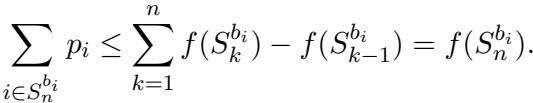

Crucially, the mechanism must ensure the auctioneer doesn’t go broke. The total payments to sellers must not exceed the value \(f(S)\) generated.

The proof for this relies on the property that a seller is only picked if their score is positive. This implies a bound on their bid relative to their marginal contribution.

By summing these bounds over all winners, the authors show that the total payment is bounded by the telescoping sum of marginal contributions, which equals the total value.

This confirms that the auctioneer is safe: the surplus will always be non-negative.

Online and Descending Auctions

The framework extends beyond static, sealed-bid auctions.

Online Mechanisms

In many gig-economy applications, workers (sellers) arrive sequentially. The auctioneer must decide instantly whether to hire them. This is modeled as an Online Mechanism.

The authors show that the algorithms can be converted into Posted-Price Mechanisms. When a seller arrives, the algorithm calculates a “take-it-or-leave-it” price based on the history of previous sellers.

If the seller’s cost is below this threshold, they accept the job. This preserves the approximation guarantees of the underlying online algorithm (like Cost-scaled Greedy).

Descending Auctions

A Descending Auction (or Dutch Auction) works by starting with a high price and lowering it until sellers agree to accept it. These are popular because they are “obviously strategy-proof”—the best strategy is clearly to stay in the auction until the price hits your cost.

The paper uncovers a surprising result regarding descending auctions in adversarial settings (where the order of price reduction is worst-case). They show that a descending auction using a “perfect” demand oracle (one that solves the optimization exactly) can actually perform arbitrarily poorly.

However, if the auctioneer uses a demand oracle based on the Cost-scaled Greedy algorithm, the auction retains a \((1/2, 1)\) approximation guarantee. This is a fascinating instance where an approximate algorithm is more robust than an exact one in a dynamic auction setting.

Experimental Results

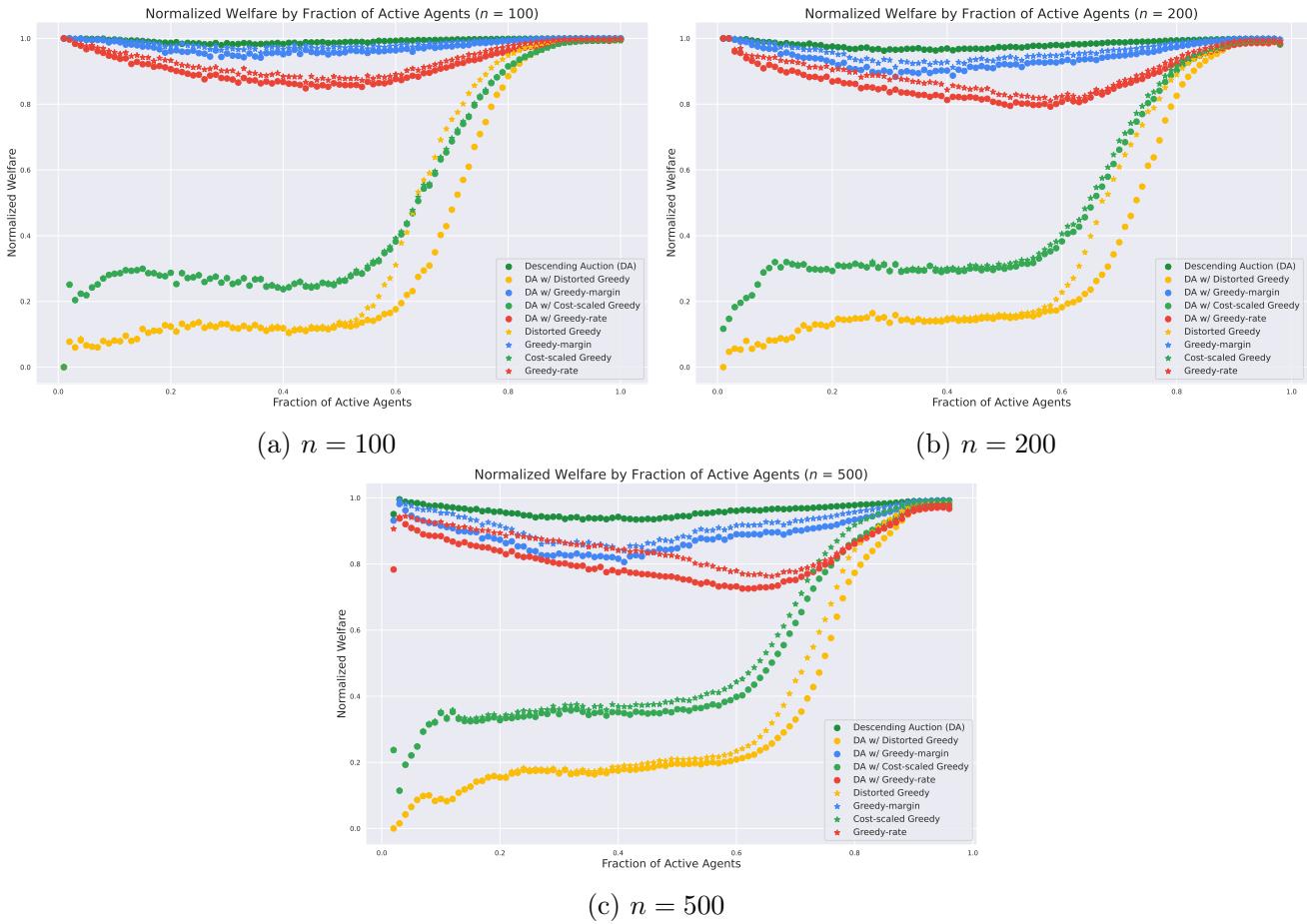

To validate these theoretical frameworks, the researchers ran experiments using the SNAP “Wiki-Vote” dataset, simulating a coverage problem (a classic submodular function). They compared the runtime and welfare of the different mechanisms.

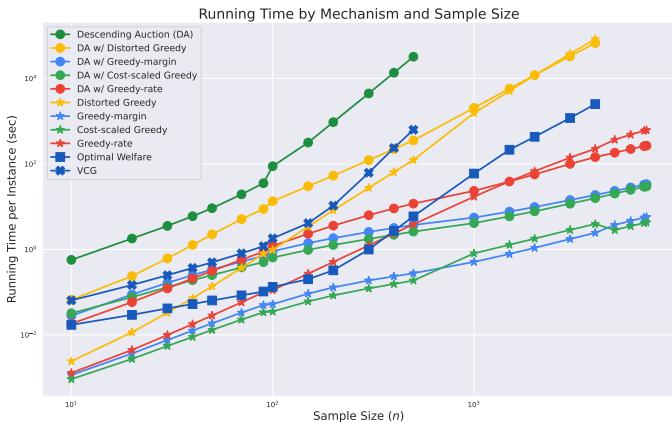

Runtime

As expected, calculating the exact optimal welfare (and VCG payments) is exponentially slow. The greedy-based mechanisms are orders of magnitude faster.

In Figure 1, notice how the VCG and “Descending Auction” (with exact oracle) lines shoot up, while the greedy variants (Greedy-margin, Cost-scaled) remain low. The Distorted Greedy is slightly slower than other greedy methods but still polynomial.

Welfare Performance

How much value is lost by using these approximations? The experiments plotted welfare against the “Fraction of Active Agents” (a proxy for how competitive the market is).

In Figure 2, we see the normalized welfare. The key takeaway is the hierarchy of performance:

- Greedy-margin generally performs the best among approximations.

- Greedy-rate and Cost-scaled follow.

- Distorted Greedy, while theoretically robust, sometimes lags slightly in average-case empirical welfare compared to the aggressive Greedy-margin.

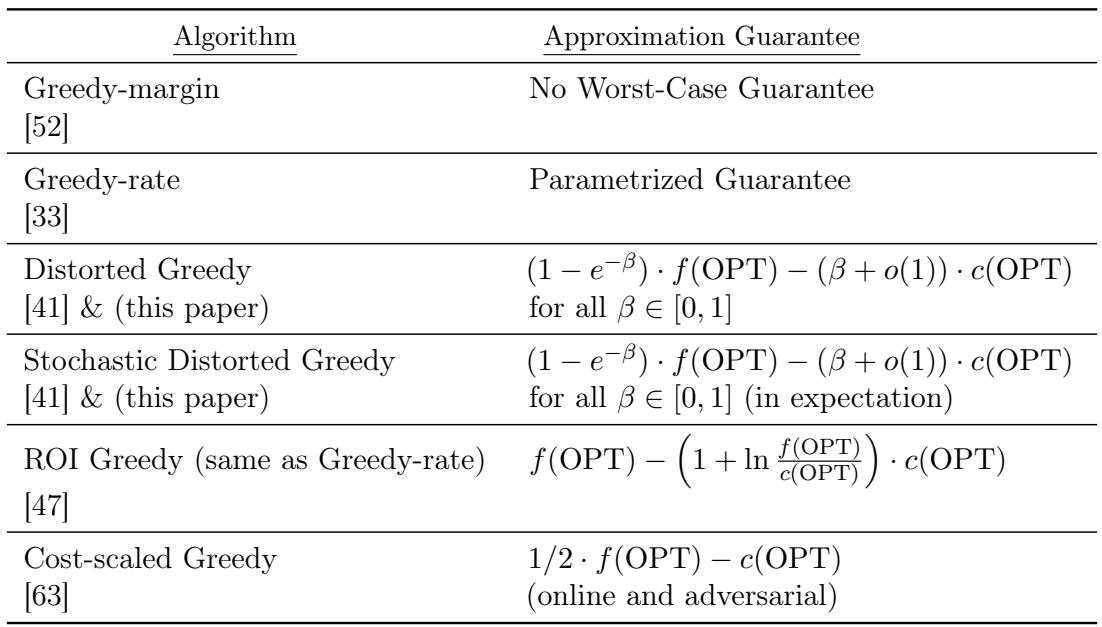

Table 1 summarizes the theoretical guarantees of the algorithms instantiated in this framework.

It is interesting to note that while Greedy-margin performs well in practice (Figure 2), it has no worst-case theoretical guarantee (Table 1). Conversely, Distorted Greedy has the best theoretical guarantee but is more conservative in practice.

Conclusion

This research provides a comprehensive toolkit for modern procurement. By leveraging the specific mathematical properties of submodular functions, the authors have created a bridge between two worlds:

- Optimization: Efficiently solving complex selection problems.

- Economics: Handling strategic behavior and ensuring truthful bidding.

The proposed framework allows practitioners to take “off-the-shelf” submodular optimization algorithms and wrap them in a payment scheme that guarantees truthfulness and budget safety. Whether for offline sealed-bid auctions or real-time online markets, this work offers a rigorous path toward more efficient and fair procurement systems.

For students and engineers building the next generation of logistics or crowdsourcing platforms, the lesson is clear: you don’t have to choose between computational speed and economic robustness. With the right mechanism design, you can have both.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2411.13513/images/cover.png)