Imagine you are trying to teach a robot how to “make a cup of coffee” by only letting it watch hours of video footage of people moving around a kitchen. The footage has no captions, no rewards, and no explanations. The robot sees a human pick up a mug, but it doesn’t know why. Was the goal to clean the mug? To move it? Or was it the first step in making coffee?

This scenario highlights a massive bottleneck in Artificial Intelligence today. We want agents that can follow natural language instructions in complex environments (like “book a restaurant” or “navigate to the blue room”). However, current methods usually require one of two expensive things: massive amounts of manually labeled data (where every action is annotated), or the ability to practice in the real world millions of times (which is slow and dangerous).

In a recent paper titled “TEDUO: Teaching the Environment Dynamics from Unlabeled Observations,” researchers Thomas Pouplin, Katarzyna Kobalczyk, Hao Sun, and Mihaela van der Schaar propose a groundbreaking solution. They introduce a pipeline that allows AI agents to learn robust, language-conditioned policies from unlabeled, offline data by leveraging the synergy between Reinforcement Learning (RL) and Large Language Models (LLMs).

In this deep dive, we will unpack how TEDUO works, why it matters, and how it manages to teach LLMs “common sense” about physical environments without expensive supervision.

The Core Problem: The Grounding Gap

To understand why TEDUO is necessary, we first need to look at the limitations of our current best tools: Reinforcement Learning (RL) and LLMs.

Reinforcement Learning is excellent at mastering specific tasks (like Chess or Dota 2) by maximizing a reward signal. However, RL agents struggle to generalize. If you train an RL agent to “open the red door,” it often fails completely if you ask it to “open the blue door” unless it has been explicitly trained on that specific goal.

Large Language Models (LLMs), like GPT-4 or Llama, are the opposite. They have incredible general knowledge. They know that “opening a door” requires being near the door. However, they lack grounding. An LLM might know the concept of a key, but it doesn’t intuitively understand the specific physics of a GridWorld environment—that you can’t walk through walls, or that you must face an object to pick it up.

The challenge is to combine the grounding of RL with the generalization of LLMs, all while using cheap, unlabeled data.

TEDUO: A Three-Step Solution

TEDUO stands for Teaching the Environment Dynamics from Unlabeled Observations. The method is designed to take a “dumb” dataset of random interactions and turn it into a smart, general-purpose agent.

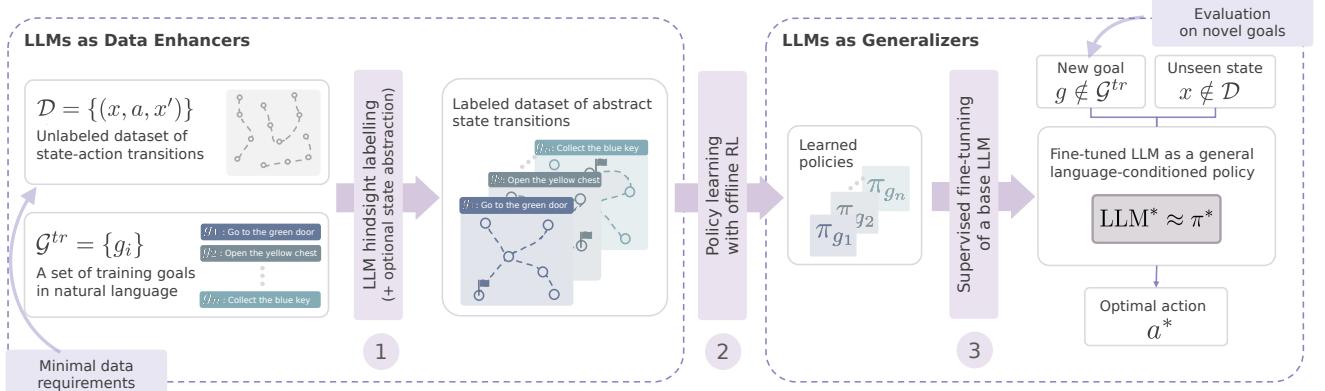

The researchers propose a sequential pipeline that uses LLMs in two distinct roles: first as a tool to clean and label data, and second as the brain of the final agent.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the pipeline consists of three distinct phases:

- Construction of Solvable MDPs: Using LLMs to label the raw data and simplify the world.

- Offline Policy Learning: Using classic RL to learn specific skills from the labeled data.

- LLM Supervised Fine-Tuning: Teaching a base LLM to mimic the RL expert, effectively transferring the “muscle memory” of RL into the “reasoning brain” of the LLM.

Let’s break these steps down in detail.

Step 1: Making Sense of the Noise (Data Enhancement)

The input to TEDUO is a dataset \(\mathcal{D}\) of observations: triplets of (state, action, next state). Crucially, these are unlabeled. We don’t know what goal the agent in the data was trying to achieve, or if they were acting randomly.

To learn from this, we need to know two things:

- What happened? (Hindsight Labeling)

- What is important? (State Abstraction)

Hindsight Labeling with Proxy Rewards

Standard RL needs a reward function to learn. Since the data has no rewards, TEDUO synthesizes them. The system takes a list of possible goals (e.g., “pick up the red ball”) and checks if any state in the dataset satisfies that goal.

Using a massive LLM to check every state in a dataset of millions of frames would be prohibitively expensive and slow. The authors solve this by training a lightweight Proxy Reward Model. They use a powerful LLM to label a small subset of data, and then train a small, fast neural network to predict those labels for the rest of the dataset. This allows them to “hindsight label” the entire dataset efficiently.

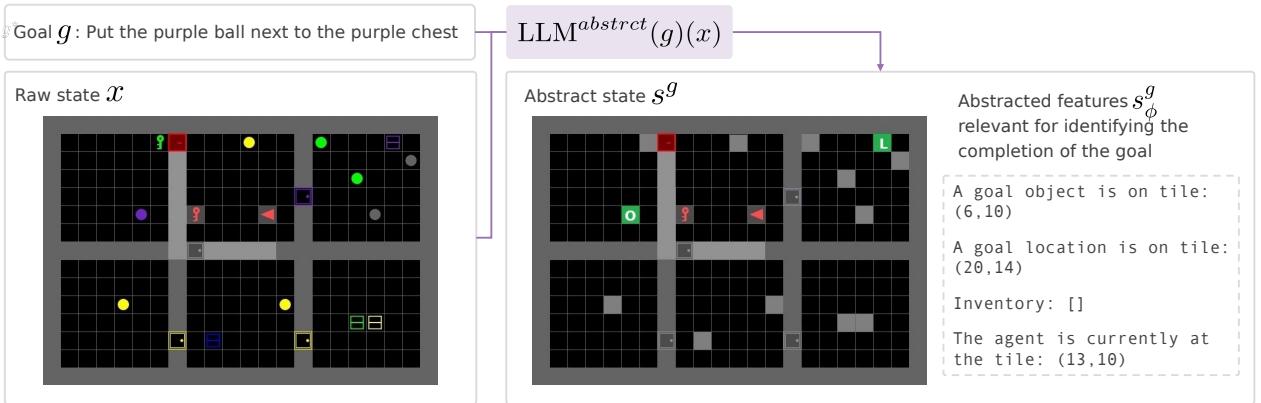

State Abstraction

Raw environments are noisy. In a visual grid world, the color of the floor or the position of a distant, irrelevant object might confuse the agent. This is known as the “Curse of Dimensionality.”

TEDUO employs an optional but highly effective LLM-based State Abstraction. The researchers ask an LLM: “Given the goal is ‘pick up the blue key’, what features in this list are relevant?”

As shown in Figure 2, the LLM acts as a filter. If the goal is to interact with a purple ball, the LLM advises the system to ignore the color of opened doors or irrelevant distinct objects, treating them effectively as walls or generic obstacles.

This transforms a high-dimensional, noisy state \(x\) into a clean, abstract state \(s^g\). This reduction makes the subsequent Reinforcement Learning step much faster and more data-efficient because the RL algorithm doesn’t waste time analyzing irrelevant pixels.

Step 2: Developing “Expert” Instincts (Offline RL)

At this point, we have a labeled dataset where irrelevant information has been filtered out. Now, for every training goal (e.g., “Go to the red room”), we treat the data as a specific Markov Decision Process (MDP).

The researchers use Offline Reinforcement Learning—specifically tabular Q-learning or Deep Q-learning—to solve these MDPs.

The objective here is not to create the final agent, but to create a “teacher.” The algorithm crunches the data to find the optimal policy \(\pi^g\) for specific goals present in the training set.

It is important to note that these policies are brittle. A Q-learning agent trained strictly to “pick up the red ball” cannot generalize to “pick up the blue key” if it hasn’t seen that specific reward signal. However, these agents are grounded—they perfectly understand the physics of the environment for the tasks they know.

Step 3: The Knowledge Transfer (LLM Fine-Tuning)

This is the most innovative part of TEDUO. We now have a set of “expert” policies for specific goals, but we want an agent that can handle any goal.

The researchers create a new supervised dataset, \(\mathcal{D}^{SFT}\). They take the expert policies from Step 2 and generate “perfect” trajectories. They effectively ask the RL experts: “If you were at state \(S\), what is the absolute best action to take to achieve goal \(G\)?”

This results in a dataset of (Goal, State, Optimal Action Sequence).

\[ \begin{array} { r l } & { \mathcal { D } ^ { S F T } : = \{ ( g , s _ { 0 } ^ { g } , [ a _ { 0 } ^ { * , g } , \ldots , a _ { n _ { g } } ^ { * , g } ] ) : g \in \mathcal { G } ^ { t r } , \ s _ { 0 } ^ { g } \in \mathcal { D } ^ { g } , } \\ & { \qquad a _ { t } ^ { * , g } = \underset { a \in \mathcal { A } } { \arg \operatorname* { m a x } } \pi ^ { g } ( a \mid s _ { t } ^ { g } ) , } \\ & { \qquad s _ { t + 1 } ^ { g } = \underset { s \in \mathcal { S } ^ { g } } { \arg \operatorname* { m a x } } \hat { P } ^ { g } ( s | s _ { t } ^ { g } , a _ { t } ^ { * , g } ) \} , } \\ & { \qquad n _ { g } s . t . R _ { \hat { \theta } } ( s _ { n _ { g } + 1 } ^ { g } ; g ) = 1 \} , } \end{array} \]They then use this dataset to Supervised Fine-Tune (SFT) a pre-trained LLM (like Llama-3).

Why does this work?

- Prior Knowledge: The LLM already understands natural language synonyms, compositionality (understanding that “red ball” and “blue key” are similar concepts), and high-level planning.

- Grounding: By training on the RL trajectories, the LLM learns the specific mechanics of the environment (e.g., “I cannot move forward if a wall is in front of me”).

The result is a single model that possesses the linguistic flexibility of an LLM and the physical grounding of an RL agent.

Experimental Results: Does It Work?

The authors evaluated TEDUO on BabyAI, a complex grid world environment, and WebShop, an e-commerce simulation. They asked several critical questions.

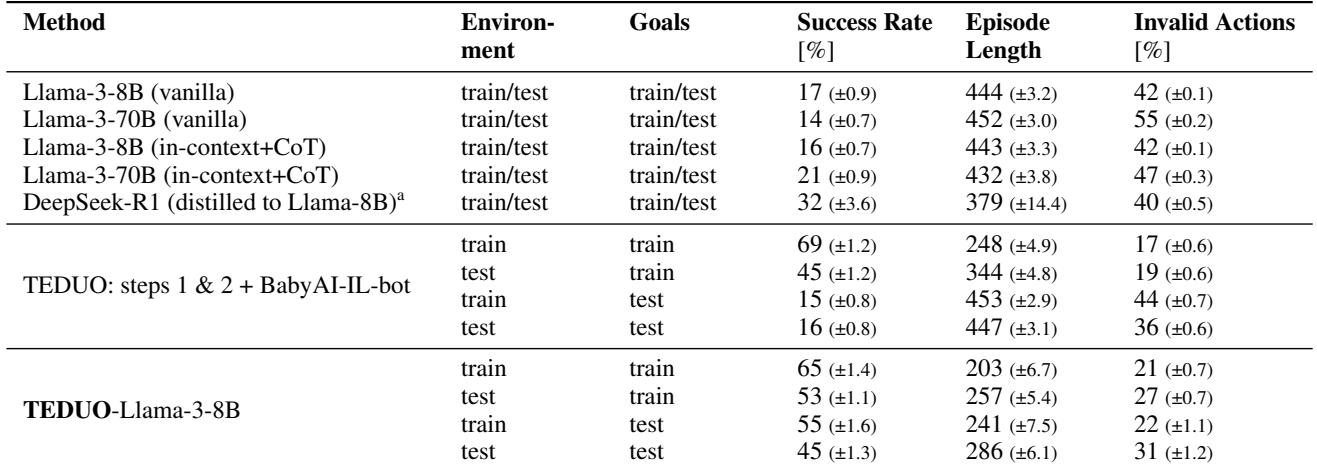

Q1: Can it Generalize to New Goals?

This is the holy grail. The researchers trained the model on a set of 500 goals and then tested it on 100 entirely new goals involving different objects and colors.

Table 1 reveals striking results:

- Vanilla LLMs (Llama-3-8B/70B) fail miserably (14-17% success rate). They simply don’t understand the environment’s rules.

- TEDUO achieves a 45% success rate on unseen test goals.

- BabyAI-IL-bot (Baseline): A standard imitation learning baseline trained on the same data performs decently on training goals (69%) but crashes to 16% on test goals. It memorized the training data but failed to learn the underlying logic.

This proves that TEDUO doesn’t just memorize solutions; it learns how to solve problems, allowing it to adapt to new instructions.

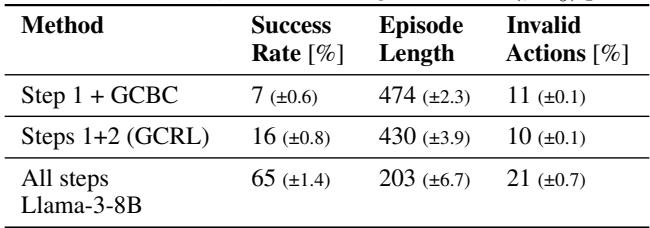

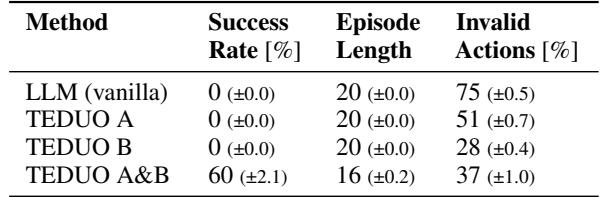

Q2: Is the Whole Pipeline Necessary? (Ablation Study)

You might wonder, “Do we really need the RL step? Can’t we just clone the data directly?”

Table 2 shows the breakdown.

- Step 1 + GCBC: If you just use the data labels and try to clone behavior (Goal-Conditioned Behavioral Cloning), success is very low (7%). This is likely because the original data was “noisy” or suboptimal.

- Steps 1+2 (GCRL): If you stop after the RL step, you get decent performance on training goals, but zero ability to handle new language commands, because Q-learning tables can’t process new sentences.

- All Steps (TEDUO): The full pipeline yields the highest success rate (65%), confirming that the LLM fine-tuning is crucial for synthesizing the skills.

Q3: Is it Memorization or Skill Learning?

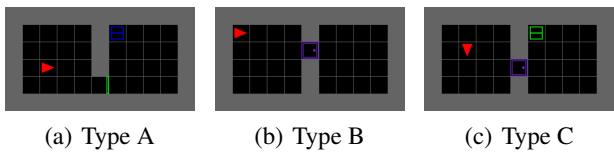

To test if the agent is actually learning compositional skills, the researchers set up a clever experiment with three environment types.

- Type A: Tasks involving picking up items (no doors).

- Type B: Tasks involving opening doors (no items).

- Type C: Tasks requiring both opening a door and picking up an item.

They trained agents on Type A and Type B, but never Type C. Then, they tested on Type C.

As shown in Table 3, an agent trained only on A fails at C. An agent trained only on B fails at C. But TEDUO A&B (trained on both separate tasks) successfully recombines those skills to solve Type C (60% success).

This demonstrates Compositionality. The LLM learned the concept of “opening” and “picking up” separately and combined them zero-shot to solve a complex, multi-step task.

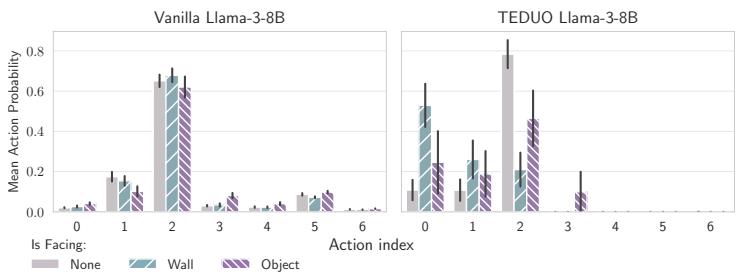

Q4: What is Going On Inside the LLM?

One of the most fascinating parts of the paper is the interpretability analysis. The researchers probed the internal layers of the LLM to see what it “knew” about the environment.

In Figure 4(a), we see the probability of taking the “Move Forward” action (Action 2). The Vanilla LLM (Left) confidently tries to move forward even when facing a wall (Teal bar). It’s essentially hallucinating that it can walk through obstacles.

The TEDUO-tuned LLM (Right), however, shows a massive drop in “Move Forward” probability when facing a wall. It has learned the physical constraint.

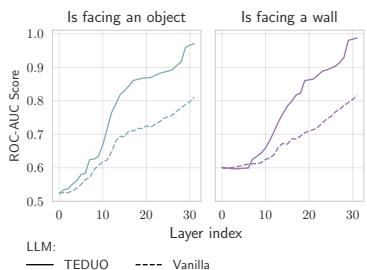

Furthermore, Figure 4(b) (below) shows the results of a “Linear Probe”—a simple classifier trying to detect if there is a wall based on the LLM’s internal neuron activations.

The TEDUO model (Solid line) achieves near-perfect detection of walls and objects in its deeper layers. This proves the fine-tuning didn’t just teach it to parrot text; it fundamentally altered how the model represents the physical state of the world.

Data Efficiency

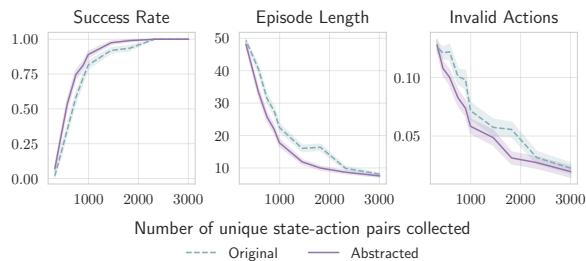

Finally, the authors showed that their method is highly efficient. Because of the abstraction step (removing irrelevant details), the RL algorithms converge much faster.

Figure 5 shows that using the abstraction function (Solid Purple Line) allows the agent to reach high success rates with far fewer data samples compared to using raw states (Dashed Blue Line). This is critical for real-world applications where data collection is expensive.

Conclusion: The Future of Offline Agents

TEDUO represents a significant step forward in making AI agents more autonomous and easier to train. By treating Large Language Models not just as chatbots, but as flexible “generalizers” that can be grounded by traditional Reinforcement Learning, the researchers have unlocked a way to train agents using only passive, unlabeled data.

Key Takeaways:

- Dual Role of LLMs: TEDUO uses LLMs to clean data (annotation) and to act (policy), playing to the model’s strengths in both areas.

- Generalization: Unlike standard RL, TEDUO agents can understand and execute commands they never saw during training.

- Low-Fidelity Data: The method works with unlabeled, potentially noisy observational data, removing the need for expensive human annotation.

This research paves the way for “watch and learn” AI—agents that can observe human behavior (like video logs of computer usage or smart home sensors) and learn not just to mimic the actions, but to understand the underlying mechanics well enough to perform entirely new tasks. As compute power scales, methods like TEDUO could become the standard for training the next generation of embodied AI assistants.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2412.06877/images/cover.png)