Predicting the future is difficult. Predicting exactly when a critical event—like the failure of a machine part or, more importantly, the survival time of a patient in a clinical trial—will occur is even harder. In high-stakes fields like healthcare, a simple “best guess” isn’t enough. Doctors and patients need to know the uncertainty of that guess. They need a guarantee: “We are 90% sure the patient will survive at least \(X\) months.”

In the world of machine learning (ML), Conformal Prediction has emerged as the gold standard for providing these rigorous statistical guarantees. However, applying it to survival analysis has historically been plagued by a tricky data problem known as censoring.

In this post, we will dive deep into a research paper by Matteo Sesia and Vladimir Svetnik, titled “Doubly Robust Conformalized Survival Analysis with Right-Censored Data.” We will explore how they solved the “missing data” problem in survival analysis using a clever imputation strategy, creating a method that remains reliable even when our models are imperfect.

The Problem: Survival Analysis and The Missing Clock

To understand the contribution of this paper, we first need to understand the unique data landscape of survival analysis.

In a standard regression problem (like predicting house prices), for every house in your training set, you know the final sale price. In survival analysis, our target variable \(T\) is the time until an event (e.g., death or relapse). However, we often don’t get to observe \(T\) for everyone.

Some patients drop out of the study. Others are still alive when the study ends. For these individuals, we don’t know their true survival time \(T\); we only know that they survived at least until a certain time \(C\) (the censoring time).

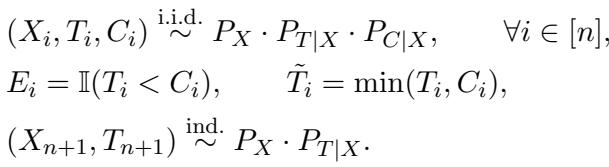

This creates a dataset where for each individual \(i\), we observe a feature vector \(X_i\) (age, blood pressure, etc.) and an observed time \(\tilde{T}_i\), which is the minimum of the true event time and the censoring time. We also get an indicator \(E_i\) telling us which one we saw.

As shown in the equation above, if the event happens (\(E_i=1\)), we see the true time \(T\). If the patient is censored (\(E_i=0\)), we only see \(C\).

The Censoring Headache

Recent advancements in conformal prediction (by researchers like Candès, Lei, and Gui) have successfully created Lower Prediction Bounds (LPBs) for survival times. An LPB is a value \(\hat{L}(X)\) such that we can guarantee with probability \(1-\alpha\) (e.g., 90%) that the true survival time \(T\) is greater than \(\hat{L}(X)\).

However, previous methods largely relied on a simpler scenario called Type-I Censoring. In Type-I censoring, the “end time” of the study is fixed and known for everyone. If a patient dies, we know exactly when they died, and we know when they would have been censored had they lived (usually the study end date).

Real-world data, however, usually presents Right-Censoring. Here, if a patient experiences the event (\(T < C\)), we see the event time, but we do not know when they would have been censored. Maybe they would have dropped out the next day; maybe they would have stayed for years. That value \(C\) is latent (hidden).

This missing information breaks standard conformal prediction algorithms. How can you calibrate your uncertainty if you don’t know the full story of the data distribution?

The Solution: DR-COSARC

Sesia and Svetnik introduce DR-COSARC (Doubly Robust Conformalized Survival Analysis with Right-Censored Data). The core philosophy of this method is a two-step “Impute and Calibrate” approach.

If the problem is that we don’t know the censoring time \(C\) for people who died, why don’t we use machine learning to make an educated guess?

Step 1: The Imputation Trick

The researchers assume “conditional independent censoring,” meaning that survival time \(T\) and censoring time \(C\) are independent given the patient’s features \(X\). This allows them to train a Censoring Model (\(\hat{\mathcal{M}}^{\mathrm{cens}}\)) alongside the standard Survival Model.

The Censoring Model learns the probability distribution of a patient dropping out or the study ending.

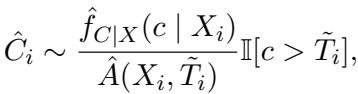

The algorithm iterates through the calibration data (the data used to tune the uncertainty bounds). For patients who were censored (\(E_i=0\)), we already know \(C_i\), so we keep it. For patients who experienced the event (\(E_i=1\)), the algorithm imputes a synthetic censoring time \(\hat{C}_i\).

Crucially, we can’t just pick any number. We know that for these patients, the censoring time must be greater than the time they died (\(C > T\)). The method samples a new censoring time from the estimated conditional distribution, restricted to values larger than the observed death time \(\tilde{T}_i\).

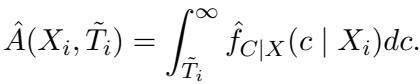

In the equation above, \(\hat{f}_{C|X}\) is the estimated probability density of the censoring time. To make this a valid probability, they normalize it by the probability of the censoring time being greater than the observed event time \(\tilde{T}_i\):

By performing this imputation, the researchers transform a messy Right-Censored dataset into a synthetic Type-I Censored dataset. Once the data is in this format, existing conformal prediction machinery can be applied.

Step 2: Conformal Calibration

With the “completed” dataset in hand, DR-COSARC applies weighted conformal inference. It uses the survival model to generate a raw score (like a predicted median survival time) and then calculates a cutoff adjustment that ensures 90% coverage on the calibration data.

The paper integrates two main approaches for this calibration:

- Fixed Cutoffs: Predicting if a patient survives past a single, fixed time point.

- Adaptive Cutoffs: Predicting survival times tailored to each specific patient’s risk profile. The authors generally recommend this adaptive approach as it provides more informative (tighter) bounds.

The “Double Robustness” Safety Net

The “DR” in DR-COSARC stands for Doubly Robust. This is a powerful theoretical property. In statistical estimation, double robustness usually means you have two models (here, the Survival Model and the Censoring Model), and your final result is valid if either one of them is correct.

- Scenario A: Your Survival Model is perfect, but your Censoring Model (and thus your imputation) is bad. The method still works because the survival model already knows the truth about \(T\).

- Scenario B: Your Survival Model is terrible (it’s a hard problem!), but your Censoring Model is good. The method still works because the conformal calibration uses the accurate weights from the censoring model to fix the survival model’s errors.

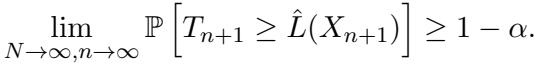

This is formalized mathematically by proving that the coverage probability converges to the target \(1-\alpha\):

The validity holds asymptotically as the sample sizes grow, providing a strong safety net for researchers using this tool in uncertain environments.

Experimental Results

The authors tested DR-COSARC against several benchmarks, including an “Oracle” (perfect knowledge), an “Uncalibrated” model, and a “Naive” application of conformal prediction (Naive CQR) that ignores the right-censoring complexity.

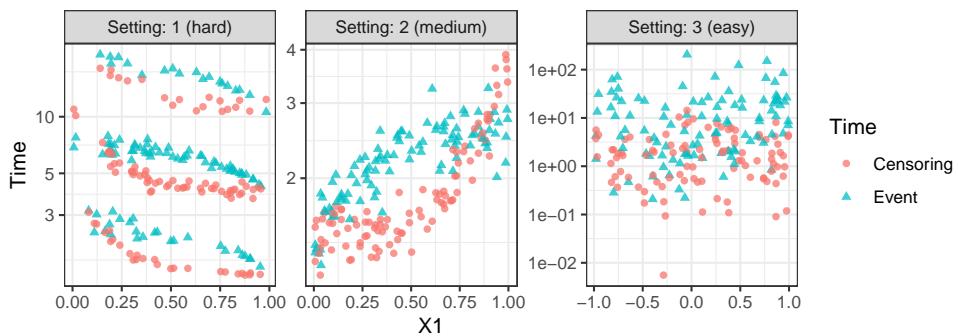

They generated synthetic data with varying degrees of difficulty.

As seen in Figure A1 above, the data simulates complex relationships between covariates (\(X\)) and times. “Setting 1” is particularly nasty, designed to make fitting an accurate survival model very difficult.

Performance on Synthetic Data

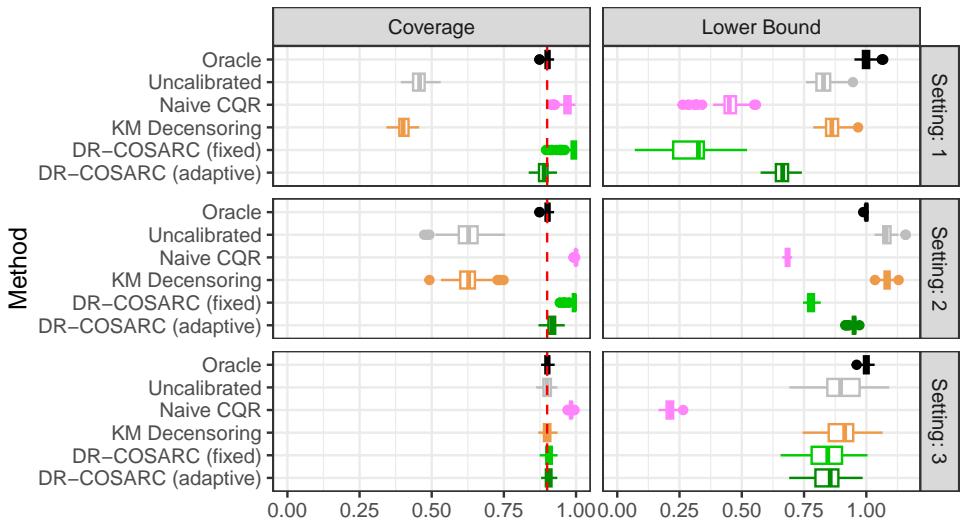

The results in Figure 1 (below) are striking, particularly in the difficult “Setting 1” (top row).

- Coverage (Left Column): Look at the top-left graph. The “Uncalibrated” method (gray) fails miserably, covering far fewer than the required 90% of cases. The “Naive CQR” (pink) technically covers enough but does so by being uselessly conservative (giving tiny bounds). DR-COSARC (green squares and stars), however, sticks close to the dashed red line (the target 90% coverage), even in this hard setting.

- Lower Bound (Right Column): We want these values to be high (informative). Predicting “you will survive at least 0 days” is valid but useless. DR-COSARC provides bounds that are competitive with the Oracle, maximizing informativeness while maintaining safety.

Proving Double Robustness

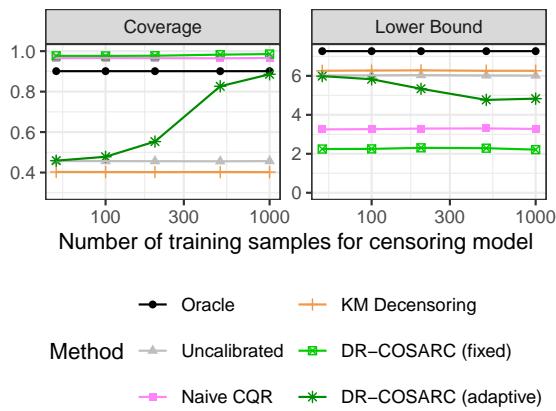

To empirically prove the “Double Robustness” claim, the authors ran an experiment where they deliberately varied the quality of the Censoring Model by changing the number of training samples available to it, while keeping the survival model fixed.

In Figure 2 (above), specifically in the difficult Setting 1 (where the survival model is known to struggle), we see the power of the censoring model. As the number of training samples for the censoring model increases (x-axis), the coverage of DR-COSARC (green lines) climbs up to the target 90%.

This confirms the theory: when the survival model is weak, a good censoring model rescues the method.

Real-World Application

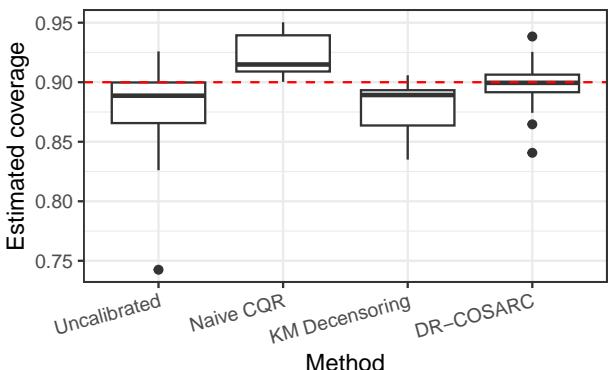

Finally, the researchers applied DR-COSARC to seven real-world medical datasets, including studies on lung cancer (VALCT), breast cancer (METABRIC), and heart transplants (HEART).

In Figure 3, we see the distribution of estimated coverage across these datasets. The “Uncalibrated” methods often dip below the 0.90 target (the red dashed line), creating a risk for patients. DR-COSARC (the right-most boxplot) consistently centers its mass right on or above the target, providing reliable, safe predictions across different medical contexts.

Why This Matters

Survival analysis is moving away from simple Cox Proportional Hazards models toward complex Machine Learning models like Random Survival Forests and Deep Neural Networks. These models are powerful, but often “black boxes” that can be overconfident.

DR-COSARC bridges the gap. It allows researchers to use powerful ML models to predict survival while maintaining the statistical rigor required for clinical decision-making. By solving the right-censoring “blind spot” via imputation, it ensures that we don’t throw away valuable data from patients who experienced events, nor do we make invalid assumptions about those who were censored.

The “Double Robustness” property is the cherry on top—it acknowledges that in the real world, models are rarely perfect. By requiring only one of the two components to be accurate, DR-COSARC offers a resilient, practical tool for modern survival analysis.

This post summarizes the paper “Doubly Robust Conformalized Survival Analysis with Right-Censored Data” by Matteo Sesia and Vladimir Svetnik.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2412.09729/images/cover.png)