Introduction

In the computational chemistry revolution, Machine Learning (ML) has become the new lightsaber. It cuts through the heavy computational cost of density functional theory (DFT) and quantum mechanics, allowing researchers to simulate larger systems for longer times than ever before. The premise is simple: train a neural network to predict how atoms interact, and you can model everything from drug discovery to battery materials at lightning speeds.

However, as we push for faster and more scalable models, a fundamental debate has emerged regarding the “laws of physics” we impose on these networks. Traditionally, interatomic forces are calculated as the derivative of potential energy—a method that guarantees energy conservation. But a new wave of “non-conservative” models suggests we can skip the energy calculation and predict forces directly, trading physical rigor for computational speed.

In the research paper “The dark side of the forces,” Filippo Bigi, Marcel F. Langer, and Michele Ceriotti investigate whether this tradeoff is worth it. They uncover significant dangers in ignoring energy conservation, demonstrating that “direct force” models can lead to catastrophic simulation failures. But they also offer a way out: a hybrid approach that harnesses the speed of the dark side without succumbing to its instability.

The Physics: Potentials vs. Direct Forces

To understand the controversy, we need to revisit a bit of classical mechanics. In atomistic simulations, the behavior of atoms is governed by a Potential Energy Surface (PES), denoted as \(V\).

The force \(\mathbf{f}\) acting on an atom is defined as the negative gradient (the slope) of this potential energy with respect to the atom’s position \(\mathbf{r}\):

Because the force is derived from a scalar energy field, it is conservative. This means that if you move atoms around in a closed loop and return them to their starting positions, the total mechanical work done is zero. Energy is neither created nor destroyed; it is conserved.

The Computational Bottleneck

In the context of Neural Networks, enforcing this relationship comes with a cost. To get the force, you first predict the energy \(V\), and then use automatic differentiation (backpropagation) to calculate the derivative \(\partial V / \partial \mathbf{r}\).

While effective, this backpropagation step is computationally expensive—typically increasing the cost of inference by a factor of 2 to 3 compared to a simple forward pass.

To bypass this bottleneck, recent architectures (like ORB, Equiformer, and others) have proposed predicting the force vector \(\mathbf{f}\) directly in the forward pass, ignoring the underlying energy \(V\) entirely. This is faster and simpler to implement. However, by breaking the link between force and energy, these models are no longer guaranteed to conserve energy. They become non-conservative.

Diagnosing the “Dark Side”

How do we measure if a model is breaking the laws of physics? The researchers propose checking the Jacobian matrix \(\mathbf{J}\) of the forces. If forces are derivatives of an energy, the matrix of second derivatives (the Hessian) must be symmetric (\(J_{ij} = J_{ji}\)).

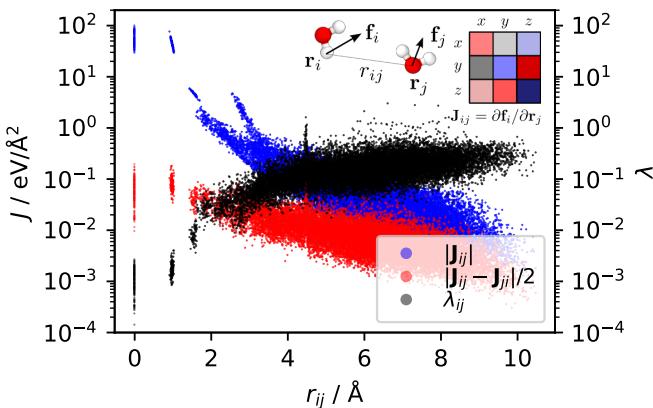

If a model predicts forces directly, this symmetry is not enforced. The researchers defined a metric, \(\lambda\), to quantify how “non-conservative” a model is by measuring the asymmetry of its Jacobian.

As shown in Figure 1, the asymmetry (measured by \(\lambda\)) doesn’t just disappear at long distances. In fact, for interactions between distant atoms (blue dots), the non-conservative component (asymmetry) is often as large as the interaction itself. This suggests that non-conservative artifacts are pervasive throughout the spatial interactions of the molecule.

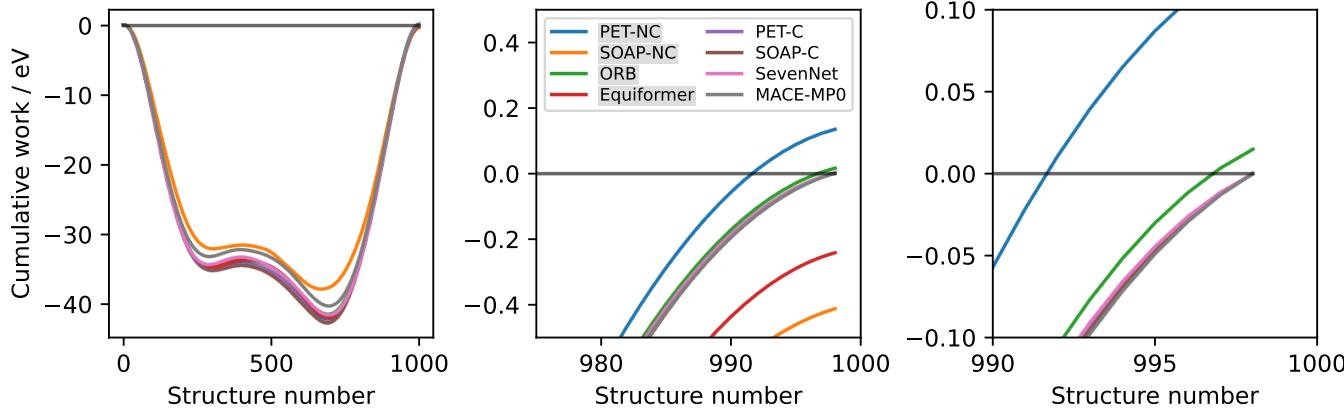

To visualize this practically, the authors calculated the work done by different models when moving atoms along a closed path.

In Figure 6, you can see the difference clearly. Conservative models (like PET-C and SOAP-BPNN-C) integrate to exactly zero work when the loop closes. Non-conservative models (like ORB and PET-NC), however, result in a non-zero value. They have effectively manufactured (or destroyed) energy out of thin air simply by moving the atoms in a circle.

The Consequences: Exploding Simulations

One might argue that small errors in energy conservation are acceptable if the model is fast. However, the paper demonstrates that these “small” errors accumulate rapidly in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations.

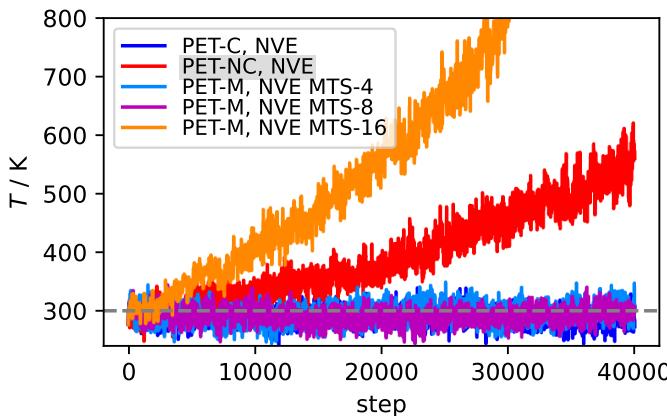

The Infinite Heating Problem (NVE Ensemble)

In an NVE simulation (constant Number of atoms, Volume, and Energy), an isolated system should maintain a stable temperature.

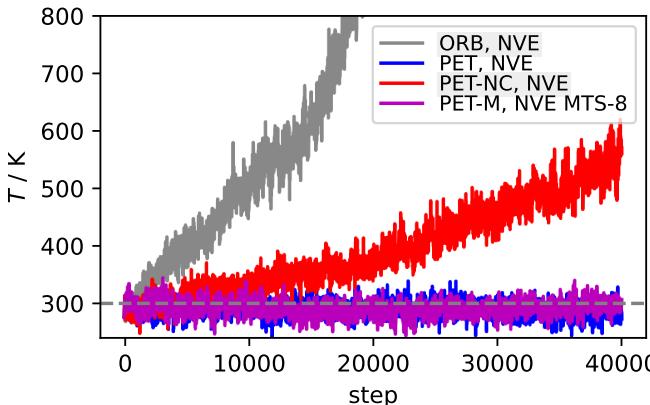

Figure 2 reveals the catastrophic failure of non-conservative models in this setting.

- Blue Line (PET): The conservative model maintains a stable temperature (after initial equilibration).

- Gray & Red Lines (ORB, PET-NC): The non-conservative models exhibit a runaway heating effect.

Because the non-conservative forces constantly pump spurious work into the system, the atoms move faster and faster. The paper notes that for the PET-NC model, this drift corresponds to a heating rate of 7,000 billion degrees per second. This makes direct-force models essentially useless for standard energy-conserving simulations.

The Thermostat Trap (NVT Ensemble)

A common counter-argument is that most simulations use a thermostat (NVT ensemble) to keep the temperature constant, which should siphon off the excess heat.

The researchers tested this by applying aggressive Langevin thermostats. While strong thermostats could keep the temperature stable, they introduced a new problem: they destroyed the dynamics of the system.

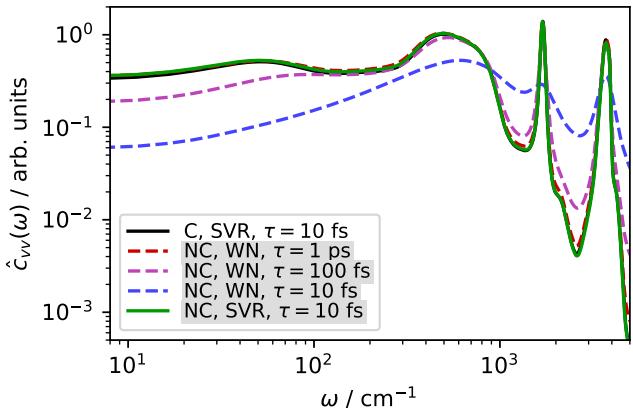

Figure 3 shows the velocity power spectrum (which relates to how atoms vibrate and diffuse).

- Black Line: The conservative reference.

- Green/Blue/Purple: Non-conservative models with various thermostats.

To keep the non-conservative models from exploding, the thermostat had to be so aggressive (\(\tau=10\) fs) that it dampened the natural motion of the water molecules (the green line), significantly altering the diffusion coefficient. You are effectively freezing the physics to fix the math.

The Solution: Best of Both Worlds

The authors conclude that while pure non-conservative models are dangerous for simulation, the computational speed of direct force prediction is too valuable to discard completely. They propose two hybrid strategies to utilize “dirty” direct forces safely.

1. Fast Pre-training, Conservative Fine-tuning

You can use the speed of direct force prediction during the heavy lifting of training. The strategy is:

- Train a model to predict forces directly (fast training, no backprop overhead).

- Take that pre-trained model and add an “energy head.”

- Fine-tune the model for a few epochs using the rigorous, conservative backpropagation method.

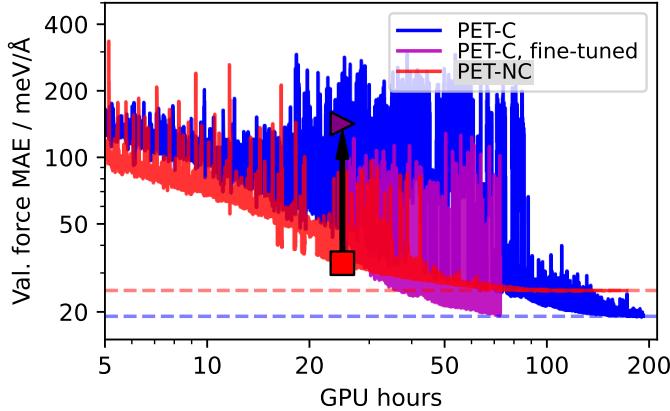

Figure 14 illustrates the power of this approach. The magenta line (Fine-tuned) achieves the same low error as the fully conservative model (Blue line) but does so in a fraction of the GPU hours. This allows researchers to train massive “Foundation Models” efficiently without sacrificing physical validity.

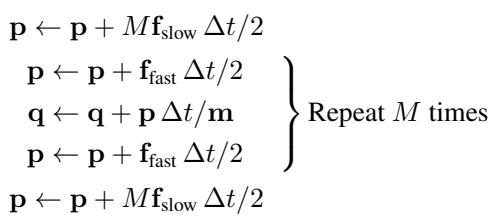

2. Multiple Time Stepping (MTS)

For running simulations, the authors suggest using Multiple Time Stepping. In this scheme, you use the cheap, non-conservative forces for the majority of the integration steps (the “fast” inner loop) and correct them periodically with the expensive, conservative forces (the “slow” outer loop).

By evaluating the expensive conservative forces only once every 8 steps (\(M=8\)), the simulation remains stable and physically accurate, while running almost as fast as the non-conservative model.

Figure 16 proves the effectiveness of MTS. While the pure non-conservative model (Red) heats up uncontrollably, the MTS simulation with \(M=8\) (Purple) remains perfectly stable, indistinguishable from the fully conservative baseline (Blue), but significantly faster.

Conclusion

The allure of the “dark side”—predicting forces directly to save computational cost—is strong in machine learning. However, this research highlights that abandoning energy conservation is not a harmless approximation; it fundamentally breaks the mechanics of molecular simulation, leading to unphysical heating and distorted dynamics.

The good news is that we don’t have to choose between speed and physics. By treating direct force predictions as a tool for acceleration—via pre-training or multiple time stepping—rather than a replacement for potential energy, we can build the next generation of atomistic models that are both lightning-fast and physically sound.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2412.11569/images/cover.png)