Introduction

Imagine asking an AI to tell you a bedtime story—not by reading text you provide, but by hallucinating a brand-new narrative, in a human voice, complete with pauses, sighs, and intonation. Now, imagine asking it to keep going for twenty minutes.

For years, this has been the “final boss” of Generative Spoken Language Modeling. While models like AudioLM or GSLM can generate impressive snippets of speech lasting 10 or 20 seconds, they inevitably fall apart over longer durations. They begin to ramble incoherently, get stuck in repetitive loops, or simply dissolve into static. The computational cost of remembering the beginning of a conversation while generating the middle becomes astronomically high.

This brings us to a groundbreaking paper: SpeechSSM.

The researchers behind SpeechSSM have tackled the problem of “unbounded” speech generation. By moving away from the standard Transformer architecture and adopting State-Space Models (SSMs), they have created a system capable of generating coherent, long-form speech (tested up to 16 minutes and theoretically infinite) without running out of memory or losing the plot.

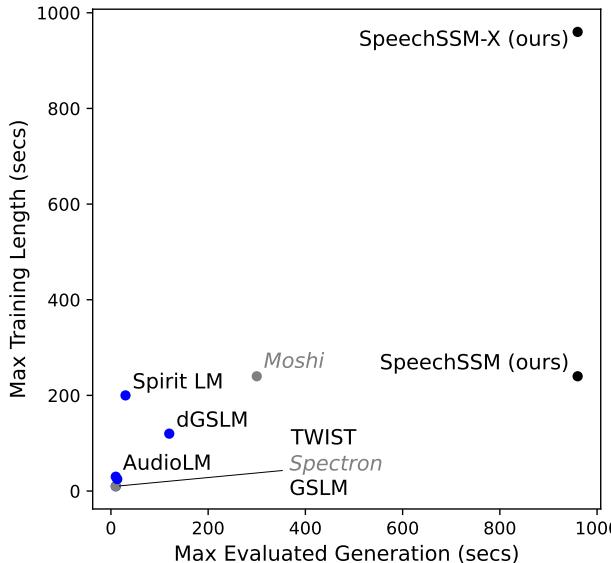

As shown in Figure 1, existing models (like AudioLM or GSLM) are clustered in the bottom-left corner—trained on short clips and capable of generating only slightly longer clips. SpeechSSM (top right) breaks this paradigm, training on multi-minute sequences and generating effectively indefinitely.

In this deep dive, we will explore how SpeechSSM achieves this, why “textless” modeling is so hard, and how the authors built a new benchmark to prove their success.

The Background: Why is Long-Form Speech Hard?

To understand the breakthrough, we first need to understand the bottleneck. Most modern language models, whether for text (like GPT-4) or speech, rely on the Transformer architecture.

Transformers utilize an “attention” mechanism. To decide what word (or sound) to generate next, the model looks back at every single token it has generated so far. This works beautifully for paragraphs. However, audio is dense. A single second of audio might be represented by 50 to 100 discrete tokens. A 10-minute speech clip could contain tens of thousands of tokens.

For a Transformer, the cost of “looking back” grows quadratically (\(O(N^2)\)) with the sequence length. As the speech gets longer, the model becomes slower and consumes massive amounts of memory. Eventually, it hits a hardware limit. Furthermore, Transformers often struggle to “extrapolate”—if you train them on 30-second clips, they simply don’t know how to structure a 5-minute narrative.

Enter the State-Space Model (SSM)

This is where State-Space Models come in. Unlike Transformers, which keep a history of everything, SSMs maintain a compressed “state”—a fixed-size memory vector that evolves over time. When predicting the next token, the model looks at its current state and the current input.

The computational complexity is linear (\(O(N)\)) rather than quadratic. This means generating the 10,000th second of audio takes the exact same amount of memory and compute as generating the 1st second. This property is crucial for the “unbounded” generation the authors aimed to achieve.

The Core Method: Inside SpeechSSM

SpeechSSM is not just a model swap; it is a carefully designed pipeline that separates what is being said (semantics) from who is saying it (acoustics).

1. The Architecture: Hybrid SSM (Griffin)

The heart of the system is the semantic language model. The researchers chose a hybrid architecture called Griffin.

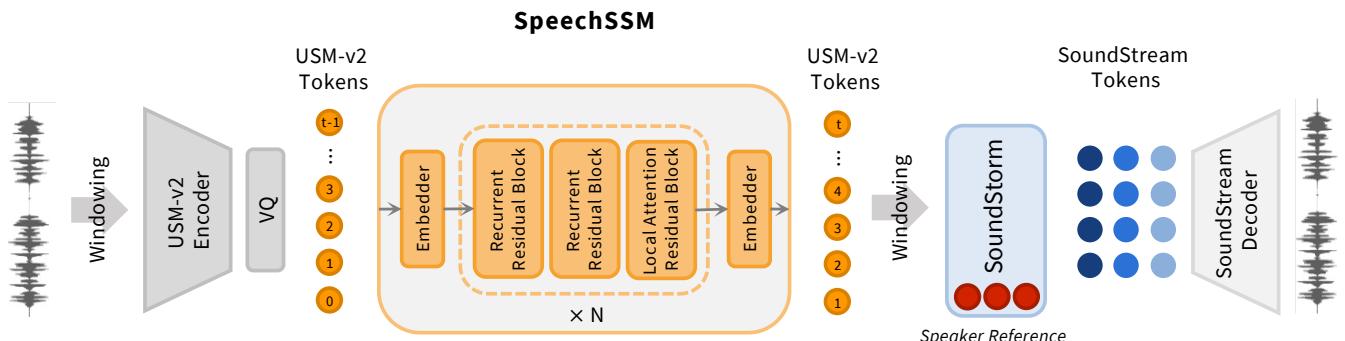

As illustrated in Figure 3 (Left), the model doesn’t process raw audio waves directly. Instead, it operates on Semantic Tokens.

- Input: The model uses USM-v2 tokens. These are discrete codes derived from a Universal Speech Model. Crucially, these tokens are highly speaker-invariant. They capture the meaning and linguistic content of the speech but strip away the specific voice characteristics.

- The Griffin Block: This block mixes Gated Linear Recurrences (the SSM part) with Local Attention. The recurrence handles long-term dependencies (remembering the topic of the story), while the local attention focuses on the immediate context (pronouncing the current word correctly).

Because the model uses recurrent layers, it has a constant memory footprint during decoding. You can run it for hours without your GPU running out of VRAM.

2. Tokenization and Windowing

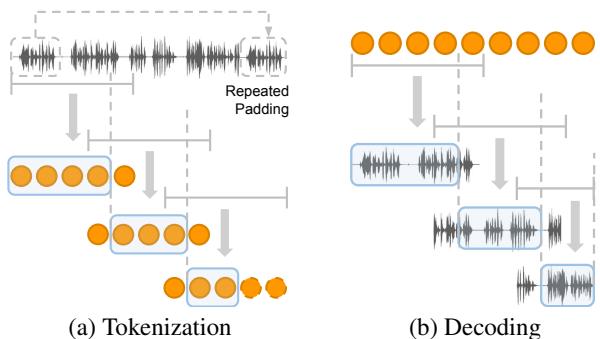

To handle effectively infinite streams of audio, you can’t just feed a 1-hour file into a tokenizer all at once. The authors implemented a Windowed Tokenization and Decoding strategy.

Looking at Figure 4, we see how this works:

- Input (Figure 4a): Long audio is chopped into fixed-size windows with overlaps.

- Synthesis (Figure 4b): When generating audio, the model produces tokens in chunks. To avoid “clicks” or discontinuities at the boundaries, the windows overlap. The final stream is stitched together by taking the first half of one window and blending it into the second half of the next.

This approach solves the “implicit End-of-Sequence (EOS)” problem. If a model is trained on fixed-length clips, it often learns that “when I get to token 1000, I should stop talking.” By using sliding windows and padding, SpeechSSM is tricked into always thinking it’s in the middle of a stream, preventing it from prematurely going silent.

3. Acoustic Synthesis: Putting the Voice Back In

Since the semantic model (Griffin) operates on “voice-less” semantic tokens, we need a way to turn that back into rich, human-sounding audio.

This is handled by the Acoustic Generator shown in the right half of Figure 3. The authors use SoundStorm, a non-autoregressive model.

- Prompting: SoundStorm is conditioned on a short 3-second audio prompt of a specific speaker.

- Generation: It takes the semantic tokens from the Griffin model and the speaker prompt, and generates SoundStream acoustic tokens (codec codes).

- Result: These acoustic tokens are decoded into a waveform.

This separation of concerns is brilliant. The heavy lifting of “staying on topic for 10 minutes” is handled by the efficient SSM on semantic tokens. The heavy lifting of “sounding like a specific person” is handled by the non-autoregressive synthesizer, which doesn’t need long-term memory—it just needs to maintain the timbre of the voice.

The Evaluation Challenge

How do you measure if a 5-minute generated story is “good”?

In the past, researchers used ASR Perplexity (transcribing the audio and checking if the text is predictable) or Auto-BLEU. The authors argue these are insufficient for long-form speech. ASR fails when the audio contains mumbled gibberish, and perplexity scores don’t capture if a story wanders off-topic after minute 3.

To fix this, the paper introduces a new benchmark and new metrics.

LibriSpeech-Long

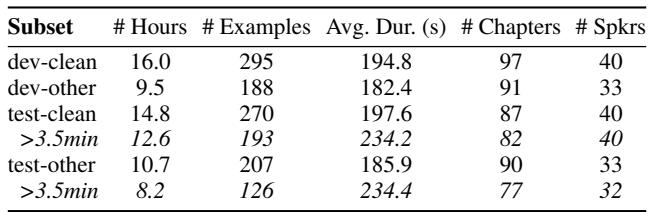

Standard datasets (like LibriSpeech) are chopped into short 10-second utterances for speech recognition training. This is useless for testing long-form coherence. The authors went back to the original audiobooks and re-processed them to create LibriSpeech-Long.

As shown in Table 1, this new dataset contains chapters chopped into segments up to 4 minutes long. This provides a ground truth for testing whether a model can maintain a narrative for hundreds of seconds.

New Metrics

- LLM-as-a-Judge: Instead of relying on rigid formulas, the researchers transcribe the generated audio and the ground truth audio. They then feed both transcripts to a large language model (like Gemini) and ask: “Which of these continuations is more coherent and fluent?”

- Time-Stratified Evaluation: They measure quality over time. They check the metrics for the first minute, the second minute, and so on, to detect when the model starts to degrade.

Experiments & Results

The researchers compared SpeechSSM against strong baselines like GSLM, TWIST, and Spirit LM. They also created a “SpeechTransformer” baseline—a model identical to SpeechSSM but using a Transformer architecture—to isolate the benefits of the State-Space approach.

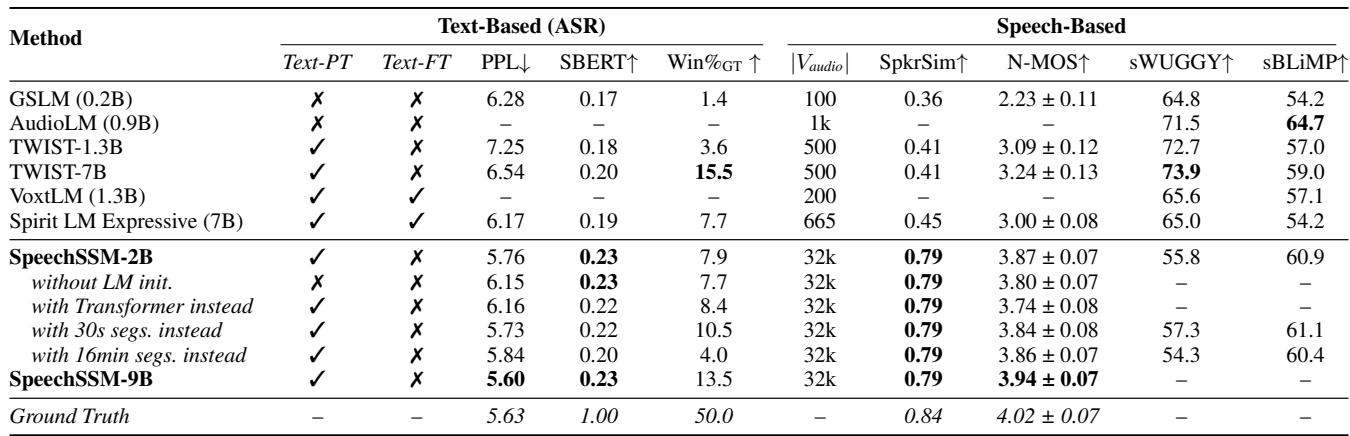

Short-Form Performance (The Sanity Check)

First, they checked if SpeechSSM is competitive on the standard short tasks (7-second generations).

Table 2 reveals that SpeechSSM (bolded) holds its own.

- Speaker Similarity (SpkrSim): SpeechSSM achieves a score of 0.79, significantly higher than GSLM (0.36) or TWIST (0.41). This validates the strategy of using a separate, speaker-prompted acoustic stage.

- Win Rate: In head-to-head battles, SpeechSSM generally outperforms the baselines.

Long-Form Performance (The Real Test)

This is where the architecture shines. The models were given a 10-second prompt and asked to continue for 4 minutes.

Table 3 paints a clear picture:

- Win Rates: SpeechSSM-2B dominates the field. The column “Win% vs SpeechSSM-2B” shows how often other models beat SpeechSSM. GSLM wins only 17.6% of the time; TWIST wins only 16.2%.

- Naturalness over Time (N-MOS-T): Look at the columns for

<1min,1-2min, etc. Baselines like TWIST degrade rapidly (dropping from 1.96 to 1.36). SpeechSSM maintains a high score (~4.1) throughout the entire 4 minutes. This proves the model isn’t just babbling; it’s maintaining high-quality speech output.

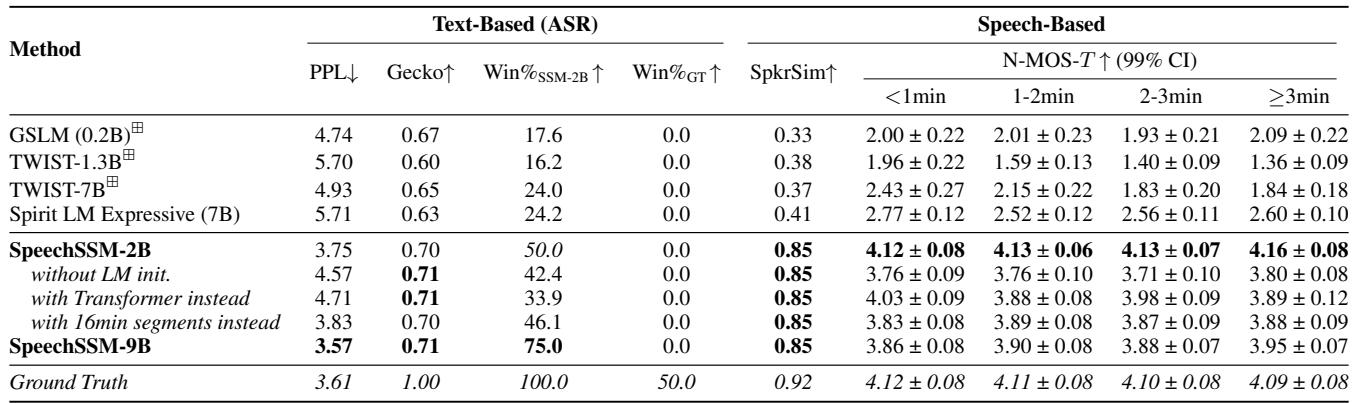

Extrapolation: Going to 16 Minutes

The authors pushed the model even further, generating up to 16 minutes of audio. To quantify “coherence,” they measured the semantic similarity between the generated speech and the original prompt as time went on.

Figure 5 is perhaps the most important chart in the paper. It tracks Semantic Coherence (SC-L) over 16 minutes (represented as distance in words on the X-axis).

- The Black Dashed Line is the Ground Truth (real humans).

- The Blue Lines are SpeechSSM.

- The Gray/Green Lines are the baselines (Transformers, etc.).

Notice how the baselines plummet quickly? They lose the thread of the conversation. SpeechSSM, however, follows a much gentler slope, mirroring the natural topic drift seen in the Ground Truth. It stays coherent far longer than its competitors.

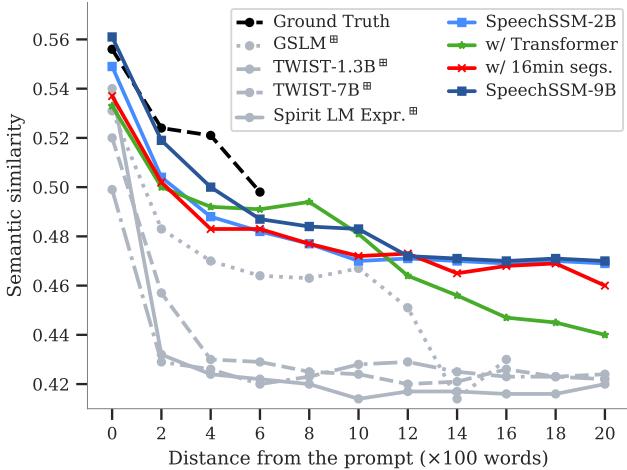

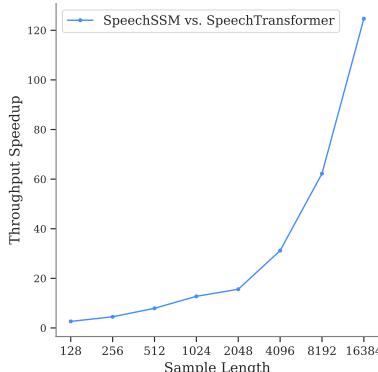

Efficiency

Finally, let’s talk about speed. Because SpeechSSM is an SSM, it should be faster to decode long sequences.

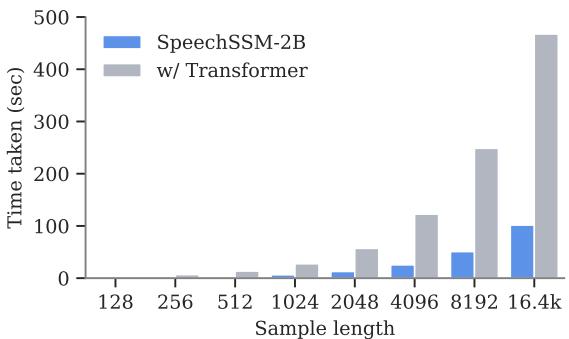

Figure 8 confirms this. The Y-axis shows the throughput speedup of SpeechSSM relative to a Transformer. At short lengths (128 tokens), they are comparable. But as the sequence length grows to 16k tokens (roughly 11 minutes), SpeechSSM becomes over 120 times faster in terms of throughput. This is the difference between real-time generation and waiting hours for a result.

Figure 7 visualizes the decoding time for a single sample. The gray bars (Transformer) grow taller and taller as the sequence gets longer. The blue bars (SpeechSSM) remain low and manageable.

Conclusion & Implications

SpeechSSM represents a significant leap forward in generative audio. By abandoning the Transformer’s quadratic memory costs in favor of the linear efficiency of State-Space Models (specifically the Griffin architecture), the researchers have solved the “memory wall” that prevented long-form speech generation.

Key takeaways:

- Architecture Matters: For long sequences, linear-complexity models like SSMs offer capabilities that Transformers simply cannot match efficiently.

- Divide and Conquer: Separating semantic modeling (the “script”) from acoustic modeling (the “voice”) allows for better coherence and speaker persistence.

- New Benchmarks: We cannot improve what we cannot measure. LibriSpeech-Long and the new LLM-based metrics provide a roadmap for future research in this area.

The implications extend beyond just audiobooks. This technology paves the way for AI voice assistants that can hold hour-long conversations, real-time translation systems that don’t choke on long speeches, and generative media tools that can create entire podcast episodes from a single prompt. SpeechSSM has broken the silence barrier, enabling machines to speak not just in sentences, but in stories.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2412.18603/images/cover.png)