Introduction

For a long time, the prevailing wisdom in Artificial Intelligence was simple: bigger is better. If you wanted a model to solve complex calculus or high-school Olympiad math problems, you needed hundreds of billions of parameters, massive computational resources, and a model like GPT-4 or Claude 3.5. Small Language Models (SLMs), typically in the 1 billion to 8 billion parameter range, were considered efficient assistants for basic tasks but incapable of deep, multi-step reasoning.

That assumption has just been shattered.

A new research paper titled rStar-Math introduces a methodology that allows small language models (specifically 7B parameter models) to not just compete with, but in some cases surpass, the reasoning capabilities of OpenAI’s o1-preview and o1-mini.

The secret lies not in making the model bigger, but in changing how it thinks. By shifting from “System 1” thinking (rapid, intuitive response) to “System 2” deep thinking (deliberate, search-based reasoning), and by employing a clever self-evolution training recipe, the researchers have achieved state-of-the-art results without relying on distillation from superior models.

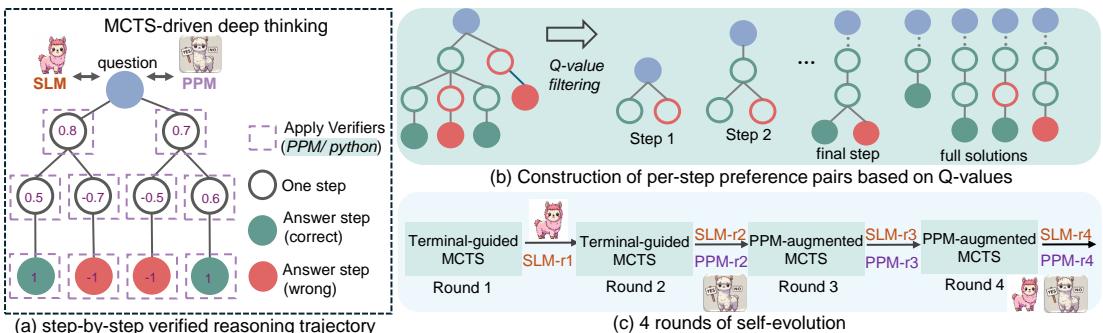

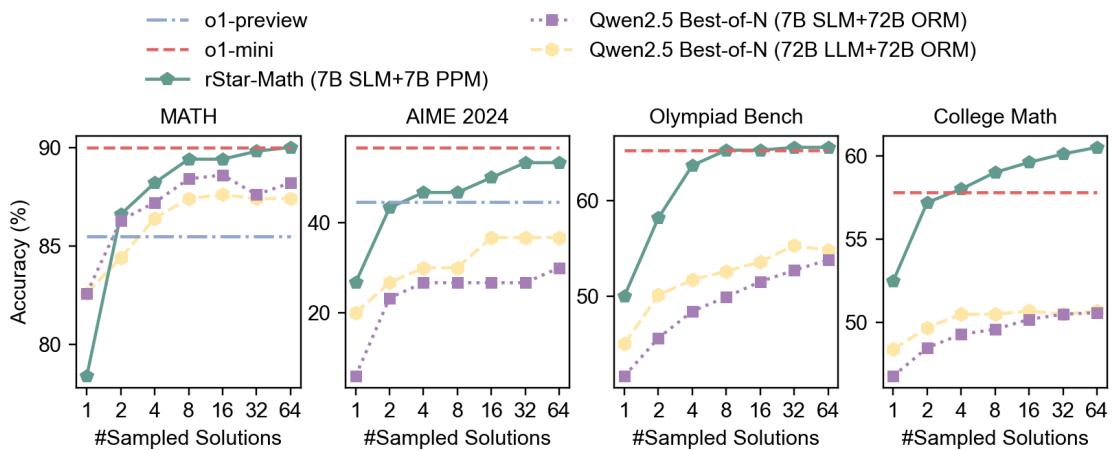

As illustrated in Figure 1, rStar-Math combines Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) with a self-improving reward model to navigate complex math problems. In this post, we will deconstruct how rStar-Math works, why “deep thinking” is the future of AI reasoning, and how a 7B model achieved a 90% score on the MATH benchmark.

The Problem with “Fast” Thinking in Math

To understand why rStar-Math is significant, we first need to understand the limitations of standard Large Language Models (LLMs). Conventional LLMs generate solutions in a single pass, token by token. This is often compared to System 1 thinking in human psychology—fast, automatic, and intuitive.

While this works for writing emails or summarizing text, it is disastrous for mathematics. In a multi-step math problem, a single error in Step 3 renders the entire solution incorrect, regardless of how perfect Steps 4 through 10 are. LLMs are also prone to hallucinations—confidently stating incorrect facts or logic.

To fix this, the industry is shifting toward test-time compute scaling, or System 2 thinking. This involves generating multiple reasoning steps, evaluating them, backtracking if necessary, and searching for the best path to the answer. This requires two components:

- A Policy Model: The AI that generates the reasoning steps.

- A Reward Model: An AI judge that evaluates whether a step is correct or useful.

However, training these components for math is notoriously difficult. High-quality step-by-step math data is scarce. Furthermore, training a reward model to accurately score an intermediate step (e.g., “Is this 3rd line of algebra promising?”) is incredibly hard because a correct final answer doesn’t guarantee the intermediate steps were correct.

The rStar-Math Solution

rStar-Math tackles these challenges with three distinct innovations:

- Code-Augmented CoT Data Synthesis: Using Python code to verify reasoning steps.

- Process Preference Model (PPM): A new way to train the “judge” model that avoids noisy score assignments.

- 4-Round Self-Evolution: A cycle where the model generates its own data to become smarter, which then allows it to generate even better data.

Let’s break these down.

Innovation 1: Code-Augmented Chain-of-Thought

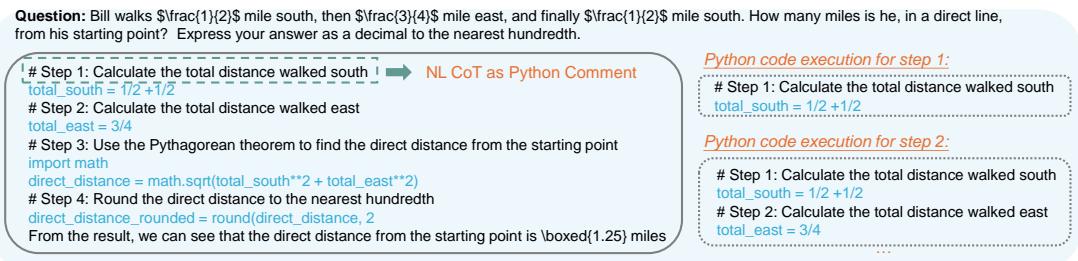

Standard Chain-of-Thought (CoT) relies on the model generating natural language text. The problem is that text is hard to verify automatically. The researchers introduced Code-augmented CoT.

Instead of just writing “I will calculate the distance,” the model generates a reasoning step in text and the corresponding Python code to execute it.

As shown in Figure 2, the reasoning process is broken into nodes. At each step, the model generates Python code. If the code fails to execute, that reasoning path is immediately discarded. This acts as a powerful filter against hallucinations. If the code runs, the output is used to inform the next step. This bridges the gap between the model’s linguistic reasoning and the deterministic nature of mathematics.

Innovation 2: Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS)

To navigate the solution space, rStar-Math employs Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS). Rather than generating one straight line of text, the model explores a tree of possibilities.

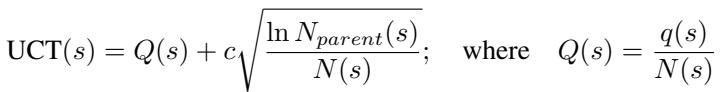

At any given state in the math problem, the model (the Policy SLM) proposes several possible next steps. The system needs to decide which step to explore. It uses the Upper Confidence bounds for Trees (UCT) formula:

Here, \(Q(s)\) represents the estimated quality of the step (provided by the reward model), while the second term encourages exploration of less-visited paths. \(N(s)\) is the number of times the node has been visited.

Rolling Out for Truth

How does the system know if a step is actually good? It performs “rollouts.” It simulates the rest of the solution process from that step onwards multiple times.

- If a step frequently leads to a correct final answer, it gets a high value.

- If it leads to a wrong answer, it gets a low value.

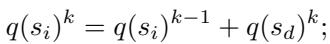

In the early stages of training (Round 1 & 2), the system relies on Terminal-guided annotation. It looks at the final answer (the terminal node) and back-propagates that success or failure to the previous steps:

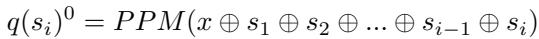

In later stages (Round 3 & 4), once the reward model is trained, it provides an initial estimate for the step quality immediately:

This allows the system to build a dataset of reasoning trajectories where every step has a “Q-value” indicating how likely it is to lead to the correct solution.

Innovation 3: The Process Preference Model (PPM)

Perhaps the most technical but crucial contribution of this paper is how they train the reward model.

Existing approaches try to train a Process Reward Model (PRM) to assign a specific score (e.g., 0.85) to a step. This is called “pointwise” scoring. The problem is that Q-values from MCTS are noisy. A “0.8” might not actually be better than a “0.75” due to randomness in the search. Training a model to regress to these noisy numbers leads to poor performance.

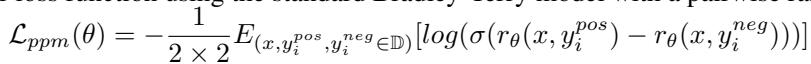

rStar-Math instead trains a Process Preference Model (PPM). Instead of asking “What is the exact score of this step?”, it asks “Is Step A better than Step B?”

They construct “preference pairs” using the MCTS data. They take steps that led to correct answers (Positive) and steps that led to incorrect answers (Negative) and train the model to rank the Positive step higher than the Negative one.

The loss function used is a pairwise ranking loss:

This approach is much more robust to noise. The model learns to distinguish good reasoning from bad reasoning without needing to predict an arbitrary numerical score.

Innovation 4: Self-Evolution

The researchers didn’t just train the model once. They created a self-evolutionary loop.

- Generate Data: Use the current Policy and Reward models to run MCTS on 747k math problems.

- Filter: Keep only the high-quality trajectories (verified by code and correct answers).

- Train: Fine-tune the Policy Model on the successful paths and train a new PPM on the preference pairs.

- Repeat: Use the new, smarter models to solve even harder problems in the next round.

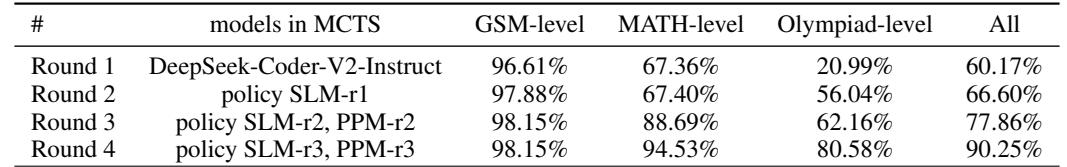

Table 2 shows the power of this evolution. In Round 1, the system could only solve 20.99% of Olympiad-level problems. By Round 4, it could solve 80.58%. The models essentially “bootstrapped” their own intelligence, generating training data that was previously beyond their reach.

Experiments and Results

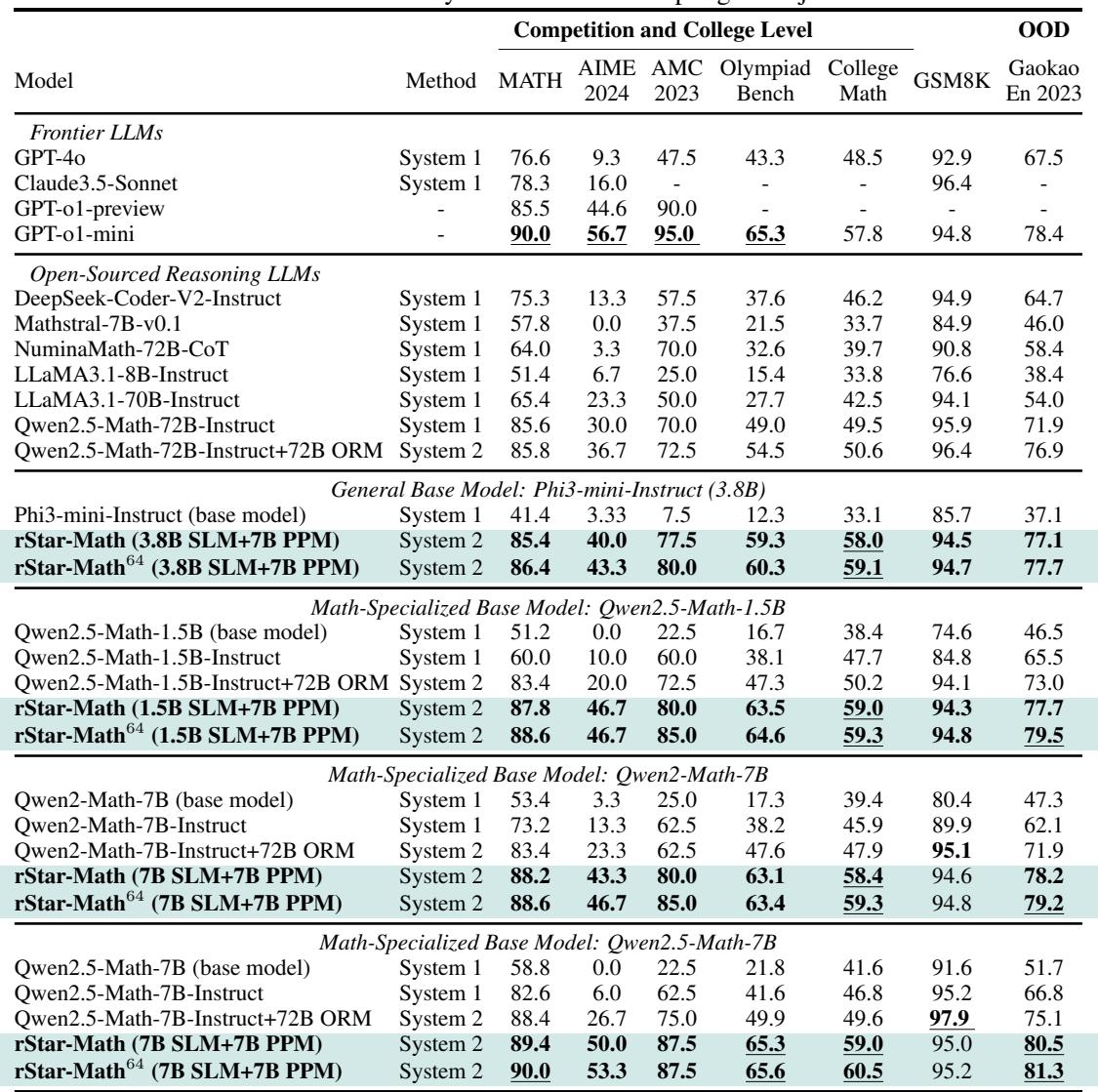

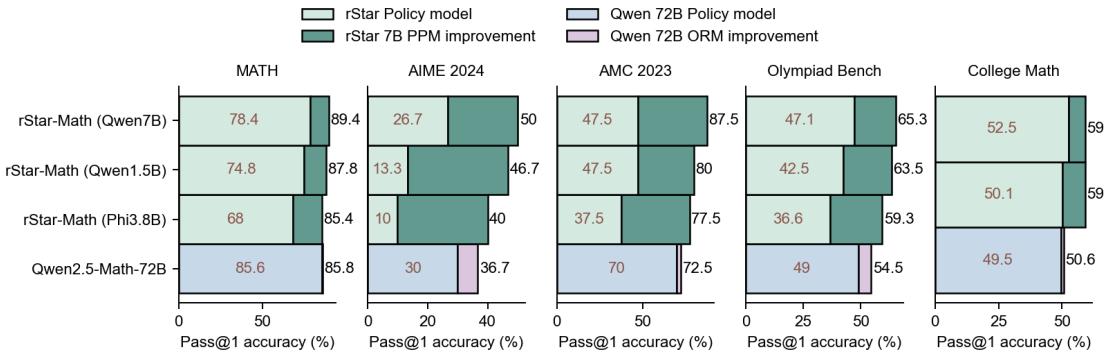

The results of rStar-Math are staggering, particularly considering the model size. The researchers applied this method to Qwen2.5-Math-7B, Phi3-mini (3.8B), and others.

Comparison with Frontier Models

The primary benchmark for math reasoning is the MATH dataset.

- Base Qwen2.5-Math-7B: 58.8%

- rStar-Math (Round 4): 90.0%

This 90% score matches OpenAI o1-mini and outperforms GPT-4o (76.6%) and o1-preview (85.5%).

As shown in Table 5, rStar-Math excels across various difficulty levels. On the AIME 2024 (a qualifying exam for the US Math Olympiad), the 7B model solved an average of 8 out of 15 problems (53.3%), ranking it among the top 20% of high school math students. This is a massive leap over the base model, which scored 0%.

The Power of Test-Time Compute

The paper validates the “System 2” hypothesis: giving the model more time/compute to search yields better results.

Figure 3 illustrates that as the number of sampled solutions increases (from 1 to 64), the accuracy improves. rStar-Math (green line) consistently outperforms standard “Best-of-N” sampling methods (purple line), proving that the MCTS tree search is a far more efficient way to spend computing power than simply asking the model to guess N times.

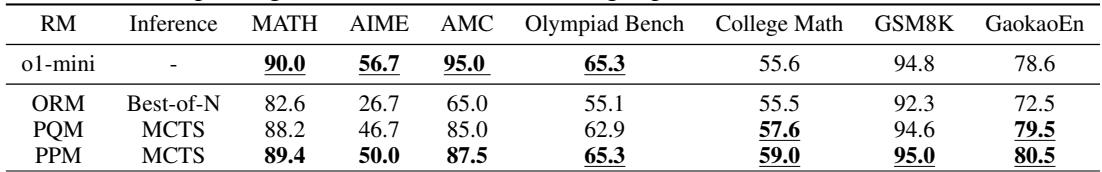

Reward Model Ablation: PPM vs. ORM

Is the new Process Preference Model (PPM) actually better than traditional methods? The researchers compared it against an Outcome Reward Model (ORM) and a standard Q-value PRM (PQM).

Table 8 confirms that the PPM (Process Preference Model) is superior. While ORM (judging only the final answer) improves the base model, PPM pushes the accuracy significantly higher (e.g., 50.0% on AIME vs 26.7% for ORM). This proves that dense, step-by-step feedback is essential for solving complex logic puzzles.

Emergent Capabilities: Self-Reflection

One of the most fascinating findings in the paper is the emergence of intrinsic self-reflection. The researchers did not explicitly train the model to say “Wait, I made a mistake.” Yet, during the MCTS process, the model began to display this behavior.

In Figure 4 (top diagram), we see an example. The model initially tries to solve a problem using a complex algebraic method (the “Low-quality Steps” branch) which leads to a dead end. However, the search process allows the model to abandon that path, backtrack, and try a “brute force” approach checking small integers (the “Intrinsic self-reflection” branch), which leads to the correct answer.

This behavior mimics human problem-solving. We rarely solve hard problems in a single, straight line. We try, fail, realize our mistake, and pivot. rStar-Math enables SLMs to do the same.

Why This Matters

The implications of rStar-Math extend far beyond just homework help.

- Democratization of Intelligence: High-level reasoning is no longer the exclusive domain of massive, closed-source models. A 7B model can be run on consumer hardware (like a high-end GPU or a MacBook Pro), bringing frontier-level math reasoning to local devices.

- Data Synthesis: The biggest bottleneck in AI today is the lack of high-quality training data. rStar-Math proves that SLMs can generate their own high-quality “thinking” data, potentially solving the data shortage.

- Efficiency: Instead of training a 1 trillion parameter model, we can train a small model and use “deep thinking” search at inference time. This allows for adjustable compute costs—spend more time thinking only when the problem is hard.

Conclusion

rStar-Math represents a paradigm shift in how we approach AI reasoning. By combining the linguistic fluency of Language Models with the rigorous search capabilities of MCTS and the verification power of Python code, the researchers have unlocked “System 2” thinking in small models.

Through a 4-round process of self-evolution, these small models have learned to verify their own work, recognize key mathematical theorems, and correct their own mistakes. As the paper demonstrates, size is not the only factor that matters in AI—sometimes, the ability to think deeply is all you need to win.

The era of the “smart” Small Language Model has arrived.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2501.04519/images/cover.png)