1. Introduction

If you have ever watched the movie Inside Out, you are familiar with the concept of “basic emotions.” In the film, a young girl’s mind is controlled by five distinct characters: Joy, Sadness, Anger, Fear, and Disgust. For decades, Artificial Intelligence researchers in the field of Multimodal Emotion Recognition (MER) have operated on a similar premise. They built systems designed to look at a video clip and categorize the human face or voice into one of these fixed, discrete buckets (often adding “Surprise” or “Neutral” to the mix).

But think about the last time you felt a strong emotion. Was it purely “sadness,” or was it a mix of nostalgia, disappointment, and perhaps a bittersweet sense of relief? Human emotion is messy, nuanced, and continuous. It rarely fits neatly into a single box.

This limitation is where traditional AI struggles. By forcing complex human behaviors into closed-set classification tasks, we lose the richness of the human experience. We miss the sarcasm in a smile, the nervous laughter in a tense moment, or the coexistence of surprise and fear.

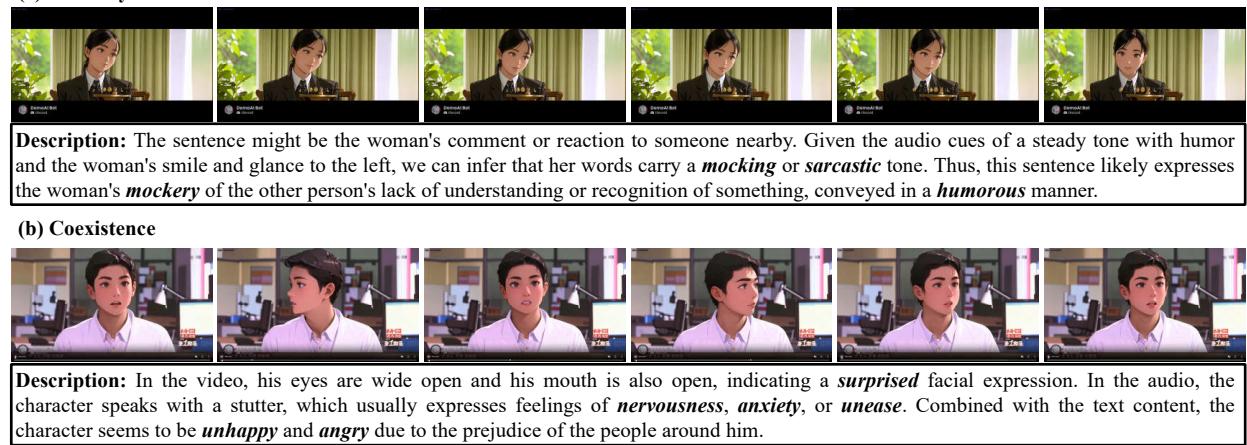

As shown in Figure 1 above, emotions are diverse. In instance (a), a subtle smile combined with a specific tone might indicate mockery rather than happiness. In instance (b), a person can experience surprise, anxiety, and anger simultaneously. To capture this complexity, we need models that don’t just classify but describe.

This brings us to the exciting intersection of Emotion AI and Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs). A new research paper titled “AffectGPT” proposes a comprehensive framework to solve these challenges. The researchers introduce three major contributions that we will unpack in this post:

- MER-Caption: A massive, descriptive emotion dataset.

- AffectGPT: A model architecture designed to better fuse audio and video before the language model processes them.

- MER-UniBench: A unified benchmark for evaluating how well AI understands complex emotions.

2. The Data Bottleneck: Building MER-Caption

The first hurdle in training a generative AI to understand emotions is data. To teach a model to describe emotions in natural language (“The person looks anxious and speaks with a stutter…”), you need thousands of video clips paired with rich textual descriptions.

Existing datasets generally fall into two traps:

- Categorical: They only provide simple labels (e.g.,

label: 1for “Happy”). - Small or Low Quality: Descriptive datasets exist, but they are either too small (because human writing is expensive) or low quality (because they were generated by older AI models without supervision).

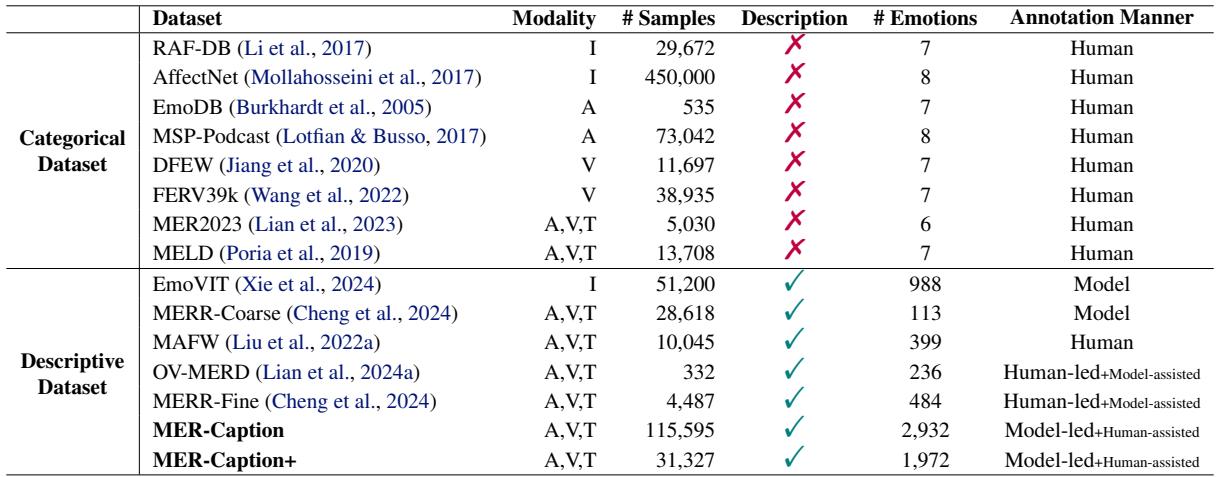

Table 1 below highlights this gap. While categorical datasets like AffectNet have hundreds of thousands of images, descriptive datasets are often much smaller or rely purely on machine generation.

The “Model-led, Human-assisted” Strategy

To solve this, the authors constructed MER-Caption, the largest descriptive emotion dataset to date, containing over 115,000 samples. They achieved this scale without sacrificing quality by inventing a Model-led, Human-assisted annotation strategy.

Instead of asking humans to write descriptions from scratch (expensive) or trusting a model blindly (inaccurate), they used a pipeline that leverages the strengths of both.

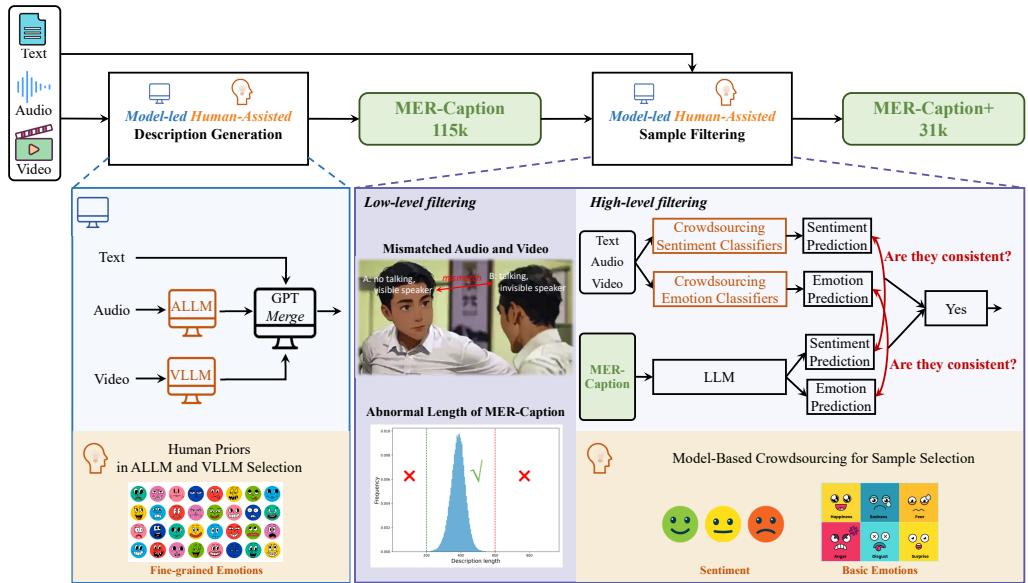

As illustrated in Figure 2, the process involves several clever steps:

- Description Generation: They utilized specialized “Expert” models—an Audio LLM (SALMONN) and a Video LLM (Chat-UniVi)—to extract cues from the raw media. A central LLM (GPT-3.5) then merged these cues with the video subtitles to form a coherent description.

- Low-Level Filtering:

- Active Speaker Detection: Using a tool called TalkNet, they removed videos where the visible person wasn’t actually speaking (a common issue in movie clips where the camera focuses on a listener).

- Length Filtering: They removed descriptions that were statistically too short or too long, as these outliers usually indicate generation errors.

- High-Level Filtering (Model-based Crowdsourcing): This is the most innovative step. They trained several standard emotion classifiers on existing high-quality human datasets. They ran these classifiers on their new data. If the generated description didn’t match the emotion predicted by the classifiers, the sample was discarded. This acted as a “consistency check” to ensure the text description matched the audio-visual reality.

The result is a massive dataset where the machine does the heavy lifting, but human-derived priors (via the trained classifiers) act as the quality control.

3. The Model: AffectGPT

Now that we have the data, how do we build the model?

Most Multimodal LLMs (MLLMs) follow a standard recipe: take a video encoder (like CLIP), an audio encoder, and project their outputs into a Large Language Model (like LLaMA or Qwen). The assumption is that the LLM is smart enough to figure out how the audio and video relate to each other.

However, for emotion recognition, this “late fusion” inside the LLM isn’t always enough. Audio and video often contain conflicting or complementary information that needs to be synchronized before language processing begins.

The researchers propose AffectGPT, which introduces a Pre-fusion Operation.

The Pre-fusion Architecture

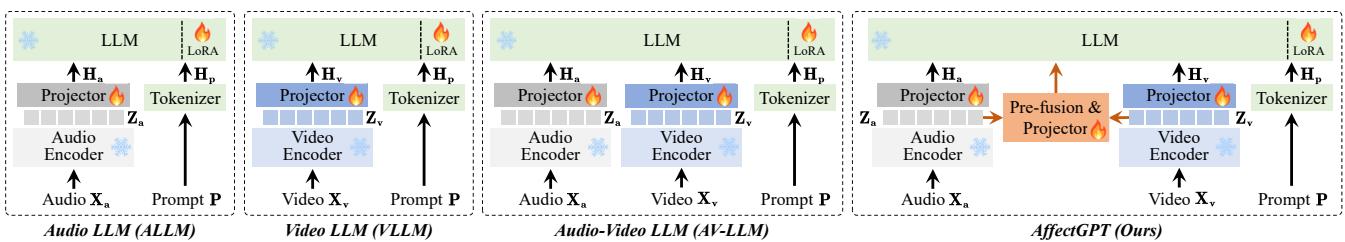

In Figure 3, you can see the difference between standard architectures (like Audio-LLM or AV-LLM) and AffectGPT.

- Standard AV-LLM: The audio features (\(Z_a\)) and video features (\(Z_v\)) are projected separately and fed into the LLM as independent tokens. The LLM has to do the work of correlating a grimace with a scream.

- AffectGPT: The model creates a combined representation (\(Z_{av}\)) explicitly. It fuses the modalities outside the language model.

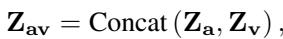

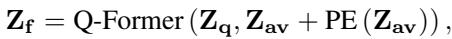

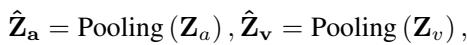

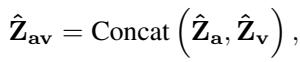

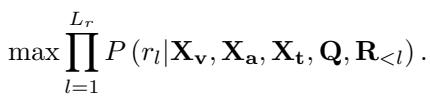

This pre-fusion is achieved mathematically using concatenation and attention mechanisms. The model concatenates the features:

It then processes them. The authors explored two ways to do this: using a Q-Former (a complex query-based transformer) and a simpler Attention mechanism.

Q-Former Approach: This method compresses the visual and audio information into a fixed number of query tokens.

Attention Approach (The Winner): Surprisingly, the simpler attention mechanism often worked better. It involves pooling the features to compress temporal information, then applying a learned weight matrix to fuse them.

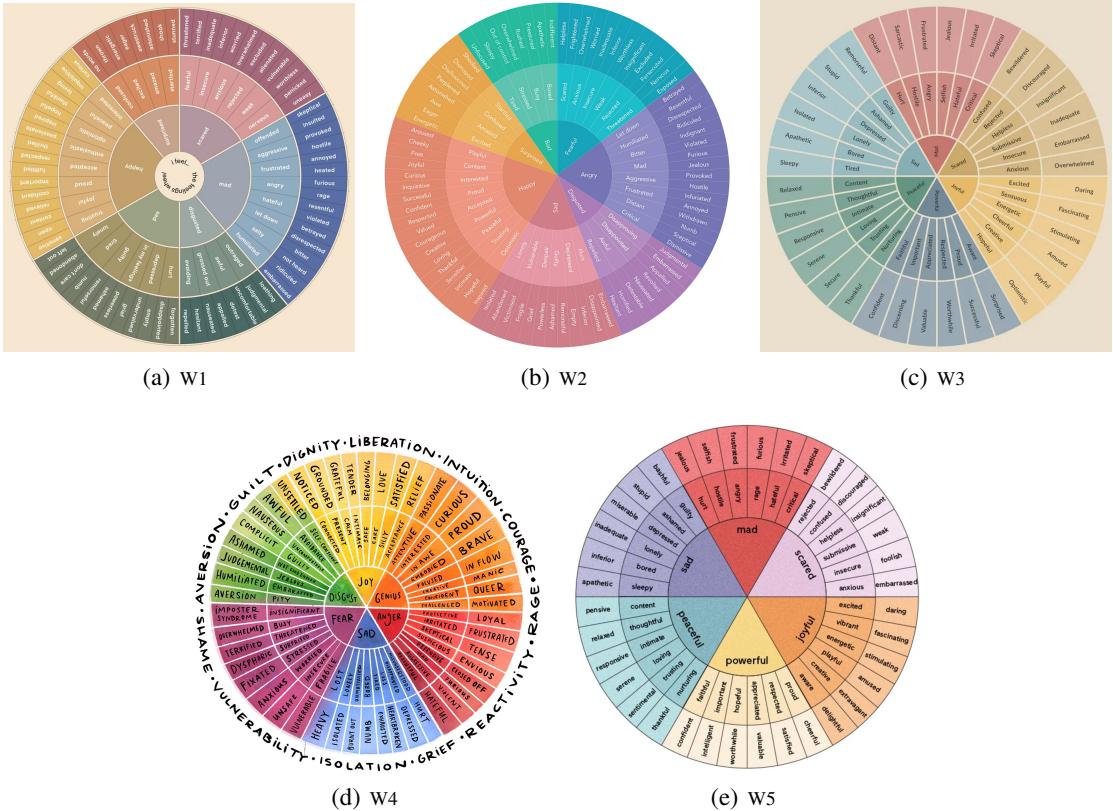

By handing the LLM a pre-fused, synchronized packet of emotional data (\(Z_f\)), the language model can focus on generating the description rather than struggling to align the raw signals. The final objective is standard for LLMs—predicting the next word in the description based on the fused input:

4. How to Grade a Chatbot: MER-UniBench

One of the biggest challenges with Generative AI is evaluation. If a model says “The man looks annoyed” and the ground truth is “The man is angry,” is the model wrong? In a traditional classification task, yes. In the real world, no.

To address this, the authors created MER-UniBench, a benchmark that adapts evaluation metrics to the free-form nature of MLLMs.

Task 1: Fine-Grained Emotion Recognition

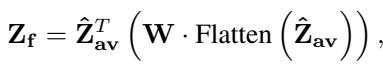

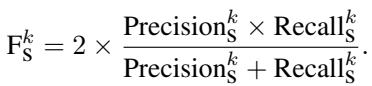

This task evaluates how well the model identifies specific, nuanced emotions. Because different words can mean the same thing (e.g., “joyful” vs. “happy”), the benchmark uses a mapping strategy involving Emotion Wheels.

The system maps predicted words to their base forms (lemmatization), then synonyms, and finally groups them according to sectors on the emotion wheel (as shown in Figure 9).

The metric used is \(F_S\) (Set-level F-score), which balances Precision (did you predict correct emotions?) and Recall (did you find all the emotions present?).

Task 2: Basic Emotion Recognition

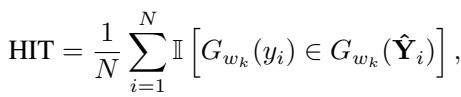

Here, the model must identify standard categories (like Happy, Sad, Neutral). Since the MLLM output is open-ended, the researchers use a HIT rate. If the ground truth label (e.g., “Sadness”) appears anywhere in the model’s generated list of emotions, it counts as a hit.

5. Experiments and Results

Does AffectGPT actually work better than existing models? The results are compelling.

Main Comparison

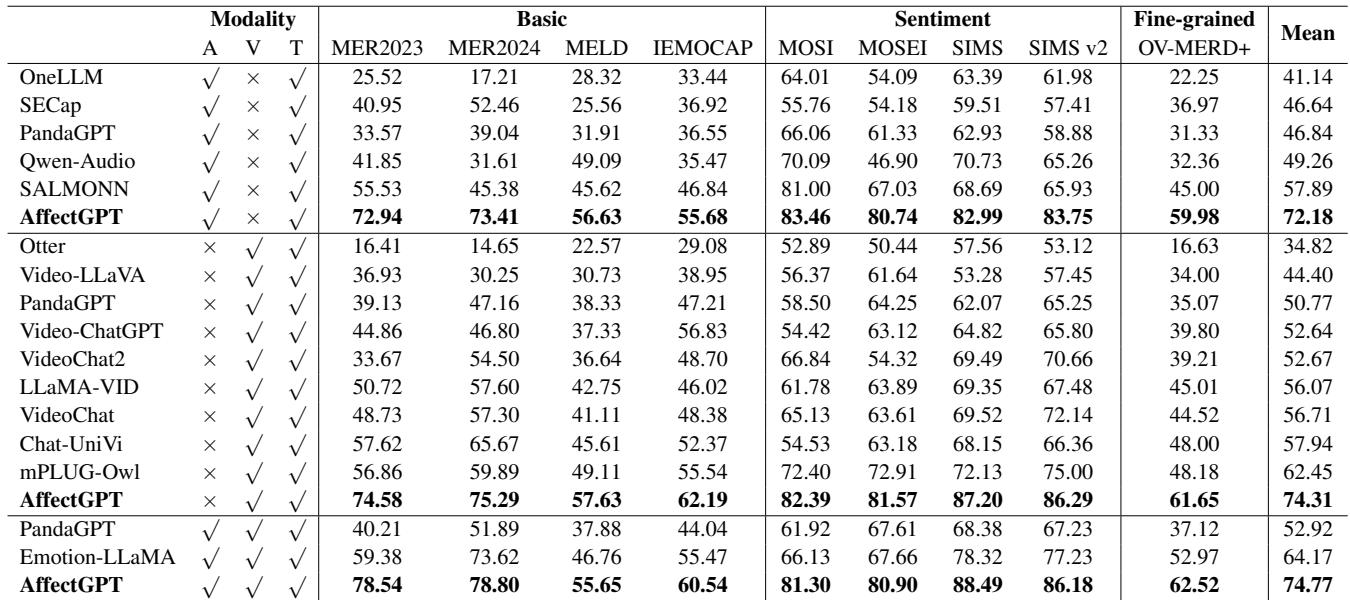

The researchers compared AffectGPT against top-tier MLLMs like Video-LLaVA, PandaGPT, and SALMONN.

As shown in Table 2, AffectGPT achieves the highest scores across almost every dataset.

- MER-UniBench Mean Score: AffectGPT scored 74.77, significantly higher than the next best competitor (Emotion-LLaMA at 64.17).

- Modality Matters: Models that used only Audio or only Video generally performed worse than the multimodal AffectGPT, proving that combining senses is crucial for understanding emotion.

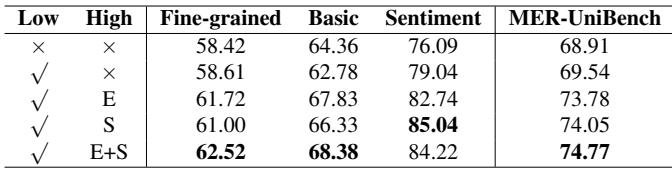

Does the Pre-fusion Help?

The authors performed an ablation study to see if the fancy “Pre-fusion” architecture was actually necessary, or if simply feeding audio and video to the LLM was enough.

Table 5 confirms that pre-fusion improves performance. The “Attention” based pre-fusion (the simpler method discussed earlier) yielded the best results (74.77) compared to no pre-fusion (72.95).

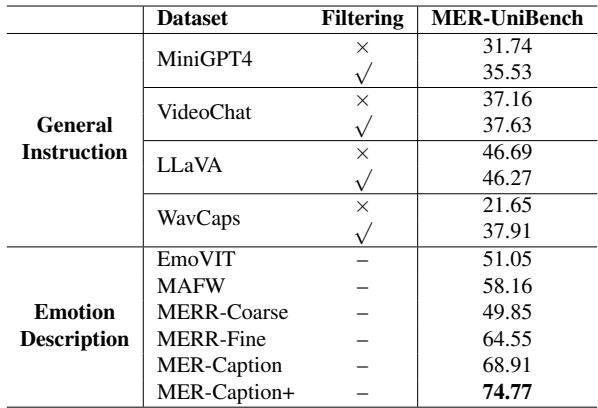

Dataset Impact

Is the new MER-Caption dataset actually better? The researchers trained the exact same model on different datasets to see which one produced the smartest AI.

In Table 3, you can see that training on MER-Caption+ (the filtered version) resulted in a score of 74.77, beating out human-annotated datasets like MAFW (58.16). This validates the “Model-led, Human-assisted” creation strategy.

Qualitative Analysis

Numbers are great, but what does the output actually look like?

Figure 5 shows a comparison.

- Video-LLaVA gives a generic, positive description (“positive emotional state”).

- Video-ChatGPT describes the scene but misses the emotion (“difficult to determine”).

- Chat-UniVi gets closer (“passionate… or nervous”).

- The ground truth implies mockery or sarcasm.

- This highlights that while models are improving, interpreting complex, sarcastic social interactions remains a frontier for AI.

Ablation Studies: Components

Finally, does the choice of the underlying LLM or Encoder matter?

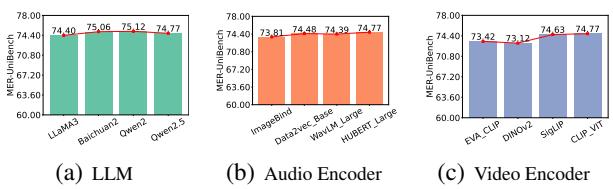

Figure 4 reveals an interesting insight: The performance gains are relatively stable regardless of whether you use LLaMA or Qwen (chart a), or different audio encoders (chart b). This suggests that the AffectGPT architecture and the MER-Caption data are the real drivers of success, not just the raw power of the underlying LLM.

6. Conclusion

The transition from simple classification to generative understanding is a massive leap for Emotion AI. AffectGPT demonstrates that by treating emotion as a complex, multimodal language task rather than a simple sorting task, we can build systems that understand nuance much better.

Key takeaways:

- Data is King: The MER-Caption dataset proves that semi-automated pipelines can generate massive, high-quality training data that outperforms smaller human-labeled sets.

- Architecture Matters: Simply gluing audio and video encoders to an LLM isn’t optimal. Pre-fusing the modalities helps the model synchronize conflicting signals.

- New Benchmarks are Needed: As AI moves toward free-form text generation, we need flexible metrics like MER-UniBench that can handle synonyms and semantic similarity.

This work lays the foundation for more empathetic AI—systems that might one day understand not just what we say, but exactly how we feel when we say it.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2501.16566/images/cover.png)