Deep learning has a fascinating, somewhat counter-intuitive property: if you train two identical neural network architectures on the same data, they will learn to perform the task equally well, yet their internal weights will look completely different.

This phenomenon poses a significant challenge for Model Fusion—the practice of merging multiple trained models into a single, superior model without accessing the original training data. If you simply average the weights of two distinct models (a technique often used in Federated Learning or model ensembling), the result is usually a “broken” model with poor performance. Why? Because the models, while functionally similar, are not aligned in parameter space.

For years, researchers have tried to solve this by exploiting Permutation Symmetry. They reorder (permute) the neurons of one model to match the other. This works well for standard networks like MLPs or CNNs. However, as we will explore in this post, the rigid nature of permutation is insufficient for the complex, high-dimensional geometry of Transformers.

In this detailed breakdown of the paper “Beyond the Permutation Symmetry of Transformers: The Role of Rotation for Model Fusion,” we will explore a groundbreaking approach that moves from discrete permutations to continuous Rotation Symmetry. We will see how rotating matrices within the Attention mechanism allows for a theoretically optimal alignment of Transformer models, leading to significantly better model fusion.

The Symmetry Problem

To understand rotation, we first need to understand the limitations of the current standard: permutation.

Permutation in MLPs

Consider a simple Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP). The network consists of layers of neurons connected by weights. If you swap the positions of two neurons in layer \(l\), and then swap the corresponding incoming weights in layer \(l+1\), the network’s output remains exactly the same.

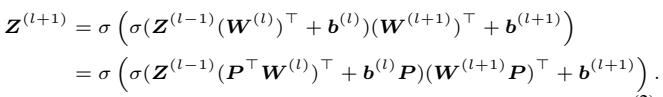

Mathematically, an MLP layer can be described as:

Here, \(\sigma\) is an element-wise activation function (like ReLU). The “Symmetry” here is defined by a Permutation Matrix, \(P\). If we apply a permutation \(P\) to the weights, the function remains unchanged because we can apply the inverse permutation to the next layer.

The key takeaway here is that for MLPs, the “equivalence set”—the set of all weight configurations that produce the exact same function—is defined by these discrete swaps.

The Transformer Challenge

Transformers are built differently. While they contain Feed-Forward Networks (FFNs) that behave like MLPs, their core power comes from Self-Attention Layers.

In an FFN, the element-wise activation function (like ReLU) restricts us. We can only swap neurons because any other linear transformation would get mangled by the non-linear activation.

However, Self-Attention relies on linear matrix products (Query times Key) before the non-linearity (Softmax) is applied. This structural difference opens the door to a much broader class of symmetries. The authors of this paper argue that by limiting ourselves to swapping rows and columns (permutation), we are ignoring the continuous geometric nature of the attention mechanism.

Introducing Rotation Symmetry

The core contribution of this paper is the formalization of Rotation Symmetry for Transformers.

Instead of just swapping indices, what if we could rotate the entire coordinate system of the parameter space?

The Geometry of Attention

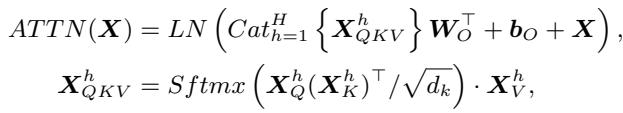

Let’s look at the math of a Self-Attention layer. The attention scores are calculated by multiplying a Query matrix (\(X_Q\)) and a Key matrix (\(X_K\)).

Now, consider a Rotation Matrix \(R\). A rotation matrix is orthogonal, meaning if you multiply it by its transpose, you get the Identity matrix (\(RR^\top = I\)).

The authors realized that we can insert this Identity matrix into the attention equation without changing the result. We can rotate the Queries by \(R\), and “counter-rotate” the Keys by \(R^\top\).

As shown above, the inner product remains identical. The model computes the exact same attention scores, even though the weight matrices \(W_Q\) and \(W_K\) have been transformed.

This same logic applies to the Value (\(V\)) and Output (\(O\)) matrices. We can rotate the Values and counter-rotate the Output projection.

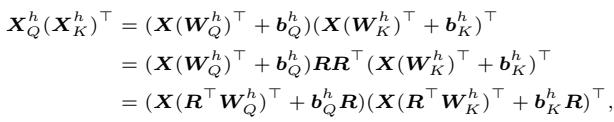

Visualizing the Architecture

This gives us a new set of rules for transforming a Transformer’s weights without altering its function.

As illustrated in Figure 1:

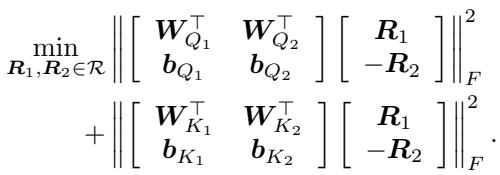

- Q-K Pair: We apply a rotation \(R_{qk}^\top\) to the Query weights and the Key weights. Because one is transposed in the attention operation, they cancel out.

- V-O Pair: We apply a rotation \(R_{vo}^\top\) to the Value weights and apply \(R_{vo}\) to the Output weights.

This discovery is significant because rotation operates in a continuous space. Unlike permutation, which is discrete (you either swap neuron 1 and 2, or you don’t), rotation allows for smooth, infinite adjustments to the alignment of the model parameters.

Algorithm: Optimal Parameter Matching

Why does this matter? It matters because of Model Fusion.

When we want to merge two models (let’s call them Model A and Model B), we usually perform a weighted average of their parameters. However, neural network loss landscapes are non-convex. Even if Model A and Model B are both at low-loss solutions, the “straight line” average between them often passes through a region of high loss (a “loss barrier”).

We need to match (align) Model A to Model B before averaging. We want to find the rotation \(R\) that makes Model A’s weights as mathematically close to Model B’s weights as possible, without changing Model A’s actual predictions.

The Intuition

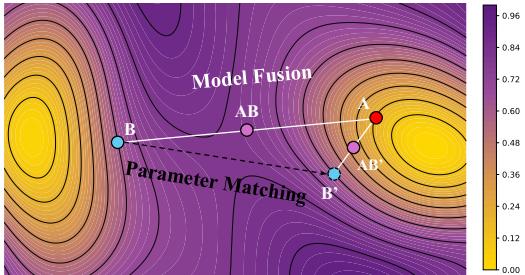

Figure 2 provides a beautiful visualization of this concept using a loss landscape contour map.

- A and B are our original models.

- AB represents the naive merger. It lands in a high-loss (yellow/green) area.

- AB’ represents the merger after Parameter Matching. By rotating Model A to align with Model B, the merged model lands in a deep, low-loss basin (purple).

The Math of Matching

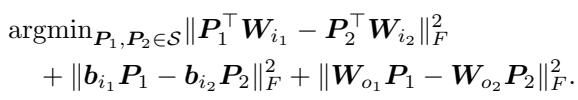

The authors formulate this alignment as an optimization problem. For the Feed-Forward Networks (FFNs), they still use permutation matching because of the ReLU activation.

However, for the Attention layers, they use the new Rotation Symmetry. The goal is to minimize the Euclidean distance (Frobenius norm) between the weights of the Source Model (1) and the Anchor Model (2).

This looks like a complex regression problem, but because \(R\) is constrained to be an orthogonal rotation matrix, this falls into a known class of problems called the Orthogonal Procrustes Problem.

The Closed-Form Solution

Remarkably, we don’t need gradient descent to find the best rotation. The authors provide a theorem showing there is a closed-form solution using Singular Value Decomposition (SVD).

The optimal rotation \(R\) is simply \(UV^\top\), where \(U\) and \(V\) come from the SVD of the product of the weight matrices. This makes the matching algorithm computationally efficient and numerically stable.

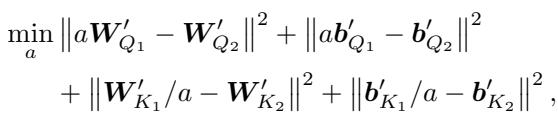

Adding Rescaling

The authors go one step further. Beyond rotation, neural networks also exhibit Rescaling Symmetry (e.g., multiplying weights by \(\alpha\) and dividing the next layer by \(\alpha\)). They integrate this into their algorithm, solving for a scalar \(a\) that further minimizes the distance.

Experimental Results

The theory is sound, but does it work in practice? The authors tested their Rotation-based Matching algorithm across various domains.

Natural Language Processing (NLP)

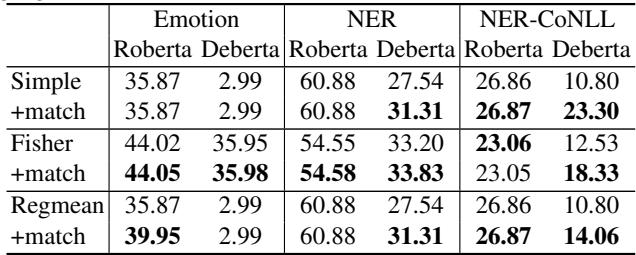

They fine-tuned RoBERTa and DeBERTa models on emotion classification and Named Entity Recognition (NER) tasks. They then merged pairs of models using three different fusion techniques:

- Simple: Direct averaging.

- Fisher: Weighted averaging based on Fisher information.

- RegMean: Regression-based merging.

In all cases, they compared the baseline fusion against fusion + matching (Ours).

Key Takeaways from Table 1:

- Consistent Gains: The

+matchrows almost universally outperform the baselines. - Significant Improvement for Simple Fusion: Look at the DeBERTa / Emotion column. Simple fusion completely failed (Accuracy: 2.99), likely because the models were misaligned. With matching, it jumped back to useful performance.

- State-of-the-Art: Even for advanced methods like RegMean, adding rotation matching squeezes out extra performance.

Computer Vision

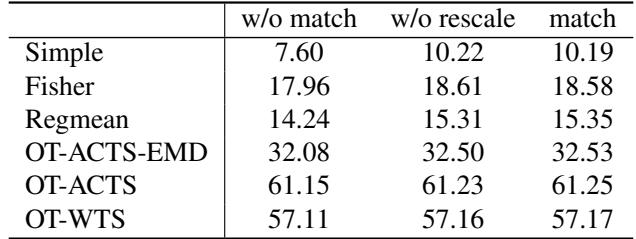

They also tested Vision Transformers (ViT) on image classification (CIFAR-10). They compared their rotation method against optimal transport (OT) baselines.

The results in Table 2 reinforce the NLP findings. The rotation-based matching (rightmost column) consistently yields the highest accuracy.

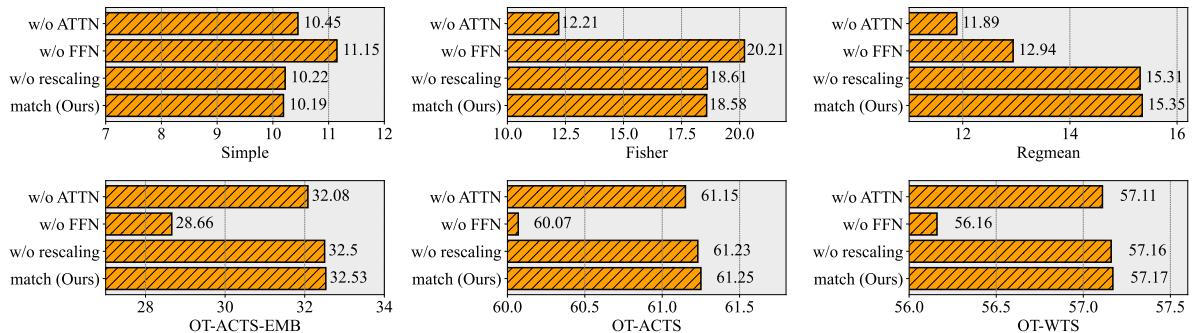

Ablation Study: What matters most?

Is it the rotation in the Attention layers or the permutation in the FFNs that contributes most to the success?

Figure 3 reveals an interesting nuance.

- For Fisher and RegMean merging, removing Attention matching (

w/o ATTN, purple bar) causes a significant drop in performance. This proves that aligning the continuous attention space is critical for these advanced merging methods. - For OT-Fusion, the FFN matching seems more dominant, but our full method (orange bar) is still the best or tied for best across the board.

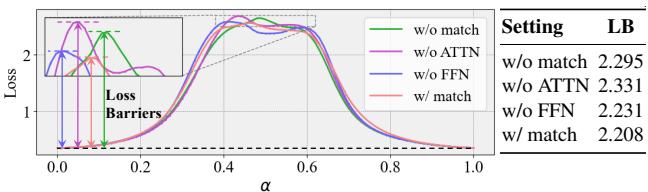

The Loss Barrier

To physically prove that the models are “closer” in the optimization landscape, the authors plotted the loss along the path between Model A and Model B.

In Figure 5, the green line (no matching) shows a huge spike in loss (the “barrier”) when moving between models. The red line (Match) is nearly flat. This “Linear Mode Connectivity” is the holy grail of model fusion—it implies the two models effectively reside in the same convex basin of the loss landscape.

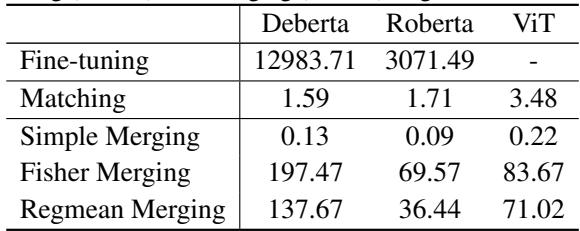

Computational Complexity

One might worry that performing SVD for every layer is slow.

Table 3 puts those fears to rest. The matching process takes roughly 1.5 to 3.5 seconds—a negligible amount of time compared to the hours spent fine-tuning the models. It is a highly efficient “plug-and-play” module.

Discussion: Efficiency and Depth

The authors investigated one final question: Do we need to match every layer?

They experimented with matching only specific subsets of layers in a 24-layer DeBERTa model.

Figure 6(a) shows the impact of matching a single layer. Interestingly, matching the earlier layers (indices 0-5) reduces loss much more than matching the later layers.

Figure 6(b) confirms this trend. The curve “Tail-Layers Matching” shows that matching the last few layers provides very little benefit. The drop in loss (improvement) only accelerates when the early layers (the “Head” layers) are included. This suggests that the early layers of Transformers diverge more significantly during training and require the most alignment.

Conclusion

This research marks a significant step forward in our understanding of Transformer geometry. By identifying Rotation Symmetry as a continuous generalization of permutation symmetry, the authors unlocked a more powerful way to align models.

Key Takeaways:

- Transformers are continuous: Restricting alignment to discrete permutations ignores the geometric nature of Self-Attention matrices.

- Rotation is optimal: We can solve for the best alignment using a closed-form solution (Procrustes/SVD) rather than approximating with discrete solvers.

- Better Fusion: Aligning models via rotation drastically reduces the loss barrier between them, allowing for successful merging where naive methods fail.

- Efficiency: The algorithm is fast, scalable, and works as a plug-and-play enhancement for existing fusion techniques.

As we move toward a future of decentralized AI and Federated Learning, techniques like this—which allow us to stitch together disparate models into a cohesive whole—will become increasingly vital.

The full code for this paper is available at https://github.com/zhengzaiyi/RotationSymmetry.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2502.00264/images/cover.png)